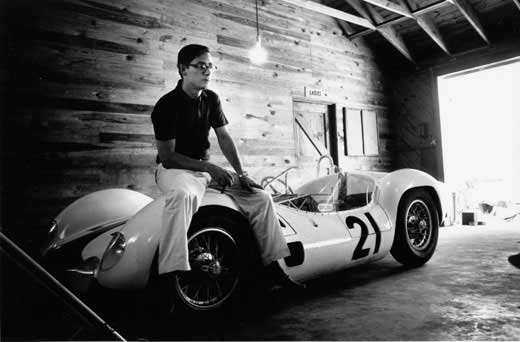

Masten Gregory contemplates driving for Camoradi USA. Flip Schulke photo.

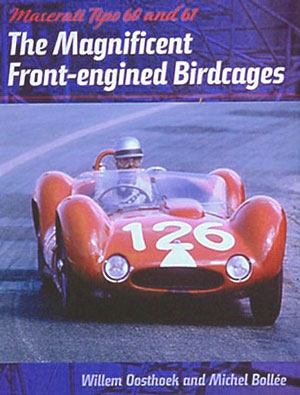

Maserati Tipo 60 and 61 The Magnificent Front-engined Birdcages

By Willem Oosthoek and Michel Bollee

Hard cover with slipcase, 335 pages of color and black and white photos. Published by Dalton Watson, Deerfield IL

ISBN 978-1 85443 238-4

Review by Pete Vack

Thanks to Willem Oosthoek, Michel Bollee and several others, we are gathering an impressive library of well-researched books on Maserati which in due course may approach the level of research done on other marques, such as Ferrari. Previously, writers such as Joel Finn, Rob Box, Anthony Pritchard and Orsini/Zagari have laid the groundwork with overall histories and technical specs for many of the pre and post-war Maseratis. Since 2000, a more detailed series of books have been published, all with serial number information. To that list, this year we can add “The Magnificent Front-engined Birdcages” again by Oosthoek and Bollee, which delightfully covers the twenty two Maserati Tipos 60 and 61.

Although the Tipo 63-65 and 151 sports racers would follow the Birdcage, none would have the international success accorded to the front engined three liter Tipo 61. In fact, after thirty five years of producing winning race cars, the Birdcage was effectively the last successful racing car to be produced by the Maserati works in Modena.

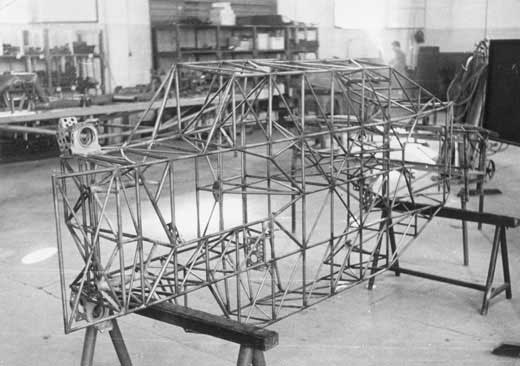

200 large and small tubes made up the complex Birdcage chassis.

As the low slung and controversial body might suggest, the Tipo 60 (2 liter four) and 61 (2.9 liter four) constituted a full measure of change particularly in the chassis department which, since the Maserati brothers, had been always strong and heavy. Ing. Giulio Alfieri decided to throw that bit of the past away to replace the heavy ladder frame and create a tubular chassis consisting of 200 small and large tubes. To prove its strength to Lucky Casner, Alfieri took a sledgehammer to a bare chassis. Hardly a good test, and another story is that the boys at Maserati would send Moss out in the prototype to twist the chassis until the pipes broke, and the offending tubes were replaced by a softer low grade steel. But even that didn’t solve the problem as throughout the 1960 SCCA season, Gaston Andrey’s mechanic would go in search for broken tubes in s/n 61.2455 whenever the chassis started getting squirrelly. (Read Track Test, Maserati Birdcage).

Bertocchi, at left. Rouen, 1959 and the prototype s/n 60.2451. It won first time out.

Saving the de Dion from the 200SI to be levered into the rear of the Birdcage, Alfieri used the front suspension from the last of the “Piccolo” 250Fs and installed the latest Girling discs brakes all around. The tried and true four cylinder 2.9 liter 250 hp DOHC Maserati, now somewhat cured of chronic oil leaks, was canted 45 degrees to further lower the profile. Hammer out a marginal body over the cage and you have a world class race car. This then, is the magnificent and unforgettable racecar defined in detail by the latest Oosthoek/Bollee effort.

Like its full title, “Maserati Tipo 60 and 61, The Magnificent Front-engined Birdcages”, is hefty, at 9 ¾ by 13 ¼ inches and 335 pages of large color and black and white photos, published by Dalton Watson, printed in their elegant fashion with 150 gsm Multiart silk, complete with slipcase. Like all DW products, this is a quality book and yes, at $150 is a bargain.

Indexing is refreshingly well done. Each year from 1959 to 1967 has a ‘Schedule of results’ table including chassis numbers at each event. Each car has a table with its competition history, and post competition history as well. At the back of the book there is a compilation of the drivers of the Tipo 60 and 61 listing the years and chassis numbers next to the driver. Neat. Then, an Index of Chassis Numbers. Find the chassis of choice, and this index will let you know on what pages text and photos can be found. In addition, the authors have made a chart which indicates which results table has a mention of the s/n. Next, a full index of proper names. These are assets that make life easy for historians, editors, fact checkers and Internet busybodies. They also make the book a much used reference despite its bulky size.

There are no footnotes of any type in the book, but a full page of sources lists the books, magazines and newspapers used for research. Interviews– and there are many–are quoted in the book with references to the interviewee but without dates and places. It makes for easier reading but we do miss the precise information, or when and where did the interview take place and who actually did the interview. This lacking does not mean to imply that any of the information is not valid or vetted–on the contrary, both authors are sticklers for accuracy. Knockers still got by them, one being the tech specs sheet which described the de Dion as using transverse springs with coil springs.

Targa Florio, 1962, s/n 60.2466 driven by the Riolo brothers.

The book itself is very well organized. Part 1 reveals the ‘Origin of the Birdcage design’, Part 2 is the ‘Competition history year by year’, Part 3 is the ‘Competition and post competition history by chassis‘, Part 4, ‘The drivers of the Maserati Tipo 60 and 61’. It could well have been titled “The Life and Times of the Maserati Birdcages”, for the book covers much more than just the Birdcages themselves.

Oosthoek looks at the US racing scene between 1959 and 1967 in detail, providing not only a racing history of the Maserati, but a more general history of this important and fast moving era of racing. It’s tough, too, as the authors have to explain and shift between SCCA racing to Cal Club to USAC and the USRRC events which were throughout the U.S., plus the explanations of the various classes. This is in addition to covering the World Sports Car Championship (WSCC) with events in both the U.S. and Europe. To their credit, the authors address every event entered by every one of the Birdcage Maseratis built.

As any Maserati enthusiast knows, Camoradi USA was posed to represent the U.S. in the World Sports Car Championship and was very instrumental in the success of the Tipo 61 Birdcage Maserati. The full story was previously published in France by co-author Michel Bollee but is here in English. Camoradi USA–stood for Casner Motor Racing Division, virtually unknown until two back-to-back victories at the Nurburgring put the team on the map. How Lloyd Casner went from a Miami used car dealer to team owner and race driver hobnobbing with Brigit Bardot is told with the help of Fred Gamble, mechanic Lee Lilly and his son Perry. Never before published photos of the team, with Moss, Gregory and Shelby, capture the mood of the era.

Glory days: Casner, left, BB in the center and Masten Gregory.

Camoradi USA would eventually purchase five Tipo 61s. Armed with this stable and sponsorship money, Casner was able to hire Moss (at a reported $5000 per race), Gregory, Gurney, and Shelby (with whom Casner had a serious falling out) and others. The Casner story is told in full with many new photos.

Even quicker to see the charms of the new Birdcage was a Caterpillar parts dealer from L.A., Joe Lubin and his driver Bob Drake. Movie theater owner E.D. Martin also was among the first to get a new Tipo 61, destroying it in a horrific crash at Daytona and ending his career. Birdcages also were owned or raced by Jim Jeffords, Bill Krause, (who also wrote the Introduction) the Cunningham team, Roger Penske and Jim Hall, to name a few, and each one is covered in-depth.

Photography in the book is also incredible, and here the help came from Jack Brady, Bernard Cahier, Bob Jackson, Jim LaTourrette, Flip Schulke and Bob Tronolone among others. Oosthoek found many willing to share their family albums, allowing the photos to be published without cost. Nevertheless, the authors spent about $4,000 on copyrighted images used in the book–the right thing to do and the results show it.

DARN YOU VELOCE TODAY! another great book i cant afford. oh well, back to the plasma bank…