Wacker with the Burrell-prepared Allard at Watkins Glen. Frank Burrell is standing behind Wacker's right shoulder.

By Eric Davison

All photo courtesy of Barry Burrell and the Allard Register

Eric Davison, who originally hails from the Detroit area, witnessed the birth of sports car racing from a unique perspective; his father was an early SCCA member who traveled to Watkins Glen every year with his son, driving exciting cars like the drop dead gorgeous British Squire. Davison has not only written a series of eight chapters on those years for VeloceToday, but continually brings us new and interesting stories about the pioneers of the sports car movement.

While we are all familiar with the use of Cadillac engines in the Cunningham cars at Le Mans, the famous Cad Allards and the Frick Vignales, little is known of Cadillac’s behind the scenes involvement with the sport, encouraged by the team of Ed Cole, Harry Barr and the subject of this article, Frank Burrell. With the help of Frank’s son Barry, Davison traces the little-known involvement of GM’s Cadillac division which was looking for ways to bring the excitement of speed to their flagship luxury car. [Ed.]

It is interesting to see that Cadillac is now touting the performance capabilities of their new BMW fighter. Performance in a luxury car is nothing new; Mercedes with their AMG offerings, the BMW ‘Ms” and certainly most of what Audi does, is performance-related. Performance is an important part of a car’s image. While it appears that Cadillac is new to the party, the fact is they are not. They were first into the post war performance race but they quickly abandoned their foothold in order to place their emphasis on creating the biggest and most bloated cars that the planet had ever seen.

Their foothold into the performance market was almost entirely created by one man: Frank Burrell, and lasted only a few years.

While Frank Burrell is most likely known best and appreciated more by Allard lovers, Frank’s contributions to motor sports covered a wide range of activities from hot rodding to Le Mans. In terms of automobile performance, he was a true renaissance man. He was active in and made serious contributions to just about every venue in motor racing; from circle track to drag racing to sports cars, to racing at Watkins Glen, Sebring and Le Mans.

Frank was an engineer and a true car guy and he led the way for Cadillac’s early lead into the post war performance market.

Frank Burrell was born in LaSalle, Illinois in 1915. His father had been a successful construction engineer and the family lived comfortably. A Duesenberg was the family transportation.

Like so many American families, the Burrell family fortunes took a decided downturn during the depression and the family was forced to relocate to rural Wisconsin in 1930.

Frank had always been an inveterate tinkerer and, like many boys had created his own motorized car when he was 14, an early start on an automotive career.

Being an engineer was his goal and he entered the Engineering School at the University of Wisconsin; helping to finance his education with a part time job in a salvage yard. This led to his being able to gather enough components to create race cars based on Model T components. For a couple of years he was a successful competitor with his Model T specials.

In 1938 Frank received a degree in Engineering from the University of Wisconsin. In 1939 he married the lovely Marjorie Day and in 1942 they were off to Detroit where he had been hired by the Cadillac Division of GM.

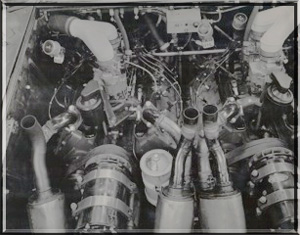

No cars were being produced during those war years and his assignment was to add some speed and maneuverability to the M5A1 (Chaffee) tank that Cadillac was producing for the Army. The Chaffee utilized two pre-war Cadillac V8s and an adaptation of GM’s Hydra-Matic transmission. Performance was enhanced when the Chaffee was fitted with the Burrell-designed dual carburetor manifold fitted to each V8.

With the war’s end, Frank Burrell joined the engineering team that was headed by Ed Cole and included Harry Barr. This was the team that created the Cadillac overhead valve V8, the first modern engine to come out of post-war Detroit. (They next moved to Chevrolet and were responsible for the incredibly successful small block Chevy.)

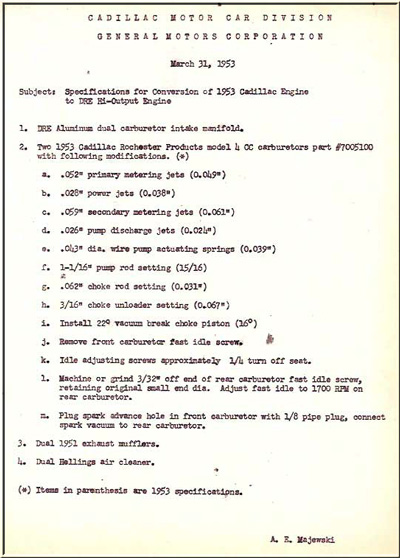

At the same time Frank obtained the tooling for the tank intake manifold and began to sell performance kits for the post-war Cadillac flat-head V8.

Cadillac’s new high-output and relatively lightweight V8 drew a lot of attention from performance addicts including Briggs Cunningham who had entered the 1950 LeMans 24-hour race with two Cadillacs; a Series 62 Sedan and the famed Le Monstre, an aerodynamic but incredibly ugly vehicle. The sedan used a two-carb manifold and the Le Monstre utilized a five-carb set up also designed by Frank. The two-carb set up was one that Cadillac was testing for production.

There were also internal engine parts that were created; forged pistons, heavy duty bearings, oil seals, etc. that were needed to enable the Cadillac engine to hold up for the 24-hour grind.

The obvious need for the Cunningham team was to include Frank Burrell as technician and overseer of the Cadillacs. The sedan finished 10th overall and Le Monstre, 11th. Frank came home having made friends of Sydney Allard and Zora Arkus-Duntov. At that time Duntov was working for Allard.

The new engine inspired a number of sports car racers to try Cadillac power. Foremost among them was Fred Wacker, a prominent SCCA racer who had purchased a J2 Allard. Wacker and Burrell were both SCCA members and friends who knew each other from SCCA activities.

When Wacker purchased his J2 Allard, he sent the car to Burrell, who along with the heavy duty performance parts that he had created for Le Mans, installed his two-carburetor manifold and an adaptation of the Hydra-Matic transmission that had been used in the Chaffee tank. Wacker entered the car in the 1950 running of the Watkins Glen grand Prix and finished third behind two other Cadillac-powered cars; that of Irwin Goldschmidt in a J2 Allard and Briggs Cunningham in his Healey Silverstone with Caddy power. While Goldschmidt didn’t run the Hydra-Matic he was the beneficiary of Frank Burrell’s expertise and the high performance parts that he had created for Cadillac.

Frank sits next to Cal Connell of Detroit Racing Equipment in Goldschmidt's Allard. Burrell's engine modifications made the Goldschmidt Allard very potent. Click on the photo to read more about Goldschmidt.

In January (1950) Frank teamed with Wacker to compete in the first six-hour event at Sebring. While the car covered two more laps than the second place car, the Wacker/Burrell entry finished eighth overall. At the time Sebring ran under FIA rules that determined the winner by a complicated index of performance formula. The utilization of this formula allowed a Crosley Hotshot to be the overall winner. (It also gave the predominantly small French cars an edge at Le Mans.)

Wacker also took that car to Argentina for a race. After the race he sold the car to a local enthusiast. For some inexplicable reason, Eva Peron herself killed the deal and the car returned to the US and was sold on these shores. By then Wacker had already ordered his next J2, the famed (or ill-fated) ‘Eight Ball.’

At this point another GM employee became involved in sports car racing. Fred Warner, an ex-military pilot, found peace-time employment with the General Motors Air Transport Service. GMATS purpose was to fly GM people and parts to the farthest points of the GM empire. Like a good many pilots he had a craving for speed and purchased a J2X Allard.

Warner was obviously a top-ranked pilot because his primary passenger was C. E Wilson, GM board chairman, later to become Secretary of Defense in the Eisenhower cabinet. He also piloted Harry Klingler, the vice president of the Pontiac Division. From Wilson he gained access to Burrell and the Cadillac performance group who developed an engine for his J2X Allard. From Klingler he gained a wife; he married his daughter, the lovely Sis.

Warner’s car served as a test bed for numerous modifications from both Cadillac and the aftermarket that were being tested by Cadillac engineers.

Next: Frank Burrell and General Curtis LeMay

There is no doubt in my mind Frank Burrell was the person who gave assistance

, thru the ” back door” to Briggs Cunningham. Further, it is likely when this was discovered, Briggs had to turn to Chrysler for powerplants, (his own personal road car was 1949 fastback with the fins REMOVED..ala California Kustom. Burrell’s own Cadillac convertible was fitted with Borrani wire wheels! (photo of car and other personal data on Frank can be found in ROAD & TRACK for Feb & Sept 1952

Jim Sitz

G,P, Oregon

Of all the great and informative VT writers, for me, I find Eric’s the most interesting. If Eric is reading this, I would very much appreciate any information on the Detroit Racing Equipment (DRE) Company. Was Burrell a principal in the company? How long did they exist, what products besides manifolds did they produce, etc.?

I use various Edmunds intakes, both 2 x 2 and 4 x 4’s on the early 331 engines, but have never had a DRE. It would be interesting to compare the two.

Eric, your describing the LeMans entry as a “sedan” rather than a Coupe de Ville is most interesting, because I’ve always thought that Cunningham got a way with a hybrid at LeMans in 1950.

If you look closely at pictures the entry appears in every way to be the short WB series 61 and not the much heavier, long WB series 62 ONLY Coupe de Ville. The lack of trim, etc. is that of the 61, only thing is the Coupe de Ville was only available as a Series 62! The series 61 two door was only available in the traditional Club Coupe, sometimes called a post coupe. It had a 122″ WB as opposed to the 126″ of the Series 62. It was much lighter and stiffer than the Series 62.

Seems to me that Cadillac built a one off series 61 CdV just for Lemans. Saving about 250 pounds and adding an additional French namesake at the same time. Surely, the French would look the other way, if indeed they even knew. How could they refuse a Cadillac, much less one named Coupe de Ville?

As we know, it paid off handsomely with a 10th place finish. And probably sold a few CdV’s to wealthy Frenchman in the process.

Can you add anything to my speculation?

Thanks for the great historical articles and personal insight.

Denton

Opps! Sorry, the series 61 was available in the hardtop in 1950, but not in a CdV style. 1949 being the last post coupe (in a Sedanatte). Some 11,839 pillarlesss coupes being built in 1950. So French didn’t have to turn their back!

Congratulations Eric. A super article. Interesting and informative.

I believe Frank Burrell also had something to do with designing either an early or an improved version of the colostomy bag. Perhaps another reader could elaborate on this.

You have to love VeloceToday for providing background stories like this that are not available elsewhere. Thank you Pete and your incredible stable of authors. I’m proud to be among you.

The following comment is from Richard Irish, who participated in many of the early sports car races throughout the U.S.

Hi Pete,

The Burrell / Allard piece brought back MANY memories! As you may recall, I was with the Corvette team at Sebring in 1956 (only to get shafted out of a ride by John Fitch) I think Max Goldman and I were the ONLY guys not getting paid, some “under the table”. I had met Frank back in the Art Bly, Wacker period. Driver assignments had not been finalized and we were all busy as beavers still building the cars in the week leading up to the race. Anyway, Briggs Cunningham asked if I would partner Bill Lloyd in his O.S.C.A., and I replied that I’d have to get “clearance” from Fitch (as even though I was on my own dime as a “volunteer”, it was assumed I’d be assigned one of the seats). He understood and went on his way. Later I ran into Bill Lloyd who expressed his regrets as he said Fitch told Briggs, he “couldn’t spare me, so the ride had been given to Karl Brocken.” Fitch then told me that I would have Ray Crawford’s seat if Crawford failed to attend the drivers meeting (he hadn’t arrived yet) and if he did, I’d be THIRD driver on the Fitch / Hansgen (No. 1) car. Crawford DID show up in time and any chance of subbing for Walt or John was a dream not achieved. Anyway, late in the race, we were in sort of a lull in the pits and I told Frank I was going to take a little “break”. He reached into his pocket and gave me his ring of keys and told me to stop by the shop and “pick up an engine — you DESERVE it!” I thanked him, and thought of it; but didn’t want take the time at that moment, so after some MORE orange juice and a stroll through the pits, I gave him his keys back with my thanks and explanation. At the time I didn’t know HOW fortunate THAT was as during the race “people” broke into the garage and stole a bunch of tools, etc. It was OBVIOUSLY an inside job and the thoughts were that it was some of the guys down from GM Tech that were helping; but I do not know if the culprits were EVER identified.

A couple of weeks later (or so it seems now) I got a phone call from Fred Warner asking, “What’s your shipping address?” Of course I asked what for and he replied “We’ve got something w’re going to send you”. A few days later a Railway Express (how’s THAT for dating myself?) truck pulls into the drive and two large crates are deposited in my folk’s driveway. One contains a complete Chevy engine taken from a vehicle run at the Arizona test facility, the other contained ALL the Duntov-inspired, Detroit Racing Equipment Co., etc., “goodies” to create a Sebring engine. When I realized this, I phoned Fred and asked “What’s the deal”. He replied that Frank thought I’d gotten the shaft and hoped this eased things” (or words to that effect). Anyway, I built up the engine and installed in my (ex-Bob Fergus) Austin-Healey 100, which is another story in itself. I brought it to Oklahoma when I came out to attend Spartan School of Aeronautics and had much fun with it. Squeezing down on the throttle in 4th gear at 90+ MPH could get wheelspin if you weren’t careful!

Again, THANKS for the memories (with apologies to Bob Hope!)

Ciao Peter

This has been a great series on the Cad-Allard, really good, enjoyable stuff and a sizeable contribution to American (and European) motorsport history. The cars, the drivers, the people generally – they’re all there.

Many thanks for that.

Jim

Does anyone know of any photographs of Briggs Cunningham’s customized 1949 Cadillac Sedanette. I remember looking at it in December 1954 while visiting the West Palm Beach factory. It was Dark Green, likely the emerald metallic green used on many Cadillacs of the era. The taillights were lowered in the rear fenders much like the Adams Cadillac coupe that Coachcraft of Hollywood built. As I recall it had some of the typical Conn. vanity plates like Briggs had on many of his cars.