By Gijsbert-Paul Berk

The mighty influence of Citroën (minority shareholder but major client) in the running of Panhard became most apparent when the Panhard management in 1959 started to plan a successor of their PL 17. Monsieur Pierre Bercot, Citroën’s boss, made it clear to Jean Panhard that they would not support the Panhard Company to invest in the development of a new mid-sized ‘berline’ (four door sedan). His argument was that Citroën was shortly going to introduce the Ami, an upgraded version on the platform of the 2CV and was already working on a totally new mid-sized model (the GS) to be launched in 1970. It would be a folly to compete with each other in this segment.

However, it was agreed that there was room in the Citroën/Panhard range for a sporting two-door coupé. Thanks to its many victories in rallies and at Le Mans, the name Panhard was associated with successful small high performance cars. They should now cash in on this favorable image. Thus the idea was born to develop the Panhard 24 (the name linked to the famous 24 Hours race at Le Mans).

Panhard’s last struggle

Considering the limited financial means available at Panhard et Levassor, Louis Bionier, assisted by André Jouan and René Ducassou –Pehau created a real masterpiece. They designed a very stiff monocoque construction made up from pressed steel segments combined with a tubular frame that supported the flat roof. It was a completely new structure, but for reasons of economy they had to use the front and rear sub-frames that contained the suspension units, engine and transmission from the PL 17. The wheelbase of the new coupé was 2.286 m (90.0 in). Its new two-door body measured 4.267 m (168.0 in) in length, was 1.62 m (64in) wide and 1.22 m (48 in) high. A striking feature was the light glass house covering the cockpit. Another detail was the prominent horizontal groove with an Inox (polished stainless steel) strip at waist level to accentuate the lines of the car. This became a fashionable styling element at the time and is also found on the Chevrolet Corvair, the NSU Prinz and the Fiat 1300 /1500 sedans.

The downward-sloping front was fitted with twin headlights, mounted behind glass covers. This was not only for aesthetic reasons but also improved the aerodynamic characteristics. In 1967 Flaminio Bertoni adopted a similar solution for the headlights of the Citroën DS.

On 24 June 1963 Panhard presented the 24 2+2 coupé to the press at the Montlhéry race circuit. As Bionier was very concerned about both active and passive safety, the new Panhard was the first French car to offer seatbelts as an option. Passenger welfare was furthermore improved by an elaborate system to get warm and, if wanted, cool air into the interior of the car. During the gestation period of the 24 the Panhard design team had proposed to equip the new body with a four-cylinder Citroën engine as well. Although at first this idea was approved and there were even two prototypes tested, the bosses of Citroën suddenly blocked further development, for reasons of cost. With hindsight this seems an unbelievably stupid decision because such a Panhard /Citroën, combining the low weight and the sporting styling of the Panhard 24 C body with the proven engine of the DS would have made an attractive Gran Touringcoupé. It would certainly have been a less expensive adventure for Citroën than the later Maserati-engined SM.

A daring concept that unfortunately never came into production. But one of the two prototypes is still exhibited in the Conservatoire Citroën at Aulnay-sous-Bois, North of Paris. Its body is recognizable as a Panhard 24 CT, but with a longer nose. The chassis, suspension and engine were adapted from the Citroën DS. It has a wheelbase of 2,628 m and could reach a top speed of about 200 km/h

Therefore the buyer of a Panhard 24 could only chose between one of the two 848 cc air-cooled flat twin engines. There were two versions: the 24 C Coupé with 42 bhp (50 SAE bhp) and the 24 CT Coupé with the 50 bhp (60 SAE bhp) Tigre engine. As the 2+2 coupé weighed only 840 Kg (1,900 lb.) these engines provided adequate acceleration but the cars were not as fast as their sleek body suggested. However, from 1965 onward the most expensive 24 CT, equipped with the powerful Tigre 10 S was capable of reaching 160 km/h (100 mph). Initial sales of the 24 C were disappointing and after a year only the 24 CT remained in the sales brochure.

From 1965 the longer 24 B and BT became available. Their wheelbase was extended to 2,550 m (100.4 in) and this provided more legroom for the rear-seat passengers. These B versions, although they still only had two doors, were sold as four/five-seaters. The Panhard 24 was also available with a very attractive cabriolet (convertible) body. This substantial transformation needed strengthening of the chassis structure and was outsourced to specialist coachbuilders. The Panhard 24 series remained in production until 1967 and in total 28,651 were produced.

Designing the Citroën Dyane

The end of Panhard as a car manufacturer did not mean the end for Bionier as a coachwork designer. In April 1965 Citroën assumed total control of Panhard’s automotive activities, and from 1967 the factory at the Avenue d’Ivry only produced the Citroën 2CV van. Citroën continued producing the military vehicles in a plant at Marolles-en-Hurepoix. After the merger of Citroen and Peugeot, PSA sold this activity with the right to use the name Panhard to the group Auverland Automobiles. However Pierre Bercot, the boss of Citroën had other problems as well.

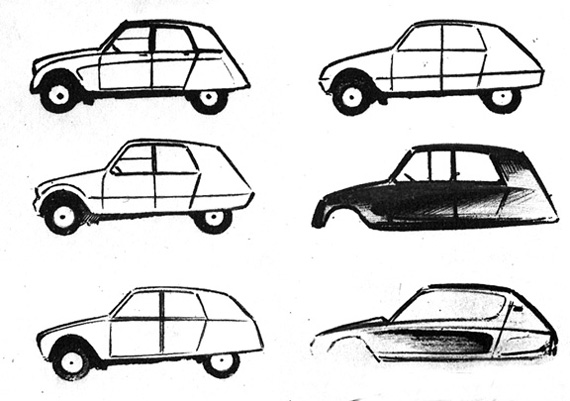

Some early sketches the Citroen Dyane, the intended successor of the famous 2 CV or Deuche. (Courtesy “Toutes les Citroën” by R. Bellu)

The new front-wheel drive Renault R4 proved to be an attractive alternative to the 2 CV and this was reflected in their sales figures, so they needed to stop this erosion with a more modern body for the ‘Deuche’. Unfortunately Flaminio Bertoni, the famous director of their design studio, had unexpectedly died and Robert Opron, his promising protégé, was still to be promoted as his successor, so Bercot decided to outsource the construction and styling for the new 2 CV body to Panhard and their experienced designer Louis Bionier. Bercot’s brief consisted of four conditions:

1. – The body of the new car must have a fifth door as on the Renault R4.

2. – For economical reasons the new car had to use as much 2 CV and AMI components as possible.

3. – For the same reason it had to be produced jointly with the 2 CV on the existing production lines. This determined the dimensions.

4. – For fiscal reasons the engine capacity had to be limited to 2 CV (the Renault had 4 CV). Bonnier made his first sketches and drawings, but by the time he had finished them Opron was fully in charge at the design studio at Citroën. As is often the case with young managers he wanted to make his own mark. The NIH (not invented here) syndrome probably also played a role. So the body of the Citroën Dyane (introduced in August 1967) was partly the work of Louis Bionier and partly that of Jacques Charreton, a new designer just engaged by Opron for his team.

The Citroen Dyane was the result of the more or less forced collaboration between Louis Bionier and the Bureau d’Etude de Style at Citroën.

There is however no doubt about the origin of the name Dyane. Panhard had patented it together with the names Dynamic, Dyna, and Dynavia and since the takeover it was the property of Citroën.

Postscript

When his job for the Citroën Dyane was finished Louis Bionier retired. After more than half a century with Panhard – and some rather frustrating years – he had certainly earned it. Because taste is very personal, you may love his designs or loathe them. But they cannot leave you indifferent and you must admit that all his creations had a distinct character. Bionier was a man with brilliant ideas and was also a hard and very conscientious worker. His idea for the split ‘A’ pillar for the Panhard Panoramic was innovative and indeed improved forward vision at a time when few designers took road safety into consideration. Long before WWII he sought the most effective aerodynamic shapes without sacrificing interior space or headroom. In his later years he was one of the first to fathom the possibilities and problems of an all-aluminum monocoque body. Certainly, some of his designs were influenced by others but some of his designs have in their turn undoubtedly inspired other designers. That is the way the automobile industry functions. The international motor shows are a regular source of cross-pollination.

Bionier always aimed for perfection, not only from his collaborators but also from himself. In his mind aesthetics had nothing to do with an inspired but lucky stroke of a pencil or paintbrush, or with fleeting fashion. A good design should respect the established laws of physics. In this respect Louis Bionier was a typical engineer/designer, but he had many artistic talents as well. He played a violin and was a passionate photographer and amateur filmmaker. He also designed decors for his wife’s photographic studio. At the same time he was a family man who loved his spouse, his house and his garden. He passed away in 1972, but enjoyed life till the end.

BIBLIOGRAPHY / SOURCES

Panhard, The flat-twin cars 1945-1967 and their origins

Author David Beare / English language

Published by Stinkwheel Publishing, UK – 2012

ISBN: 9780954736323

Toute l’Histoire Panhard

Author Benoît Pérot / French language

Published by editions E/P/A, Paris – 1994

ISBN: 972851204440

Panhard et Levassor, entre Tradition et Modernité

Author Bernhard Vermeylen / French language

ISBN: 9782726888064

Les Panhard et Levassor, une aventure collective

Author Claude-Alain Sarre / French language

Published by E.T.A.I. éditions, Paris – 2000

ISBN: 9782726885277

Automobilia, Toutes les Voitures Françaises

Numéros des Salons 1934 -1966

Author / editor René Bellu / French language

Published by Histoire et Collections

5 Avenue de la Republique, 75541 Paris Cedex 11

50 Ans d’Automobile

Author J.A.Grégoire / French language

Published by Flamarion, Paris -1974

Depot legal 4e trimester 1974:

Editeur No. 8164 – Imprimeur No. 4973

40 ans de création publicitaire automobile

By Alex Kow. Published in 1978 by Edition Maeght, France

French text but many large illustrations

Hardcover, 176 pages 30 cm. x 24 cm.

Sirs,

Very, very nice article vis a vis the Panhard 24 (Bt /Ct)….Acutally I have had two 24bt’s….one at this moment sittin in my garage here in West Virginia…long way from France…but it is happy…very neat car…the Engine, as they say in France “Incroyable!”

Thanks

jimBandy