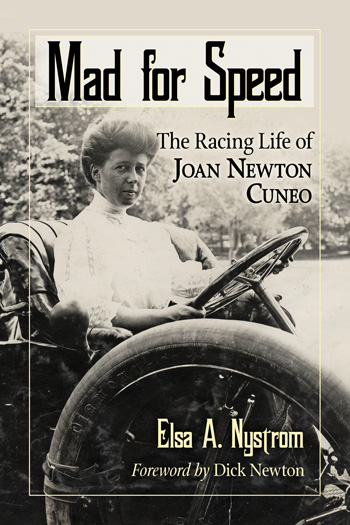

Mad for Speed, the Racing Life of Joan Newton Cuneo

Mad for Speed, the Racing Life of Joan Newton Cuneo

By Elsa A. Nystrom

217 pages, softback, black and white photos

ISBN 978-0-7864-7-93-8

$39.95

Published by McFarland www.mcfarlandpub.com

Available at Amazon.com or order from 1-800-253-2187

Review by Pete Vack

Photos courtesy the Author and the Newton Family

In 1909, Joan Newton Cuneo, all of 5 foot 2 inches and 125 lbs., competed against a top-notch field of professional men race drivers in a three day series of races held in New Orleans just prior to the Mardi Gras. With her new 50 hp Knox Giant, she easily won her races in the amateur divisions. What turned heads however, was that this tiny dynamo came in second to the future Indy winner Ralph De Palma in the 50 mile event, and again finished second to De Palma in a 10 mile race the next day, beating drivers Bob Burman, Lewis Strang and George Roberston. France’s Madame du Gast had nothing on the petite Mrs. Cuneo. Cuneo, already a proven fearless and talented competitor, was quickly becoming the Danica Patrick of her day.

Less than a month later, the Automobile Association of America, already in bed with the car manufacturers and in full control of all sanctioned racing in the U.S., officially banned women from racing or any other type of time trial or Tour.

Taking the heat

It was Joan’s fault, or so went the legend, often abetted by Cuneo’s own remarks. Perhaps she was just too good, and the results did not please the board members of the AAA. It would be almost 70 years and a new sanctioning body before a woman was ever allowed to race the ovals again in the U.S. It was not until 1976 that Janet Guthrie attempted to qualify at Indy.

However, author (and professor of history at Kennesaw State University) Elsa A. Nystrom, in her excellent book, Mad for Speed, has determined that by the time of the New Orleans Mardi Gras Car Carnival, the decision to ban women from competition had already been made; it had nothing to do with Cuneo’s remarkable successes.

Cuneo’s supposed role in the banning of women from racing plays a part of Nystrom’s saga, but there is a larger, more interesting story here and Nystrom tells it well. Joan Newton, one of the wealthy Newtons of Holyoke Massachusetts, married Andrew Cuneo, an immigrant banker from southern Italy, who promptly allowed his new bride to drive and then race the latest and most powerful cars then built. This was not conventional behavior for a well-bred member of the WASP Victorian society. Mr. Cuneo goes one even better, hiring neighbor Louis Disbrow, just off a sensational murder rap, to be a riding mechanic and overall guy Friday to support Joan’s racing and touring efforts. Mrs. Cuneo then enters three grueling long distance Glidden Tours with her young and handsome riding mechanic (although Mr. Cuneo was also a passenger on some of the Tours) and many other races, rallies and exhibitions. Along the way, the tiny but outspoken Mrs. Cuneo becomes perhaps the best women racing driver of her era and certainly the most famous.

Cuneo and mechanic Disbrow ford a stream in the 1909 New York to Atlanta Good Roads Tour. Tours such as the Glidden were established to help bring attention to the need to improve the nation's road system.

Aside from the aforementioned Madame du Gast in France (France banned women from racing in 1904) there were few contenders to the throne. To add balance as well as more insight, Nystrom has included a chapter on Cuneo’s female contemporaries and rivals, including, Alice Huyler Ramsey, the first woman to drive across the U.S., Dorothy Levitt, who drove Napiers in the U.K. with some success (Nystrom believes that while Cuneo was no doubt the best woman driver in the U.S., Dorothy Levitt may have been a little better.), and Blanche Stuart Scott who went from cars to airplanes as women were ironically not banned from airplane competitions.

Joan Newton Who?

All of this is new and most welcome material. As famous as Cuneo was in her time, she is almost unheard of today. According to Patricia Lee Yongue, writing for VeloceToday in 2005, “The history of women in auto racing in the United States is just beginning to emerge–and still only in fits and starts. The research is difficult, most information, and most of that scant, buried in small town newspaper archives and presumably in as yet inaccessible private correspondence and journals. Racing history books pay little, if any attention, to women racers.”

Linking with the family

By Internet Serendipity, in early 2011 Nystrom hooked up with ex-SCCA racer Richard Newton, who would often google ‘Joan Newton Cuneo’, hoping to learn more about his great-grandfather’s brother’s daughter, who the family had claimed was not only a famous race driver but a bit of a black sheep as well. Nystrom had already gathered a lot of material, but linking with Richard Newton provided access to the family relatives and photos and the impetus to finish what would be a very complete and revealing look at the life and times of Joan Newton Cuneo. Newton also wrote the Foreword and at the end, writes about how difficult it must have been to drive a car like the Knox Giant at speed, particularly for a petite woman.

A darker side

Yet because Nystrom’s book is so complete and well-documented, some readers may get a sense of another side to Cuneo. No one ever claimed race drivers were angels, even female race drivers. Cuneo was extremely competitive, confident and daring as she must be, and yet the portrait that emerges shows that this mother of two children could also be somewhat irresponsible and, for all her virtues, was able to shrug off laws meant to protect the populace at large, causing the indignation of local judges. More serious were a series of accidents, one of which involved the possible death of a young boy, another which could have been construed as a hit and run during the 1908 Glidden Tour, and a third involving a horse and carriage. Was it for this reason Cuneo was possibly regarded as a ‘black sheep?’

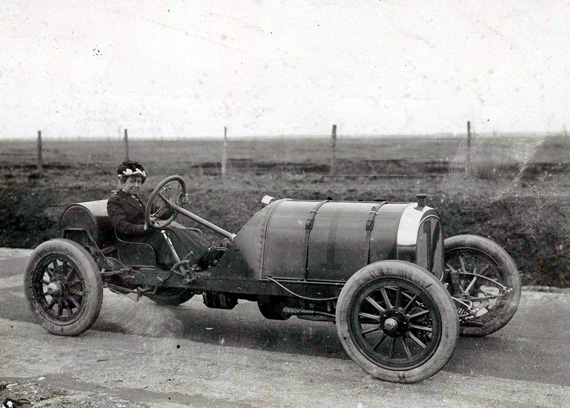

Cuneo and Disbrow unofficially entered the Giant's Despair Hillclimb. The Knox has been stripped for racing. This was shortly after Cuneo was banned from AAA sanctioned events.

Obstinate Triple A

So what was the problem with the AAA? Nystrom reveals that there were complex reasons for the AAA ban, (no official reason was ever given, no meeting minutes, no smoking gun) but perhaps the most realistic obstacles involved just plain-old-bias against women, and the fact that the manufacturers were very worried that an accident, particularly a death, involving a women driver would have a very negative affect on publicity and therefore sales. Both are believable reasons, despite the fact that the death of Nina Vitagliano at Ascot in 1918 in a Stutz did not produce the kind of outcry the manufacturers were afraid of. (Nystrom points out that Nina’s death occurred in the west, where women were allowed more freedom (and drove more) and it wasn’t AAA sanctioned.) Yet their fears were legitimate; the public (and media) is fickle and prone to finger pointing. As far as the bias, well, yep.

Name that Lancia

And what happened to Joan Newton Cuneo? Her husband decides to have a mistress, who got a bit greedy and sued him for breach of contract. He counter sues, recovers, but of course the damage has been done. The plot thickens but we’ll let the astute reader find out for themselves, and perhaps help nail down the kind of Lancia she drove in a Ladies Endurance run in 1909.

Par for the course for McFarland, Mad For Speed is a well done, thoroughly professional book complete with a full index, notes, and bibliography. Sadly, the use of an off-white pulp paper does nothing to enhance the wonderful contemporary images gathered by Dick Newton and Nystrom.

Mad for Speed reads like a good historical book should—like a novel with footnotes (and good footnotes at that!) Nystrom carries on the tradition of the late Beverly Rae Kimes and Barbara W. Tuchman, being at once a true historian and an interesting writer. We need more like her.

Good grief! the late and wonderful car journalist/photographer Pete Coltrin’s middle name was Cuneo! And he looked 80% just like her, to my eyes! Are they related? Anyone know how to contact Lella Coltrin in Modena to see what she might know?

Actually they were not related. Joan Newton’s husband Andrew Cuneo was adopted by his uncle. His birth name was De Martini. Joan was the daughter of John Carter Newton and Leila Vulte.

This was verified by both census records and the families.

EN

The two photos of Joan Cuneo on her Knox shows two different cars but the caption to the lower photo implies that the cars were the same. The top car does not appear to be chain driven, though the chain could be hidden by the wheel. The radiators are different and why would you raise the seating on a “racing” car? The chassis to the rear of the front of the rear spring is quite different. Was there two Knoxs in Joans’ life or is it all explained in the book?

According to the book “La Lancia” written by Wim Oude Weernink the Savannah GP Lancia was a Corsa version of the production 12HP or later named Alfa model. The engine is unknown, it could have been a Corsa 12HP, a one off Corsa engine with overhead valves or a development engine for the forth coming 18HP Beta model.

Yes, they are both Knox cars but the first one is not stripped for racing, as it is in the second photo. And yes, Joan did have two Knox cars which she raced. Unfortunately she didn’t get the second until women were banned from racing. She was racing at Giant’s despair in an unofficial category. They are both chain driven. And yes it is explained in the book. Joan never had a purpose-built race car. She drove the car around town and took everything that could be removed off for racing.

If Joan Cuneo competed in a new Knox at the 1909 event it would have been a shaft drive car, which the top photo shows. Knox changed to shaft drive in 1907 ( The New Encyclopedia of Motor Cars – GN Georgano )

The bottom photo shows a pre 1907 car, “race prepared” possibly for the first hillclimb at Giant’s Despair in 1906.

The ban on women racing was not until after the 1909 event, therefore Joan Cuneo had raced both cars.

Mr. Sales,

Thanks for pointing out that the Knox Joan is posing in has a shaft drive. We didn’t notice as we were more interested on the message on its back, as it was a family photo. As it turns out, that Knox was a 38 hp model which Joan was driving at the factory. She did not own it. Both her Knox cars were 48 hp Giants which had chain drive. There are several photos of her in the book behind the wheel of the Knox Giant, one taken at New Orleans in 1909, with chain and Knox clearly visible. Joan’s racing career was fairly well documented in the newspapers of the day. She did not race a Knox until 1909. Before that she drove a Rainier (1907-08), Maxwell(1906) and White (1905-1906).She also drove cars that belonged to others, like the Lancia. The Giant’s Despair photo was taken in 1909, after women were banned; she drove the same car later in Vermont as part of a celebration. Joan was in Europe the summer of 1906.

EN