The Alfa 2300 Castagna, created in a period when the “pursuit of balance and elegance both in substance and shape expressed itself in sheer majesty.” Photo by Harry Hurst.

By Pete Vack

The four of us paused to stare at the lines of the 8C 2300 Alfa Romeo Mille Miglia Castagna Spyder, now on display at the Simeone Foundation. Had one the time, it’s something that could be done all day long with pleasure. Everyone agreed it was perfectly proportioned; the short wheelbase accentuated the long hood line and swooping fenders, and huge black wire wheels stood out against the red finish. “The Alfa makes it easy to appreciate pre-war cars”, said Harry Hurst, the Simeone PR director and author of Sebring 1970. “There is not a bad line anywhere.”

Tito Anselmi and translator Angela Cherrett put it nicely when they wrote that Castagna “…flourished during a period in which the pursuit of balance and elegance both in substance and shape expressed itself in sheer majesty.”

Today, we remember with honor the houses of Zagato and Touring; Castagna is often relegated to the background as they never designed cars for racing. Its roots were in the carriage building trade of the 1800s, and by 1906 Castagna was designing and building automotive coachwork for the royal family, one such being a Fiat Sparverio for the Queen Mother of Italy. Their specialty became luxurious carrozzeria for clients with Isottas, Lancias and Mercedes.

The Foundation has a display of cars which ran at Brooklands. And run this did, at 135 mph, driven by Guy Templer in 1939. The car has changed little since.

The Milanese firm was noted for decorative motifs along the beltline of certain cars, including a long wheelbase Alfa 1750. But none came with the distinctive curl that was evident on the 8C 2300. Embossed, so to speak, into the bodywork, was a graceful edge of a line that began at the grille on either side and terminated on each door in a circle. Purely decorative art deco, typical of Castagna, but also unique. When the car came into the possesion of Simeone, there was a thin line of white tape that highlighted the decorative line. “The tape had to be removed”, said Fred Simeone, “and it is harder to see the Castagna motif now.” The tape had to come off, but since no one knew if it was original or not, it was left off.

Castagna’s cutaway running boards artfully left a gap in the running board in the center of the car under the doors. The result was the many pits and stone damage to the front of the rear fender, left unprotected from full-length running boards. The problem reportedly caused one early owner to sell, as horse manure was constantly being tossed in the direction of the driver.

________________________________________________________________

If you are enjoying this article, why not consider a donation to VeloceToday? Click here for details..it’s easy!

________________________________________________________________

We turned our collected attention to the possibility that the paint was original, bearing in mind the age and history. Simeone Foundation Curator Kevin Kelly noted that the paint was very thin; if it was repainted, it had been taken down to bare metal. There were many instances of touch up, done for maintenance, the finish where a leather hood strap had been in use for years was shiny, and looked original. Despite a very long and well documented history, no one at any time mentioned an accident or a re-spray but one never knows. If not original, it was done in the 1930s while in Holland or Italy, perhaps taken down to bare metal to save weight for racing.

The Castagna emblem is placed on both sides of the bodywork. Note the paint—but just don’t paint. Leaving things alone may be difficult but necessary. Photo by Harry Hurst.

Yet that would be penny wise and pound foolish, as there are many easier ways to save weight on this admittedly heavy Castagna (according to Anselmi, all Castagnas weighed about 15 percent more than their Touring or Zagato counterparts). Hardwood hides under heavy aluminum panels, large steel tubes support fenders with inner fender wells (to protect the outer aluminum surface from debris) and everything is bolted rather than rolled, crimped or screwed. In some respects the Castagna 2300 appears similar to a Zagato, but underneath the differences are significant. No lightweight; if the Alfa 2300 Zagatos are the early 1930’s equivalent of a Ferrari 250 GTO, the Castagna Alfa equals the Ferrari Lusso. Yet no one had drilled one hole in an effort to pare pounds, so it would have been folly to remove paint.

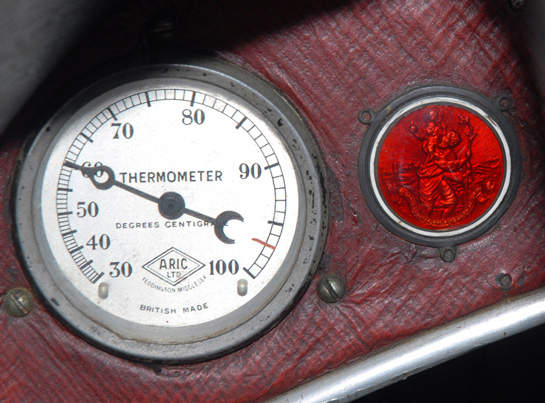

Unlike the usually Spartan Zagatos and (sometimes) Tourings, the Castagna body was able to afford a few niceties, such as tiny rubber door stops, rubber inlaid in aluminum strips on the running boards, two polished aluminum strips on the dumirons with no purpose but decoration, a Moto Meter, mesh covers for the headlights, and an almost posh leather interior.

Somewhere along the way an owner had added a St. Christopher’s medal to the leather dash. The patron saint of travelers, St. Christopher’s charm must have worked, for the Alfa had done a good bit of traveling in the last 78 years.

A St. Christopher’s medal is attached to the Alfa’s dashboard. The patron saint of travelers was a favorite of motorists during the 1920s and 30s. Here he is seen protecting a child from a snake. Photo by Harry Hurst.

I ask Fred if he thinks the car would benefit from a good polishing compound. It would be a step into the abyss of the restoration trap; the body looks a bit better and the Monza brass grille and cowl would need polishing, shine that and then rechrome the Alfa lettering, clean up the dashboard and seats and suddenly one is back to the old paint which now looks tatty again. Leave it, just maintain the appearance and leave it alone. Which is exactly as Fred like to find them– as last raced. Few cars in his 60 plus car collection so distinctly represent Fred’s long standing belief that cars should not be restored if they can be presented as they were in their prime, warts and all.

The radiator cowl is brass. It was painted the car color originally, but someone removed the paint and let the brass finish appear as natural. Note the stone guards on the headlights and the dumbiron trim pieces.

And what of Castagna? Founded by Carlo Castagna, his sons Ercole and Emilio took the firm through two world wars and continued to build road cars for their clients. But they never had a truly talented designer, and never wished to compete with Zagato or use new methods to reduce weight and complexity. One of the last Castagnas was an attractive but typically heavy Cisitalia spyder in 1947. Castagna closed its doors in 1953, just in time for the unit-bodied revolution which would make life very difficult for many small coachbuilders.

Taking a last look at the Alfa before getting back to work, Fred wondered out loud about today’s classics. Would a Bugatti Veyron be considered art in another 78 years? Would four men stop to assess and critique its existence? Would it be as exciting, or well proportioned? Or sadly, would anyone even care, in the year 2088?

We can’t know. But here and now, we knew and enjoyed.

.

Simeone Foundation Automotive Museum

6825-31 Norwitch Drive

Philadelphia PA 19153

(215) 365-SAFE (7233)

Fax: (215) 365-8230

The Simeone Foundation Museum is conveniently located just minutes off Interstate 95 in Philadelphia, close to Center City and the Philadelphia International Airport.

Museum Hours

Tues 10AM – 8PM

Wed – Fri 10AM – 6PM

Sat – Sun 10AM – 4PM

Closed Mondays

Admission: $12

Seniors: $10

Students: $8

Children under 8 free when accompanied by parent

ok,it was decided to remove the tape.however being to the fact that that it was’nt known as to its source why isn’t there a photo of the car with the tape? if one exists lets see it please.