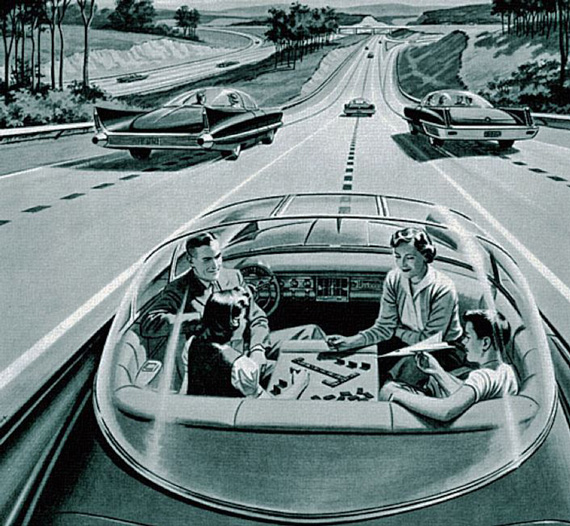

Playing scrabble while your car is driving itself on the Turnpike. As early as 1956 the Central Power and Light Company inserted this ‘inspired’ advertisement in leading US newspapers. Under the intriguing heading 'Electricity may be the driver', its text read: 'One day your car may speed along an electric super-highway, its speed and steering automatically controlled by electronic devices embedded in the road. Highways will be made safe – by electricity! No traffic jams ... no collisions ... no driver fatigue.'

Forget all of what you have considered major advancements in the development of the automobile: Ford’s assembly line, automatic transmissions, disc brakes, fuel injection, computerized fuel systems. By far the most important and far reaching automobile innovation since the very invention of the automobile is just taking form. ADAs (Autonomous-driving-automobiles) are not just around the corner but here, much to the delight of aging baby boomers who will never be immobile, and younger generations who will be able to play computer games and message text all while being driven automatically. Gijsbert-Paul Berk helps us understand where we’ve been, where we are going, and can we get there without the steering wheel and gas pedal.

Part 1

The well-known high-tech company and Internet search-site now intends to produce this urban ADA that even has no steering wheel. Legislators and managers in the car industry are skeptical about the feasibility of such a project in view of the high financial risk law suits over product liability. But Google is determined.

Reuss’s statements were a reaction to Google’s announcement last May that it is building and testing 100 fully autonomous vehicles. These little Google two-seat cars have no steering wheel, a crash-impact proof body and a top speed of 25 miles (40 kilometers) per hour. Google has confided the production of these robot cars will be done by Roush Industries, a specialist company in Allen Park, Michigan. Roush manufactures “automotive performance products and alternative fuel systems for fleet vehicle applications.” Up till now Google tested its technology in Lexus and Toyota Prius automobiles.

GM and Google are not alone; practically all the major car makers such as Audi, BMW, Ford, Geely, Honda, Mazda, Mercedes-Benz, Mitsubishi, PSA (Peugeot/Citroën), Renault-Nissan, Toyota, Volkswagen, and Volvo have announced they are testing and developing ADAs. So are a numbers of leading equipment manufacturers such as Bosch, Valeo, Continental, Michelin and others. Only Chrysler (Fiat) so far seems reluctant to follow the herd. Chrysler’s Dodge division even produced a commercial stating; “We will never let computers drive our cars.”

Protagonists of ADAs believe that they will be the most important revolution of the motorcar industry since Henry Ford introduced his Model T, which gave such a tremendous impulse in the popularization of the use of automobiles. They are convinced that modern technology, which permits planes to fly without a pilot on board (drones) and locomotives to run without a driver, can also take over the functions of car drivers. This seems logical. However, commercial aircraft, even if fitted with the most advanced automatic pilot system, still requires a captain and co-pilot in the cockpit. In addition, those planes travel through fly zones or corridors that are constantly monitored by air traffic controllers on the ground. Drones as well as driverless locomotives are always operated by remote control from command posts manned by humans.

But as projects such as VaMP, ARGO, the DARPA (see below) and the Google test have proven, autonomous driving automobiles are in fact already a technical reality [and to some degree now available on the new Mercedes-Benz S550 with the optional Distronic Plus cruise control – Ed.].

A history longer than one might think

At its 'Futurama' exhibit on the 1939 New York World Fair General Motors gave the public their first peek at the possibilities of self-diving cars. Visitors were seated in rows above a three-dimensional display showing a futuristic city center with a traffic flow of radio controlled electric automobiles. The ‘dedicated’ roads with integrated electric cables provided electromagnetic field transmitted the power to propel the cars.

The idea of driverless or autonomous driving automobiles is not new. As early as the mid-1920s inventors experimented with remote controlled radio systems. In 1939 General Motors showed their Futurama exhibit at the New York World Fair to millions of visitors. A major display featured the possibilities of autonomous driving in crowded city centers with electric cars that were powered by circuits embedded in the road surface and controlled by radio waves.

Overview of the mock-up made for the General Motors presentation at the 1939 New York World Fair gives some idea how the exhibit looked. As this close-up shows, the animation at the Fair was far more life-like. Norman Bel Geddes designed GM’s Futurama pavilion.

During the years just before and after WWII, research on self-driving cars mainly concentrated on establishing ‘communication’ between ‘dedicated’ roads equipped with electromagnetic circuits and the cars being driven on them.

As part of such an experiment, in 1958 the Nebraska Department of Roads fitted electric circuits in the pavement of a 400-foot long section of a public highway just outside Lincoln, to allow life size tests and demonstrations with a guiding system developed by RCA in collaboration with General Motors.

A 1958 Chevrolet like this one was probably the first self-driving car in the US. It participated in an experiment carried out that year on a specially prepared new intersection on the outskirts of Lincoln, Neb. Two of these Chevrolet passenger cars were equipped with special RCA (radio Corporation of America) radio receivers and audible and visual warning devices that could activate the steering mechanism, acceleration and braking. Detector circuits buried in the road surface by the Nebraska Department of Roads. A series of lights along the edge of the road determined the place and speed of the vehicles on the pavement and transmitted radio impulses to guide the cars. It was proven that the system worked well.

During the 1960s, the United Kingdom’s Transport and Road Research Laboratory did a series of tests with a driverless Citroën DS that interacted with magnetic cables embedded in the road surface of the test track. The test-car was driven at speeds up to 80 mph (130 km/h) in different weather and wind conditions, without any deviation of direction.

During the 1950s research for autonomous driving was mainly concentrated on systems that would allow roads to influence the behavior of cars and so eliminate driver errors. Here we see a display to demonstrate how such a system could work. In 1958 at the initiative of L.M. Hancock, traffic engineer and his director L. N. Ress of the Nebraska Department of Roads, this company molded electric circuits in the pavement of a 400-foot long section of a public highway just outside Lincoln. This made life-size tests and demonstrations possible with a guiding system developed by RCA in collaboration with General Motors.

But the scope of the research changed. The engineers were switching from developing dedicated (or intelligent) road systems to designing robots for dedicated (intelligent) automobiles. There were several reasons: Transforming existing road networks with electromagnetic detecting circuits would involve astronomical costs and few governments could afford such investments; the incredible advance of computer and robot technology allowed researchers to create small devices that could be fitted on normal production cars; and finally, governments and industry joined forces to help and finance R& D centers and universities to realize new ideas.

“Prometheus” funded realistic projects in Europe

With a grant comparable to 749 million of today’s Euros, the European Commission was one of the main sponsors of the Eureka/Prometheus (PROgraMme for a European Traffic of Highest Efficiency and Unprecedented Safety) project. Both universities and the industry contributed in this project to research new forms of automated driving that took place between 1987 and 1995.

At the Bundeswehr Universität in Munich, Germany, in 1980 Ernst Dickmanns and his team developed a vision-based robotic guiding system. It was installed in a driverless Mercedes-Benz van and tested on city streets that were closed for other cars. The Mercedes respected all the traffic lights and still averaged 63 km/h (39 mph).

The incredible autonomous-driving VaMP and VITA-2 which the team at the Bundeswehr Universität constructed were based on Mercedes-Benz 500 SEL saloons. From the outside no one could distinguish them from a standard Mercedes. This was a great advantage when testing the cars on public roads. Other traffic was not aware that they were being overtaken by driverless cars.

The next achievement of Dickmanns’ team was even more impressive. It was code named VaMP and is considered to be one of the first perfect functioning robot cars, as they were called at that time. In 1994, the VaMP, and its twin the VITA-2 (both based on Mercedes-Banz 500 SEL saloon cars), drove autonomous more than a thousand kilometers on the Autoroute A1, the dual-lane motorway to the Paris Charles de Gaulle airport in France.

During their long distance tests VaMP and VITA-2 encountered all kinds of traffic conditions and sometimes reached speeds up to 130 km/h. The cars drove autonomously in convoy and separately, and wove in and out of traffic lanes, overtaking of other cars, without anyone touching the steering wheel or pedals.

The ‘Mille Miglia Automatico’

Here we see the self-driving ARGOS Lancia Thema on an Autostrada in northern Italy, doing the well-publicized ‘Mille Miglia Automatico’. This was run at an average speed of 90 km/h (56 mph). But the journey took six days because the team stopped in every city to allow the public a peek at the car and its advanced equipment.

In 1996 as part of the Eureka/Prometheus project, a team at the University of Parma, Italy, led by Professor Bianco and Alberto Broggi (now also a Professor) developed ARGO. This system used two low-cost black-and-white video cameras and stereoscopic vision algorithms that made it possible to ‘understand’ the ‘surroundings’ of a car. A slightly modified Lancia Thema equipped with ARGO technology proved to be able to follow normal (painted) lane markings on unmodified roads. In 1998 collaborators of the University demonstrated its potential during the well-publicized 1900 kilometers (1200 miles) long ‘Mille Miglia Automatico’ on the Autostradas of northern Italy. The car drove with an average speed of 90 km/h (56 mph) over a distance of 1900 kilometers (1200 miles) and during 94% of the distance it operated in a fully autonomous mode.

The US Army steps in

No it’s not Martians landing on earth. This is one of the early self-driving vehicles that participated in the Grand Challenges organized by DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Project), the Pentagon’s research agency. During the first of these Grand Challenges, none of the robot cars completed the course. But in the last, held in 2007, six cars made it. By then the course included driving through urban areas and the autonomous-driving vehicles were more or less looking like normal cars. First place was heavily contested between the teams of the Carnegie Melton University from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and Stanford University from Palo Alto, the winners of the previous challenge. But after 4 hours 10 minutes and 20 seconds, the robot car of Carnegie Melton beat them with a lead of 19 minutes and 9 seconds.

In the mid-2000s the US government set the ball rolling again by funding a number of military tests. This allowed DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Project), the Pentagon’s research agency, to organize three Grand Challenges, Demo I, Demo II and Demo III. Originally only organizations that had links with the army were allowed to participate, but as this excluded universities, the rules were changed. Important money prizes (first prize was $2 million, second $1 million and third $500,000) were awarded for unmanned ground vehicles that succeeded to navigate miles of difficult off-road terrain, avoiding obstacles such as rocks and trees. The vehicles also had to follow the indicated route in the shortest possible time. One can very well understand the strategic value of such experiments for the military forces.

A huge market?

Egil Juliussen, an analyst at the global information company IHS, predicts that by 2035 there will be 11.8 million self-driving cars on the roads. He expects that in 2050, almost all cars have become self-driving. Lux Research, another independent research and advisory firm, has published a report predicting that by 2030 the total market for ADAs will be worth $87 billion. The Chinese market alone will then account for $24 billion. Are these predictions too optimistic?

Whatever the market, it may be the legal hurdles that slow the process down.

Next week: The Technology is easy, Legals tough

Most importantly for the driving enthusiasts to consider is that any laws permitting self driving cars must also preserve the human permission to drive all of the existing road network with no autonomous controls. These devices will catch on very fast, lots of “the others” actually do not like to drive. Huge market, and it will get much safer for those of us who enjoy the art of driving.

I’m pretty sure that first Futurama photo is from the 1964 World’s Fair, not the 1939 version!

I’m pretty sure you are correct as well! Letsee if we can find the right year…readers, any help? Editor.

When searching on Google the photo does indeed show up as credited to the 1939 Futurama exhibit. It is posted here: http://cottagecheesevintage.blogspot.com/2013/01/1939-new-york-worlds-fair-world-of.html

Looking back on over 50 years of driving exotic autos, at my advanced age, I fail to understand the allure of the self-driving car. Maybe it is the answer to a “California Dream”, the utility of personal transportation that is available for use while “stoned”. My only reason for choosing the cars that I did, was the tactile experience, which would undoubtedly be lost in a robot car. I have owned boats with automatic pilots, but that had more to do with the difficulties of maintaining a course when being tossed about by an ocean. I guess that my feelings would be alien to the “poser” who owns a car for personal enhancement

I believe the Futurama picture is, indeed, from the 1939 World’s Fair. A quick Google search reveals a series of supporting images, as well as the reproduced photo used in this article.

Just ran across this article in doing research for a story. Nebraska’s trial run occurred in October, 1957, not 1958.