Hardback, 192 pages, 200 photos.

$79.95 USD, plus $20 Shipping

By Andrew McCredie as told by Paula Reisner

VelocePublishing Ltd.

Dorset, England

ISBN 978-1-845842-49-9

Order here through VeloceToday

The Irrepressible Frank Reisner and his Creations

By Pete Vack

Photos courtesy of the author and Veloce Publishing

I couldn’t help thinking of Frank Sinatra when I read Andrew McCredie’s book, “Intermeccanica, The Story of The Prancing Bull”. We all fall down and pick ourselves up and get back into the race, and we all think we do things our way, but Frank Reisner really, really did, even more than ol’ blue eyes himself.

The name Frank Reisner has been in constant use for about a half century in the pages of car magazines, but only now has Andrew McCredie put all the pieces together, put down the whole story, and created an automotive history and biography which is enjoyable and extremely informative. Though Reisner died in 2001, his wife Paula and his sons provided McCredie with reams of new material, documents, photos, insights, and anecdotes about Reisner. The story is so complete that it’s very hard to realize that Frank himself did not contribute to this tribute.

That his family can recall so much and have so much to say about Frank Reisner is a compliment in itself. Obviously he was someone everyone loved and willingly followed. After his death, family and friends caringly saved the memories and mementoes and McCredie’s book is a tribute to the man and the cars.

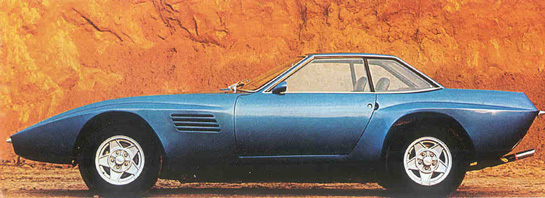

On the surface, his life seems like an automotive dream come true. In reality, like Sinatra, Reisner was up and down and over and out so many times he lost count. His first car, the Intermeccanica F. Jr., (read about the IM F. Jr.) was a one off project that led to the creation of the IMP, a tiny aluminum GT based on the Steyr Puch. That was nipped in the bud, presumably by Abarth. His next venture was to build the bodies for the Apollo. That eventually failed but with that came the more successful Griffith/Italia, the Torino/Italia, the Indra, Murena, one offs Centaur and Phoenix, not to mention the SpeedsterKubelwagen replicars made in California and Vancouver. No matter what happened–and just about everything did–for most of his working life when things went bad he simply started over again, always the optimist, always the enthusiast. He also suffered from a chronic lung disease for much of his life which eventually proved fatal at the still-young age of 69.

McCredie figures Reisner was so unsinkable because he had been through so much at a very impressionable age. Born in Hungary in 1932, his father was called up to serve in WWII even though he was too old and had already fought in WWI. His family thought he had been killed at the front, but miraculously Reisner’s father turned up after the war was over. But he lost his grandfather to the holocaust and found his life changed irrevocably when faced with an unexploded bomb which had landed in their home. The bomb didn’t detonate but the experience changed his attitude toward life. After the war, his family migrated to Canada, where Frank worked his way through college at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

He did things his way. Not many people would dare to show up for a first job at American Chemical Paint Company at the height of the McCarthy era driving a car (A Skoda) made behind the Iron Curtain. He was told to go buy an American car. Instead he bought a VW and saved money, not sure of what the future might bring. The future became clear when, after meeting and marrying Czech-born Paula, he built a Devin bodied VW, and traveled around the U.S. Both missed their homeland and decided to take a trip to Europe before setting down. “It was the beginning of an 18 year vacation,” recalled Paula. But it was no vacation. From 1958 to 1975, the Reisners worked hard at doing things his way, and building cars in Italy with imagination, flare, and a fair amount of success. To allude to another show business phenomenon, Frank and Paula’s success in Italy was about as real life as Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney saying “Hey, let’s put on a show” in their MGM heyday. “Hey, we’re in Italy, let’s build a series of exotic sports cars!” Only in Hollywood and Turin might something like this really have happened. And only during the golden era of the post war years could this have happened like it did. When those years were over–by the mid 1970s, so was Reisner’s dream.

Intermeccanica, the company Reisner created in 1959, was a jack of all trades. Initially, it was to construct and sell tuning kits, with an eye toward the U.S. and European market. This did reasonably well. Lured into Formula Junior racing by genius mechanic Carroll Smith, at the request of one of his dealers in Chicago, Reisner played conductor to a variety of Italian specialists who then built the rear engine Conrero-modified sleeved-down Peugeot engined Formula Junior. (McCredie devotes a chapter to this episode, but provided no information about the car’s existence after 1963. So we did.) Along with that, and an order for ten more F. Jr. Peugeot engines gave Frank and Paula enough money to invest in his next great idea, the Fiat 500 cum Steyr Puch based IMP.

He was off and running, both as a major subcontractor to other small firms like Apollo’s IMC and later as a full manufacturer. For Apollo, Reisner refined the design, and constructed the bodies, made ready for mechanical units for final assembly finish back in the U.S. In this instance, Intermeccanica served as a coachbuilder. The Griffith started the same way, but eventually the same car, marketed as the Italia, was made at Intermeccanica, making Reisner a car producer. In a deal with a Triumph dealership chain, Intermeccanica built and shipped out 176 Italias, the firm’s greatest success. After a move to the New World, Intermeccanica produced Porsche replicars from a fiberglass mold. Whatever Intermeccanica was, it was an extension of Reisner’s imagination and drive.

McCredie hustles the book along chapter by chapter in car and chronological order. From the IMP to the Apollo, to the Griffith to the Omega, Italia and Indra, he interviews many of the players, but largely relies on Paula’s recollections. Since she was there, so much a part of the company and worked side by side with Frank, she relates the often heartbreaking stories in vivid detail. This is a riveting story not easily set aside.

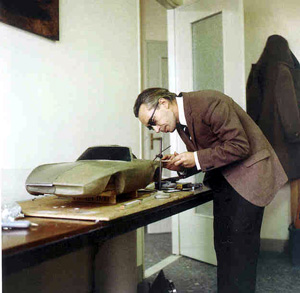

Reisner was smart enough to call on the best designers available for his projects, establishing a relationship with Franco Scaglione to clean up the lines of the Apollo. He retained Scaglione until he left Italy in 1975, and the two created the stunning Indra, Scaglione’s last automotive design. During the last years in Italy, Reisner worked with GM’s Bob Lutz on the Indra. Lutz witnessed another side of Reisner. “Frank was a guy who had boundless optimism, enormous will, but he was also often unwilling to accept reality, and would just explode in these fits of rage.” The rage may have been triggered by the cortisone treatments needed for his lung disease, but Reisner wasn’t always easy to deal with. The deal with GM to provide Opel engines and running gear for the Indra fell through, in part because Reisner refused to allow GM to build the cars in one of their own vacant factories in Germany. Paula noted that “Frank never wanted to be controlled by anyone else, so there was no way he’d move there.”

Italian style with American muscle was what it was all about, even if a tight fit, as here with the Indra.

The failure of the Indra in the early 1970s was also due to the poor economy, gas crisis, labor problems in Italy, DOT/EPA regs in the U.S. and a number of other problems outside of Reisner’s control. The family, now with three children, left Italy for Southern California, where they had to start from scratch once again, losing almost all of their possessions along the way. Six years and a failed lawsuit against GM (for conspiring to prevent Reisner from obtaining GM engines, thereby destroying the Indra business) the Reisners took their budding replicar car company to Vancouver, Canada.

Perhaps Paula best summed up her late husband when she said Frank “was a guy who was happiest when he had a new problem to solve.” In Reisner’s busy life, there was never a lack of things to be happy about.

There are a few items that need to be corrected or researched; it was Scaglietti and Morelli who conceived of the Ermini bodywork from which Devin took the mold for his fiberglass bodies, Porsche didn’t cancel the 550 project but expanded it, the first Italian rear engined Junior was the Branca Moretti. More importantly, the author claims that Carlo Abarth put an end to the IMP Stery Puch project, but provides no documentation or primary source collaborative interviews to support the claim (though it is both feasible and reasonable to assume Abarth may have been miffed by the competition.) There is no bibliography or footnotes but there is an appendix with the full list of cars built by Reisner while in Italy, complete with serial numbers.

However, none of this detracts from the book as a whole. McCredie has done an excellent job, telling Reisner’s story with humor, intelligence, enthusiasm and dignity. I liked it.

Goodness, do you guys have a proofreader?

Maybe Spellcheck woud be of assistance.

A nice review ruined by so many errors in spelling , grammar ,etc.

I hope the book is better!

LP

A while back, a reader demanded to know why we didn’t publish negative comments. He was told that in fact we publish all signed comments, good and bad. Mr. Pugh’s comment is an example of once such negative comment.

Mr. Pugh is entirely correct and we thank him for his help. We found 20 errors in the text and they have been corrected. If there are more, let us know.

Yes, the book has a few typos as well. Fortunately, thanks to sharp readers, the errors in VeloceToday can be corrected.

A want ad is out for a good VeloceToday proofreader (which we dearly need). Unfortunately the pay scale begins and ends with O, the same as everyone else here at VeloceToday. Interested parties can apply to pete@velocetoday.com.

The Editor

Thanks for this – as ever – helpful review and overwiew of Intermeccanica history.

But one of your corrections has to be corrected itself. Some Cooper Formula juniors indeed were equipped with DKW engines in 1960/61 (see A-Z of Racing Cars by D. Hodges).

In Germany for example Kurt Kuhnke drove a Cooper-DKW (see for example here: http://www.formel3guide.com/images/ergebnisse/1960-solitude.pdf)

I hope to see the book soon maybe at Autobooks/Aerobooks. I met Mr. Reisner. I wish I could have talked to him longer–for instance, I would like to know if the book discusses how the Italia was originally planned for a lighter engine, hence the heavy Detroit iron causes front end problems. I was wondering if there is a ready made fix for this to make the Italia a more durable car. Ironically I once went to Santa Barbara to shoot a Daytona Spyder and an Italia that belonged to the same guy. I was astonished that the Italia sounded better and looked better! I also remember seeing a red Indra in Beverly Hills–does it say how many were made? I think these cars will be eventually as respected as Iso Grifos, it’s just that information on them before this book was so fragmentary….

Udo,

Thanks very much, and I stand corrected. Nor was I aware that the “Deke” was used in this manner. Reminds me that we do have a feature coming up on an Alfa engined Cooper one of these fine weeks.

The Editor

Nice fake cars

Oh they are real cars. They just aren’t a real Porsche 🙂

Oh yeah, there is a ’68 Intermeccanica Italia on ebay at this time. Very rough…

item=350400650848

Pete:

Great article matched with a great retort. A great leader once said “it isn’t the critic who counts.” I agree. Keep up the great work!