By Geoffrey Goldberg

We first met in 1990. I had driven a Jaguar E type up to the races at Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin, and its fresh motor needed its head retorqued. Wrenching in the paddock seemed reasonable, and it wasn’t long before a couple of guys wandered by. First was Gordon Barrett, who offered to help; we were joined by Harlan Schwartz, a character in his own right. This was the start of two new friendships, with these two remarkable men, who knew well of the affection for special cars, each having an 8C Alfa Romeo.

Gordon and I saw each other here and there over the next few decades. In 2007, at Pebble Beach, one of the judges was overheard in discussion with a friend, querying: “There is this one car in a class that is just head and tails above all the rest, but we don’t know the car….if it’s real, it’s a winner, but what if it’s a fake?” The class was for the pre-war Alfas, and the car in question was Gordon’s.

Over the years we shared notes on obscure Italian information, along with our mutual admiration for all things designed by Vittorio Jano. Gordon knew of the obscure story about Jano arriving at Alfa Romeo in the late 1920s, when Jano went into the test room, watched current staff testing an engine for durability. Reportedly, Jano stepped in as the new head of engineering, and he hung his bag on the throttle to keep it fully on and said “Now we go to lunch.” The story was known, but Gordon knew the source. He was steady that way.

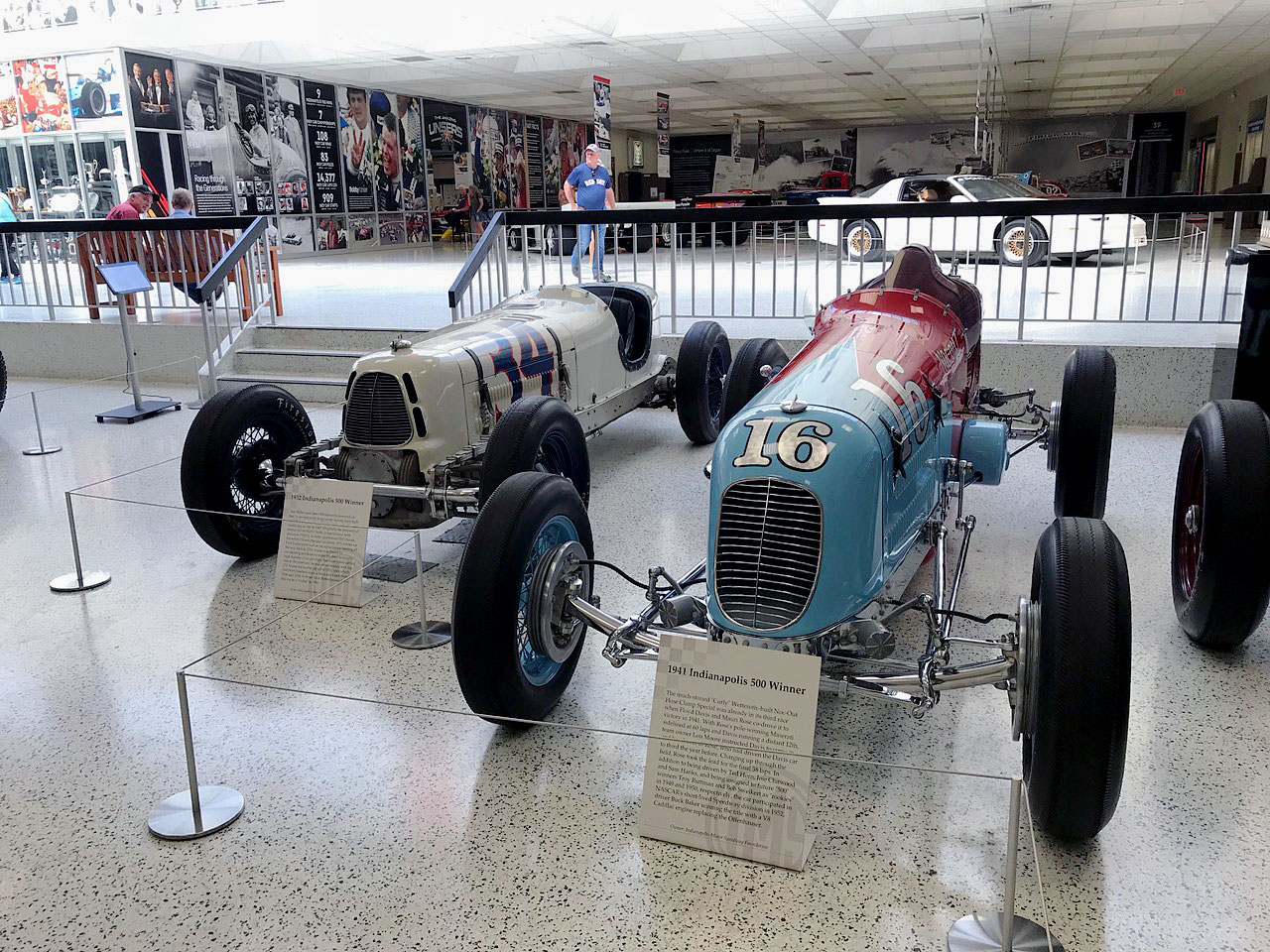

In 2018 I was home alone over the July holidays, and decided to go to Indianapolis and finally see the town and race track. Gordon said he would be around, was enthusiastic about getting together. We agreed to meet at the Indy Museum, and there we spent a couple of hours, looking at Offy engines, Lotus cars, and Indy cars from the 1960s-80s. Gordon explained how some were “altered” while running to go better – which some might have called cheating – but he explained that this was all part of the sport and that craft was measured by how skillfully were the efforts done. He told of designing interior fittings into the wings so that the wing profile could be modified after inspection without visible hardware. This was child’s play; the really good folks had much better tricks up their sleeves, and that Foyt was famous for his tricks.

Overwhelmed, I can’t remember most of what he told me, but what was clear was his combination of fabrication skills and love of the art in these cars. He told of his background: trained in engineering, he went to work for a couple of teams in fabricating the cars. In his words, knowing metal strength gave him an advantage over other people who were just making what worked.

He had started working for Grant King, and then got involved with AJ Watson, and while a true afficionado of American racing would have appreciated all these wonderful stories, try as I might, they fell on deaf ears. But we shared a love of Miller, Offy, tales of Leo Goosen and his engineering.

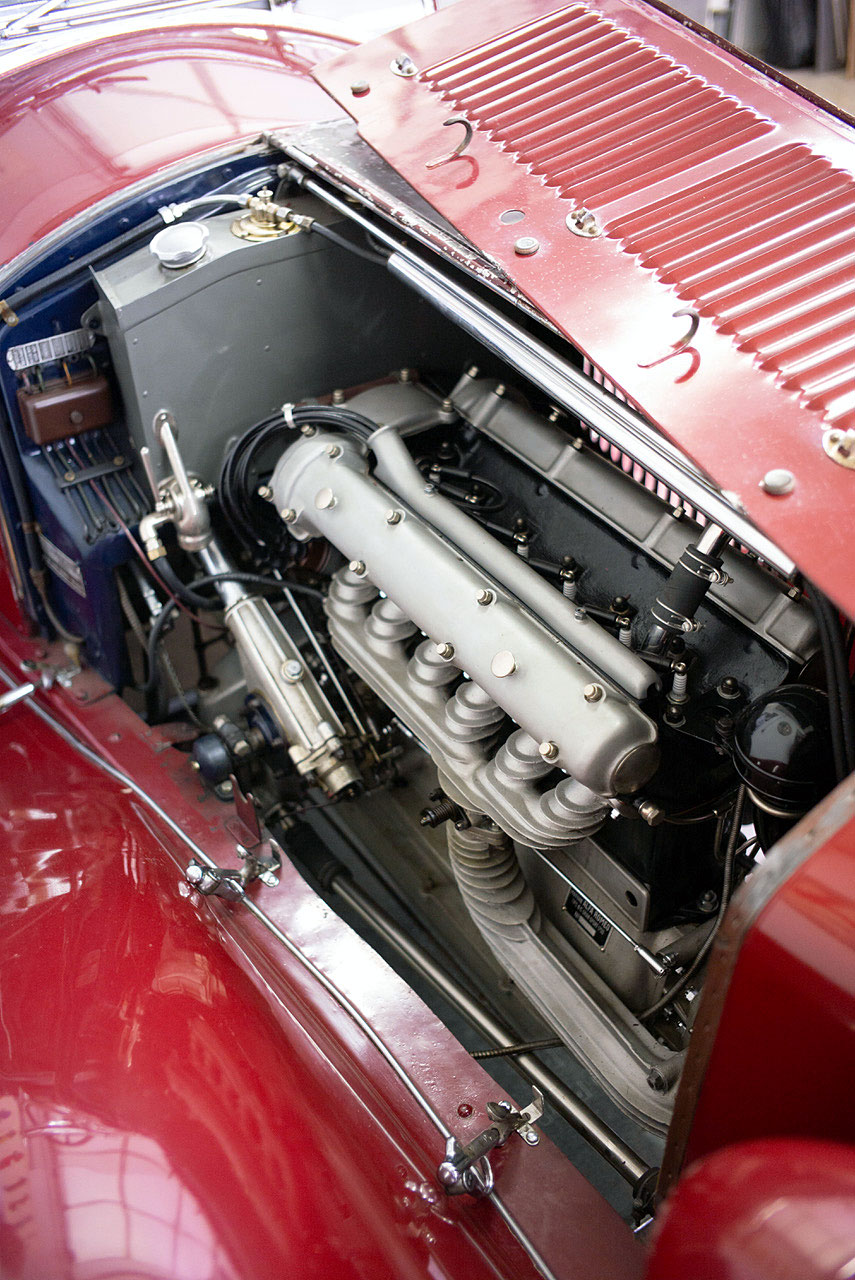

We went to his shop on Gasoline Alley. He explained that there were had been several Gasoline Alleys, relocated over time, but regardless of when or where, one hoped treasures were to be found. His shop was somewhere between a fabricator’s dream house and a man-cave par excellence. A few of his cars there – a Lola T70, a 6C Alfa 1750, and a lovely American hotrod creation from California, likely late 1950s. Each had their own stories – the Lola was somehow an intermediate version, with a special solution used mid-point in the chassis for a structural issue, of such interest that Eric Broadley came to visit and see the solution. The 6C Alfa had been Gordon’s car for decades. Its paint was glorious, at least 40 years old, possibly original (can’t recall), but the patina was as special as the car itself. You could live in that paint and be happy forever.

And the hotrod? Curious, it seemed odd but was a welcome part of the ensemble, with an elegance and simplicity, well done in California. It was the country cousin at the family gathering, the one with an odd sense of humor but a good twist afoot. Fit right in.

We spent the afternoon going through the shop. Regardless of how hard I looked, not a single speck of dirt was to be found. Anywhere. I checked each of the benches, the shelves, even old car parts. None, nowhere.

We went through the working shelves, each one a story. Every set of issues had their own shelf, organized somewhere between surgeon’s tools and a library par excellence. Clarity of thought and purpose was ever present.

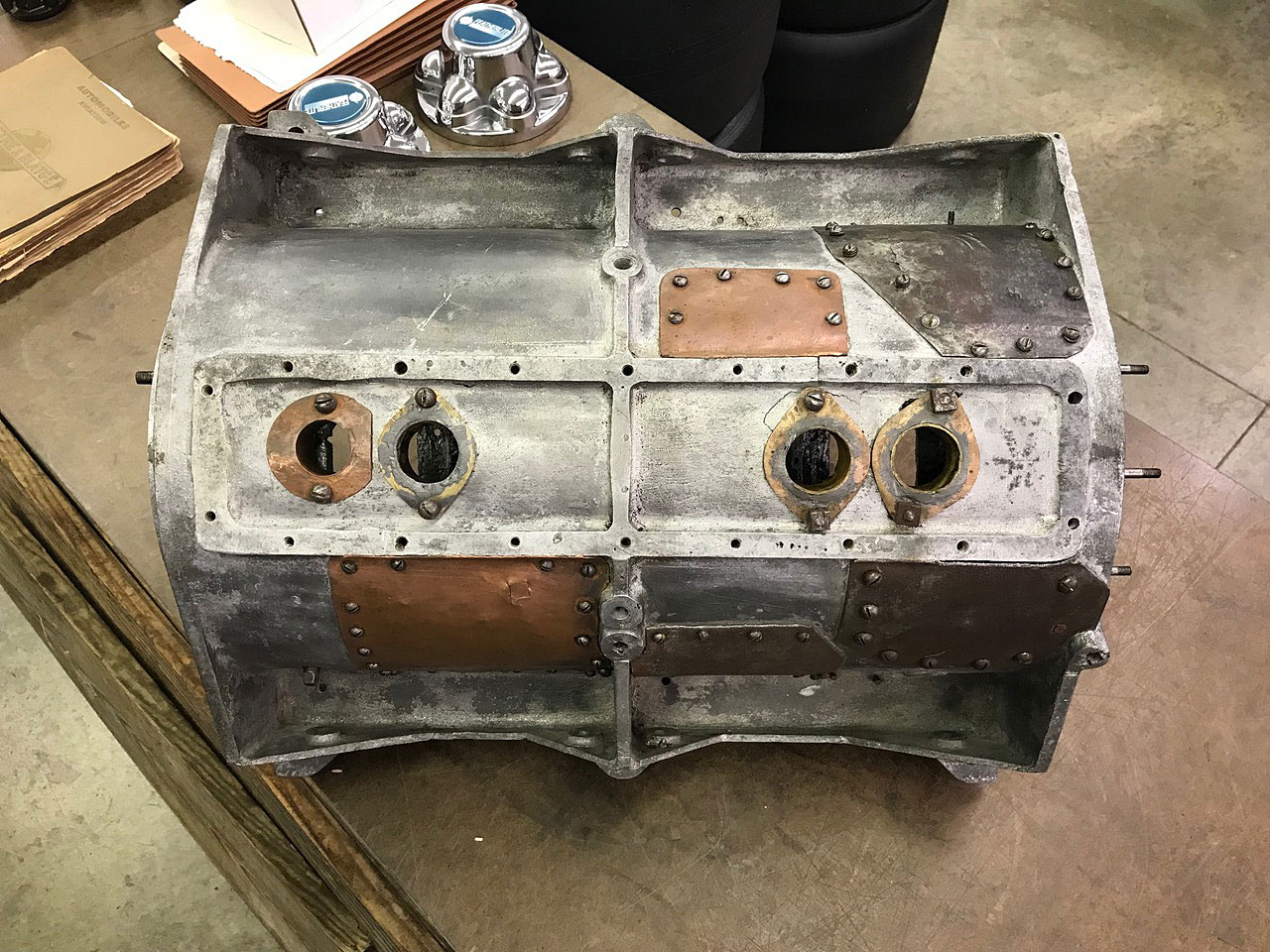

Multiple patches on the barrel crankcase of the 1914 Grand Prix Sunbeam engine. It was a copy of the 1913 DOHC Peugeot Grand Prix engine that revolutionized the racing engine.

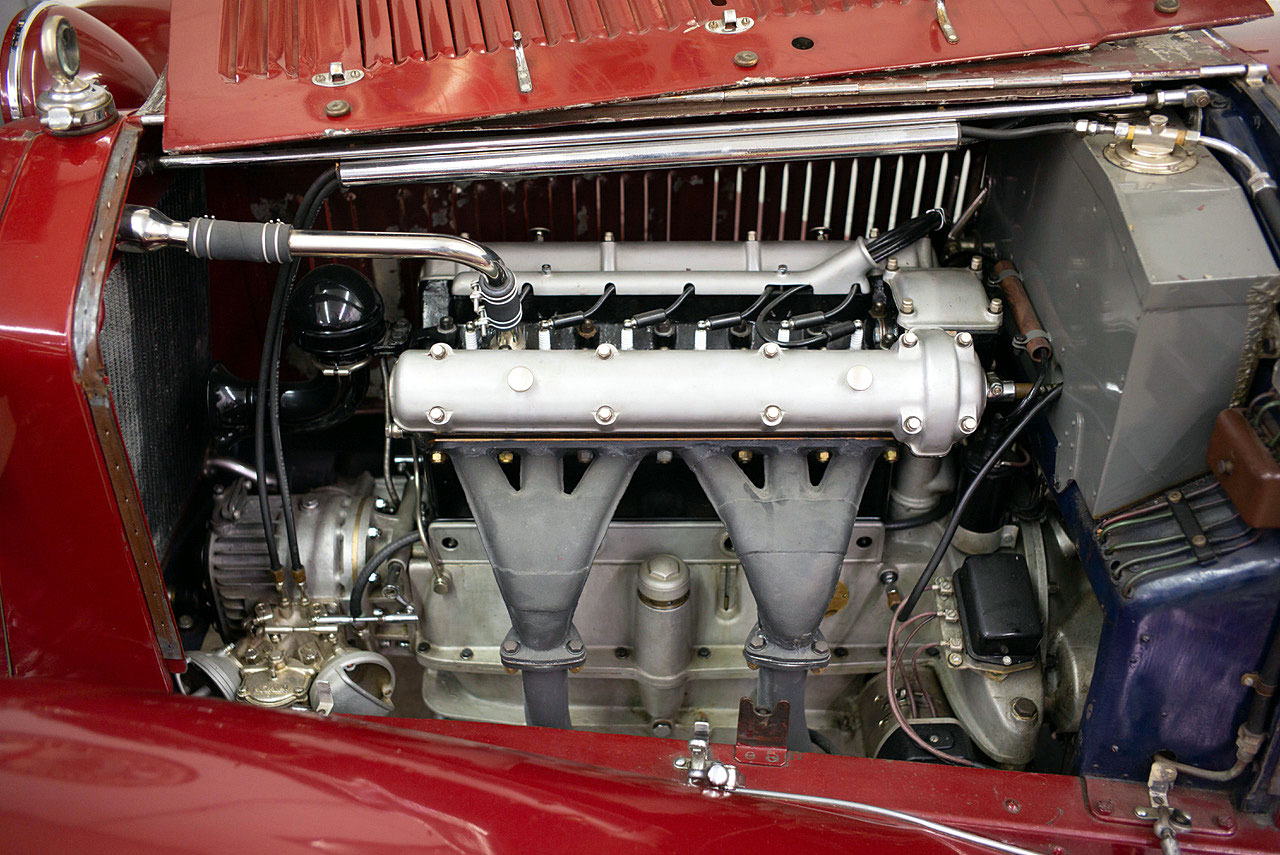

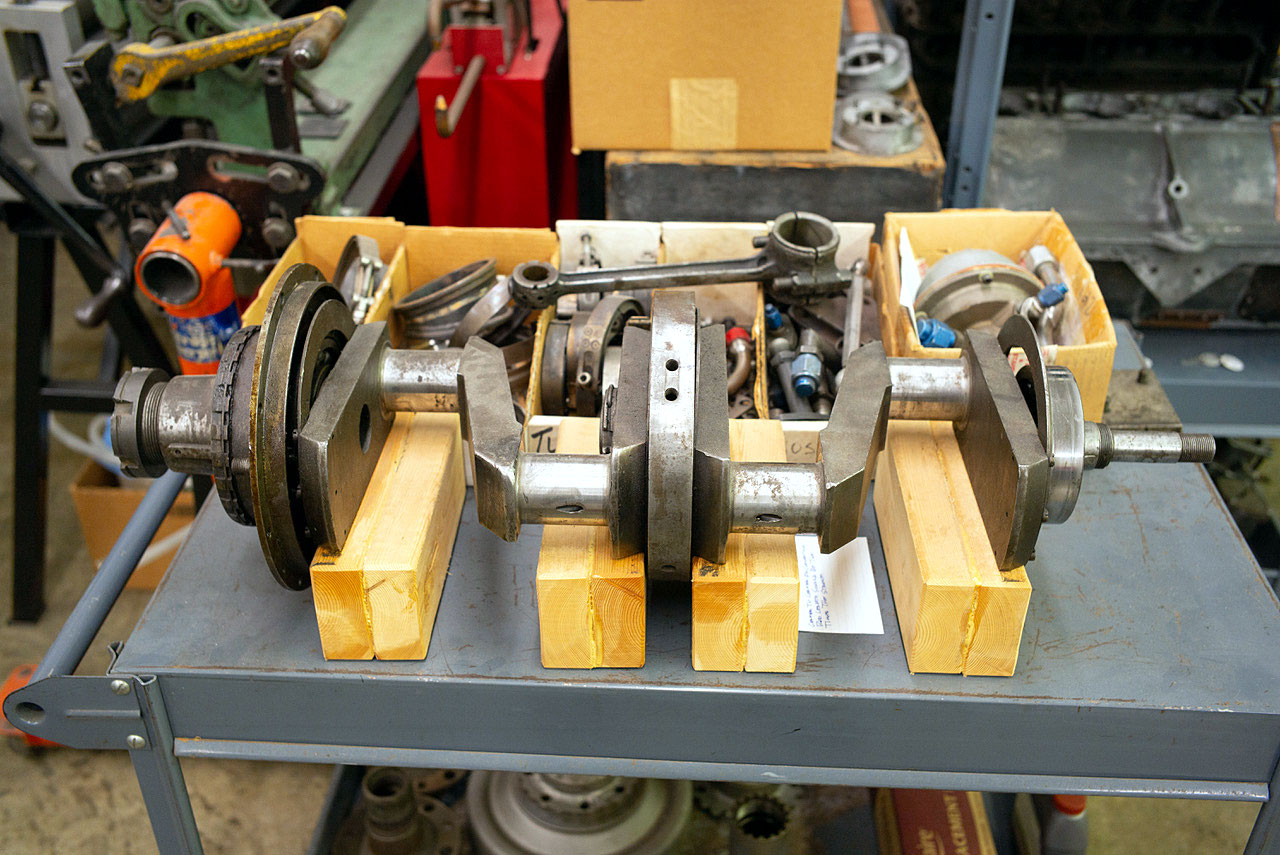

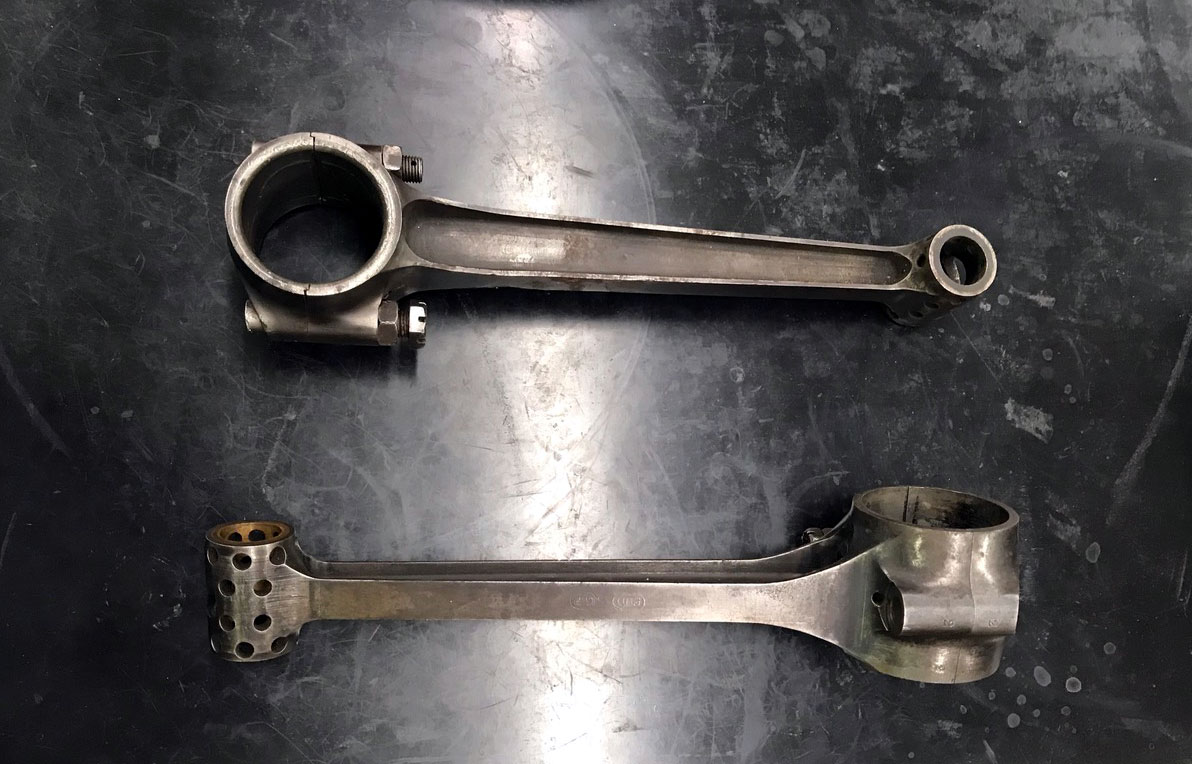

Of great interest was the Sunbeam engine from 1914. It was derived from the 1913 3-liter Peugeot Grand Prix engine by Henri, copied by Coatalen for Sunbeam in England. This race engine was of massive import, a four cylinder design, DOHC with four valves per cylinder. Gordon told the story of how Sunbeam “borrowed” one of the racing Peugeots following an event in England, which they then tore apart and copied. This particular engine had a deep history in several different car frames, and was even in a Mercedes long ago. Gordon said it had done Grand Prix racing, American oval and dirt tracks as well – and raced on them all. There had been much competition in getting this engine (there was a chassis too, no body), and he was proud to be in charge of putting this very special piece back together. We pondered its massive crankshaft, the overhead cams, the long connecting rods, and in particular, the engine crankcase. It had been much used, an incredible piece of history. Even the patches had patches.

We wandered through the parts shelves, and spent most of our time on the two Alfa shelves: one with memorabilia, Alfa bits and emblems. It was a bit of Milan in Indy. But it was the second shelf with the true goodies: the famous valve with the adjustment designed by Jano. The valve stem was intricately threaded with an upper and lower flat cap spun on; a special key tool separated them, which clicked through the adjustments to be done quickly and precisely. It only made sense when you could see it in person – and there it was.

Bookshelves were appropriately crowded, not just with Indy yearbooks, but even a full collection of Floyd Clymer manuals. Few have understood this very curious, passionate, under-appreciated man of post-war America, who was reprinting racing Maserati and Miller brochures in the 1950s! Gordon was pleased to have my Lancia book, which we discussed at length. He said it was a grand-slam, one not easily repeated or followed. He had always admired Lancias, but somehow hadn’t managed to get an Aurelia to join his Alfas. He wrote later about coming to visit and spend some time on Lancias, but sadly, it wasn’t to happen.

On the side shelves were a few vintage car models. In this more intimate space, we relished in this, a library of thoughtful things, of the character and charm of special older machinery. For a moment, it was the atmosphere most special, and the history surrounding us. Of course, it was all because of the person who cared for, assembled, and recognized all these things, but for the time, we simply absorbed all the surroundings.

Both of us were tired but unwilling to give up on the lovely day, and so we finally opted for dinner. Talking late into the night, discussion finally rolled around to his 8C Alfa, which was not in the shop. I told him the story from the concourse judge, which he understood immediately. He explained that the Alfa was largely unknown: it had been in the hands of a dentist he knew in a barn garage for about 30 years, from his youth near where he had lived in Pennsylvania. It was not on anyone’s radar, and with an additional decade or two of Gordon’s restoration, it was simply was new to the Alfa community. Gordon’s restoration had been meticulous, and he shared stories of visiting junkyards in Italy. In one he was able to find the correct pulley for the brake cables. Did anyone mention details?

Gordon explained he had done about eight Alfa rallies with the car, and he felt the car would only go downhill if he kept using it. He had just made the unusual and courageous decision to part with it. This was a strange decision for it was truly one of, if not the, best in the world. In true Gordon fashion, he made the move with finesse and total discretion: he traded it for a user 8C, one with perhaps a bit less charm, a bit less perfection, but broken-in and well-appreciated. He took the difference and put it into a retirement fund. He was to receive the replacement 8C within a few days, and was eager to see how he would enjoy it. It was an odd move, to be sure, but upon reflection, made a great deal of sense.

The visit and long day filled one full of joy. It was a delight to strengthen a friendship and spend the day with someone so knowledgeable, accessible and open. There are only a few special experiences one has in life that truly stand out as memorable, that make life worth living. This was one of them.

We touched base a few times after that, but it was hard to repeat the day without being there. I showed a close friend images of the shop – he was so moved that he wanted to approach Gordon about apprenticing for a week in his shop. These are things one should do. And it was only a matter of time before Gordon and I would reconvene, and we discussed his coming to visit. But it was not to be, as Gordon passed last year Amid the sadness of loss is a deeper and larger regret, one of not saying goodbye to this special person. May we all live our lives so fully and generously.

Pomeroy suggests another version of how the Peugeot was obtained:

“…whilst the Sunbeam cars which won the race were an interchangeable replica thereof, as the Sunbeam designer, L. Coatalen, bought one of the Peugeot cars through an intermediary and imported it to England as a model”. (p. 134); and also “The Sunbeam is of technical interest, in that the engine was an interchangeable replica (except of an enlargement of bore by 3mm. and stroke by 4mm) of the 1913 Coupe de l’Auto Peugeot, all the parts being copied from one of these cars purchased in France some months before the race.” (p. 37)

– from The Grand Prix Car, L. Pomerory, v. 1, 1954.