In previous chapters, Gijsbert-Paul Berk has described the background of the epic 1923 French Grand Prix. For the next few installments, he will describe a few of the major entrants, including Bugatti, Sunbeam, Fiat and below, Voisin. Ed.

In the early twenties Voisin was a relative newcomer in the auto industry. But Gabriel Voisin (1880 –1973) had already made his mark as an aviation pioneer and a creative designer of aircraft. From 1914 till the armistice in 1918, the Voisin factory in Issy-les-Moulineaux had become one of France’s major manufacturers of military aircraft.

It was more or less by chance he decided to switch to the production of automobiles. This happened because Ernest Artault and Louis Dufresne, the latter a former Panhard engineer, offered him the drawings and prototypes of a car they had designed at the request of André Citroën. Citroën had let Voisin know that he was no longer interested in the prototype of a luxurious automobile, as he intended to mass-produce a more popular and cheaper car. Citroën also disliked the sleeve valve engine based on the Knight principle. However, Gabriel Voisin liked the design and early in 1919 the first cars to bear the name Avions Voisin left the factory.

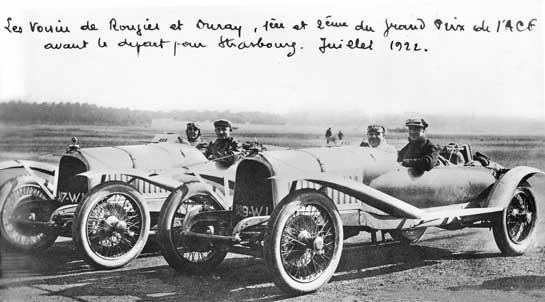

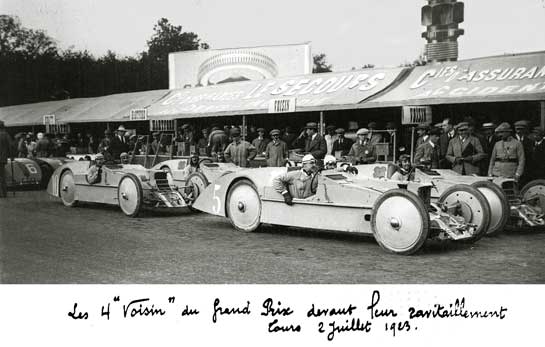

Voisin's C3S cars which took the first three places at the French Grand Prix de Tourisme in 1922. Note the bulges.

Voisin and his staff gradually improved their construction to comply with his own ideas and his knowledge and experience as an aircraft designer. This bore results. Within a few years Voisin cars earned a reputation for being smooth, safe and fast. Voisins also began to win in racing events. Their biggest success came in the 1922 Grand Prix de Tourisme de L’ACF in Strasbourg, where three C3 S models took the first three places. The cars had been built and prepared by the so called ‘Laboratoire’, the small research and development department that Gabriel Voisin had established for his factory in 1917. Its chief engineer was André Lefebvre, a young aviation engineer. (read book review)

The rules for the 1922 Grand Prix de Tourisme specified that the coachwork of the participating cars had to be at least 130 cm wide at the height of the front seats. Gabriel Voisin found this ridiculous and fitted his cars with an open four-seater body which was only 90 cm wide, but had 20 cm deep cigar-shaped bulges at both sides. This reduced the frontal area (air resistance) while still respecting the regulations. The race organizers had to accept his entries but were not pleased. As a result the rules for the 1923 Grand Prix prescribed specific dimensions for the touring car bodies, in order to avoid clever interpretations with the objective to reduce aerodynamic drag.

When these regulations were published by the ACF at the end of December 1922, Voisin exploded in anger, because his company was already preparing the same cars for the 1923 season, shaving away some kilograms here and there and changing the shape of the mudguards to improve their aerodynamics. He wrote a sarcastic ‘open’ letter to the ACF, denouncing its attitudes to progress in automobile design. In the same letter he announced that he would not start in the touring car race, but would instead engage four cars in the Grand Prix de Vitesse.

This impulsive reaction was of course complete ‘stupidity’, as Voisin would later confess in his autobiography Mes 1001 Voitures . Because the race was scheduled for the beginning of July, this gave them just five months to build four racing cars from scratch. Voisin did not even have a two-liter engine!

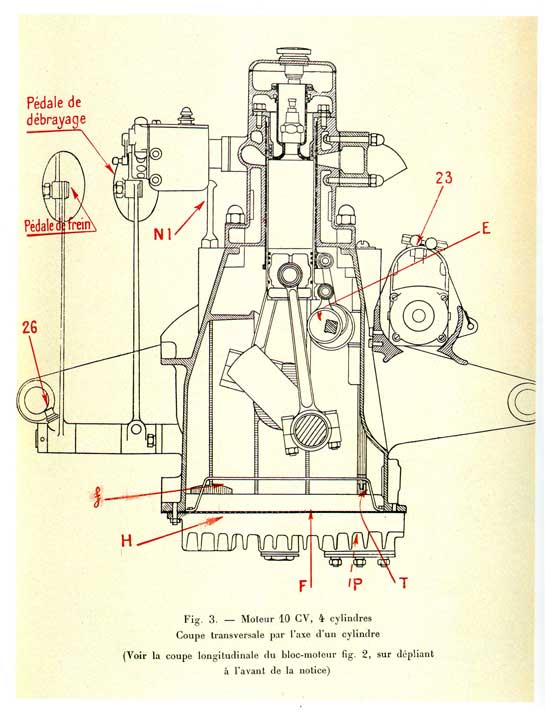

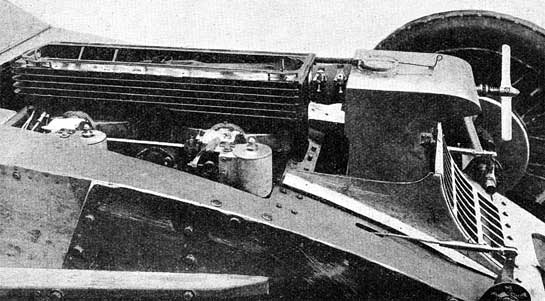

Fortunately Marius Bernard – his engine expert – was already working on a new 1,328 liter four-cylinder engine for the Voisin C4. It would have a bore of 62 mm and a stroke of 110 mm. Gabriel Voisin decided that by adding two cylinders, with the same bore and slightly reduced stroke, they could make a six-cylinder with a cubic capacity of exactly 1,984 liters. The trio of Voisin, Bernard and Lefebvre (who as project manager was responsible for the construction of the car) knew that their competitors – whose engines had poppet valves and overhead camshafts – could count on higher revs and thus more power than their own sleeve valve machines could deliver. The only way to compensate for this handicap was to reduce to a minimum both the weight and aerodynamic drag of their racers. Voisin and Lefebvre – both experienced aircraft designers – used every trick in their book.

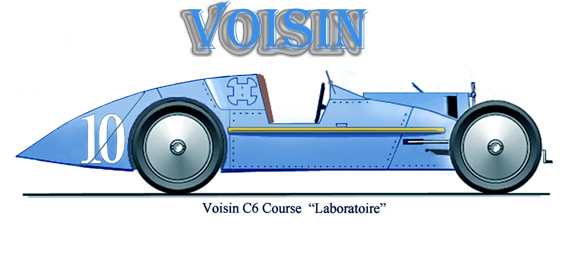

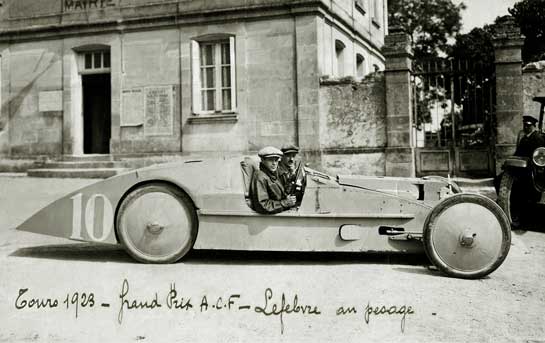

The C6 Course or ‘Laboratoire,’ as it later became known, was designed like the fuselage of an airplane. It had no conventional chassis, but was in fact one of the earliest racing cars with a monocoque construction; a box made up from a light ash frame, covered with aluminum panels and a flat aluminum under shield. This structure, with some steel and wooden reinforcements, supported all the mechanical parts such as the engine, transmission and front and rear suspensions. Its width was dictated by the requirement that the cockpit should offer enough space for the driver and a riding mechanic. The tail was long and tapered with the rear wheels inboard, within the contours of the coachwork. The whole body looked somewhat like an aircraft without wings and the layout with its narrow rear track resembled more that of a Morgan three-wheeler than of a modern – by 1923 standards – racing car.

After a lot of experimenting, Lefebvre found that a rear track of 75 cm combined with a front track to 145 cm provided sufficient stability and since the car still handled well in corners, he could save weight by leaving out the differential gears. The rear axle housing, containing only the crown and pinion wheel, was made from aluminum and was suspended on two quarter elliptic leaf springs. The front axle rested on half elliptic leaf springs and also had large friction shock absorbers.

Diagram of the four-cylinder Voisin engine, identical in cross section to the six-cylinder which powered the Voisin C6.

Lefebvre and his mécanos worked day and night to get four cars ready for the race, systematically testing and improving every detail. They mounted magnesium pistons and provisions were made to keep the temperature of the cylinder heads down and to prevent the sleeve valves from seizing, even if this meant greater tolerances and therefore an increase of oil consumption. Engine cooling was a thermo-syphon system aided by a small water pump driven by a tiny air propeller above the radiator. Bench testing showed that, with the two big Zenith 36 HK carburetors, some 80 bhp was available at 4800 rpm.

However, Gabriel Voisin instructed the drivers not to exceed 4000 rpm, which limited maximum power to 75 bhp, resulting in a top speed of just under 175 km/h. Not bad at all – but not enough! The Voisin were outclassed from the start by the limited power of their engines. Voisin must have realized this during the practice sessions, but he did not for one minute consider withdrawing his entry. That would have been unlike him. It seems that Gabriel Voisin was rather pleased with the achievement of André Lefebvre, his chief engineer and ‘spiritual son’. In his memoirs he wrote: “Thirteen of our competitors, some of them the greatest names in the world of speed, had bitten the dust and we were amongst the survivors.”

With hindsight, it becomes clear that the 1923 ‘Laboratoires’ were in many details a try-out for a next generation of touring sports cars that Gabriel Voisin had in mind for the 1924 Grand Prix the Tourisme.

Thanks for a very insightful read on the fabulous Voisin that were entered in the French GP. Many years ago while building a die cast aluminum model of the Laboratories I asked Peter Helck about the racer. He immediately responded telling me that one could tell from quite a distance that it was a Voisin coming due to the plume of smoke following it. He was there for the race with his new bride Pricilla in France.

Stan Smith

In the following reprinted article on building a replica, the fan ‘to assist cooling’ is specified as a propeller (impeller?) to drive the water pump. I suppose that does assist cooling