Story by Nicholas Lancaster

Photos by Paul Gregory

Historic photo courtesy Automobili Storico Alfa Romeo

Shortly after the introduction of the totally new Alfa Romeo Giulietta Sprint in 1954, the directors at Portello took the decision to develop the Sprint as a competition car. It was certainly a good place to start. The basic Giulietta Sprint had been designed by the same technicians responsible for the racing program, and it showed. For the mid-50’s the Giulietta was technically advanced, with a high-revving twin camshaft engine constructed out of aluminum alloy and the gearbox and differential casing made from the same material. The suspension was conventional but well thought out: independent at the front with unequal-length A-arms, coil springs and an anti-roll bar; at the rear there was a well located live axle with single lower trailing arms and coil springs, while a tubular A-bracket linked the top of the axle casing with the floor pan, ensuring excellent location. The brakes—large finned drums—were excellent for that period, while the fact that the Sprint looked terrific didn’t hurt either.

Although the Sprint wasn’t originally conceived as a racing car, its advanced specification and fine performance had persuaded many Italian drivers that it would be well suited to the 1300 cc class in GT racing, which was growing rapidly in popularity at that time. In national events both standard and modified Sprints had enjoyed some success but at the international level the limitations of the standard Sprint were soon exposed, most often by the arch enemy, Porsche. In the spring of 1955 several Sprints appeared for the 22nd running of the Mille Miglia, but all were forced to give best to the Porsche team, which stormed to victory in the 1300 GT class, leaving the first of the Sprints trailing home in third place. So the target was obvious; all Alfa Romeo had to do was hit the bulls eye.

Development

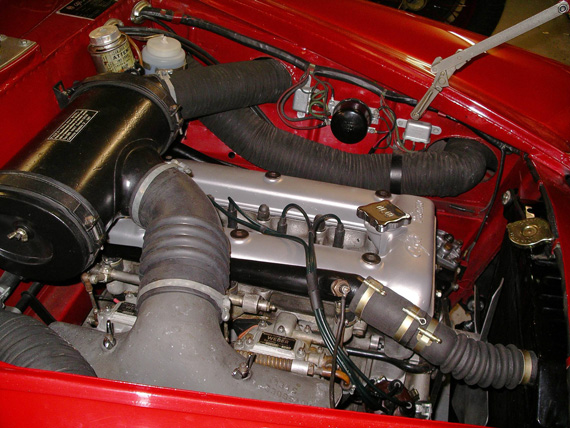

Engine development was in the capable hands of Giuseppe Busso and his department and their work is obvious as soon as you lift the bonnet. Behind the grille an intake nozzle—used for cockpit ventilation on the Sprint ‘normale’—was modified to duct air through a large diameter flexible tube to a cast aluminum collector box on the intake side of the engine, via an air filter mounted on the firewall.

This immaculate and correct Sprint Veloce is owned by the photographer, Paul Gregory. Note the unusual air intake system feeding the dual Webers.

This was a development of a similar system, used on the final version of the ‘Alfetta’ grand prix car, and credited with boosting the 159’s output by 25 bhp.

A Bendix electrically driven fuel pump replaced the engine-driven mechanical unit of the standard Sprint, supplying a pair of Weber 40DCO3 side draught carburettors. The cylinder head ports were cleaned and polished, while the compression ratio was raised from 8.0:1 to 9.1:1. High lift camshafts were part of the package and the conrods were shot peened. A new tubular exhaust manifold coped with the increased gas flow while down below, an elaborately baffled cast aluminum sump, with built-in oil cooler, replaced the standard Sprint’s steel pressing. Assembled with tremendous care and attention to detail, the modifications resulted in the overall output being raised from 65 to 90 bhp (DIN) at 6000 rpm, with torque improving to 86.5 ft-lbs at 4500 rpm, up from 79.5 at 4000 rpm.

The Sprint Veloces, particularly the early 750 series cars such as this one, used a variety of ways to save weight; note the missing glove box lid.

The modified engine was fuelled from a tank increased in size from 53 to 80 litres, a decided benefit for endurance racing, while a stronger clutch mated with a modified gearbox that placed the gear lever on the floor, rather than on the steering column. The final drive ratio was raised from 9:41 to 10:41 providing 18.6 mph per 1000 rpm compared to the standard Sprint’s 15.7 at the same revs in top gear.

Placing the gear lever on the floor was welcomed by most critics, although not everyone seems to have been happy about the change. Gregor Grant road-tested a standard Sprint for “Autosport” in 1955, and the column gearshift was his main criticism in an otherwise enthusiastic review—yet a year later, in his report on the 1956 Mille Miglia, he recounts how Sprint Veloce drivers considered the revised method of changing gear slower than the standard Sprint’s “waggle stick” on the steering column!

In addition to these wide-ranging mechanical improvements, the first 600 Sprint Veloces were extensively lightened. The steel bonnet, boot lid and doors were all replaced by aluminum, as were the bumpers. The rear screen and the side windows were replaced by perspex, while sliding side windows eliminated the weightier roll-up mechanisms of the standard Sprint. Inside, the replacement side windows also freed up more elbow room for the driver and passenger, and lightweight competition style seats provided them with greater lateral support.

There has been some debate over the amount of weight actually saved by this process. Suffice to say that both Anselmi and Alfieri quote the following: the standard 750B series Sprint came in at 850 kg while the 750E Sprint Veloce weighed in at 780, a worthwhile saving of 70 kgs. Interestingly, the later 101 series Sprint weighed in at 880 kg, while the 101.5 Sprint Veloce—now equipped with the standard steel body, and the same specification windows and bumpers as the Sprint ‘normale’—came in at 895 kg, a slight increase, presumably reflecting the greater weight of the modified engine and it’s ancillaries.

Later cars also had small seats molded into the tiny space behind the front seats. The space worked better as luggage room.

Externally there was very little difference to the appearance, the main give-away being the sliding side windows on the Sprint Veloce, while the new model carried the script “Giulietta Sprint Veloce” along the front wings, along with the Bertone motif which honored the constructor of the Sprint bodies.

The new model proved popular from the start, both for track use and as an uncompromising road car. This was despite a sizeable increase in price over that of the Sprint ‘normale’. While the Sprint was offered at 1,735,000 lire, the Sprint Veloce commanded 2,050,000, a healthy premium. Most buyers probably reckoned this to be quite reasonable considering the amount of work that had been carried out and the extra performance. The sales figures seem to bear this out. First going on sale in April 1956, just in time for the Mille Miglia, 252 Sprint Veloces found buyers that year, whilst a further 458 were produced in 1957.

On The Road

“Auto Italiana” tested a Sprint Veloce over 4200 kilometres in early 1957. They considered the Sprint Veloce “so different to the standard Sprint that it might almost have been another car altogether”. Recording a standing kilometre time of 31 4/10 seconds, they concluded that the Sprint Veloce was “an almost unbeatable car…. and this is demonstrated by the number of victories it has scored on the track.”

The 750 series body with the smaller headlights, grille and taillights, was cleaner, more delicate and simply more satisfying than that of the 101 cars.

In February 1957, Jesse Alexander tested a privately owned example for “Sports Car Illustrated” (now Car and Driver). Better known nowadays for his fine motor sports photography, Alexander was the European correspondent for the magazine, and had taken to the Continental scene like a duck to water. He got the point of the Sprint Veloce at once, pointing out that “whilst the Sprint is a fine, high speed, touring-sports car…. the Sprint Veloce is considerably more than this. The car was literally born in the mountains of Italy—on the Radicofani, the Futa and the Raticosa mountain passes which make up the most rugged part of the Mille Miglia.” He concluded: “ ….here is a true Italian competition machine with just enough comfort and flexibility left in the design to make it a really outstanding piece of equipment.”

Into Battle

The Sprint Veloce’s first appearance in competition was comparatively low key—a Sprint Veloce driven by Ignazio Scaletta appeared at the Coppa della Consuma hill climb on 25 April 1956. Scaletta finished in second place in the 1300 GT class, following home Odoardo Govoni in a modified Sprint ‘Normale’. Govoni was an accomplished hill climb competitor who later won rounds of the European Hillclimb Championship, so this was no disgrace, but a few days later there would be a different tale to tell. It was time for the 23rd running of the Mille Miglia.

Alfa Romeo always took this incredible race very seriously indeed. Journalist Henry Manney competed in the 1957 event at the wheel of his own Sprint Veloce, and later related his adventures in “Road & Track” magazine. As an example of the Alfa Romeo attention to detail, Manney recalled that as he approached the famous starting ramp in Brescia shortly before his start time, a team of Alfa Romeo works mechanics suddenly descended on his car. Tires were inspected, the bonnet opened and various leads and fluid levels checked, before the bonnet was slammed shut and he was urged on his way, the mechanics then waiting impatiently for the next Alfa Romeo in line. They were kept busy, because in both 1956 and in the following year, the entry list contained a healthy proportion of 1900s and Giuliettas. Amongst the 1956 entry, six of the Giuliettas were specially prepared by the works—Alfa Romeo might no longer be involved in front-line racing but they were certainly very serious about giving the Sprint Veloce a successful debut.

Making their mark

The race was won overall by Castellotti’s Ferrari in dreadful conditions that left many entrants stranded at the roadside with extensively damaged vehicles. Through the carnage came the Sprint Veloce of Sgorbati and Zanelli to take eleventh place overall and first in class, ahead of much more powerful opposition. Indeed, the top ten contained five Ferraris, four Mercedes 300 SLs and a lone 1500 cc Osca in ninth. The best Porsche 356 came in almost half an hour after Sgorbati, and it was a 1600 cc version at that! The Sprint Veloce had made its mark.

During the rest of the year, Sprint Veloces stormed to class victories in such diverse events as the Tour of Sicily and the 1000 Kilometres of the Nurburgring, where Jo Bonnier and Herbert MacKay-Fraser led home an Alfa Romeo parade with Sprint Veloces filling the first six places in the 1300 GT class. In a strong field, Bonnier and MacKay-Fraser didn’t just trounce the 1300 class Porsches, they also lead home the 1600 cc examples as well!

To ensure this level of success, Alfa Romeo did more than just build the cars and offer special preparation for selected clients. To get the best out of the equipment there was help on hand from chief test driver Consalvo Sanesi. Sprint Veloce driver, Egidio Gorza, lapped Monza with Sanesi at his side. The veteran test driver was keen to point out that the Sprint Veloce was capable of taking the daunting ‘Curva Grande’ flat out in fourth gear. Gorza was not convinced, but he managed to persuade himself to give it a go. To his relief he found that Sanesi was right and that the car stayed glued to the track. It was a lesson well learnt as Gorza went on to win both the Italian 1300 GT Championship and the Italian 1300 Mountain Trophy that year.

Along the way, he put in another typical giant-killing performance with his Sprint Veloce in the Coppa delle Dolomiti. This was a unique event notable for a 300 kilometre course that ran up, down and around the wonderful scenery of the Dolomites near the famous village of Cortina d’Ampezzo. The race was particularly difficult with steep climbs and dauntingly fast downhill bends. The road conditions were poor and dust was usually a problem. The weather was often an added difficulty with poor visibility and even snow falling on occasion. This was unusual terrain for a motor race and meant that victory didn’t always go to the fastest, most powerful machinery. In 1956 the overall winner was Giulio Cabianca in an Osca Mt 4 1500, averaging just over 62 mph. He came in ahead of Olivier Gendebien in a 3490 cc Ferrari 290MM. The first GT car home was a Ferrari 250 GT ahead of Gorza’s Sprint Veloce, the little Alfa snapping at the powerful Ferrari’s heels. At least two Mercedes 300 SLs followed Gorza home. Yet again, the nimble handing of the Sprint Veloce had proved ideal for the event, boding well for high placings over similar mountainous terrain in events such as the Alpine Rally. Sure enough, in 1957 a Sprint Veloce triumphed in the Austrian Alpine Rally with Bauer and Zannini coming in first overall, while on the Tour de Corse, around the twists and turns of the Island of Corsica, Nicol and de Lageneste claimed another first place outright.

Overall 1957 proved to be another excellent year for the Sprint Veloce. Once again there was a class victory on the Mille Miglia. This time the French team of Martin and Convert lead home the Giulietta charge in 20th place overall after the previous year’s winner, Sgorbatti, had gone off the road just when he looked to be heading for a repeat of the previous year’s victory. At the Nurburgring, Mahle and Graf lead home another train of Giuliettas whilst up-and-coming Swedish star, Jo Bonnier, took class wins in several events and Gorza and Morolli took a class win in the Rheims 12 Hours. However, at International level the writing was already on the wall.

As early as September 1956, the Sprint Veloce drivers competing in the Coppa Intereuropa at Monza had been given a glimpse of the future, courtesy of Massimo Leto Di Priolo. Driving a Zagato bodied Sprint Veloce, Leto di Priolo won the class, comfortably beating Bonnier and Gorza. From that moment on, the Zagato SV became the car to beat.

Still, the Sprint Veloce success story wasn’t quite over yet. In the United States, Van Beuren and Velasquez won the 1300 GT class in the 12 Hours of Sebring in early 1958, whilst on home territory Sprint Veloces scored fine class wins in the Giro di Sicilia and the Targa Florio, but generally, the lightweight Zagato bodied coupes were taking over at the top of the class.

Later on in the “veloce” saga, there appeared the name “Conrero”. Many stories circulated about cylinder blocks especially cast to raise compression, and other anomalies between these cars and the cars from the Alfa factory. I believe there may have been some races protested, and Conreros disqualified .- Don Falk

real cars racing. would that it were so today…

Conrero was a tuner that also made kits for Opel Kadett. Has no affiliation with Alfa Romeo.

Interesting article from Nick – I bought my, very used, Series 750 Sprint Veloce in 1965 from Dan Marguilies, a purveyor of ‘interesting’ cars based in West London. Registration number was WYL 71- is it still around? I’d love to know. Mine was LHD and had detail differences from the immaculate car featured in the article. The top of the dash/instrument panel was matt black as was the ‘luggage platform’ behind the seats. A standard Alfa Romeo ‘plastic’ steering wheel was fitted as was the lid to the glove box and the seats were faced in red leather. The car had been used in competition of some form although we were unable to establish exactly what. I loved the car to distraction but she had to be sold to fiance marriage – not unusual I suspect. I have been an Alfisti ever since.