By Pete Vack

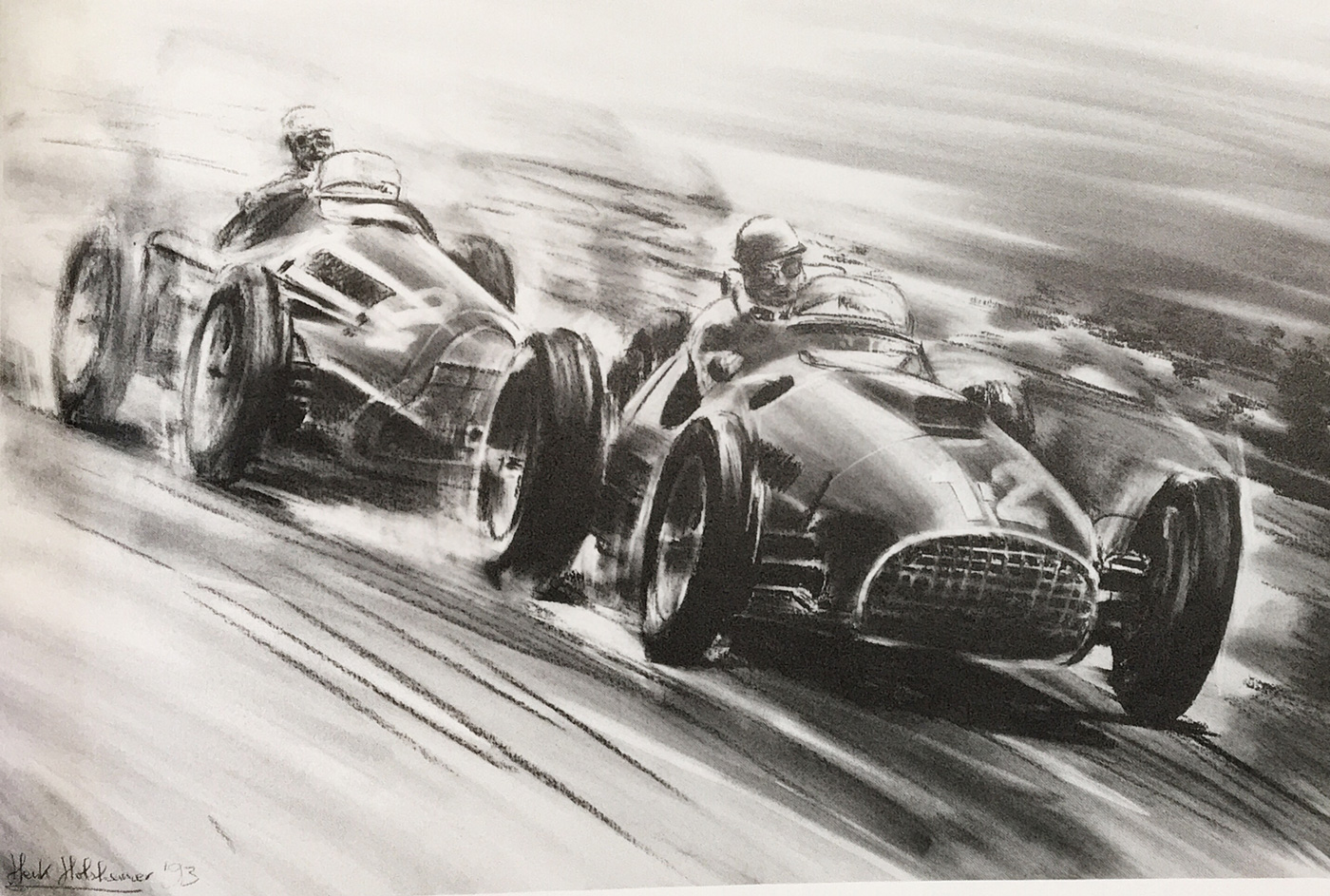

All drawings by Bert or Henk Holsheimer

In the Foreword to L.J.K. Setright’s The Designers (Follet, 1976), Raymond Baxter* wrote of Setright, “His dress, manner and conversation have a certain studied elegance not common amongst technical writers since the passing of such as Laurence Pomeroy…Setright is as much interested by the men who designed them as by their machines.”

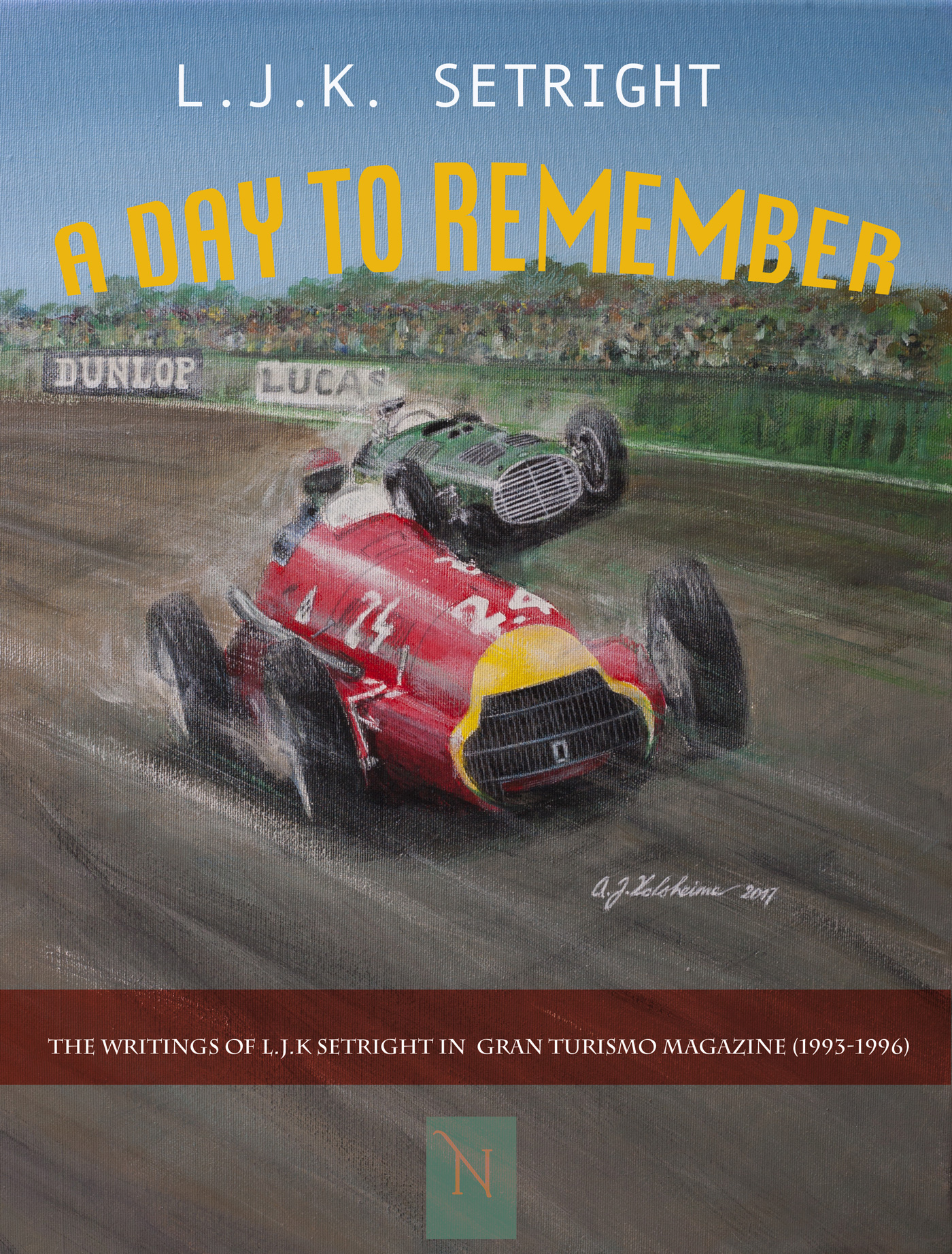

Gerrit Brand, who published the book A Day to Remember, a compilation of ten of Setright’s columns written for GranTurismo magazine (and reviewed herein), noted that Setright’s writing style wasn’t for everyone. “It was very erudite and considered to be slightly over the top by some.”

He liked to use Latin, for example. A foreword was not simply a foreword, but an Exordium (Latin, from exordiri to begin, from ex- + ordiri to begin). He used the phrase, Post hoc ergo propter hoc (Latin: “after this, therefore because of this”) in reference to Ferdinand Porsche’s being a theoretician vs an artist (Designers page 40). He was often long winded and, in the process, perhaps a bit condescending.

An acquired taste

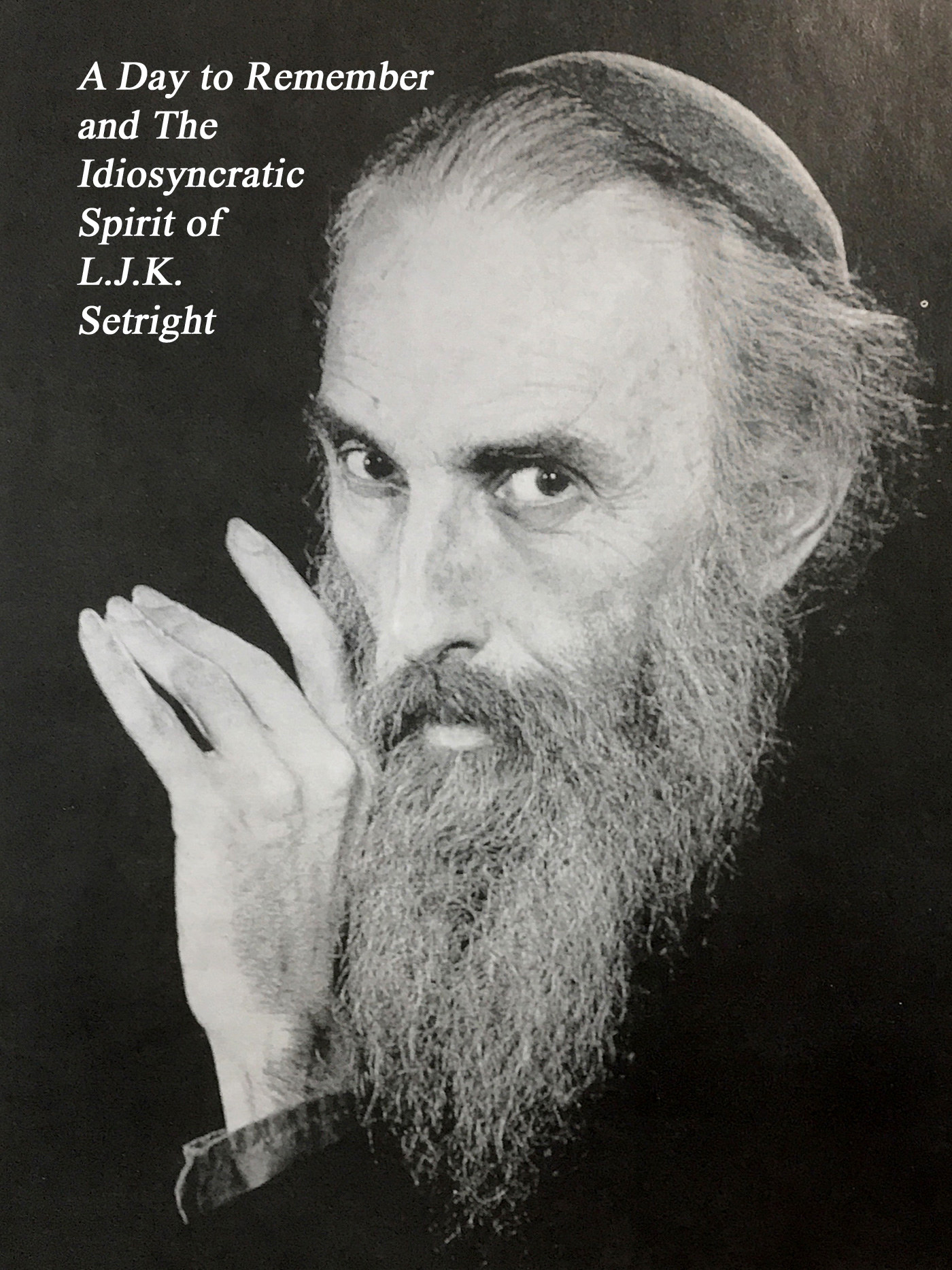

As nearly everyone agreed, Leonard John Kensell Setright (August 10, 1931, London – September 7, 2005, Surbiton) is an acquired taste. For those of you not familiar with his work, from 1960 to 1995 Setright authored as many as 19 books on aircraft, motorcycles and cars, and wrote columns for many magazines from CAR in the UK to GranTurismo in Holland. He could be satirical, sartorial, very insightful and often biased. He loved Bristols and Hondas, and drove both regularly. Setright was also known for his love of smoking Sobranie Black Russian cigarettes. He was described as resembling “a gaunt Old Testament prophet in Savile Row clothes”.

Setright’s father was an engineer, credited with inventing a ticket machine used on buses. A practicing Jew and a scholar of Judaism, Setright studied law at the University College in London. According to Wiki, he hated the legal profession and at the age of 29 he decided to concentrate on writing, primarily as a motoring journalist.

Criticisms

In 1968 W.W. Norton published Setright’s The Grand Prix Car, 1954-1966, which was met with mixed reviews. Nevertheless, this Pomeroy follow-up helped established Setright as a serious and knowledgeable writer with a good handle on both history and technical issues.

Naturally Setright had his critics. Karl Ludvigsen noted that “… the author’s open and sincere devotion to his Jewish faith [negatively] influenced his views about the men [particularly Dr. Porsche] and institutions that were part and parcel of the appalling atrocities committed under Adolf Hitler.” ** Automotive journalist Gijsbert-Paul Berk, who was the editor of the Dutch magazine AutoVisie in the 1950s, (and roughly the same age) doubts that Setright’s Jewish ancestry had much to do with his opinions, particularly of Dr. Porsche’s swing axle. “Setright could be unkind, but was he wrong?”***

A Day to Remember

Gerrit Brand connected with Setright’s enthusiasm for Italian cars. “It was a pleasure to publish contributions by L.J.K. Setright in my magazine. I’m not sure if all of our readers at the time appreciated Setright’s complicated writing as much as I did…Setright’s texts are very much like good wine or cigars, the older they get the better they become.”

In his first column for GranTurismo, (and the first chapter in the book A Day to Remember) Setright wistfully recalled the Grand Prix of Great Britain at Silverstone in 1951, when Gonzales and Ferrari finally put another nail in the coffin of the Alfetta 158/159. He was only 20 at the time, still capable of awe without judgement. He went to the race with his brother, driving an old, open Lea-Francis.

The pieces written for GranTurismo were generally supposed to address some manner of Grand Touring and the ensuing pieces did just that. Perhaps Setright was at his best writing columns; short, focused articles that rarely allowed him to ramble or preach.

Setright postulates that the beginning of the GT phenomenon might have originated as wealthy patrons wanted to drive from Paris to Nice as rapidly as possible. This in turn led to a great deal of press interest and the records continued to fall as Hispano-Suiza, Voisin, Citroen and Hotchkiss entered the fray. He writes “It was in this tradition that France produced such a wealth of beautified and fast cars, elegant both in looks and in behavior, bearing the badges of Delage, Delahaye, Hotchkiss or Talbot.”

The Italians, of course, had the kind of terrain that encouraged the same type of automotive development, and early on in the Mille Miglia there were fast, closed cars that made driving much easier.

In a chapter on the Mille Miglia, Setright notes that while the Italians won every Mille Miglia apart from Mercedes Benz victories in 1930 and 1955, the French, noted for their fast road cars, were “conspicuously absent.” There is a problem here as this would come as a surprise to the Delahaye team that finished in 4th and 7th positions overall in the 1939 race, and not only were the French present, but Dyna Panhard and Renault dominated their 750 cc classes in the post war events.

GranTurismo inspired cars would also be used to race trains. In “Beating the Train”, Setright tells us it was an Englishman, one Dudley Noble, who first thought of racing the Blue Train from Calais to Cannes. “The Blue Train was one of the crack French expresses, at a time when the French Rivera was the winter goal of Society’s elite,” wrote Setright, noting that the gentrified British would take the ferry from Dover to Calais, and embark upon the Blue Train to arrive in the south of France in 24 hours. Could a car beat this time? In 1930, after the first attempt ended in failure, Noble’s Rover Six eventually beat the Blue Train at least in part, and set off a train of copycat attempts; perhaps the most famous was Woolf Barnato’s successful race with a beautiful Bentley with fastback Gurney-Nutting coachwork. GranTurismo indeed.

Setright had an uncanny ability to weave into his texts the merits of Bristol to the point where one wondered if Tony Crook was slipping him money under the table. A longtime aircraft enthusiast, Setright liked to expound upon the various interfaces between the aircraft industry and the automotive industry. Although many firms, such as Alfa Romeo, Mercedes-Benz, SAAB, Rolls-Royce and Armstrong-Siddeley, to name a few, were companies that also engaged in the development and manufacture of aircraft and engines, the innovations and precision known on the aircraft side of the companies rarely transferred over to the automotive branch. “…quite simply, car manufacturers were generally in business to make a profit from products that were no better than they had to be.”

Enter, of course, Bristol, whose cars, according to Setright, were manufactured and inspected to aircraft-industry standards; even saloons were wind tested and aerodynamics were adapted from lessons learned in the aircraft side of the house. Of course, such things were also relatively common among the other manufacturers but perhaps it was Bristol who did a better PR job.

Reading Setright is an experience in itself. Like our own Ken Purdy, he ponders, he speculates, he ruminates, he lectures; he often makes mistakes, forgets things along the way (when he was writing, there was no Internet to quickly check facts), but is always entertaining and never dull, and perhaps most importantly, makes one think.

Hardcover with dustjacket, 116 pages ISBN 9789491737305 Euro 19.95

Contact Gerrit Brand at info@nobleman.nl

Order here: http://www.nobelman.nl/ljk-setright.html

_________________________________________________________________

*Raymond Baxter was a noted BBC commentator and race driver. He was also famous for providing radio commentary on the funeral of King George VI in 1952 given while suspended from the ceiling of Westminster Abbey!

**While Setright’s bias might be understandable, Karl Ludvigsen noted in an article for the British 911 & Porsche World that in the book Drive On! — A Social History of the Motor Car, published in 2002 by Palawa Press, Setright was unduly critical of German automotive figures. “Auto-industry figures associated with Germany come out poorly in Leonard Setright’s book …Those with any Third Reich association are beyond his pale. The conclusion is unavoidable that the author’s open and sincere devotion to his Jewish faith influenced his views about the men and institutions that were part and parcel of the appalling atrocities committed under Adolf Hitler.” This reviewer noted the same tendencies appeared much earlier in Setright’s book, The Designers (1976), when writing about Ferdinand Porsche, while at the same time Setright lavished praise on the Italian designers.

***On the other hand automotive journalist Gijsbert-Paul Berk thought that overall the book was excellent. “I am a great admirer of L.J.K. Setright. He was a brilliant journalist and writer and I know that he was a fan of Bristol motor cars. He wrote an interesting small book about this British make. But one of his masterpieces was without doubt Drive on! –A Social History of the Motor Car.” While I understand his feelings about prominent Germans who had served the Third Reich, I do not belief that his Jewish ancestry had anything to do with his lack of admiration for the products of the German automobile industry. Don’t forget that many of their cars in the 50s, Borgward, Mercedes, Porsche and Volkswagen had independent rear suspension with ‘swing’ axles. And while this type of independent rear suspension improved passenger comfort on the badly maintained postwar roads of continental Europe, it made handling trickier. Setright preferred the conventional rigid rear axle of the prewar Fiedler-designed prewar BMW’s, which became the basis of the postwar Bristol cars. He was indeed no great admirer of Ferdinand Porsche as an engineer. In his book The Designers he wrote on page 94: ”Independent suspension, the backbone frame, and much else began in the work of the genius Ledwinka during the years he spent with Tatra. The triumph of accessibility was a light touring car that did well in competitions, such as the Targa Florio. Paradoxically, its swing axle independent rear suspension depended for its success on badly surfaced roads. Porsche’s mistake in appropriating this idea was in not appreciating its limitations.” Not very nice. But was he wrong?”

More memories of that ‘Merit’ period – LJK was a monthly required tonic in ‘Car’ Magazine for one who was a car nut as well an employee in the British (albeit importers) Motor Industry at the time.

Yes, he was an acquired taste and, yes I didn’t agree with all his thoughts on engineering – after all I worked for VW GB from 1967 to 1975! But the wordcraft was sublime.

Ha! Apropos to nothing, you’ve managed to explain a detail in “The Grand Prix of Gibraltar” that had escaped me (we didn’t listen to BBC race coverage). Ustinov’s BBC personality, Roland Faxter, must have been a play on Raymond Baxter, noted in the first foot note. Thanks!

yes, he really chose esoteric topics ,like a whole book on “Automotive tyres” which gave a terrific insight to that era when the world transitioned from cross plys to radials.

Setright was a hero of mine and I could hardly wait for the next edition of CAR back then. There are a plethora of stories concerning his sartorial weirdness at times…a prize quote coming from DSJ! LJKS arrived at a new F1 car launch clad in what appeared to be pale cream suede jodhpurs, riding boots and a matching pale cream suede jacket, handlebar moustache tips waxed, monocle screwed into eye. DSJ made his way to LJKS and remarked “Do you know Leonard, if you had another lens up your ar** you’d make a damn fine telescope”! I’m indebted to Doug Nye for this gem. One gripe…please don’t perpetuate the myth of Barnato driving the Gurney Nutting coupé racing ‘Le train bleu’…he didn’t. He used a Mulliner Speed Six saloon.

Thanks for the comment and anecdote! Alas, it was Setright who said it was a Gurney Nutting coupe and I dare trusted him!

I met him when I was at Connolly Leather and he moved in just round the corner from me. He was infuriating, stimulating, provocative and rewarding. To get on with him one had to tease him, take the mickey otherwise he would overwhelm you. Go too far and you could turn him off. I thought he wrote like an angel and drove like a devil. He was a wordsmith, albeit a posing one. Posing was one of his delights. If he had been as clever as he thought he was the world would have changed but he was a sight too clever for his peer group which is why they mocked. He drove me once in a Ferrari and I vowed never again. I found out afterwards that at car launches no one would share with him. Car under perfect fingertip control but insanely fast. BUT he never had a road accident!

I used to love LJKS’s columns in Car – a definite one-off and I recommend his autobiography, Long Lane with Turnings, as well as the excellent overview of motoring, Drive On. Regarding the Blue Train Bentley; for many years it was assumed that Barnato used the Gurney Nutting coupe for that adventure. Take a look at the Bentley Motors website for their version of the story which details the research done by owner Bruce McCaw, presumably after Setright wrote the article.

he came up to look at our mckee-cro-sal twin turbo auto trans 4wd can-am car, which cost me under $10k in excellent running condition around ’73. he was teaching at the university of texas and I’d love to hear from any of his students! the fact that I owned a bristol 410 at the time helped us get on well I’m, sure!

I agree with all the tributes to LJK. Now we have the Dutch magazine’s material, how about someone publishing the CAR articles in book form? I’ll place my order now.

I thought that his writing was very interesting but pretentous. Then I met him at the London car show and discovered that he was the perfect condescending English twit. He would have been perfect in the British Foreign Office! After a while I started to challenge his statements and the condesention increased. He used some of his Latin on me and I quoted Horace (only Latin I remembered) to him, and the Latin stopped. Since he wrote with only LJK and I did not know his first name, I calling him by different names such as Larry, Leo, etc. the conversation went down hill. But in leaving I said that he had got his facts right about the Pegaso’s de Dion axle. He smiled as if he has won a point. Never has the frase “very much an acquired taste” been so perfect. Still he had to be read. Michael.