By Brandes Elitch

“I was fortunate enough to live in a time when, if you were willing to tinker with your car, there was a lot of neat stuff to be had. But you were on your own though.”

Recently, Steve Snyder, a fixture in the American Lancia Club for decades, reprinted the club publication originally published in 1977 as “the Aurelia Issue.” (https://velocetoday.com/lanciana-and-friends/) This year, he added more recent material, which brought it to 94 pages. This would be a must-have for any Lancisti. Steve has a few copies for sale; you can contact him at jsteve34@att.net. Steve asked me to deliver a copy locally, which took me to the residence of Mr. G., who kindly invited me inside his home. When I asked about some pictures on the wall, he related the history of his life with cars, and has agreed to share it with our readers, as follows:

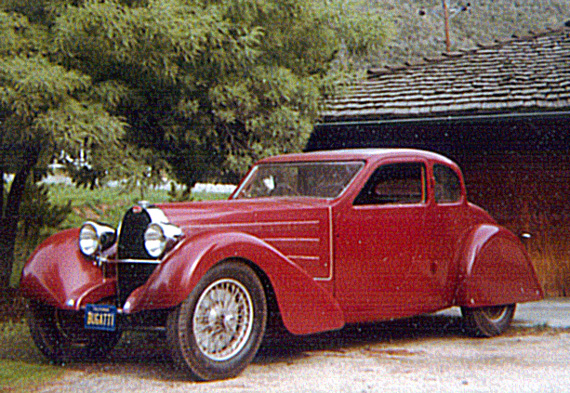

Mr. G was drafted in the Army and in 1955 he was stationed in Verdun, France. A friend told him about a car parked at the Army fire station, just outside the base compound. It had belonged to another soldier who was shipped out after getting into a fight with a local taxi driver. It had what we call today “patina,” having likely been stored under a haystack during the war. The price was $400, but the seller agreed to take $100 a month for four months, which is how, 4 months later, Mr. G came to own his first car: a 1936 Bugatti type 57 Ventoux coupe.

To get it inside the base, it had to pass an American safety inspection, but the tires were bald. He was able to have a local shop re-groove the tires, and even though the white cord was now visible in the grooves, it satisfied the regulation and was registered. He ordered a new set of 5.50 x 18 tires from the Sears Roebuck catalog and had them shipped to the APO address. He also had to register it with the French DMV and get a French driver’s license, which he still has, since it was good for life! When time came to return to the States, he drove to the Bugatti factory near Strasbourg to get spare parts, and then drove clear across France to La Rochelle, where the Army shipped it to New York. After clearing customs, he drove it straight to his family home in Florida! In 1958, he decided to take a trip to New England, so he broke out the British Bugatti Club Owner’s Roster and drove to Boston, stopping to visit the homes of Bugatti owners along the route, telephoning them to say he was in the area and would like to stop by and see their cars. He visited many interesting places, including the homes of Briggs Cunningham and Ken Purdy.

By 1960 he was a graduate student at Stanford University in Palo Alto, California. He had Bunny Phillips build a tow-bar, and so he towed the Bugatti across the country with his 1953 Studebaker Starlight coupe. He rented a small garage for $10 a month, and began a restoration. Here is how he describes it.

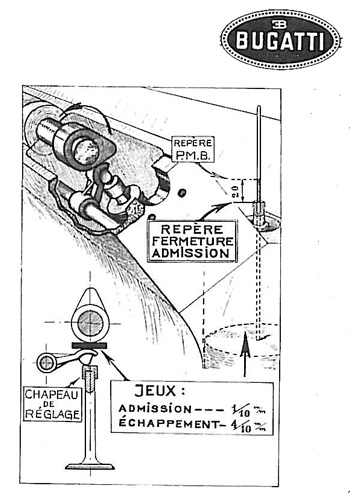

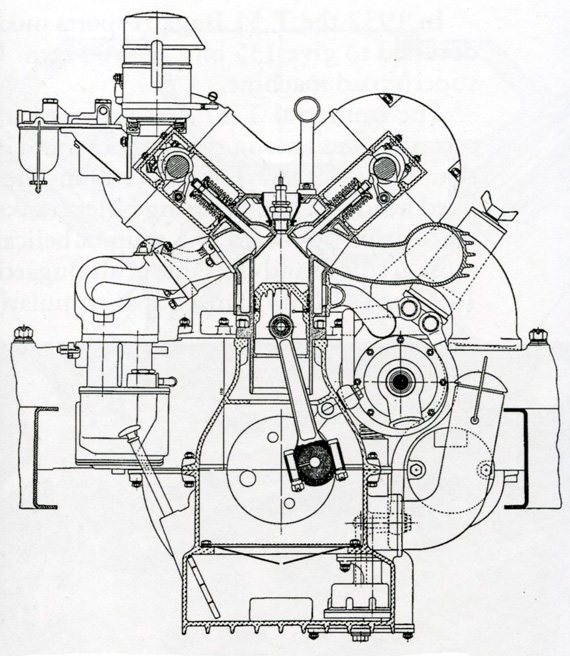

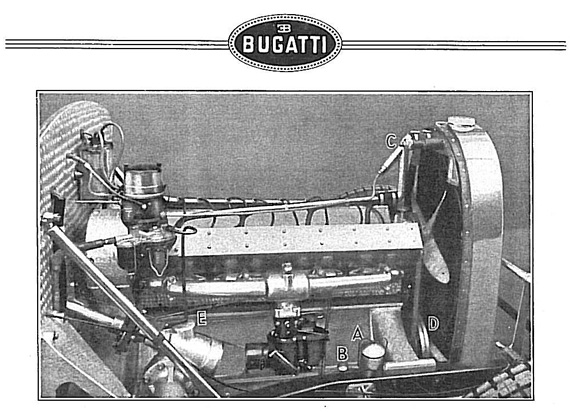

Valve operation and adjustment, from the T57 Bugatti Owners' Manual. Note the small pads over the valve stems, similar to the later Alfa fours. Bugatti, however, used finger followers on the T57 instead of cups.

“To do a valve job on this Bugatti, you must jack up the frame at the back and drop the rear axle, which allows the universal joint at the front of the driveshaft to be disconnected. The rear motor mounts are on a steel plate between the crankcase and the bell housing. Once disconnected, the engine can be removed. The block and head are cast in one piece, so they must be lifted straight up off the pistons. I had to make a special tool to dismount the valves, because a valve spring compressor would not work. It looked like a wine press screwed into studs, tightening the thumbscrews to pull the keepers out of their retainer. Then I made a puller to pull the valve guides. Then you can exit the valves down the cylinder and out the bottom of the block. To adjust the valves, little caps are fitted individually over the valve stems.”

Mr. G pulled the block off the pistons with a cable-winch hung from a rafter in the garage. “I purposely bought the kind with a worm and wheel drive, with a crank arm turning the worm, rather than a ratchet type come-along,” he recalled. “That way, when it came time to put it back on I could lower it a fraction of a millimeter at a time over the pistons.” The block must be lowered over all 8 pistons, two at a time, sticking up above the lower part of the crankcase. Each piston ring must be squeezed by hand as it slips into the bottom of the cylinder.

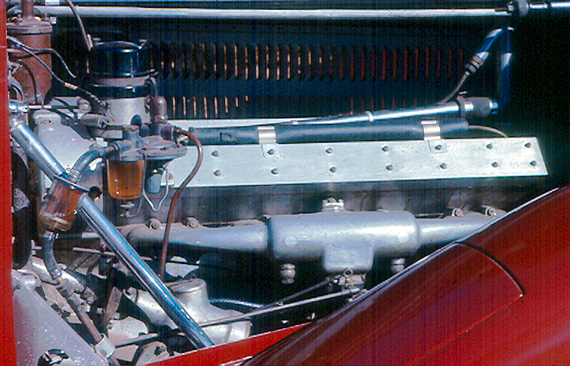

Stripped down, the block was still fairly heavy but he could “walk” it around the floor and lift it into the trunk of his Studebaker alone. He took it to a place in San Jose to have it boiled out and magnafluxed. There was only a couple of thousandths taper, barely any ridge at the top, and it was already about 0.010 oversize. The old pistons had some stuck rings.

This is where Mr. G got brave. “I got new oversize pistons from Bunny Phillips and left the bore alone, just honed it enough to seat the new rings. There was only a small crack, near the bottom of one cylinder. I fabricated a special right-angle drill using an O-ring for a belt drive that would go in the cylinder bore. I drilled out the end of the crack, tapped and countersunk the hole, screwed in a brass flat-head screw, peened over the ends, and filed down flush with the cylinder bore.” He never had any problem with compression or smoke after the rebuild.

“I continued with the restoration, and the only job I had to farm out was the front axle, which I put in the trunk of the Studebaker and took to Los Angeles to have Bunny Philips install new kingpins and reline the front brakes. It doesn’t matter how much you know about cars, the Bugatti is its own thing and you have to learn everything from scratch”

He had the car painted by Bill Hinds in Monterey, and finished the restoration in 1978, 23 years after the initial purchase. He sold it in 1980, and the last time he saw it was at the 1984 Pebble Beach show. Twenty years later, in 2009, he met the buyer again, who told him he had recently sold it to someone in Spain who had it sent to Phil Reilly for a checkover at the demand of the buyer. It was found to be still running well after all those years, despite much of the time sitting in a garage.

From Bugatti to Lancia

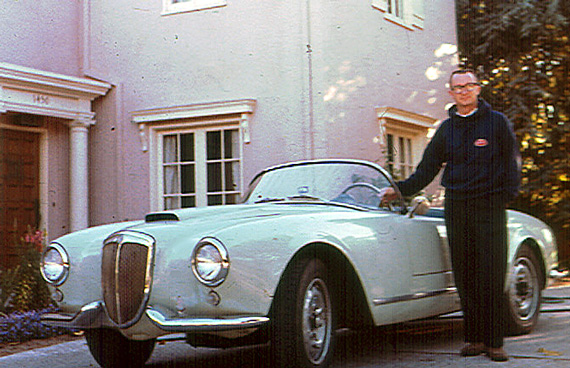

In the course of the restoration, he used the British directory to look up Tom, a local Bugatti owner with a Type 57 and a Type 35 who was a mechanical engineer who worked for Ampex. His new friend had another car, a Lancia Aurelia Spider, which he let Mr. G. drive. He was blown away by the experience, which he describes as “a car that rode like a limousine but cornered perfectly flat.” He was astonished at how light the steering was, almost like power steering. He really wanted a handmade Italian sports car, and shortly thereafter he saw an ad in the San Francisco Chronicle for a Spider on a used car lot in Oakland for $1200.

He had recently come into a $1500 inheritance so, even though it would consume all of his savings, buying the Spider seemed like a reasonable thing to do. When he took a test drive, the driveshaft was out of balance and the wheels were out of balance so as he remembers, “It vibrated like a massage chair, the steering wheel shook out of my hand, and the noise from the prop shaft turning at engine speed sounded like a siren.” Wisely, he had taken Tom along, who advised him that these things were “perfectly normal and easily fixed.” The car did not smoke and only had 60k miles on it, so Tom advised the purchase, whereupon they drove it to Tom’s house and jacked it up to drop the transaxle and sent off to Italy for a first gear pinion. Tom had a well-equipped garage and helped, because Mr. G was a starving graduate student living in a rented room.

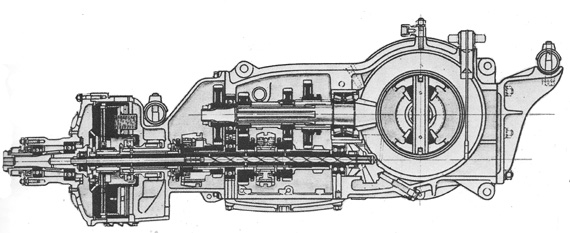

The Lancia transaxle. Note angled bolt holding the pump in place. 'Looks like a drain plug to me,' said Joe, at the local service station.

“Together we put it high up on stands and gingerly lowered the transaxle to the ground with an ordinary hydraulic floor jack. The transmission easily came apart, but was a puzzle, everything coming out the front end. I discovered that what looked like a “drain plug” was actually a special bolt that held the transmission oil pump in place from the outside. Later, I heard horror stories of unsuspecting gas station attendants unscrewing the bolt and having the oil pump fall into the differential and locking up the gears so that the car could not even be rolled on its wheels. I designed and fabricated a special instrument to balance the driveshaft in place on the car. I made a vibration sensor out of a small loudspeaker, with a weight glued to the cone diaphragm. The mass of the weight tries to remain stationary while the body of the speaker, fastened to one of the bearing supports, vibrates. The motion of the weight causes the voice coil of the speaker to generate a voltage that I amplified with a hi-fi amplifier and measured with a voltmeter. I developed a procedure for taking data and plotting it so the optimum position and amount of weight could be fastened to the universal joint on the shaft.”

“Another fortunate occurrence was that British Motors decided to drop the Lancia brand, and their entire stock of parts came up for sale. I bought a new wood-rim steering wheel, chrome grille, taillight lenses, rubber boots for the rear axle universal joints, rubber covers for the pedals, plastic Lancia badges for the grille, and many other parts I never needed.”

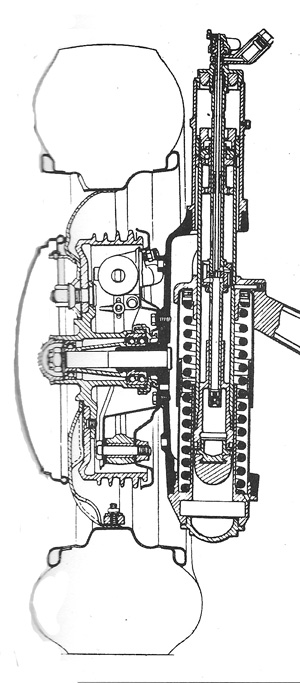

The cross-section of the front suspension shows the rolled rim of the wheel that prevents using ordinary balance weights. It also shows how far the wheel is outboard of the kingpin, that makes front wheel balance very critical.

He bought a static wheel balancer from JC Whitney and screwed flat pieces of lead on the inside of the rim to balance the wheels, which are about 6 inches out from the kingpins. At that point, the car was deemed roadworthy, and for the next couple of years he enjoyed driving it, including a trip to Monterey where he proposed to his girlfriend. Upon graduation, he got a job on the Monterey Peninsula, and discovered to his chagrin that the changeable weather was not conducive to an open top car. Carmel Valley, where he lived, would be bright and sunny, but downtown Monterey, where he worked, would be cold and foggy in the summer and cold and rainy in the winter. When he went over Los Laureles Grade Road (familiar to all attendees of the Historics, because it is the road to the track) he had to put on the side curtains, and then the windshield would fog up and the heater core, “no bigger than a bagel,” could not defrost it. The wipers just flapped back and forth without actually wiping the screen.

About this time, he met another Lancia owner, who wanted to buy the Spider. Mr. G. told him that if he ever saw a fourth series coupe, he would like to know about it. One day he got a call from the other person, who said, “I just bought a fourth series B20 coupe for you!” He offered to trade cars. It turned out that the only things wrong with the coupe were a bad first gear and a noisy exhaust.

“By then, I had learned the trick to dropping the transaxle. There is a trap door in the floor of the trunk of all Aurelias for access to adjust the inboard brakes. By removing the trap door, a chain hoist can be used to support the transaxle from above, and lower it to the ground. Then, the rear end of the car can be jacked up and the transaxle rolled out from underneath, on its own brake drums. I found a non-running Spider for sale and swapped the transaxle from the parts car into the coupe. I drove the B20 regularly for several years, and it is still my favorite of all the many cars I have owned.”

This concludes the first half of our story. Next month, we will resume the story with the history of another truly fabulous car and how he came to acquire it.

These days it is hard to find an exceptional and sophisticated enthusiast such as Mr. G.

For me, this is one of the most interesting articles I have read on “VeloceToday”.

What a delightful story. I once found a Bugatti in an old parking garage near the Bastille in Paris. If I had decided not to pay my French income taxes I would have bought it. By then inflaion had set in and the price was $7000.

The quotes of Mr. G. and the gentile lack of frustration expressed make this a “period” sounding enthusiasm and willingness to interact with those peers along the route.

I was very fortunate to have an uncle that was a similar enthusiast in Montana, of all places. His description of his exploits with various cars, including a Cord Beverly coupe and a Phantom II Rolls Royce had a similar willingness for automotive adventure. His many auto acquisitions were engaged with a very meager income and were an inspiration for me and my automotive avocation.

Thank you for a very personally nostagic article. jpn

What an amazing man. An analytical brain that would challenge Einstein. I can’t wait to read the second half.

Yes, I remember the times. although I stayed in the “States”, the cars were here as well. I bought a running Singer roadster for $500, an Alfa 1900C cabrio for $1500, and swapped the Singer for an Aero HRG. It was a different time of life when I had the energy and the spirit to enjoy it. Today’s almost foolproof (except for GM) cars, I can also enjoy the prospect of reliably traveling from here to there without any “interesting”mechanical failures. I am glad that I grabbed the opportunities when I had them. No regrets. – Don

These cars represent the mechanical age which sadly has long passed . The rush of adrenalin to bring such cars back to life felt by people like Mr G cannot be repeated in today’s digital and electronically managed cars . It’s like falling in love with kitchen appliances !

in 1955 I was stationed 35 miles south of Verdun at a small army chemical base, I paid $300.00 for a used Morris minor with a 850 flat head motor,how come I didn’t know about this car!!!

Denny

What a story! This is one Bugatti who travelled a lot! Is it possible to locate where in Spain this car might be by now? I will travel through Spain extensively in March and would not mind looking for it, and report back… (maybe a part 3 for your article?)