The Tipo C monoposto was a breakthrough design for Alfa Romeo. Giovanni Guidotti, a long-time employee of Alfa Romeo, remembered the initial test of the prototype and the bizarre events which followed. He originally told the story to a prominent member of the “Alfisti” more than thirty years ago. The story was recently passed on to me. Although possibly an apocryphal tale, this is Guidotti’s story.

Story and montage by Peter Darnall

Alfa Romeo was a major force in European racing during the early 1930s. Vittorio Jano’s innovative designs had made Alfas the cars to beat in both sports car and Grand Prix venues. However, the economic hardships of the Great Depression and the years which followed brought government control to Alfa Romeo with ever-increasing pressure to produce materiel for Mussolini’s military ambitions. Racing activities had been turned over to Scuderia Ferrari with an arrangement which allowed the Portello factory to design and build the cars while the Scuderia campaigned them.

The AIACR (Association Internationale des Automobile Clubs Reconnus), which was the governing body for international motor racing, had decreed that beginning with the 1934 Grand Prix season, race cars would not weigh more than 750 kilograms (about 1650 pounds), minus the weight of tires, fluids and driver. Although Vittorio Jano’s masterpiece, the P3 monoposto, met the weight requirements of the new formula, the vintage Alfa racer could not expect to compete with the technologically superior German Mercedes Benz and Auto Union machines.

European nationalism was at a fever pitch. The German Silver Arrows, which enjoyed substantial financial support from Hitler’s Nazi regime, were reaping enormous propaganda benefits from their successes. Italian race driver, Achille Varzi, had switched from Alfa Romeo to drive for Auto Union in 1935. The fear of losing other Italian drivers to the German side reached the highest levels of the Italian government. Benito Mussolini, Il Duce himself, reportedly used his influence to persuade Tazio Nuvolari to sign with Scuderia Ferrari and race Alfa Romeos.

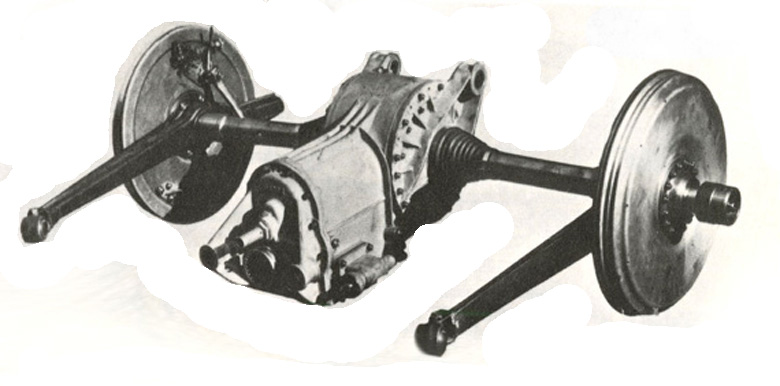

8C rear suspension. The rear suspension for the Tipo C was independent using swing arms — a first for Alfa Romeo. The transmission was rear mounted and combined with the differential.

Alfa Romeo desperately needed a competitive Grand Prix contender. Vittorio Jano and the engineering group at Alfa Romeo responded with the Tipo C. The Tipo C incorporated a number of innovations, including independent suspension for all four wheels, a rear mounted transaxle, hydraulic brakes, and streamlined bodywork. Although experimentation with a Dubonnet type front suspension system had been carried out previously on the P3, the configuration of the front suspension for the Tipo C was completely different. The rear suspension used a swing axle design.

Hopes were high as the new Tipo C was brought out for its first test drive. Tazio Nuvolari, Scuderia Ferrari’s ace driver, would put the new car through its paces. If all went well, Alfa could soon have a competitor for the German blitzkrieg.

Unfortunately the test was very disappointing.

Giovanni Guidotti recalled that Nuvolari was visibly upset as he climbed out of the car. The fiery Italian did not mince words when he described the Tipo C’s erratic handling. He characterized the Tipo C as dangerous and stunned the assembled group when he announced that he would not race the new Alfa.

An urgent meeting was set up at Portello following the Tipo C test. The engineers at Alfa Romeo assumed the handling problems were related to suspension issues, but this was unfamiliar territory to them. Concerns relating to roll centers, spring and shock absorber rates, etc. were simply not understood at the time.

There was one man, the engineers suggested, who understood the complex dynamics of independent suspension systems and who had considerable experience with the swing axle configuration. That man was Doctor Ferdinand Porsche.

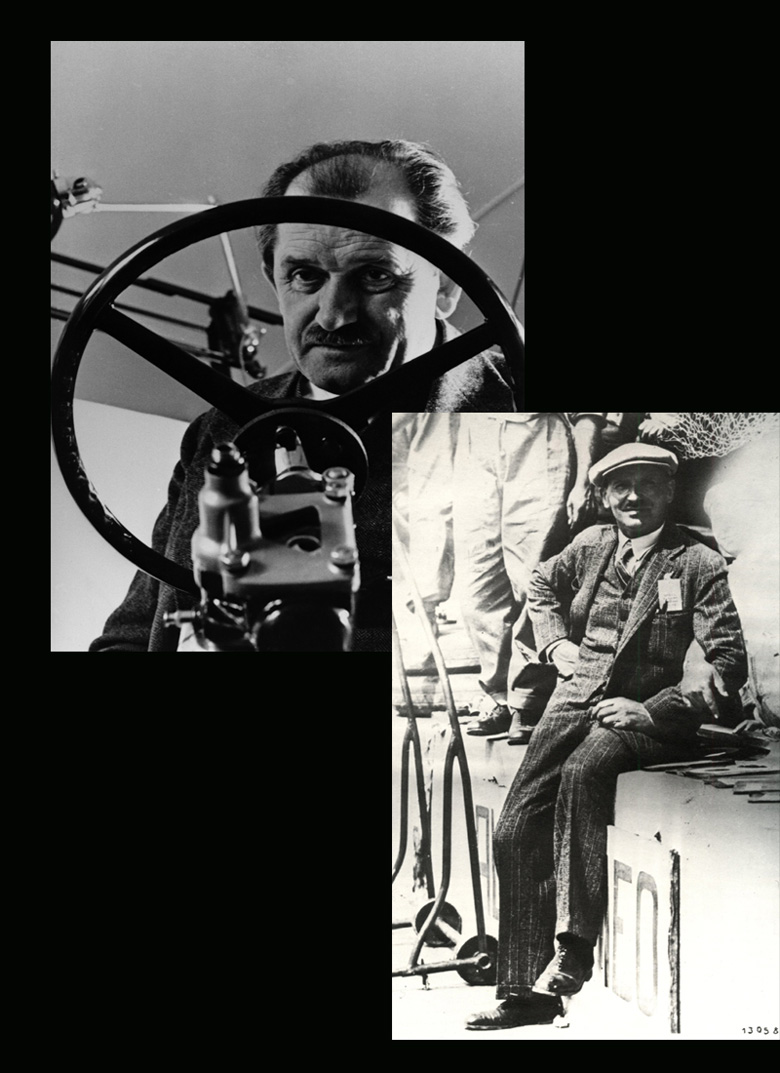

Ferdinand Porsche, who was one of the leading automotive designers of the 1930s, had the knowledge and experience, but he was the engineering talent behind the German Auto Union race car. Unfortunately, efforts to reach Doctor Porsche at the Zwickau headquarters in Saxony had not been successful. Time was short and there was now only one alternative: drive to Zwickau and meet with Doctor Porsche in person.

The fastest Alfa road cars were made available to the team. The group left the following morning for Zwickau, which lay about five hundred miles to the north. Upon arrival at Auto Union headquarters, they were met with disappointing news: Doctor Porsche was not available. He was on vacation and had left strict orders that he was not to be disturbed. As the disheartened Italians were leaving the building, one of the German mechanics took them aside and whispered surreptitiously that Doctor Porsche could be found at a small summer resort on the Adriatic Coast.

The Italians returned to the road. The sprint to Zwickau had turned into an odyssey; their destination now lay far to the south and the clock was running.

Following the mechanic’s directions, they found the hotel and anxiously made their way inside. The proprietor listened to their story and then walked to a large picture window which overlooked the beach. Pulling back the curtain, he pointed to a distant figure of a man standing in the water. “There,” he said, “is your Doctor Porsche!” Guidotti and his group ran outside and crossed the beach to the water’s edge. The man, who was standing in the water with his pants legs rolled up over his knees, was too far away to recognize. They yelled and waved to get his attention but he seemed to ignore their overtures. They had no choice, Guidotti recalled, but to take off their shoes and socks, roll up their trousers and wade out to meet him.

As they approached, he became agitated and shouted at them in German to go away. He was indeed Doctor Porsche—they recognized him from photographs—but this was not the dour engineer they expected to meet. Guidotti laughed as he recalled the rolled up pants, the angry red face, and the large white hankie covering the bald spot on his head. Of course the Italians were hardly dressed for the occasion either . . . The crucial meeting with Doctor Porsche was off to a bad start.

Eventually the Italians were able to convince Porsche to wade ashore to hear their case and to review their Tipo C drawings. Porsche did suggest changes to the Tipo C suspension configuration, but his recommendations were necessarily limited due to the short time before the next race. The problematic issues concerning front and rear roll centers would also have to remain unaddressed for the time being. There would be little opportunity to test different viscosities of oil in the front dampers or to experiment with different spring rates. While it is not certain that drop straps were fitted to limit the rear suspension arm travel for the swing axles for the original test, these restraints were in place when the Tipo C was readied for its next test drive.

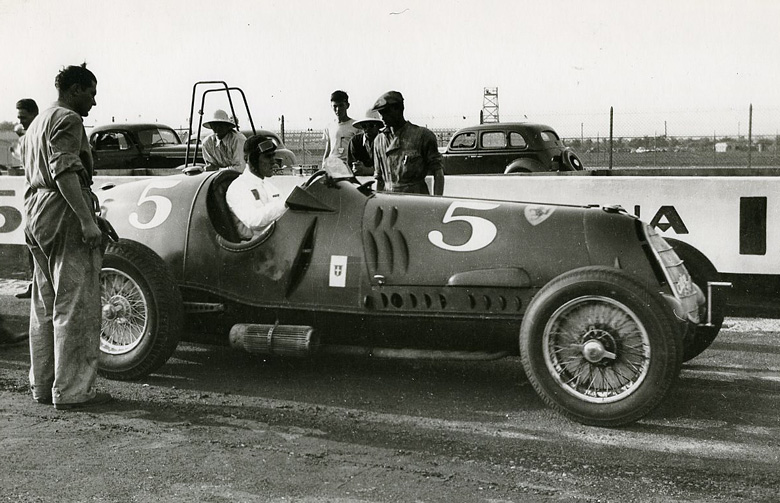

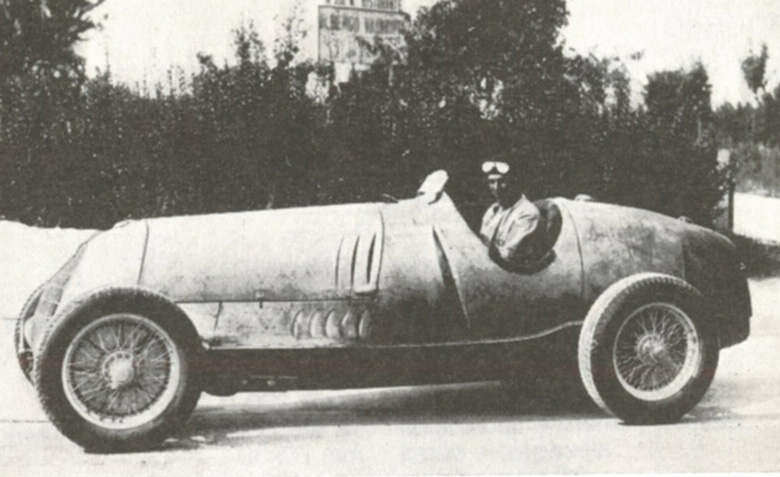

A rare photo by Hemp Oliver from the Dale La Follette collection of Nuvolari in the 12C 36 at the Vanderbuilt Cup in 1937. Although Nuvolari won the 1936 Vanderbilt Cup, he DNF’d in 1937 and the Germans won.

A second test session was set for Tazio Nuvolari to drive the revamped Tipo C. His assessment, which was in Italian, was related to me as follows: “The car is still bloody awful, but it’s better; it doesn’t seem so keen on killing me now. I’ll agree to race it.”

EPILOGUE

Tazio Nuvolari won one of the greatest victories of his career when he beat the Auto Union team with a Tipo C Alfa Romeo on the narrow streets of the Montenero Circuit at Livorno to win the Coppa Ciano on August 2, 1936. To do so, he had to overcome a multi-lap deficit and roar through the entire field to take the win . . . but that’s another story.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Giovanni Battista Guidotti (1902–1994) joined Alfa Romeo in 1923 and remained active with the company until shortly before his death at the age of ninety-two. Although he described his responsibilities as “engineer and race driver,” he held positions of engineer, racing driver, team manager, test driver, and consultant with Alfa Romeo over the years. He was a fine race driver, competing with Nuvolari, Campari, Varzi and others behind the wheel of an Alfa.

A wonderful story.

A cute story, but hardly believable. For example, could it have been true in 1935 that “The engineers at Alfa Romeo assumed the handling problems were related to suspension issues, but this was unfamiliar territory to them. Concerns relating to roll centers, spring and shock absorber rates, etc. were simply not understood at the time.”? Or would Porsche, a master opportunist and solicitous of Hitler and well aware of the nationalistic aspects of racing at that time, have risked his position to advise arch-competitors?

I do believe the part about Mussolini and Nuvolari, though.

It’s wonderful story indeed but far away from history. The rear axle is genuin Porsche designs numbers 63 and 69. In case Veloce Today is interested I can supply the documents.

Kind Regards

Martin Schroeder

The yelling at the beach could have gone something like this,

Upon spotting Porsche in the water,

Guidotti : “Herr Doktor Porsche! Herr Doktor Porsche!”

FP: “Nein! Nein!

Lass mich allein! Geh weg!”

(Dr Porsche, Dr Porsche, no no leave me alone, go away!

Well an other interesting story, however a long time ago and during a different time. Knowing the ALFA ROMEO pre-war history and their cars well, to me this story is hard to believe. Vittorio Jano and his team did not just started building race by that time. Yes, they just finished a whole new suspension so adjustment where required but no time left.

What seems to me the case is Nuvolari’s behaviour in the story. By that time he was not only a very good and experienced driver, he sat very high standards on himself AND his equipment. One of the reasons he stayed alive wile most of his colleagues got themselves killed. Again he did not want to disappoint Mussolini who supported Alfa Romeo and the Italian Racing scene.

In short: Not only the Germans, as well the Alfa team had a fairly good knowledge of race-car dynamics by 1934.

Cheers Alexander