We asked Gijsbert-Paul Berk to tell us about his visits to Saoutchik and Franay in the early 1950s, as mentioned in Peter Larsen’s three volume book on Saoutchik. One question led to another and soon we had a very interesting article about a very special man.

From the Archives, November 2014

Story by Gijsbert-Paul Berk

Thank goodness for Sir Peter Ustinov. The versatile British actor was known to many car buffs of previous generations, even those with little theatrical interests, thanks to his hilarious Riverside recording of the Gibraltar Grand Prix and other records. However only intimates were aware that Ustinov himself was a lifelong car enthusiast with a penchant for classic automobiles and sports cars.

Yes, he’s quite mad, we are sure of it…

In his endearing biography Dear Me, Ustinov reveals that as a young boy he honestly believed that he was a car. “I was an Amilcar,” he wrote. There are probably a number of subscribers to VeloceToday who recognize such a mental aberration from their own childhood; I, for one, found Ustinov’s admission very reassuring, because I remember going to school, always running and making brumm, brumm sounds, like changing into a lower gear for each street corner. Most adults along the route looked at me with bewilderment, certain that this small boy was quite mad.

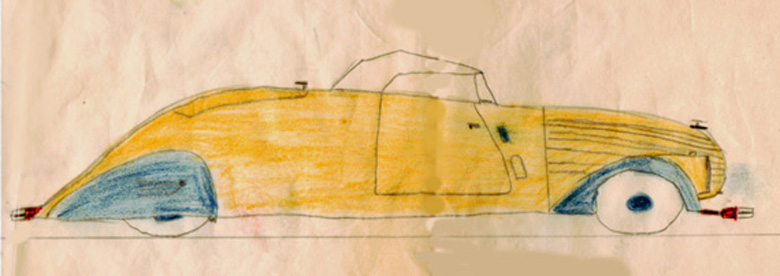

Drawing by GPB 4 or 5 years old, 1934-35. My mother told me that from the age of four most of my drawings were of cars. This one she conserved and I found it among her personal papers after she had passed away.

My other favorite subject was Lyare, our very gentle and beautiful Persian cat. As I grew up, I still made drawings of my own dream cars but also started making car models, using the wheels of Dinky- and Tootsie Toys and clay or a substance called plasticine, which remained malleable, for the bodywork. I also made clay effigies of our cat and of busts of family and friends. My mother, who was a dress designer and very artistic, dreamt that her son was destined to become the new Michelangelo. She arranged that every Saturday I got lessons from Marian Gobius, (1910-1994) at the time a quite famous Dutch sculptress. Gobius was also a marvelous teacher who taught me a lot about drawing and modeling in clay.

This drawing of a large two-seater convertible came from the same file from 1935-36. Funny thing is that when I saw it, I remembered making it. It was inspired by an American cart that was parked near our home.

Occupied but with homemade radios under the blankets

The German occupation and the regular air raids by the allied air forces made living in the larger Dutch cities, such as The Hague, rather unpleasant and dangerous. For this and other reasons my mother decided that I should go to a boarding school near the midsized provincial town of Zeist, in the center of our country. I very much enjoyed living there among boys of my own age, some of whom have become friends for life. But my interests changed drastically.

Even the clever amphibious version of the KDF wagen (later Volkswagen) did not inspire me much. I never believed that the German army could cross the Channel with these Schwimwagen, although their poor soldiers sang ‘Und wir fahren gegen England’(And we’re going to England). Thus we never lost faith in the final victory of the Allies.

Losing my interest in cars, I became fascinated by electricity and the functioning of radios. The German occupiers had officially requisitioned all the radios of the Dutch civilian population and listening to the emissions of the BBC, or the Dutch language program Radio Oranje, equally broadcast by the BBC, could land one in prison.

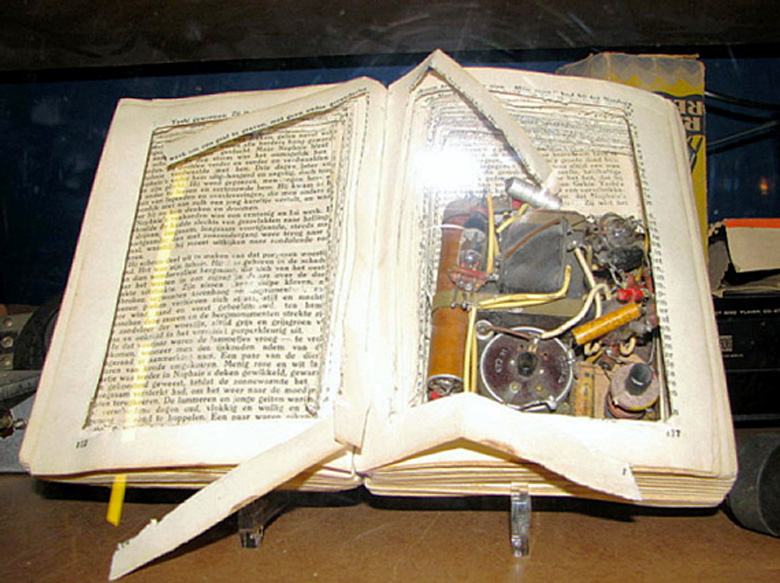

During the German occupation many boys of my age built Crystal radio receivers. Some were fitted in books or even bibles, because in these years was strictly forbidden for Dutch civilians to possess a radio set.

What better incentive for young adolescent boys than to build their own radio receiver! By reading old books and magazines I discovered how radio valves or tubes and heterodyne sets worked. But I began my new adventure by building a simple crystal radio or so called ‘cat’s whisker receiver’ and used the top part of an old telephone horn as a headphone. Its advantage was that you needed no electricity and could listen to it in your bed, hidden under the blankets.

Learning to work with metal

From mid-September 1944 (the Battle of Arnhem) till after the liberation of the northern parts of The Netherlands in May 1945, our boarding school at Zeist was closed, at first because of the hostilities around Arnhem but also because our occupiers tried to apprehend all able bodied boys and men above 17 to work as slave laborers in their German factories.

I was only 14 at the time but my personal problem was that when my school shut down, my mother was not living in her home anymore, but in hiding with friends. A ‘good’ policeman had warned her that the Gestapo wanted to arrest her. She was involved in ‘highly illegal activities’; sheltering Jewish compatriots and helping them to evade from being deported to a concentration camp and someone had betrayed her. Cunning and luck kept my mother out of the hands of the Germans.

After May 1945 many prewar cars reappeared after being hidden away to prevent them from being requisitioned by the Germans. Friends of my mother owned a Hispano-Suiza with an aluminum coupe body made by the French coachbuilder Million et Guiet. It was an impressive automobile and it inspired me to construct this 1/24 scale model

When my school closed, I should normally have gone to stay with my mother, but this was not possible now. My parents were divorced but during school holidays I regularly stayed with my father. He was the technical director of a midsized factory and he always allowed me to go with him to the workshop, where a number of craftsmen, who were over the age to be hunted by the occupation forces, were still employed for maintenance and repair work. Thus during the winter of 1944 – 1945, I learned from them how to machine, form and weld metal. This would prove to be very useful.

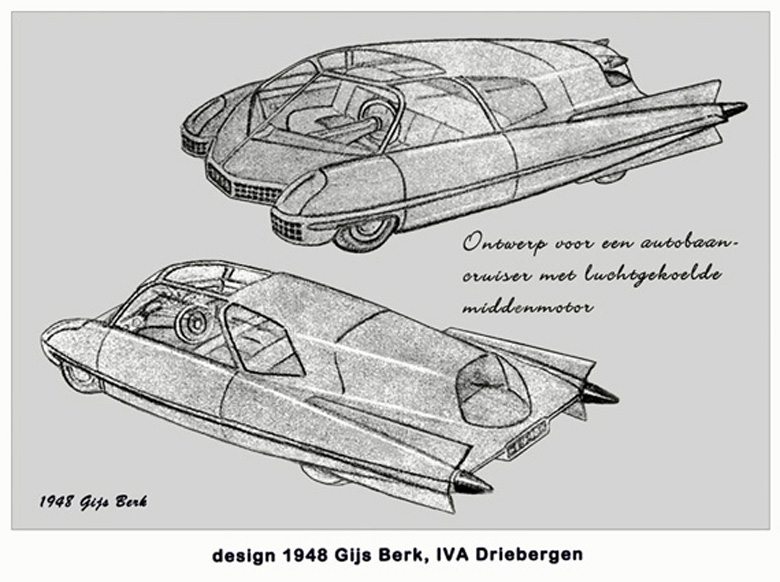

The house magazine of the IVA in Driebergen in 1948, published an article with this illustration of a futuristic and aerodynamic highway cruiser for 2/3 people. In the text I proposed that such a car should have a four-cylinder boxer engine (Volkswagen) in front of the rear axle. My styling was obviously inspired by aircraft and American magazines.

Back to normal

After our country was liberated and the German army had surrendered, life in The Netherlands slowly went back to normal although there was a lot of damage, due to bombing and fighting. Food and coal were still scarce and many products were only available with coupons. But people were glad that the war was over and the reconstruction efforts united them.

After the liberation of Europe there were lots of fine radio receivers (such as Hallicrafters) to be found at US Army surplus dumps. I still think that some of those Hallicrafters short wave radios are classic examples of good industrial design. After schoolwork I was allowed at my boarding school to repair or rebuild radios and sold many of these sets. My teachers also bought some, but they got them of course at a discount. I resumed building and restoring radios in my spare time. But now one could buy valves (cathode ray tubes) and complete ex-army radio equipment (Hallicrafters were my favorites) from surplus dumps, so I could construct more elaborate sets. As radios were still in short supply this was quite a lucrative hobby, at least up until the moment that the Philips factory in Eindhoven introduced their first postwar model… I must admit that they were superior to my radios!

During the 1949 summer holidays at the IVA in Driebergen, I helped my friend Paul Kerssemakers (hence the name KarSport) to construct a small mid-engined runabout. As powerplant we used an air-cooled single-cylinder Sarolea, salvaged from a three-wheeled carrier.

In the meantime, my interest for cars was awakened again. In those postwar years there were suddenly lots of interesting cars on our roads. First of all of course the allied army vehicles we had never seen before such as Jeeps, Dodge command cars, GMC and Ford CCKW trucks, their amphibious twins the DUKWS and Canadian build (CMP) personnel carriers. Also many prewar cars reappeared back in the daylight after being stowed away under straw bales in dusty sheds and isolated farmhouses to prevent them from being requisitioned by the Germans. And in The Hague I saw for the first time shining new automobiles from Detroit.

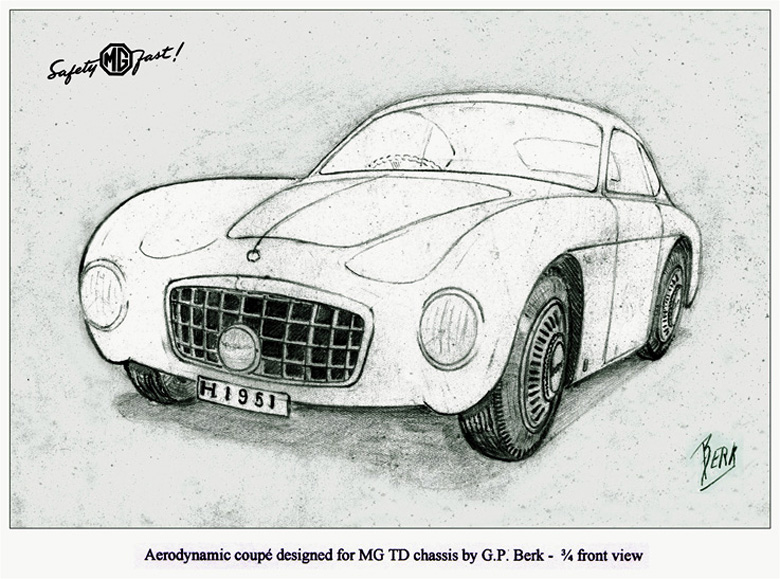

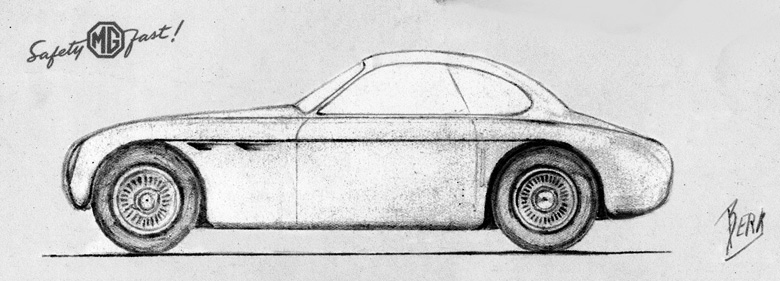

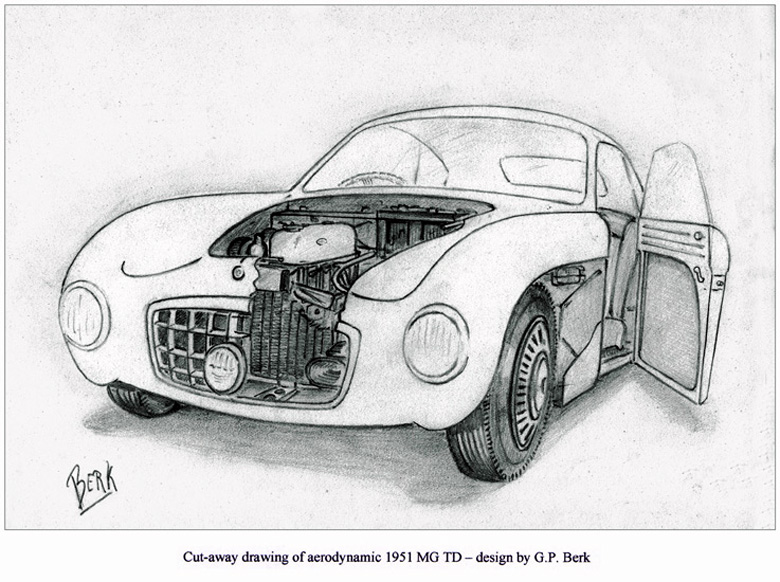

In 1951 my stepfather bought a small MG TD roadster. It was a pleasant car to drive but compared with the previous MG TC, I found the body style a bit heavy and crude. And in my opinion it was not a very modern design. So I made these drawings to show how an aerodynamic MG sports coupé could look.

My stepfather, who like my own father was an engineer, remarked that my conversion of the nose of a MG TD would cause problems with the cooling of the engine. But after studying literature about cooling systems I discovered that with a pressurized system as was used in aircraft (among others in the Spitfires) I did not matter if the header tank of the radiator was below the cylinder head.

Apprenticeship at Gatso

After high school I enrolled at the Institute for Automobile management IVA at Driebergen. The curriculum consisted of a mixture of practical automotive technology plus business and management tactics and languages. (In Britain the IVA would at that time have been known as a Polytechnic, in the US perhaps MIT) A lot of my co-students were the sons of car dealers. It was an interesting study and because the managing director saw one of my drawings, he asked me to design the publicity posters for car rally the IVA held every year and so I became involved in the organization of this event.

Presenting his Gatso Aero Coupé to HRH Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands at the 1948 Amsterdam Motor Show. The Prince (in glasses) never bought a Gatso but became a lifelong admirer and friend of the versatile Gatsonides.

During this rally I met Maurice Gatsonides, the builder of the streamlined Ford-based Gatso sports cars, and managed to arrange for an apprenticeship in his workshop at Heemstede. Unfortunately, as a result of financial difficulties, the Gatso business folded before I had completed my apprenticeship, and as a disappointed boy I went back to Driebergen to resume my studies and finish my exams.

I was keen to find work in the automotive world but had no ambition to run a garage or dealership or become a car salesman. What I really had set my mind to was becoming involved in the construction and design of automobile bodies. But apart from DAF, the Netherlands had no car industry. Ford and Morris had assembling plants and there were a number of coachbuilders. On my father’s advice I followed a seminar about time and motion studies to become better acquainted with industrial processes, and my mother persuaded me to attended evening classes at the art section of the Free Academy in The Hague in order to improve my drawing techniques.

In the spare time I had I produced a portfolio of sketches of cars and made a few scale models.

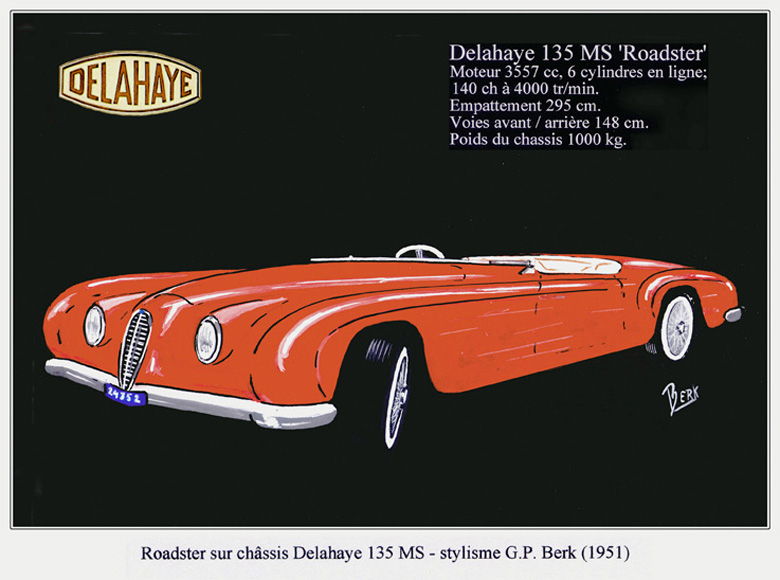

This rendering for an open sports roadster on a Delahaye 135 MS chassis I made for my interview with the coachbuilder Pennock in The Hague, who worked for the Dutch distributor of the French make. I admit that the nose was inspired by that of the Jaguar XK 120. Because I knew that this car was well liked by Americans, a potential export market for such a car. But the crease in the wing line was an adaptation of that on the mudguards of the very classic Pennock convertibles, originally designed by Chapron.

Then I obtained interviews with two Dutch coachbuilders: Pennock and Van Rijswijk. In those days Pennock was well known for his elegant Delahaye convertibles. In order to limit paying the sky-high import duties the Dutch importer of this French make had arranged with the factory in Paris that his coachbuilder in The Hague could produce the bodies for the cars sold in The Netherlands. Pennock then obtained the permission from Chapron, the main supplier of Delahaye and Delage factory bodies in France, which allowed them to use Chapron’s basic prewar body design. Van Rijswijk had been a successful coachbuilder up to 1940 and even obtained the title of ‘Hofleverancier’ (Purveyor to the Royal household). But since the war they mainly concentrated on body repairs. So neither of these companies offered much scope for a young and eager designer. Where else would a young man go to find his fortune?

Paris, of course!

Part II Paris and the world, coming next.