By Pete Vack

Although new information has surfaced about the Cisitalia Abarth 204, in looking over years of notes, letters and books, we note that as far back as 30 years ago historian John de Boer got the facts down and got them right. He passed his knowledge on and we absorbed it into the first edition of this author’s Illustrated Abarth Buyer’s Guide.

De Boer, along with collector and owner Serge Lugo, was one of the first to realize that the Cisitalia Abarth 204 is a car which marked a transitional phase in the history of Cisitalia and Abarth, and as such an important milestone for both companies; he also recognized that the ensuing Abarth 204 A berlinetta was not a 204 buy more correctly a 205, ending the confusion and properly assuming that the first Abarth built with the Abarth badge was the 205.

The 205 Abarth with a Vignale body by Michellotti; the first Abarth and badged as such. Photo by Alessandro Gerelli.

The 204 was a great success on the track, winning the 1100cc Italian National Championship in 1948 and 1949; and despite the Cisitalia badge, the 204 (or 204A for Abarth?) was, according to Italian historian Nino Balestra, the first car Carlo Abarth created, using his contacts with the Porsche family that stemmed from the mid-1930s. And it was the last-Italian made Cisitalia while under the control of its founder, Piero Dusio.

A retrograde step?

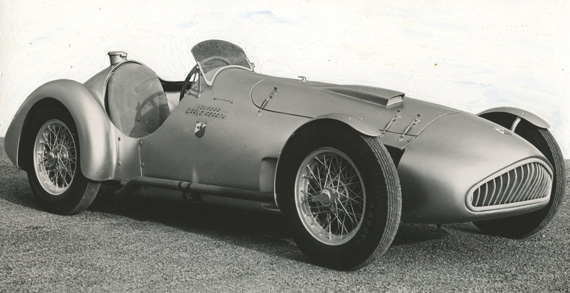

Forgetting for a moment the model name, if one looks at the styling of the 204 in comparison to the Cisitalia 202 coupe and sports racers, one would be forgiven to assume that the minimalist cycle-fendered 204 came before, rather than after the beautiful Cisi coupes and spiders. But in fact the 204, as its name might imply, post-dated the advanced Savonuzzi Mille Miglia roadsters. Abarth was looking to save weight, as the only engine available was the Fiat based 1100 unit as modified by Cisitalia. Inches and pounds had to be shed quickly if the car was to be competitive. It was a winner right out of the box, simply because it was faster than the older 202s. Or maybe it had something to do with that new Porsche front suspension.

Abarth and Porsche

Already a famous Viennese motorcycle champion, in 1934 Carlo Abarth challenged the famous Orient Express train from Vienna to Ostend. Using a Sunbeam motorcycle and sidecar he beat the train’s time and became rather well known. Shortly after his famous run, Abarth married the secretary to Anton Piëch, the husband of Ferdinand Porsche’s daughter. Contact with the Piëch family was established and maintained.

After the war, Abarth, now living in Merano Italy, obtained written authorization on September 30, 1946, to “represent the interests of Ferdinand Porsche Jun (Ferry) in the concessions of licenses construction commissions in Italy.” (Greggio page 48).

Team Germania

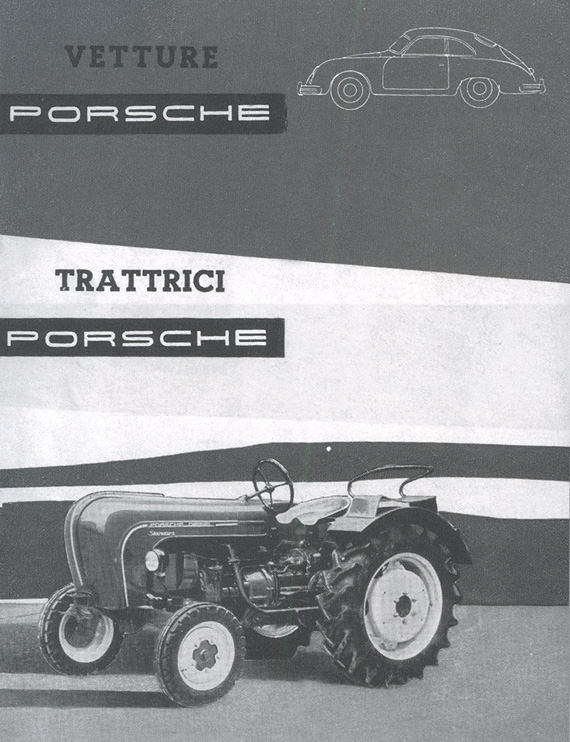

Abarth was now encouraged and with the help of Rudolph Hruska, a Viennese engineer working for Porsche in Italy, contacted Tazio Nuvolari in regards to a Porsche tractor project and the creation of a new Grand Prix car based on drawings by Ferdinand Porsche, then still in jail in France on war crimes charges. As a result, Corrado Millanta and Count Johnny Lurani organized a meeting in October of 1946 with Piero Dusio, then on top of his game with the successes of the D46 monoposto, designed by Italian engineers Dante Giacosa and Giovanni Savonuzzi.

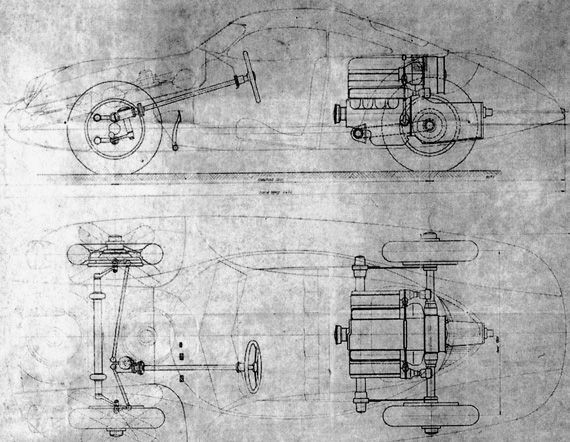

Lurani and Millanta both agreed that Cisitalia was the only Italian car company that might be able to realize a race car from the Porsche drawings. Plus, Dusio was extremely interested in the Grand Prix project. Dusio acted quickly, paying Porsche for the designs and rights to not only the 360 GP car but to a sports racer designated the 370. The money was used to get Porsche out of jail, and in Turin, the era of the “German” team at Cisitalia began on February 3rd, 1947. As part of the package deal with Porsche, Carlo Abarth and Rudy Hruska were hired on by Dusio; Abarth would be the sports director at Cisitalia while Hruska would be put in charge of the development of the Grand Prix car.

The remarkable Cisitalia/Porsche Project 370, a drawing for a V8 in GT form. A Berlina was also designed. The V8 was to be a 2 liter DOHC with an alternative flat 8 on the boards. Dusio put the time and money into the Grand Prix car instead. Click to enlarge.

Abarth moved to Turin but with a new woman in his life, Nadina Zeriav, whom he had met while in Yugoslavia during the war years. Along with Hruska and then Robert Eberan Eberhorst, Abarth completed the “German” (all, however, were Austrian by birth) team in Dusio’s Turin factory. Socially, life was not always easy for the team, as there was still plenty of resentment stemming from the war.

Abarth’s baby

Dusio’s obsession with the Porsche Grand Prix car meant that other activites were neglected. D46 creator Dante Giacosa left to go back to work for Fiat, Giovanni Savonuzzi left in 1948, not happy with having to work with the “Germans”, and as sports, or competition director, Abarth then had the opportunity to develop a few ideas of his own. Like Ferrari, Abarth as not a trained engineer but was able to engage others—including engineers Scholz, Tallero and Manini to realize his visions. Under Abarth, the D46 monoposto was improved, and three or four Savonuzzi Nuvolari 202s were modified to keep them competitive.

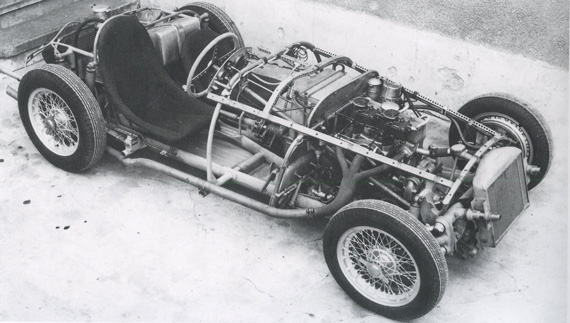

But he also created a chassis. The engine would be the same Cisitalia 1100 and 1200 cc units with the sturdy Fiat four speed. However, Abarth discarded the Giacosa/Savonuzzi space frame, substituting a large tubular chassis instead. Keeping the rigid rear axle and leaf springs, he changed the front transverse spring suspension in favor of a Porsche-like torsion bar front end. In fact, using his contacts at Porsche, Abarth sent technician Cornelio Maffiodo to Porsche to obtain five complete Porsche front suspension assemblies, which were mated to the new tubular chassis.

Some give credit for the body design to Savonuzzi, and it seems likely that Abarth would have turned to the great designer for assistance, just as he asked Hruska for a hand when engineering the chassis. And it also seems likely that Rocco Motta did the panel beating, though we can’t find a particular mention of this. Motta did however do the metal work for the D46 monoposto and other Cisitalias.

Whatever, the 204 (or 204A) was an immediate success, introduced to the tracks on May 9, 1948. It retired but won at Montova on June 12 and continued on to win the Italian championship, with a rich, young driver by the name of Guido Scagliarini who would helpf finance Carlo Abarth’s new venture.

Abarth and Nuvolori

The Cisitalia Abarth’s greatest victory was not due to the fame of the event but of the driver. On April 10 1950, Tazio Nuvolari won his last competition, taking a 204 to a class win in the Palermo-Monte-Pellegrino race.

The 360 project was already getting Dusio down and in February 1948 Cisitalia was already in talks with the Argentine government and a business called Autoar. However, it was not until 1949 that the plan came into being, and part of the deal included the construction of a sturdy Jeep based station wagon called the Autoar PWO. This and a special machine tools division formed in 1951 would presumably help fund the continued development of the Porsche Cisitalia 360 and 370. (It is also important to remember that Cisitalia of Turin, suitably reconstituted, remained, run in part by Dusio’s son Carlo, and would continue to produce variants of the 202 and later the Fiat 850 until the doors finally closed in 1965.)

A Cisitalia based on the Fiat 850 and made by the Italian side of Cisitalia. Photo by Hugues Vanhoolandt.

One might assume that the successful design, development and racing successes of the 204 gave ex-motorcycle racer Carlo Abarth the courage to set out on his own. Dusio, after all, was now implementing his plan Argentina, so in this turmoil Abarth saw opportunity. With the help of Scagliarini, who provided the finances, Abarth established Societa Abarth & C.-Turin on April 15, 1949. Or so it was thought. But Lurani, after doubting that long established date, checked on it and found that the actual signing took place on March 31, 1949, with Scagliarini’s father Armando agreeing to back the new company, which was listed as being in Bologna, not Turin, for Bologna was where Scagliarini had his home. The April 15 date was remembered because it was on that day that the ‘Squadra Carlo Abarth” was launched for the press in advance of their entry in the 1948 Mille Miglia.

Abarth left Cisitalia with severance pay consisting of one Cisitalia D26, two complete 204s, and two additional chassis and moved them all to the new location at 10 Via Trecate in Turin. According to Nino Balestra, (Raisonne page 193, Abarth completed the construction of the other two 204s and in the next year four more were built by Abarth.

Dusio was now operational in Argentina, and by 1950, he was allowed to export the Grand Prix car, fifty 202 Cisitalias and four ‘sports’ cars to the Autoar factory in Buenos Aires. The four ‘sports’ cars are not clearly defined, but probably were 204s that remained with Cisitalia after Abarth left. The Argentinian 204s begin another story.

Sources

Cisitalia, Catalogue Raisonne 1945-1965, Balestra, De Agostini, Automobilia 1991

Un Sogno Chiamato Cisitalia, Mario Simoni, A&G 2004

Works Driver, Piero Taruffi, Temple Press, 1964

La Sport e I suoi artigiani, Curami/Vergnano, Giorgio Nada

Forty Years of Design with Fiat, Giacosa Automobilia, 1979

Abarth, Catalogue Raisonne, 1949-1986, Automobilia, 1986

Abarth, the man, the machines, Lucianno Greggio Giorgio Nasa, 2002

Abarth Buyer’s Guide, Pete Vack, VelocePress, 2003

We at Porsche, John Bentley, Doubleday, 1976