Don’t try this at home! A suggestive photo published by Volvo to illustrate the advantages of semi self-driving cars. Experts think that even before 2020, the combination of adaptive cruise control and autonomous brake systems will allow drivers of cars in the premium segment to cruise along in convoy, without having to pay attention what is happening in front.

Part 1 of ADA revealed a long history of attempts to create a self-driving automobile, while Part 2 discussed the political, social and legal issues confronting such vehicles. In Part 3, Gijsbert-Paul Berk considers the needs and fears of the marketplace.

Li Shufu (Li), Chairman of the Chinese Zhejiang Geely Holding Group (Geely and Volvo), has confided in an interview with Chengdu Business Daily (CBD) in February, that his company has as goal to produce fully autonomous automobiles by 2020. This may be a reasonable goal if China does not have to deal with the complex politics and legal systems in place in Europe and the U.S.

Back in Europe, Carlos Ghosn, head of the Renault-Nissan alliance, declared at a recent meeting at the French Automobile Club in Paris, “Cars that drive themselves can be on the roads four years from now, provided red tape does not get in the way. The problem isn’t technology, it’s legislation, and the question of liability that goes with these cars moving around … especially who is responsible once there is no longer anyone inside.”Look sir, no hands!

As Ghosn and others have pointed out, one of the first hurdles now is to get the permission from governmental authorities to test and to use such cars on public roads. Earlier this year, at the initiative of Germany, France and Italy, the UN Convention on Road Traffic was amended. It now allows drivers to take their hands off the wheel of self-driving cars. However the new rules stipulate that the human driver be must able to retake control at any time.

A number of U.S. states have taken the lead in establishing practical guidelines for testing and driving autonomous vehicles on public roads. Nevada was the first state in the USA that officially regulated the operation by civilians of self-driving vehicles on public roads by law. It allows the testing of such vehicles under certain conditions. The test vehicles must be equipped with a black box-type device to store data from the autonomous system sensors, so that it’s possible to retrieve information from at least 30 seconds before a collision. During the tests the cars have to carry red license plates. Another requirement of the Nevada lawmakers is that the purposes of the tests must be disclosed to the state authorities, along with information on how the vehicles behave in different weather conditions. Furthermore autonomous driving cars must have at least two people on board, with one of them – if necessary – to be able to take over the control of the robots.

Swedish Volvo that has a reputation for making safer cars is now testing self-driving automobiles on public roads in its homeland. A photo like this illustrates the advantages of their future system. Imagine going on a dark and rainy early morning in heavy traffic to an important meeting and your ADA permits you to read and check the latest reports, while the system takes over the hassle of driving.

California, Florida and Michigan have also published more or less similar guidelines for testing autonomous vehicles on their public roads. Those of the Californian Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) will take effect on September 16, 2014. They don’t (yet) cover the operation of self-driving cars but only the criteria that must be met by manufacturers before a computer controlled test car is allowed on public roads. Just as in Nevada during such tests, a trained “test driver” has to be ready to take over control of the vehicle. While DMVs are making inroads, there are other industrial, fiscal, and social implications to deal with.

EU Politics and Lobbies

In Europe there is (as usual) a lot of discussion. It is a sad public secret that to get the member states of the European Union to agree on any major subject is very time consuming and complicated. Even within the many political parties that make up the European parliament, there are great differences of opinion. And there is a strong lobbying effort from the car manufacturers in France, Germany, Italy and Sweden to get on with legalizing the use of self-driving cars, because they don’t want to lose out in the competition.

At the Geneva Motor Show Nissan unveiled an autonomous-driving version of its 100% electric powered Leaf. This ultimate political correct ADA will possibly soon get competition. At the same show the Swiss tuning specialist Rinspeed also presented plans to transform the electric Tesla into a self-driving car. But there will be no speeding in an ADA.

ADAs don’t speed

Many European politicians will have fiscal and social considerations to bear in mind as well. In some EU countries, such as France and the Netherlands, drivers who exceed the official maximum speeds bring a lot of money into the state coffers. According to the French weekly Auro Plus, in 2012 the 4.047 electronically operated radar ‘flashers’ in France collected around 730 million Euros ($987 million). As their Return on Investment is very attractive, the French government has installed 180 more of these ‘tax collectors’.

The Netherlands newspaper Algemeen Dagblad published a forecast that recently increased traffic fines in Holland (including those for parking, using cell phones and other traffic offences) will this year exceed 1.070 million Euros ($1,447). A major part of this money comes from fines for exceeding measured speed limits since the introduction of so called ‘section control’, on the motorways connecting major cities. But in theory, and probably in practice, autonomic driving cars will keep strictly to the speed limits. Can you understand the dilemma for the governments who have to balance their budgets? Who wants to kill a goose that lays such golden eggs?

Go Cabbie Go

Another worry is the social unrest self-driving cars may provoke; ADAs may mean a significant loss of driving jobs. Most major European cities still remember the recent fierce protests and strikes by the taxi drivers against the introduction of the Uber system. As is well-known, Uber promotes ordering chauffeur driven private cars by smartphone and the strongly regulated ‘regular’ taxis companies and their drivers consider this unfair competition. The loss of employment of all the taxi, bus, and lorry drivers that may occur due to the widespread use of self-driving vehicles is certainly another real nightmare in many countries, particularly those that already have a high unemployment rate.

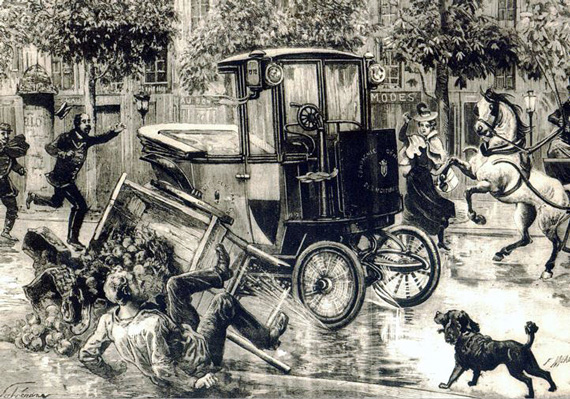

Cabbies, selfies, safety, circa 1899. This drawing of an ‘involuntary’ self-driving car was made in Paris and dates from 1899. Electric taxicabs (fiacres) were then considered to be a great technological leap forward; much cleaner and safer than horse-drawn carriages. However, as the driver (seen running behind the stray machine) forgot to cut of its electric power supply, this electric Krieger car went off by itself, hitting a handcar and creating panic.

Safer than the human?

Data from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration show that 95% of all car accidents in the U.S. are due to driver error. Sebastian Thun, a robotics expert working on the Google project, believes that ADAs could reduce the accident rate by 90%. Back in 2010 Google claimed that its autonomous cars had been extensively driven and tested over 160,000 miles (257,495 kilometers) without a single accident (although they admitted that one of the cars was involved in a pile-up caused by a human driver).

Robotized systems can also fail. This became painfully clear last November in Japan during a well-publicized demonstration, when a Honda CX-5 SUV, equipped with a Smart City Support Brake System (SCBS) had an accident. The SCBS is a driver-assisting system designed to avoid front collisions at relatively low speeds (19 mph / 30 km/h). The car crashed into a barrier especially erected to show the effectiveness of the technology. Japanese news media reported that both people in the car, a sales man and a prospective customer had injuries. So, will it be necessary to introduce new laws for self-driving cars?

Google attracted a lot of attention for the possibilities of autonomous-driving cars with their video on YouTube showing a blind man using a self-driving Toyota Prius.

Back seat drivers hold the key

Lawyers in some European countries argue that since the changes in the UN Convention on Road Traffic, it is not even necessary to introduce new laws for running self-driving cars. They see no juridical obstacles, on the condition that the base vehicle is homologated (conforming to the EU Type Approval) and the equipment does not interfere with the driver’s vision or keeps the driver from interacting fully with the vehicle. If the car complies with these criteria, it must be allowed to be driven on public roads, even with the self-drive system fully activated. As long as there is a person with a driving license on board, he or she will be held responsible in case of an accident or traffic violation. They also believe that insurance should not be such a problem either. The ‘compulsory’ car insurances in most countries of the Euro zone have third-party liability clause that cover both the driver and the owner against financial risks. As is the case with other expensive after-market equipment, the value of the self-drive system has of course to be declared to the insurance company. They may accordingly increase the insurance premium.

U.S. Liabilities

Thomas Simeone, a personal injury lawyer in the US interviewed by Carinsurance.com, thinks that when there are more autonomous vehicles on the road this will have consequences for the liability insurers of the car makers. Today we see one driver suing another, and then we could see both drivers sue the manufacturer for faults in the robotized system. Admittedly, the fear about product liability and its financial consequences is in particular an issue in the U.S. not only for American manufacturers but also for others who sell their cars on American soil, as Toyota can witness. In Europe this is not such a point. In 1992, Ford was hit with more than 1,000 product liability in suits in the United States against exactly one in Europe.

Next, is there a market for the ADA and will it take the fun out of ‘driving’?