Story by Roberto Motta

Joe Nastasi on the 33TT Stradale Giro d’Italia

As we have previously recounted, Joe Nastasi was born in Messina Sicily in 1948, migrated to the U.S. and worked his way up to becoming the U.S. Lamborghini importer. Nastasi also did well in a variety of other endeavors, allowing him to become an active collector and vintage racer. He became interested in Alfas after purchasing his first T33, s/n 11572.006. Over the years Nastasi managed to acquire other Alfa T33s from Autodelta; the 33/2 ‘periscope’ of 1967, and the 1977 33 SC12. Nastasi, as well as being a businessman, is also a great mechanic, and always personally oversees the maintenance of its cars with which he participates in the most important events reserved for classic cars.

Joe recalls the day when he first saw what he calls the ‘Alfa Berlinetta Stradale Giro d’ Italia.’ “One day, when I went to the Autodelta to meet with Carlo Chiti, I saw this beautiful car, the 33TT Stradale. I didn’t know much about the car, only what had been published by the newspapers of the era, but in my eyes it had a peculiar charm; in addition to being an Alfa Romeo, it was unique and entered only one race.”

Nastasi made it clear that obtaining the 33TT Stradale was not easy; everyone who knew of the car wanted it, including ex-Autodelta mechanic Marcello Gambi. He won out in the end. Gambi recalls that “When it was abandoned to Autodelta, I thought I’d buy it, but the competition with other collectors was too high, so in the end I had to bow out.” Nastasi claims that “When I bought the car it was not in perfect condition, because after the ‘Giro’ it had been abandoned.” No doubt the restoration would require an expert on the 33TTs.

As we have seen in Part 1, Alfa Romeo wanted to celebrate the victory in the World Constructors Championship by exploiting the strong media impact that would have emerged from the presentation of a new super sports car, derived directly from the world champion Alfa 33TT. The idea was therefore to participate in the Tour of Italy with a car that, as provided by regulations, was to foreshadowing a prototype series. For homologation, it was necessary to build a car that had an engine already used in a production car. For this reason it was not possible to use the 12-cylinder car engine because it had never been used, or at least approved for road use, so the old V8 was resurrected. According to Jean-Claude Andruet, Autodelta had none on hand anymore until a mechanic recalled seeing one in the attic at Autodelta. This was then used in the Giro car.*

Alfa Romeo had previously made a small series of 18 33 based street cars designated the Stradale T33. The production car s/ns began with 75033.001 for the prototype and ended with 75033.113. The 33TT Stradale was given the number 75033.114. But there had also been four additional Stradale concept car chassis built, and they were numbered 75033.115, 116, 117, and 118. With this operation, the 33TT Stradale became the 19th Stradale built.**

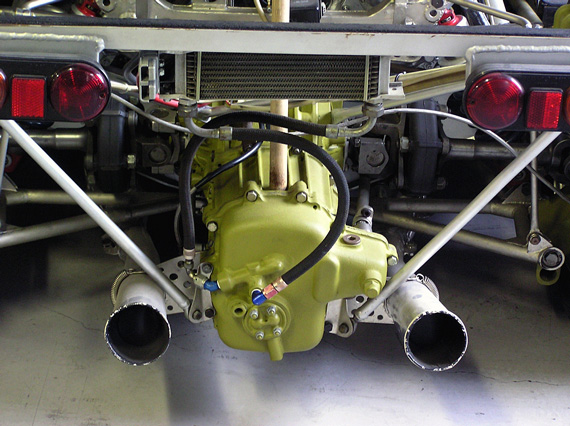

Despite this, the car was built with the tubular frame of 33TT-12. “The front suspension,” explains Nastasi, “remained practically the same construction scheme of TT12: in fact, it is identical to that of the 33TT-12 frame 07 that I have in my collection.”

At the rear, having replaced the flat 12 with the V8, it became necessary to change back to the old suspension used on cars with the V8 engine, and the addition of new set of longitudinal struts.

The use of the V8, was also characterized by a 5-speed transmission + RM, and provided the possibility to quickly change the gears simply by removing the end of the transmission. The engine used on the car was a type V8 115.04, in practice the latest evolution of the engine used on 33 during the 1972 season. “Thankfully, my friend Marcello Gambi decided to take on the restoration of the 33TT Stradale.

“During 2001, I attended the Intereuropa Cup at Monza. Initially the car felt really good, then in the course of the events the engine began to have oil pressure problems and forced me to retire with a broken engine. Later, I decided to personally inspect the crankshaft. During the reconstruction of the motor, I changed the lubrication system.

“I believe that one of the biggest problems that caused the V8 engine to fail was inadequate lubrication. In fast corners, the Alfa system allowed the lubricant to centrifuge: in practice, at certain times, some parts of the engine were not perfectly lubricated, in particular the connecting rod of the nearest to the flywheel. As a result the bushing began to suffer too much stress leading to the breakage of the crank. With the new system I realized, this problem has been successfully resolved, and I we had no more engine failures.

“Another modification is the introduction of a suspension setting that better for a racing car, which meant lowering of the car. Originally, the car was equipped with a higher trim to accommodate a competition that also included roads open to traffic. It had been developed to take part in an event that was more like a rally than a race.

“Finally, I deleted all the ‘ballast’ which was in the car to keep the weight within the rally regulations. It had three lead plates weighing a total of 45 kg, positioned in the passenger compartment under the seats.

“Currently the engine has been updated to the track version, and is capable of delivering about 500 hp.”

Nastasi concluded our conversation by saying: “In addition to being unique, the ’33TT-Stradale’ is a fantastic car, a thrill to drive and gives a lot of pleasure.”

The expert’s opinion: Marcello Gambi

Marcello Gambi is one of the most quoted of Alfa Romeo restorers racing, thanks to the great experience gained professionally over the years Autodelta.

“I started working at Autodelta when I was little more than a boy,” he tells us. “I acquired my experience on racing cars and started working in 1966 on the famous GTA. In the workshop and at the races, I worked on all the cars produced at Autodelta including those of the historical 1975 and 1977 World Championship of Makes. Throughout my professional career at Autodelta, I worked in virtually every department as an engineer, frame builder, electrician etc. including the development of engines for the nautical world and the cars entrusted to sporting customers. Of course, I also followed the development of the 33TT Stradale and I was part of the car’s service team during the Tour of Italy.

“Later, I opened my workshop and I went out on my own. Nevertheless I always kept in touch with Alfa Romeo, and have done a lot more work for the Alfa Romeo Museum.

“I believe that the 33TT Stradale was a great machine, but perhaps the engine was not suitable for road use in a rally where the engine must be able to provide power even at a low 1000 rpm. This engine was fine on the track, where the revs could be turned up.

“In short, this ’33’ was a bit tame, but in its DNA remained a track car. Although fewer horses were declared, the car had 460-470 hp at 10,000 rpm with a maximum torque at 7800 rpm, a speed which was a little higher than to rally cars.*

“The ’33TT-Stradale’, could have had a future, but unfortunately it was shelved immediately, as has happened with other rally cars produced by Autodelta such as the Alfetta GTV 8 cylinders.

“The thing that we disliked was that it was necessary to wait for Alfa management to start the project, and every time we had a winning car, management policies slowed the development or interrupted it entirely.

“For example, the 8-cylinder Alfetta; I followed the debut of this car in the Rally of Piacenza, where although it broke the gearbox in the first test, it proved to be competitive. When it became clear that it was a winning car, and to be defined by industry newspapers as the ‘anti Stratos’, it was stopped.”

We asked Gambi what was it like working for Autodelta in those years…

“It was fine, there was a lot of work to do, but there was also a lot of satisfaction and we were a very close team. We were also worked well with the drivers, as they had established a special relationship with the mechanics. Drivers often clashed with the engineers, but the relationship with us was more fraternal“.

Then with a smile Gambi says, “The ‘master’ was Chiti. It was enough to do what he said. Chiti was not one who gave much space to young engineers. The last word was always his, but it is undeniable that he was an engineer’s engineer.”

*For Andruet’s perspective of the problems with the Stradale V8, see “Tipo 33, The Development and Racing History” by Peter Collins and Ed McDonough, page 144.

**See complete Stradale s/n list, “Tipo 33 page 208”

Related Articles: