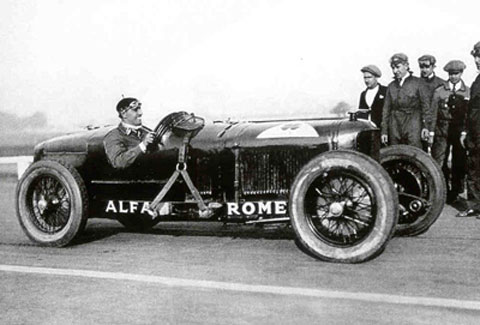

The first Grand Prix Alfa Romeo and the father of all modern Alfas.

The Great Ancestor Part II

Alfa Romeo P2, 1925-1930

By Nicholas Lancaster

Who is Nicholas Lancaster? Author of a new history of Brooklands for Shire Books, Nicholas Lancaster (UK) has been interested in motor racing history since the age of twelve. Recently he has contributed several articles on Alfa Romeo history to the AROC (UK) Magazine and has written two articles on Alfas for VeloceToday in the past.

Color Photography by Roberto Motta and thanks to the Automobilismo Storico Alfa Romeo Centro Documentazione (Arese, Milano).

The 1925 season began at the end of June with the Grand Prix of Europe, held that year at Spa. The only opposition came from Delage. The V12 engined cars were now fitted with superchargers and fully competitive. There were changes on the driver front as well. Ascari and Campari remained with Alfa Romeo, but Wagner had joined Delage alongside Divo and Benoist.

He was replaced by Count Gaston Brilli-Peri, an aggressive driver who relied on a whistle to warn slower drivers of his approach! For 1925, a change in the regulations prohibited the carrying of riding mechanics, although the cars were still required to have two seats.

The engined-turned instrument panel, the wooden steering wheel, the graceful curves constitute classic Grand Prix art.

Unfortunately the Delages all retired from the race, leaving the Alfa Romeo team alone on the track. Later Brilli-Peri also retired with a broken valve spring but the race had been an impressive Alfa Romeo demonstration with Ascari leading home Campari. Sadly, tragedy was only weeks away.

The next event was the French Grand Prix at Montlhery. The entry was stronger, with Delage and Sunbeam present, but by now the Alfa Romeos were the pace setters. During the race Ascari cleared off into a dominant lead, only to lose control in light rain and crash fatally. Although Campari inherited the lead a decision was taken to withdraw the rest of the team, allowing Delage to score a hollow one-two victory.

Ascari’s car, # 2, is shown in the 1925 Belgian GP where they ran

with the twin spares fitted. Credit Automobilismo Storico Alfa Romeo Centro Documentazione (Arese, Milano).

The final race of the year was the Italian Grand Prix at Monza. Delage decided to give this a miss, but new opposition appeared from across the Atlantic. Two straight eight powered Duesenbergs were entered for leading American drivers, Tommy Milton and Peter Kreis. Another American star, Peter de Paolo, the reigning Indianapolis champion, was entrusted with the third P2.

For the final race of the two litre formula, the Alfa Romeos were still being improved; the tails were shortened by 150mm, and vents fitted to allow air to escape from the rear bodywork.

The race was won by Count Brilli-Peri from Campari, but not before the Alfa Romeo team was given a fright by the speedy Duesenbergs. Fortunately for Alfa Romeo both of the American entries ran into problems. Kreis crashed early in the race and Milton had gearbox problems. He still managed to finish fourth. Guest driver De Paolo ran as high as second in his P2, despite commenting that the handling of the Alfa Romeo was poorer than his usual Duesenberg, but he eventually dropped out of contention with carburettor trouble, finishing fifth.

The result meant that the Alfa Romeo team claimed the title of World Champions and a wreath was added to the Alfa Romeo badge to commemorate the achievement.

For 1926 Grand Prix racing changed to a new 1.5 litre formula and the P2 was now ineligible for international Grand Prix racing. The cars were sold off. Two went to former team drivers, Campari and Brilli-Peri. Count Bonmartini bought another, while a Signor Nasturzio had one converted for road use. A Swiss enthusiast named Kessler bought one which he used to take several hillclimb victories in 1926, including the prestigious Klausen event. But the Campari car was the most successful P2 in private hands, winning the Coppa Acerbo at the daunting Pescara circuit in 1927 and 1928, amongst other good results.

The wreath was added to the

badge after winning the 1925

World Championship.

In the autumn of 1928 Campari sold the car to the motor cycling champion Achille Varzi. He shared the car with Campari to finish second in that year’s Italian Grand Prix, then won at Monza, Rome, Allesandria, and Montenero in 1929, to become Champion of Italy. Meanwhile the company had modified Brilli-Peri’s car, boring the engine out to 2006cc. In this form it won the 1929 Circuit of Cremona recording a maximum speed of 138.7mph along the 10km straight where Ascari had reached 121.8 in 1924. .

In South America, Vittorio de Rosa behind the wheel of an Alfa P2. Its arrival in Argentina created a sensation. Read review of Alfa Romeo Argentina. Courtesy Bertschi/Iacona

The P2’s success in 1929 persuaded Alfa Romeo that it would be worthwhile modernizing some of the cars for the following season. They bought back cars from Varzi and Brilli-Peri and also repatriated a car from Argentina for the new Scuderia Ferrari. All the cars were bored out to 2006cc and the supercharger was now fitted in the more efficient position between carburettor and engine. That and other modifications raised power to 175bhp at 5500rpm.

To match this increase the chassis were either rebuilt or replaced. They retained the 8 ft 8 inch wheelbase but the track was increased to 4 foot 6 inch front and rear, using axles from the 6C 1750 sports car. The rear springs were now placed outside the chassis rails; and braking and steering systems based on the 1750 Gran Sport were also fitted. The bodywork was substantially modified with a new radiator similar in shape to the 1750. The bonnet was modified to match. At the rear Jano modified the fuel tank with an unusual longitudinal slot to house the spare wheel that recalled the 1914 Grand Prix Peugeot.

For 1930 Varzi joined the Alfa Romeo works team, but not before he had repeated his 1929 win at Allesandria with his own P2. He then sold the car back to the factory where it was rebuilt, on condition that he could drive the car in the Targa Florio. However the team had second thoughts, considering the 1750 more suitable for the twists and turns of the Madonie circuit. But Varzi insisted the agreement should be honored and eventually the management gave way. The main opposition came from Bugatti, winners for the last five years, with a strong team lead by Louis Chiron.

Old Grand Prix cars got a new lease on life as sports cars, as Varzi proved when he won the 1930 Targa Florio. The win, however, was the P2’s last victory.

Old Grand Prix cars got a new lease on life as sports cars, as Varzi proved when he won the 1930 Targa Florio. The win, however, was the P2’s last victory.

At the start Varzi went straight into the lead but the rough roads caused the P2’s spare wheel to break away, cracking the fuel tank. Varzi was able to refuel while his mechanic, Tabacchi, carried a spare fuel can in the cockpit. Fearing that Chiron must now be leading the race Varzi continued at full speed. But Chiron had problems of his own, having briefly gone off the road, and Varzi was back in the lead by the final lap. Now Varzi’s P2 began to run out of fuel. Tabacchi leaned over the back of the car and began to refuel from the can while Varzi pressed on. Fuel spilt over onto the exhaust pipe and ignited. That didn’t stop Varzi. As Tabacchi beat at the flames with his seat cushion, Varzi kept his foot down and crossed the line the winner after almost seven hours of racing.

It was an epic victory but also the P2’s last. In Italy Maserati were providing tough competition and the Alfas were being stretched to the limit of reliability in order to keep pace. The team persisted with the P2 for another couple of months but the best results were a win in the ‘Consolation’ race at the Monza Grand Prix meeting and third place at Brno in the Grand Prix of Czechoslovakia. Afterwards the P2 was retired by the factory after seven glorious seasons of racing.

Nathan Lancaster’s work on the P2 was published in the AROC of UK, in an expanded version. You can join the AROC at this website.