Review by Pete Vack

There were old books and magazines with photos and drawings of the Alfa B.A.T.s spread out across the table when the mail arrived. Along with the bills was a box from Dalton Watson. What could this be, I wondered, as I cleared a space for it.

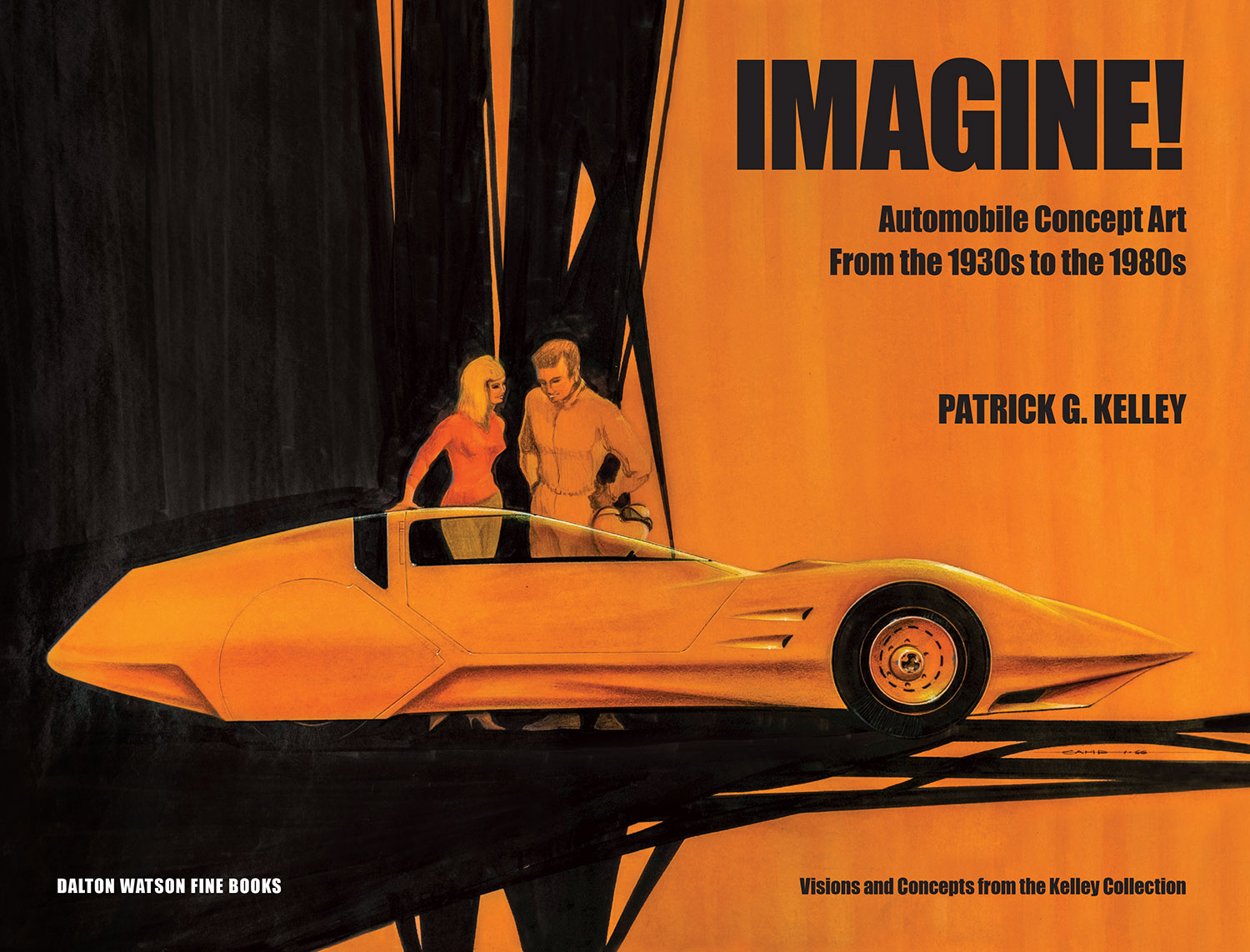

It turned out to be a book on the art of American stylists, entitled Imagine, Automobile Concept Art from the 1930s to the 1980s, by newbie author Patrick G. Kelley, full of dramatically beautiful stylists’ sketches in color. On the table, in those very same old and increasingly musty periodicals from 1949 on, were many such examples of the art of advanced styling from the studios of GM, Ford, Chrysler and more. And of course, the B.A.T.s we were researching were famous concept cars themselves. How timely, then, was this arrival. I knew very little about the creation of concept car art in America although our shelves burst with books about the Italian designers. Author Kelley had profiled and exhibited what we might refer to as “America’s Scagliones,” or “America’s Michelottis,” (which rolls off the tongue and title easier). So the book was opened and read with enthusiasm. What could I learn?

I had never seen a photo of MacMinn, yet here he was in Kelley’s newbook (pardon the pun), shown teaching a group of art students at the Art Center School of Design in Pasadena.

A few pages into Imagine and germane to our research into the three B.A.T. concept cars, was a photo of Strother MacMinn*, who also plays a role in our series on the B.A.T.s this week. The main content consists of over 235 unique images of would-be lost automotive art in Dalton Watson style (with layout by Jodi Ellis), the images are large, (219 mm by 290 mm) elegant, with near perfect reproduction, and the subject matter arranged not by date or styling studio, but by artist. I was impressed and thankfully, Kelley had done his homework and included a brief bio of each of the 87 artists wherever possible. This truly brought the visuals alive – without it, the artwork would have had far less meaning.

The artists therein were the Michelottis of America, being as creative and as imaginitive as their Italian counterparts. But working for GM was a bit different than working for Alfredo Vignale or Nuccio Bertone but in what ways? MacMinn himself jumped out here from the pages of our research, and in the February 1957 Road & Track wrote, “Italian artists have often been noted for their cultural ability to combine swept and moulded [sic] forms with great taste and refinement, and just as often enjoy the opportunity of presenting their designs on excitingly lithe chassis.” This was surely a difference between the Italians and their American counterparts, who may have contributed to a large-scale concept car mockup or in fact a complete, running, car but probably only incidentally. Scaglione’s concept cars (see https://velocetoday.com/interview-with-giovanna-scaglione-part-8/ ) often went from drawing to complete metal fabrication upon a running chassis, with the artist on hand! Others, like Zagato’s Ercole Spada, drew and created in the same shop as the panel beaters. What might have U.S. based artists thought of that arrangement. Said author Kelley, “American car designs were very much controlled by the committee, by the bean counters and by strongly opinionated heads of the corporations.”

Taking into consideration the known experiences of Tom Tjaarda and Tom Meade, both Americans who worked as designers in Italy but in the latter half of the 1960s, we still wondered what the American Michelottis thought of their European counterparts. Did they ever meet to discuss new directions in styling? Were the Italians alone in their scope of freedom? How did they differ and how were they alike? Did American free-lance artists have a chance to submit their work to the design studios before or after they worked for them? Or could they freelance, like Michelotti? What were the problems incurred in a corporate environment? “The emphasis on design esthetics in Europe was much more pure and naive in a way, but that purity would lead to some of the greatest automobile designs ever created,” said Kelley. But it was not within the scope of Kelley’s book to answer these questions, but to provide the basis to ask them and to plant the seed for future work on the subject.

TransAtlantic Style

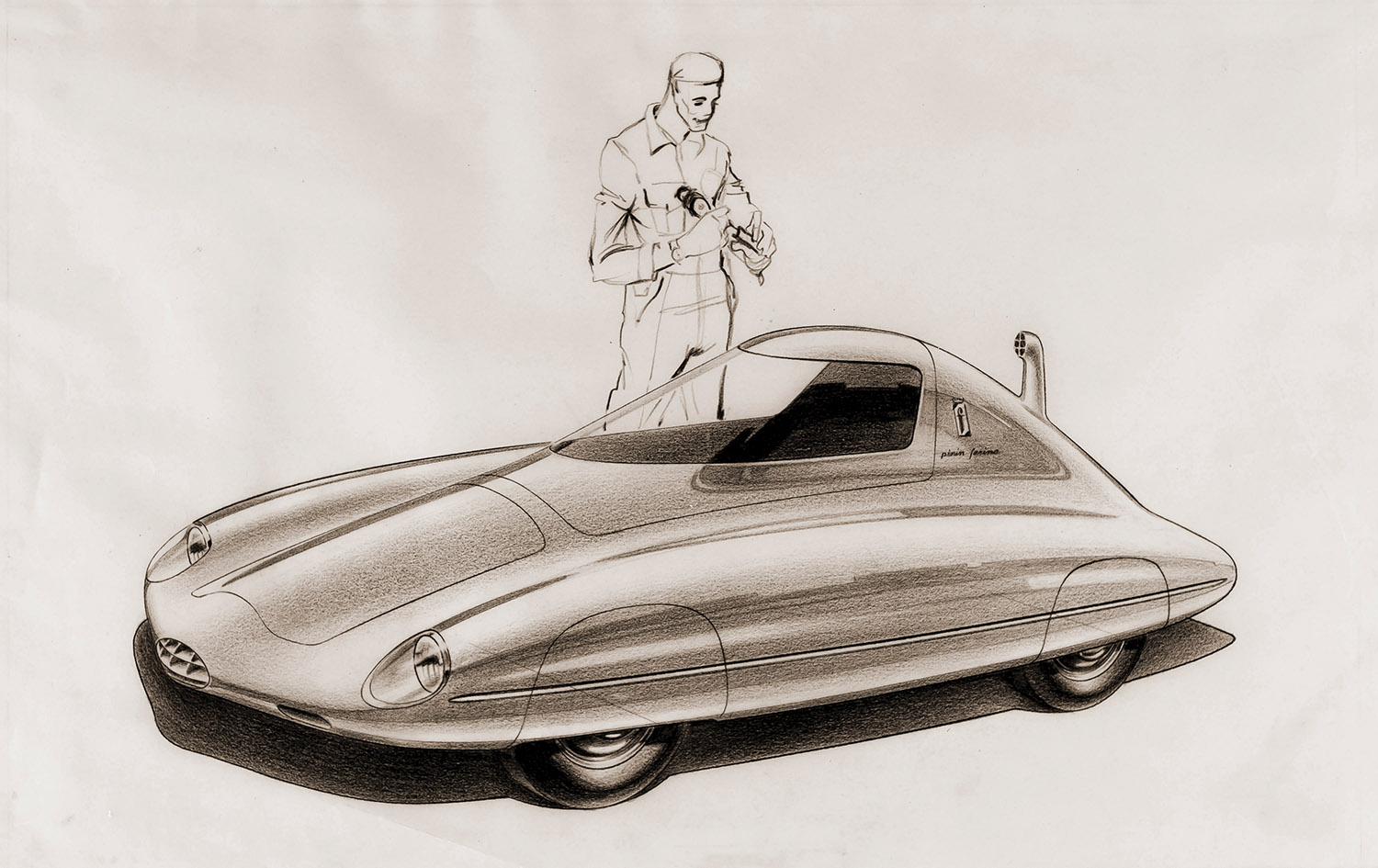

Naturally I wondered if these largely unknown and unheralded stylists allowed the Europeans to influence their art and if this ‘Transatlantic Style’ so ably defined by Donald Osborne in his book of the same name, would be seen in some of the many drawings accumulated and presented in this new book. Paging through Imagine, it didn’t take too long before we spotted examples of Italian influence on design, and vice versa.

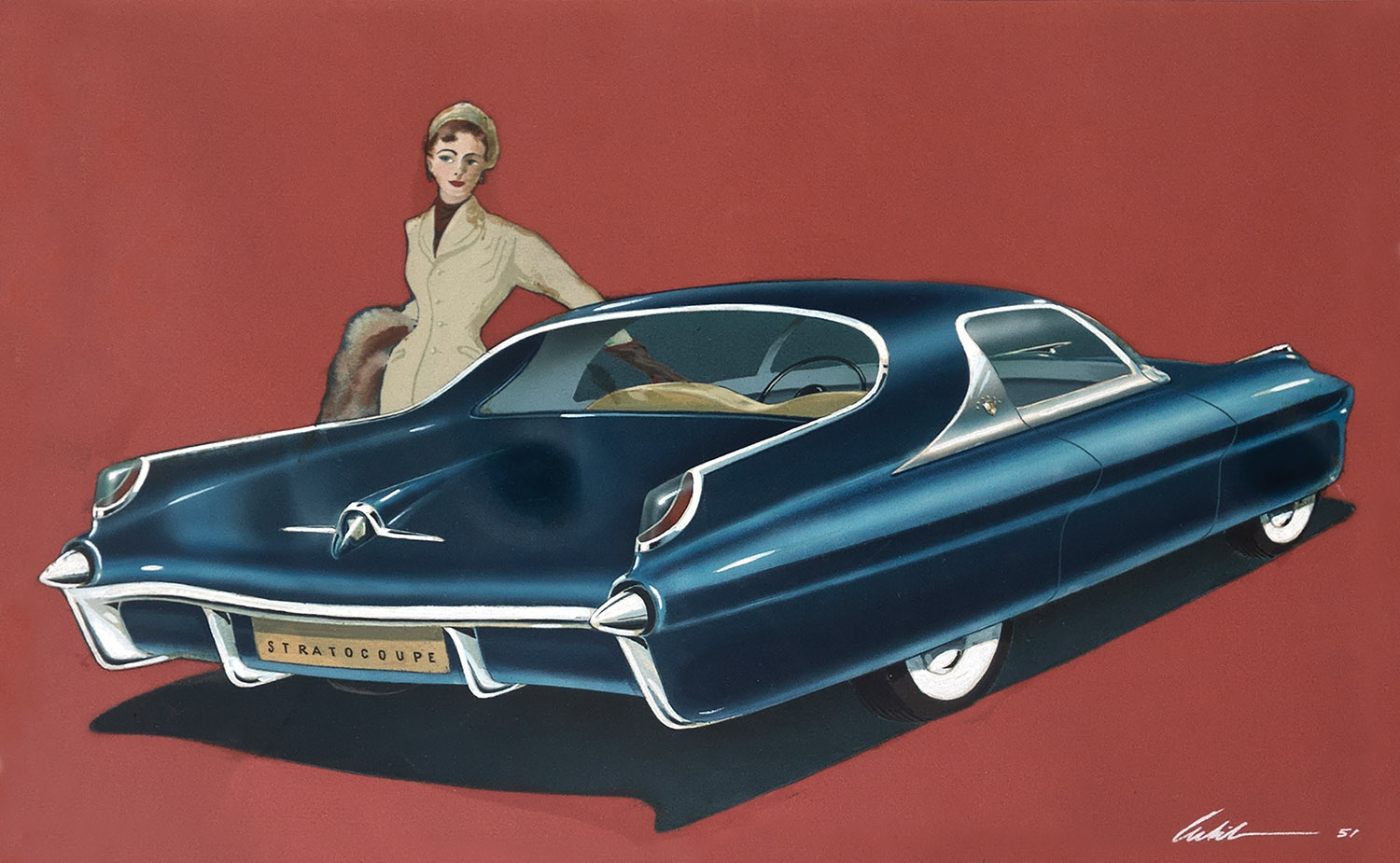

Richard Arbib keyed on Pinin Farina’s flying buttresses for this ‘Stratocoupe’ concept car dating from 1959.

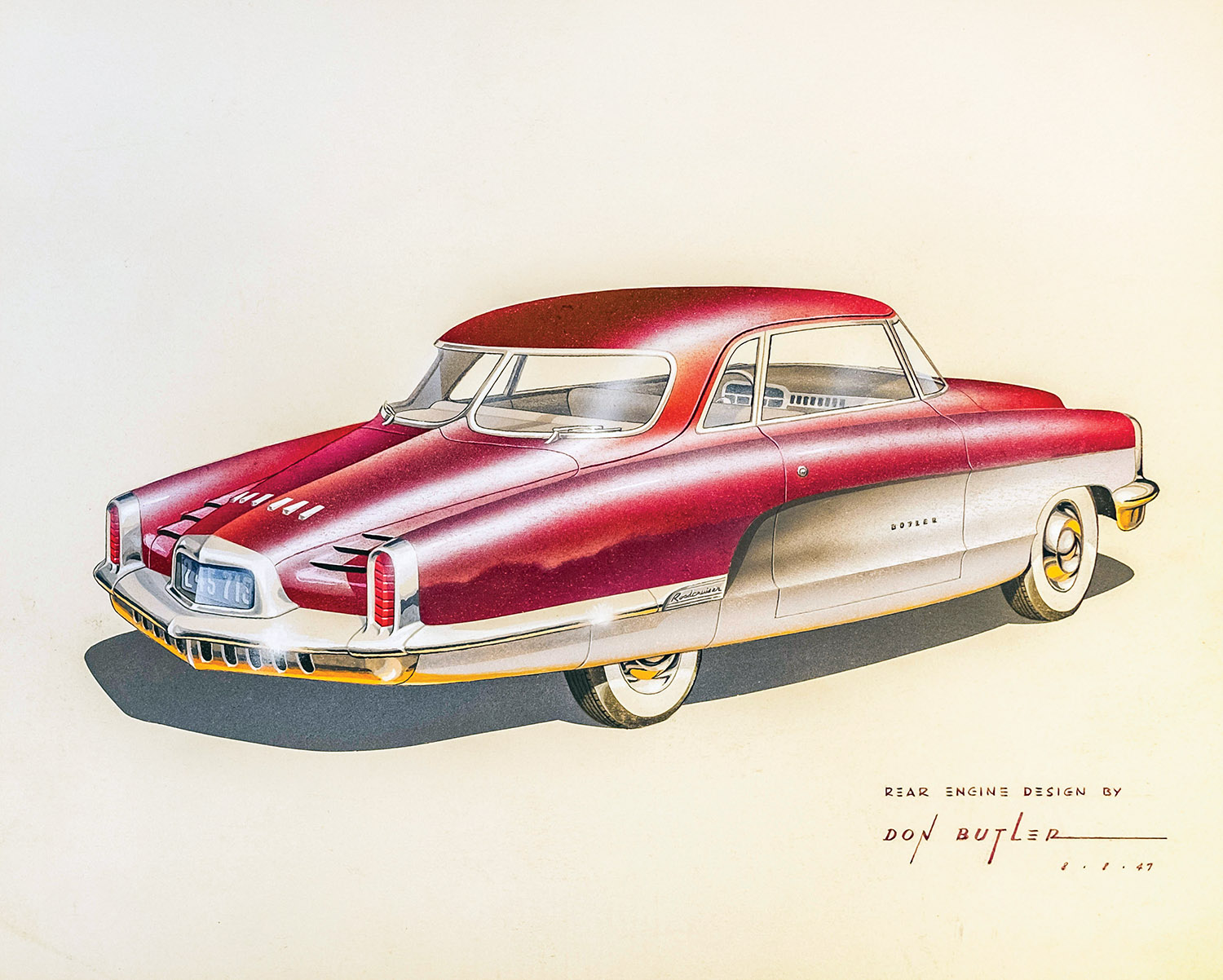

And the influence went both ways. Hudson-Nash stylist Don Butler sketched out an idea for a Loewy-Studebaker-like design. One thinks naturally of the Studebaker until one notices the slight dorsal fin, and one is immediately reminded of B.A.T. 7. But this sketch is dating from 1947, some seven years ahead of B.A.T. 7.

The dorsal fin effect is marginal here and does not continue between the two rear windows, and some wonder if it is actually a design element? So, does this sketch really pre-date B.A.T. 7 and the 1963 Corvette? Don Butler art.

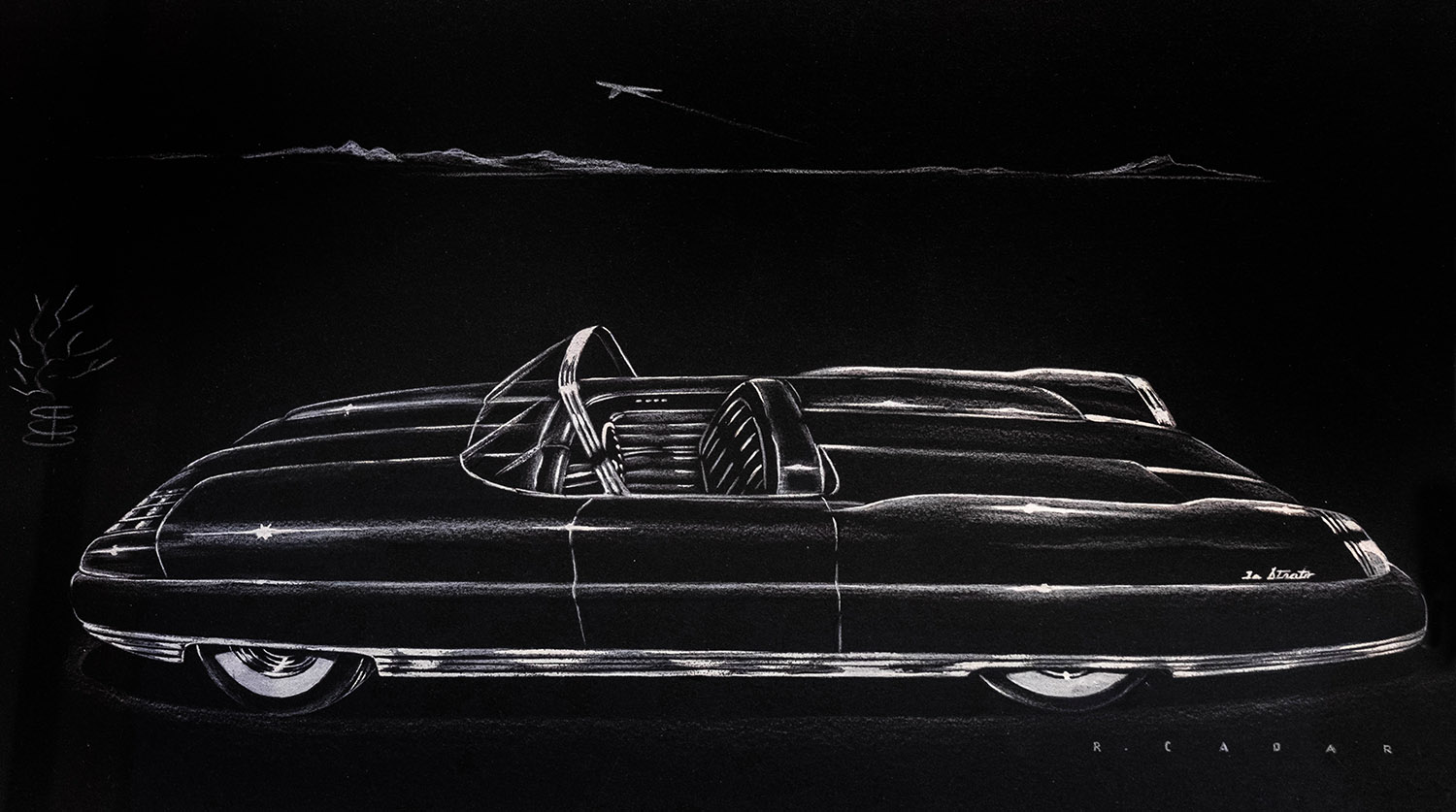

Robert Cadaret was also ahead of the B.A.T. curve. Put a lid on this 1952 drawing and out pops the 1955 B.A.T. 9d. Of course, themes are not only cross-Atlantic but perhaps memes of the era as well. Notably, Cadaret worked for GM and assisted with the design of the 1955-1963 Corvettes.

One has to use a bit of imagination here to envision a fastback coupe but the lines are much like B.A.T. 9d. Robert Cadaret art.

Imagine, however, is so much more than our myopic look at trans-Atlantic comparisons. Kelley relates how he came to collect this artwork and the story is really quite alarming. Always interested in cars, he was strolling through the San Francisco Art Deco show and spotted some incredible automotive art. He befriended the dealer, Leo Brereton (without whom the book would not have been possible) bought a few pieces and his collection began to grow.

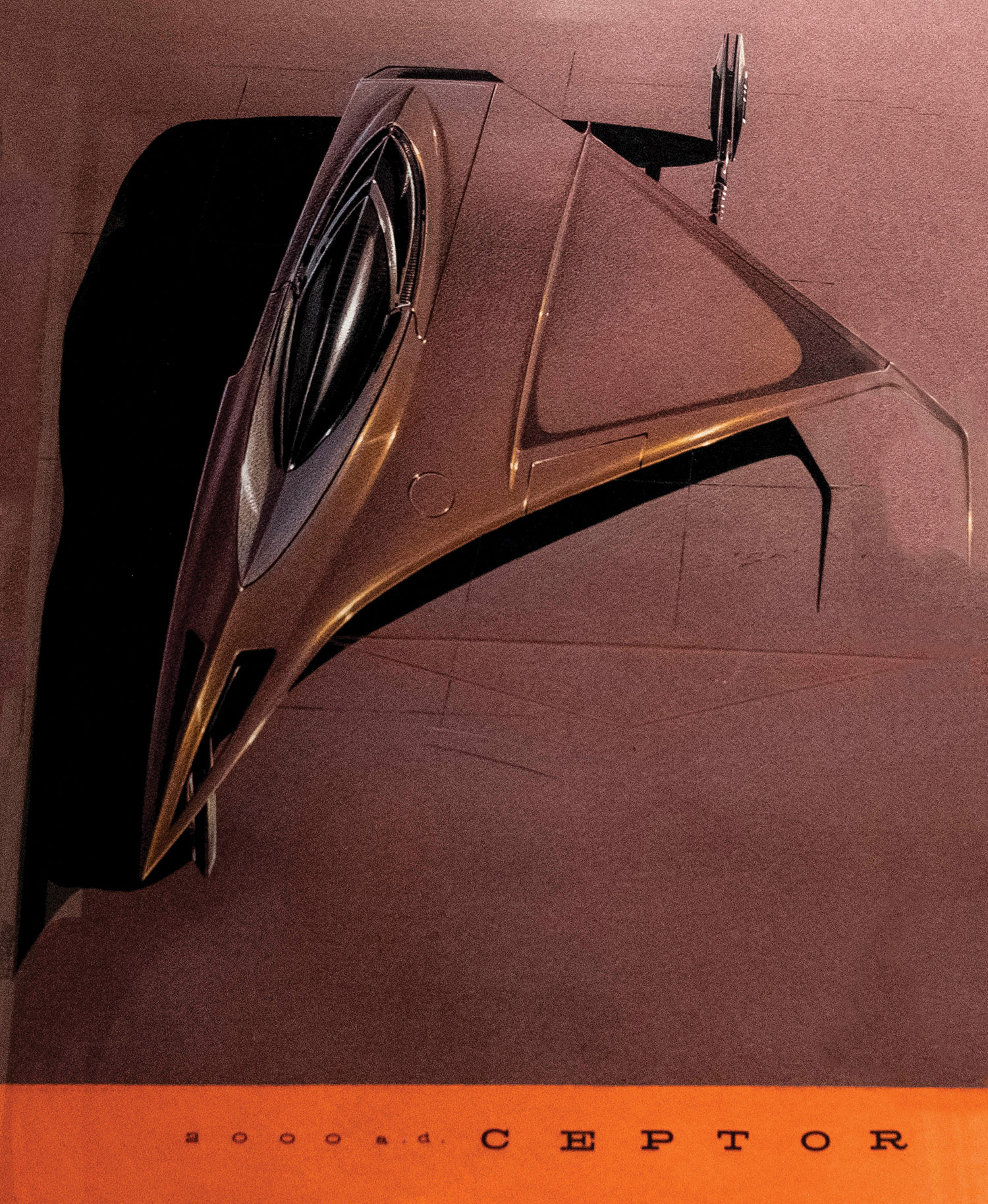

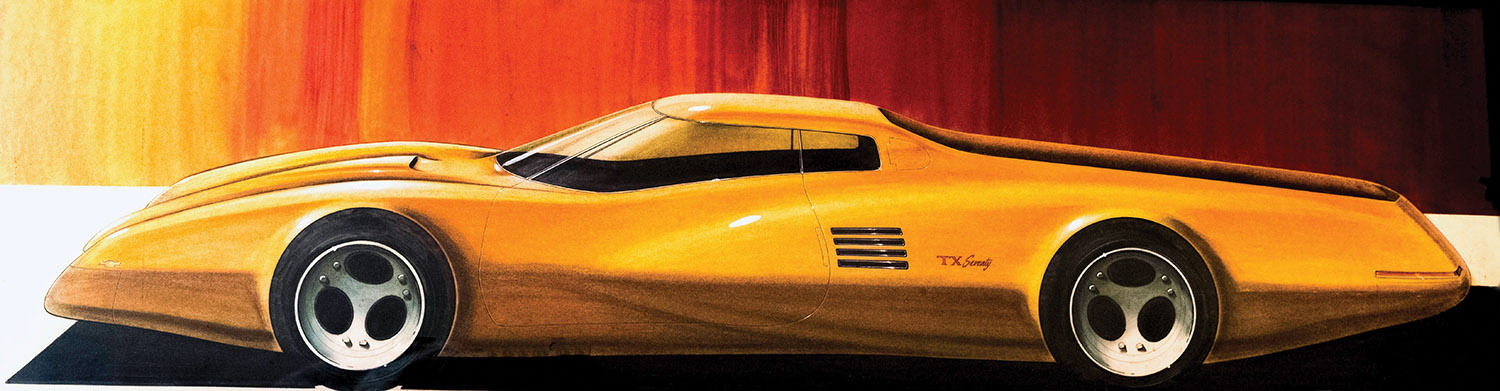

And imagination is what it is all about. From the 1960s, futuristic thoughts from artist Ken Vendley

But where were these minor masterpieces found? What happened to them along the way? Did the various studios keep the drawings over the years or were they just discarded? If they were kept by the studios or discarded, how did some end up in the basements of cold Detroit houses used as insulation? The story behind the drawings is as fascinating as the art itself. Suffice to say that over the years Kelley has found and saved hundreds of concept car drawings done in pencil, pen and ink, gouache/marker on board, and a variety of other mediums that perhaps would have been forever lost. Kelley has done us all a favor in being able to publish, in full color, these impressive, though fleeting, concept car drawings.

Kelley lists the materials and medium of each of the drawings, and the size, as found, as well. They are not miniatures,most measure at least 22 inches across and roughly 17 in height. We assume there were paper vellum rolls, torn off to size, drawn upon, saved or discarded as the stylist’s idea was transformed into a visual currency. Indeed, Kelley has a chapter about super-size drawings called “The Big Pieces” which are usually 56 inches in height and 20 inches in length, and used to decorate the studios themselves. Either size would be a handful to collect or store. I asked Kelley about this. “Many of the images are framed, many are in flat file cabinets but few are folded or rolled…they are mostly very old and were never meant to last for a few days let alone many years, so keeping them flat and free from moisture is a key – some are mounted on artboard, or created on board, many of the vellum pieces are quite fragile and are lightly mounted on backing board.” To be sure, if you decide to collect these, make sure you can display or store them properly. They were lost once, don’t let it happen again.

Kelley’s book is devoted to artists like Syd Mead, who worked for Ford, then himself, US Steel and movies such as Blade Runner. Here is an example of his dramatic art, year unknown.

We sincerely thank Patrick Kelley for putting all of this together. It is a fascinating look at a lost art and hopefully will prompt further efforts that incorporate automotive designers from all over the world during that golden era – perhaps into one large multi-cultural volume!

Author Patrick G. Kelley

ISBN 978-1-85443-306-0

Publication Date August 2019

Page Size 219 mm x 290 mm. Landscape. 323 pages. Hard cover

Price US$135/£110. Signed and numbered limited edition of 100.

US$90/£75. Regular edition.

The book may be purchased from www.daltonwatson.com

*MacMinn discovered a few interesting facts about the B.A.T.s in his discourse with Bertone in 1989 LINK and in 1955, was duly impressed by the BAT 7, LINK saying it was “true elegance in design”. Furthermore, MacMinn is familiar to our VeloceToday readership for his photography. LINK https://velocetoday.com/strother-macminn-and-the-bugatti-atlantic/

Raymond Lowry – the best!

Yes…Raymond Loewy was definitely one of the best!!

Ant Alex Tremulis in the book?