By Patricia Lee Yongue

Photos Courtesy of VintageMotorphoto

Guillon, Garfield and Plessier are

rewarded for their efforts.

In May and June of 1925, Renault took the world’s twenty-four hours record at Montlhery, with Ellery Garfield and Robert Plessier at the wheel of the 5500 pound open-bodied car.

Garfield’s team completed the twenty-four hours in what he called “absolutely a standard stock car, save for the increased rear axle ratio [2:1],” at an average of 88 mph.

24×100 Round Two

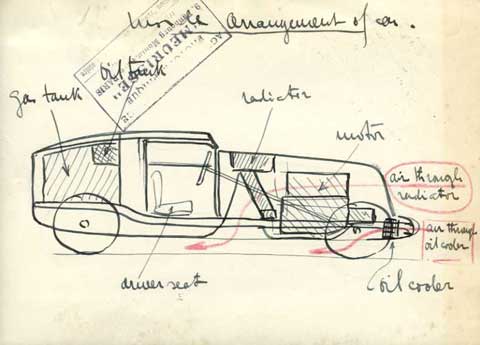

Not surprisingly to Garfield, that twenty-four hours record did not last long. The British Bentley claimed victory three months later, having upped the ante to 95 mph. This defeat raised the hackles of Louis Renault, who demanded Garfield regain the record. Garfield not only had Bentley to worry about, but he had earlier written to Wills that he thought Panhard and Voisin were also about to make a run for the money. Garfield got to work and made several major changes. He wrote Wills that the “boss” had given him “nearly a free hand” this time, and so he “rebuilt” the car according to his own ideas. The first modification he decided upon was to close the sheet metal body and make it as narrow as possible, some thirty inches wide.

Garfield’s sketches for the record breaking Renault 40.

The frame was wood over which he stretched a moleskin fabric. The four-seater now became a “much more comfortable” single-seater, with the steering wheel positioned at dead center, giving the driver equally good visibility to the left and to the right. Garfield also “fitted rear view mirrors inside the car,” making it “possible to see all four wheels and to thus see how the tires stand up.” But the car was over fifteen feet long and weighed slightly over two tons in running order. Its engine was still 9.1 liters. It had a nearly 40 gallon fuel tank.

Interior detail with much engine

turning decoration in evidence.

Bentley on their heels

Garfield knew that the Bentley engineers were busy, too-they wanted to be the first to do the twenty-four hours in over 100 mph on the average-but he figured that they had hit their stride at 106 mph. Besides, he knew that no car could retain its maximum speed for twenty-four hours.

As Renault’s good luck would have it, Bentley started up four times but failed due to a series of valve, valve spring, transmission, and other problems. On the fourth attempt, the car ran off the track and “smash[ed] through a fence.”

Front view of the Garfield Renault. Note oil cooler above axle.

24×100 to Renault

But despite Bentley’s ill luck, the road for Renault was not smooth. A factory strike and a fire that “destroyed completely the tire stock department” delayed Garfield’s work by at least a month. At two p.m. on July 9, 1926, however, he set out with Robert Plessier and Paul Guillon and in the 40 CV Type NM completed the 2,590 miles of twenty-four hours at Montlhéry “without a single mechanical problem.”

Tires were still a bother, however. The drivers made twenty-five stops for tire changes-twenty-four of the stops for all four tires; the other for two rear tires. This annoyance forced Garfield to make drivers’ shifts one hour instead of one and a half hours, and the planned maximum speed of 116 mph was reduced by one or two mph. But the Renault drivers accomplished what Bentley’s could not. Their average speed was 107 mph. En route, they also picked up six other records.

Rear view illustrates lack thereof.

Garfield left Renault again on November 30, 1926, possibly to work as an independent. In July 1927, he filed a patent application in France, for a method of constructing flexible car bodies. He filed a patent of addition to this patent in October. In June 1928, he filed a patent for the same process in both the United Kingdom and the United States.

Although they are conventionally impressive for the detail they provide in the design and engineering of the 40 CV, less conventionally the letters reveal what appears to be Garfield’s effort to help Wills out of the mire of a dying company at the same time he was trying to follow Louis Renault’s orders that Renault regain the twenty-four hours record it had lost to Bentley. For example, in 1925 he asked Wills if he had made use of the suggested layout he had sent him for a balanced crankshaft.

Maybe Garfield remained homesick and wanted to assist Wills also in order to have a place to return to. Wills had always been interested in racing, and perhaps Garfield, who commented on the American failure to participate in the records runs and in twenty-four hours road races like Le Mans and Francorchamps, was encouraging Wills to think in terms of developing a race car as well as a passenger car. Wills had, after all, helped Henry Ford with his early racing program. Wills paid great attention to detail, a practice Garfield felt most American auto manufacturers deferred.

Little known, less heralded, the first car to average more than 100 miles per hour for 24 hours.

Garfield also had shown Wills, when the latter came to Paris, Louis Renault’s personal car, and Wills expressed interest in the adjustable reclining back, using leather straps spanning between the seat and the back at both sides of the seat. (Adjustability was obtained by a buckle and an array of holes in the leather strap.) This was a fairly common arrangement in European cars with lightweight bodies. Bugatti touring cars of the late 1920s-the T40 Grand Sport torpedo, for example-used this arrangement.

Whatever Garfield’s motivations, his efforts to help Wills were ultimately futile. Wills Sainte Claire went under in 1927. Garfield returned to Renault in May 1929, raced to a podium finish in an eight-cylinder Nervastella at Casablanca in 1930 and died during practice for the Tourist Trophy, near Belfast, Ireland, on July 11, 1930.

The author would like to thank Dale Lafollette of VintageMotorphoto, Dick Ploeg of the

Netherlands, and to Mr. Jean Barberousse of the Societé d’histoire du Groupe Renault.

Bibliographic sources include William Boddy, /Montlhéry: The Story of the Paris Autodrome, 1924-1960 /(1961), and Gilbert Hatry, /Renault et la Compétition: Les Folles Équipées /(1985).

Wonderful article ( but then I’m an unabashed Francophile) but the big question is ” Does the record Renault still exist and if so..where??” I want to see it. Does anybody out there know?

Thanks Pete for the most intresting web site. Phil

you can write that Mr GARFIELD was the husband of one of the wife surgeon in PARIS : mrs BRIAN GARFIELD ,the couple was on thetop society;

As to Phil Friday’s question: ” Does the record Renault still exist and if so..where??”

Yes and no, a copy of it on a more or less correct Renault chassis was produced by Jacky Pichon of Cleres, France. Eventually this car was added to Renaults historic collection and may now be visible in their works museum. The driver names are proudly displayed on it, but unfortunately not without misspelling the name as “Gardfield”.