Classic race car instruments and steering wheel design. Functional design with elegant execution to match the De Tomaso/Shelby P70 race car chassis. Photo by Dick Ruzzin.

By Dick Ruzzin

De Tomaso’s Racing Vision

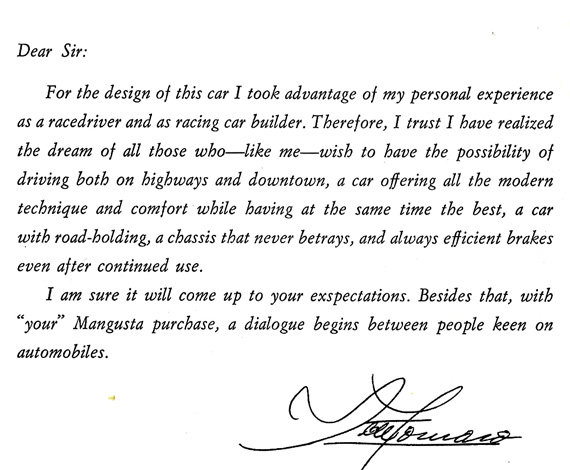

Included in the very small owner’s manual that accompanied all new Mangustas is a message from Alessandro de Tomaso himself. He makes a special statement to his customers, speaking to them very personally:

To our subscribers: Ignore the ‘comments are closed’ notice below as it is a software glitch; put your comments at the bottom of each article as before.

These statements describe De Tomaso’s genuine passion to build a car that would give the owner the unique feel and performance of a racing car for public roads, one that meets expectations and does not fail. It is true that a Mangusta with a well-tuned chassis performed very well against all popular comers in an early published Road and Track handling test. It was only bested by a purpose-built open wheel race car. De Tomaso’s words were boldly presented for all the world to see and they clearly showed that he was very committed to the performance of the Mangusta.

He did not, however, speak of its “look.” Little did he realize that the car’s ability to begin the “dialogue between people keen on automobiles” would be rooted in the design and appearance of the car, so much so that it would greatly overshadow its mechanical shortcomings. Although de Tomaso was known for a number of very innovative engineering concepts during his race car building career, he was criticized for not developing his ideas further. Instead, he left them to go on to new ideas that he found fascinating.

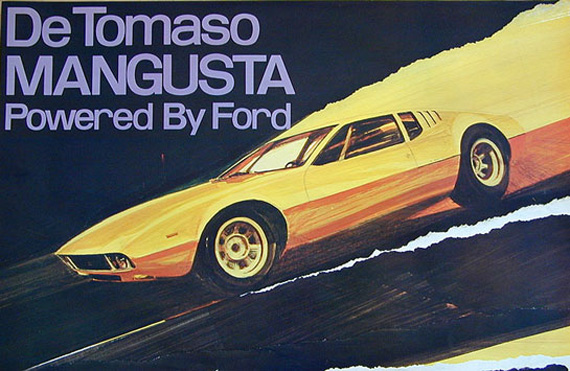

Emulating the then-preferred racing Grand Prix car layout, the Mangusta was conceived with longitudinal mid-engine architecture including popular racing components, including the renowned ZF five speed transaxle and the large aluminum Girling disc brake calipers. Both were then being used on Grand Prix and sports racing GT cars in competition.

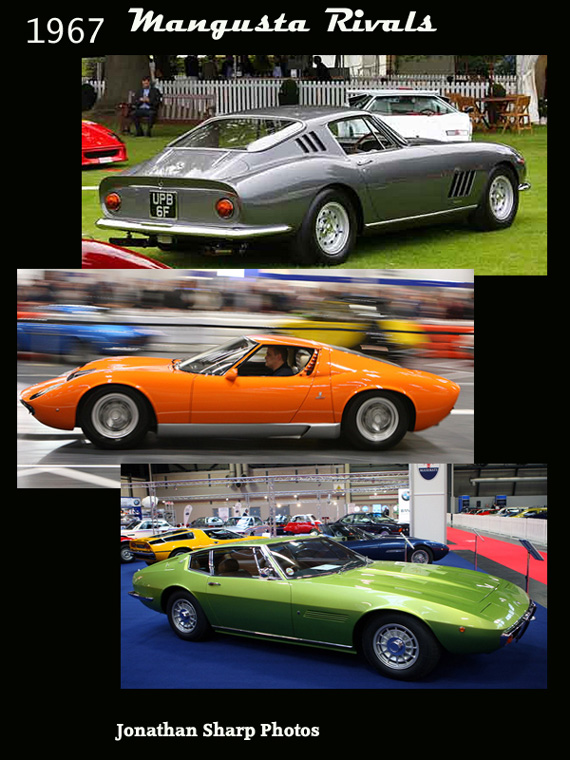

Introduced at the fall Turin show in 1966, the Mangusta was ahead of the competition and much less expensive that its only real rival, the Miura. Sharing much of the Ghia body hardware and the low-cost American engine allowed the Mangusta to be priced at a little over half of the Lamborghini Miura..

The Mangusta’s front suspension has welded tubular upper and lower A-arms, and in the rear four long trailing links with large tubular lower A-arms and upper cross car links. The factory-signed cast aluminum rear hub carriers with stub axles each have two large ball bearings sandwiched together in a light, compact unit. The front and rear suspension hardware is connected with Heim joints throughout, the same type commonly used still today in competition cars of all types.

The major suspension components and their layout combined with front and rear sway bars is classic race car suspension design of the late sixties and early seventies. At the time, this new mid-engine architecture had started to sweep through racing circles. The character of the race inspired Mangusta architecture came to match Guigiaro’s emotional and dynamic body shape.

Simple interior design reflects the simplicity of the exterior. Included is the classic shift gate and lever as well as the best Italian leather throughout. Photo by Daryl Addams

The interior is tight fore and aft. The Mangusta is trying to be a race car and most Italians fit in the car easily. Short, low, and wide, the car was cutting edge for the time both in engineering layout and aesthetic design. When the Mangusta was being sold in the sixties and early seventies there were race cars with the same longitudinal mid-engine architecture competing and winning on race tracks around the world. After introduction at the Turin Automobile Show in 1966 the De Tomaso Mangusta was rushed into production leaving some functional improvements possible, more than normal for even low production car programs of the times.

As we noted, the Mangusta body really does enclose a race car chassis called the P70. If you look closely considering the race car chassis, many aesthetic design choices, both interior and exterior, make sense. They visually confirm the race car character that de Tomaso desired. You can see it if you examine the instruments and the multiple pieces that form the steering wheel construction, the classic slotted shift gate, and the location and subtle style of the shift lever.

The most outstanding is the much misunderstood instrument panel. It is a vertical and flat piece of leather covered metal, like that in a race car with holes drilled for eight round gauges and seven toggle switches. Flat black suede covers the top panel and is designed to minimize reflections created in the sheer and steeply raked windshield.

The low wide front of the Mangusta and Giugiaro’s sheer and smooth form language was a striking new approach to car design.

The classically designed black Veglia Borletti instrument dials with blue-green markers and pointers, and flat black bezels and faces are the same as those found in many Italian racing cars of the era. The instrument panel presents a wonderful combination of mechanical and aesthetic harmony; the design is very understated, elegant and functional. The main interior focus as it would be in a racing car is the steering wheel. It is composed of high gloss honey-colored wood, black leather for the driver’s hands, and three smooth and thin satin finished stainless steel spokes. The De Tomaso “T” is machined into a subtle milled depression in its bolted metal center. The steering wheel’s mechanical design character is perfectly matched to the spirit of the Mangusta’s racing chassis. It is a work of art.

The finest Italian leather is used in all the other interior components, arm rests, door trim, seats, foot-well, and rear firewall coverings. All are also designed simply and in harmony with the exterior theme. The exterior air intake and exhaust openings are fitted with satin black steel wire mesh, an easily fabricated and lightweight material that is a favorite even today of race car builders.

The original prototype had exposed hinges for the two engine covers hiding the central spine under the skin. This was changed for production.

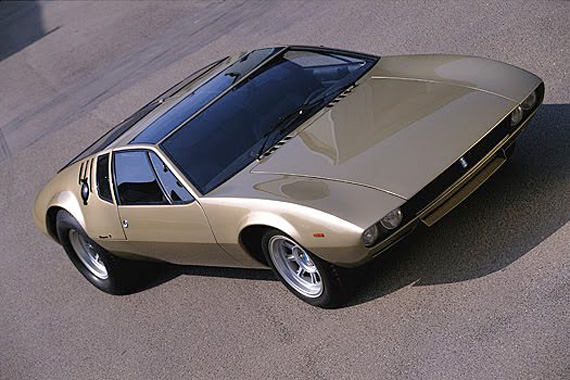

Most people, including astute automotive press and enthusiasts, have not noticed that the design of the gold prototype called the Ghia Mangusta first shown in Turin and the later De Tomaso Mangusta production cars are very different, although they share the same basic exterior design theme. Close examination shows that front and rear graphics as well as the instrument panel are different. The gold car also has slightly different proportions, a wider, thinner front and rear and rounder profile lines. The car is also a bit longer, with much bigger rear tires. A different, more trendy instrument panel design was also originally mocked up in the prototype for the Turin show.

The prototype design was skillfully transferred to the production car, of which 401 were produced. The rear tire size shown on a Ghia Studio drawing signed by Giugiaro are 255×70/15, visually much smaller than those on the gold prototype. The production car has even smaller tires, 225×70/15 with the same 185×70/15 tires in the front. The Mangusta was the first production car to use different size tires on the front than in the rear. Grand Prix race cars of that era have much larger tires in the rear. It is interesting to note that the Mangusta’s wheel openings and the volume of the wheel wells in the body are capable of fitting much larger and wider wheels and tires in both the front and rear than those released for production. Like mid-engine race cars, the Mangusta also has a wider rear tread than that of the front and the widest part of the car is the sheet-metal at the front of the rear wheel openings.

De Tomaso naturally sought the light weight that any race car must have, so the body’s front and rear compartment covers were shaped in thin aluminum sheet, then skillfully edge folded and pop-riveted to simple welded steel frames that carry the hinges. This fabrication technique has been used in the construction of race cars built in small numbers for many years.

Access to the engine compartment for normal maintenance is excellent. Both rear covers are held in place by four thirteen millimeter bolts that retain the central spine. Photo by Dick Ruzzin.

The public at large first saw the gold Ghia Mangusta prototype out in the world and running at the Grand Prix of Monte Carlo in 1967, seven months after its introduction in Turin. A large exterior black flip style gas cap had been added. The glass roof panel allowed the race spectators to see its very special and beautiful passenger, Princess Grace of Monaco, as the car made a demonstration lap around the race course. It was seen flashing past the balcony of the Hotel de Paris before the race started as de Tomaso used his public relations skills to present the race-inspired Mangusta to the European racing community. It was very well noticed as its appearance was a vision that thrilled untold thousands of racing enthusiasts from all over the world.

Designers that I worked with in Germany four years later who saw the car tour the track that day told me that the gold Mangusta was stunning. It was made even more so by the excitement of the race fans and the presence of the Grand Prix cars themselves. The contrasting blue sky, dark track, brightly colored flags and historic architecture made the speeding golden Mangusta stand out like a gleaming bullet. They regretted that they did not recall seeing Princess Grace.

Since the gold car did not have the final production details and we do not know what stage the production design was in at that time, we can only speculate that perhaps this Monte Carlo experience influenced de Tomaso and Giugiaro, causing them to direct the design to follow the race inspired mechanical architecture with race inspired aesthetic content more strongly. This could have resulted in the change to the final design direction taken for the steering wheel, instrument panel, and other details on the exterior like the black wire screens.

we picked out the colors and interiors for the 3 cars we sold new. biggest problem: front brake lockup, especially in rain. possibly unintended longevity feature: ignition point spring so weak that the car wouldn’t rev over 5100rpm

The brake lock-up problem apparently was borderline with stock tires, as you describe. The car needed a brake proportioning valve, in the front, to balance the tire and weight bias front to rear. One of those at a very low cost fixes it. Front heavy cars require a brake proportioning valve in the rear to achieve the same end.

Regarding the weak point spring, it may have been done on purpose if the original engine here in the USA had hydraulic valves. Floating the valves with a hydraulic cam can cause the valves to interfere with the piston travel, breaking valves and pistons in different levels of disaster.

DICK RUZZIN