By Wallace Wyss

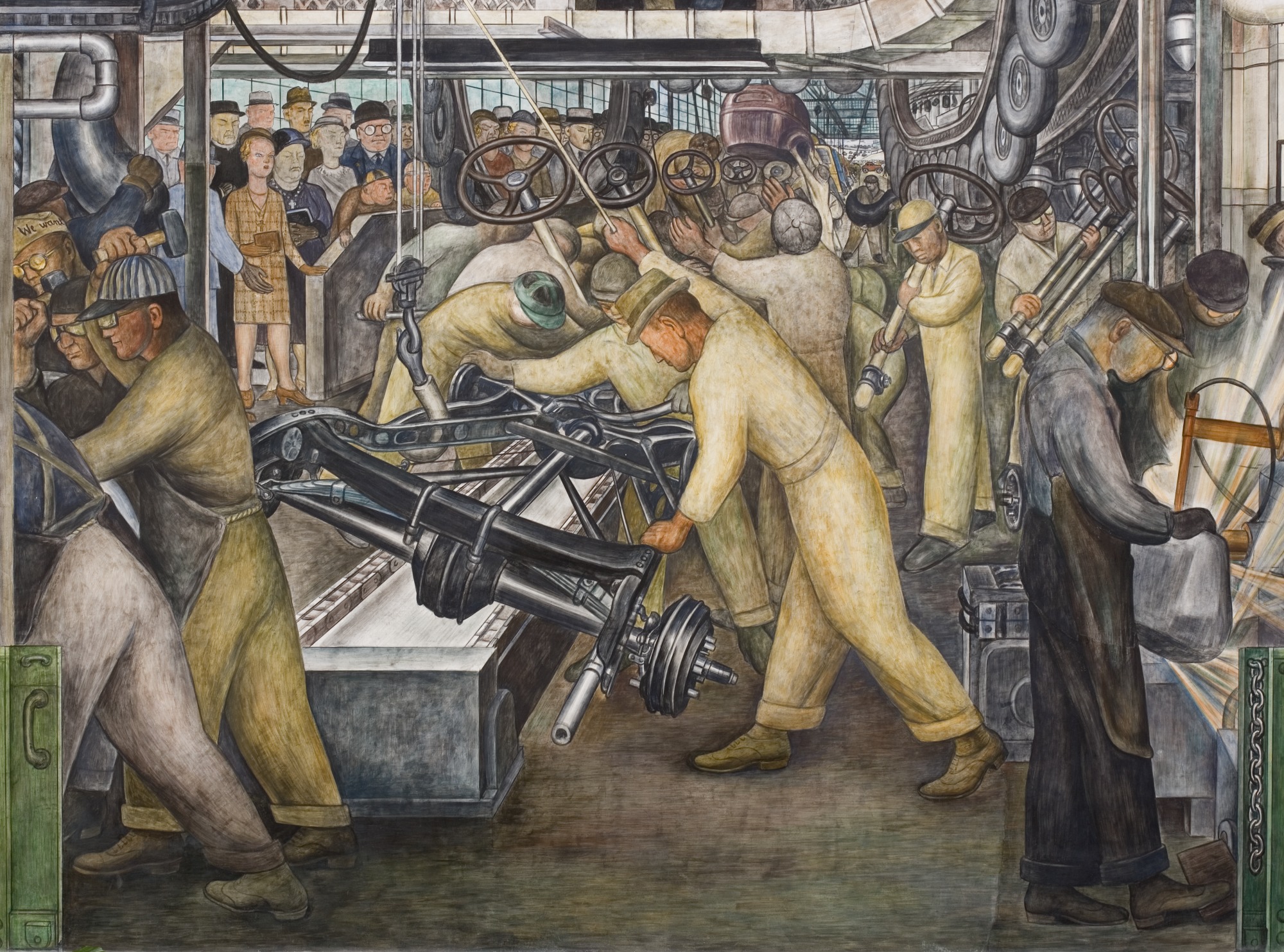

One of the greatest car paintings ever made is not, as one would expect, a single portrait of a single car. No, it’s a mural. And it isn’t just one mural on one wall, it goes on and on in room after room. And as you will see, it is powerful, evocative and controversial.

Commissioned in 1932 by Museum Director William Valentiner, the murals, collectively known as Detroit Industry, cover all four walls of the Garden Court in the Detroit Institute of Arts Museum, and number 27 in all. Bankrolling it was Henry Ford’s son, Edsel B. Ford, then president of the Ford Motor Company, who was trying in every way to escape the grinding pressure imposed by being the son of the most famous industrial leader in the world.

The artist was Mexican Diego Rivera, (1886-1957) who set up house in Detroit while he painted the mural, a job that took him eight months. By choosing to work in murals, he gave the public a chance to see artwork which they might not if held in private collections and galleries. He took commissions for the painting of murals because he believed by using (preferably public) walls as his canvas, he helped revive the mural as an art form in the U.S. Though he died more than half a century ago, he is still among the most revered figures in Mexico, both for leading his country’s artistic renaissance and bringing to the new world a fresh appreciation of the of the mural genre.

It is best to look at the murals in chronological order, starting with the east wall which depicts a baby in the bulb flanked by two fertility figures and fruits and vegetables indigenous to Michigan. Rivera liked to connect human endeavors to earth and nature. Every icon in the fresco cycle is meant to play off something depicted in another part of the room, such as the east wall’s agricultural symbols playing off the west wall’s technology.

A member of the Mexican Communist Party, Rivera was expelled in 1929 because of his suspected ties with the Russian politician/philosopher Leon Trotsky. Despite his leftist leanings, Rivera actually got on pretty well with Edsel Ford, the arch-capitalist who was authorizing a communist to do the murals in his auto plant. But, says art aficionado/historian Clyde Berryman, “This also brought Rivera problems of his own from the left who accused him of cozying up to capitalists, of being a ‘fake red millionaire.’” The relationship with capitalists did not go so well for Rivera with the Rockefellers, who commissioned him to do a mural at Rockefeller Center, but after it was done had it destroyed under pressure from those who said they were purveying Communist propaganda.

Rivera was given an open assignment for the Institute of Arts murals; all he had to do was reflect the development of industry in Detroit! Fortunately, there was one place in the world where the entire process could be witnessed; Ford’s nearby River Rouge plant. David Halberstam in his book ‘The Reckoning’ defined the plant:

“At its maturity in the mid-twenties, the Rouge dwarfed all other industrial complexes. It was a mile and half long and three quarters of a mile wide. Its 1100 acres contained ninety-three buildings, with twenty-seven miles of conveyor belt. Some seventy-five thousand men worked there… The process was revolutionary. The production of a complete car from raw material to finished item dropped from twenty-one days to only four. The Rouge was Henry Ford’s greatest triumph and with its completion he stood alone as the dominant figure in America and the entire developed world.”

Rivera and his wife Frida Kahlo, (a famous artist in her own right who had an affair with Trotsky) shot film footage, and took hundreds of photographs in their research at River Rouge. Notes Berryman, “Not unsurprisingly, Rivera’s murals remind me in style a bit like what Stalin ordered Soviet artists to paint when depicting the accomplishments of workers, farmers and soldiers.”

Although the Detroit frescos are primarily showing man and machine in an industrial landscape, there’s an undercurrent of social commentary in them; hints at the inequality between the capitalist entrepreneurs and the legions of workers who carried out the dream. But often it was no dream for the workers themselves. I know from my father, who, as a Swiss immigrant, worked on the line at the Rouge in the early 30s, it was not so pleasant. Henry Ford had hired a pugnacious gangster, Harry Bennett, to muscle workers who didn’t co-operate. Alas, I never asked my mother if she ever went to see dad working on the line, but I can’t blame her; decades later I walked through the Rouge but even then, there were noxious fumes and lots of noise.

Click to enlarge images

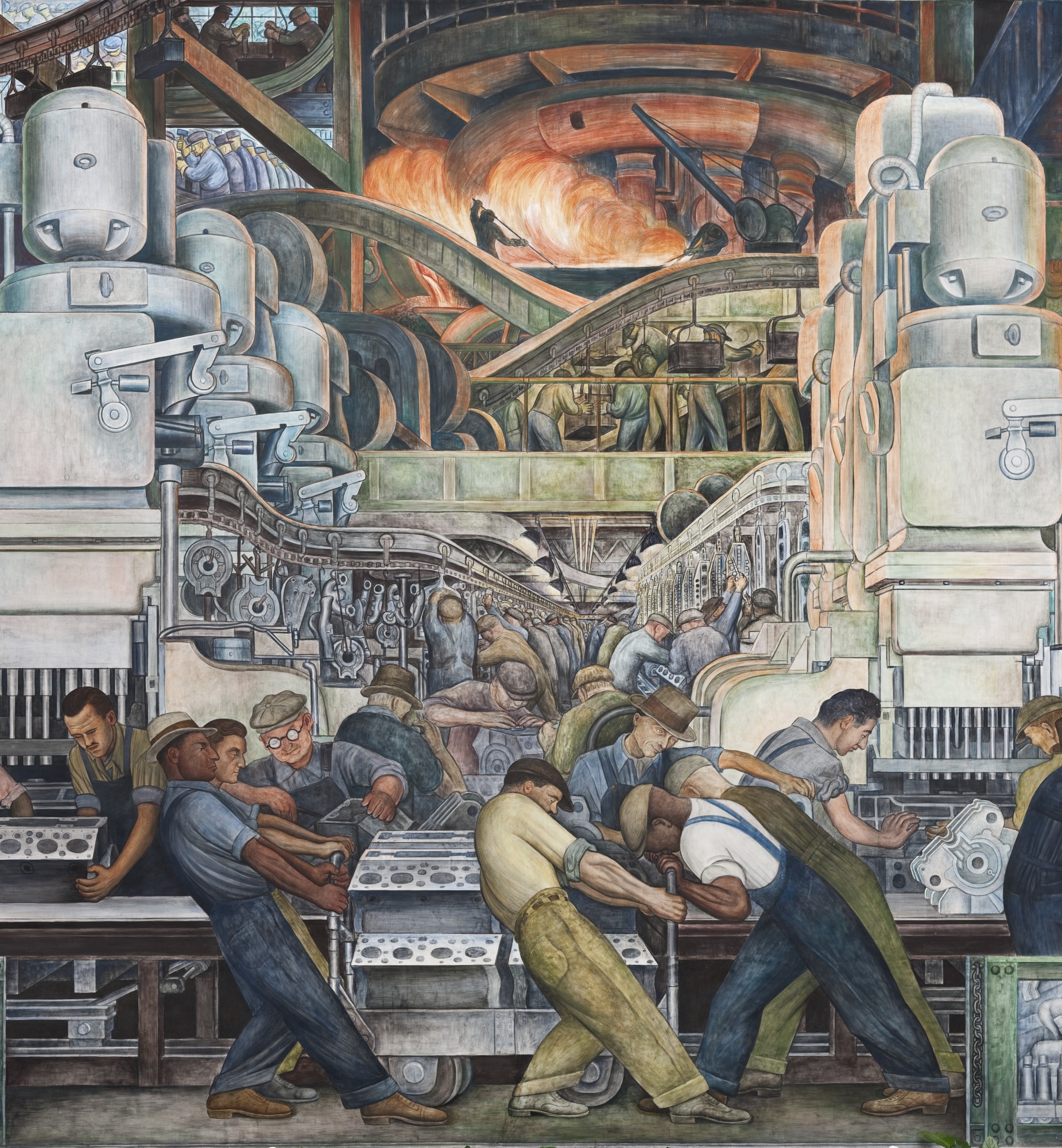

To study the process of automaking, Rivera and his wife toured the River Rouge factory, an amazing place where raw iron ore went in at one end of the plant and finished Model A Fords rolled out the other. At its high point, the work force numbered at least 75,000 workers.

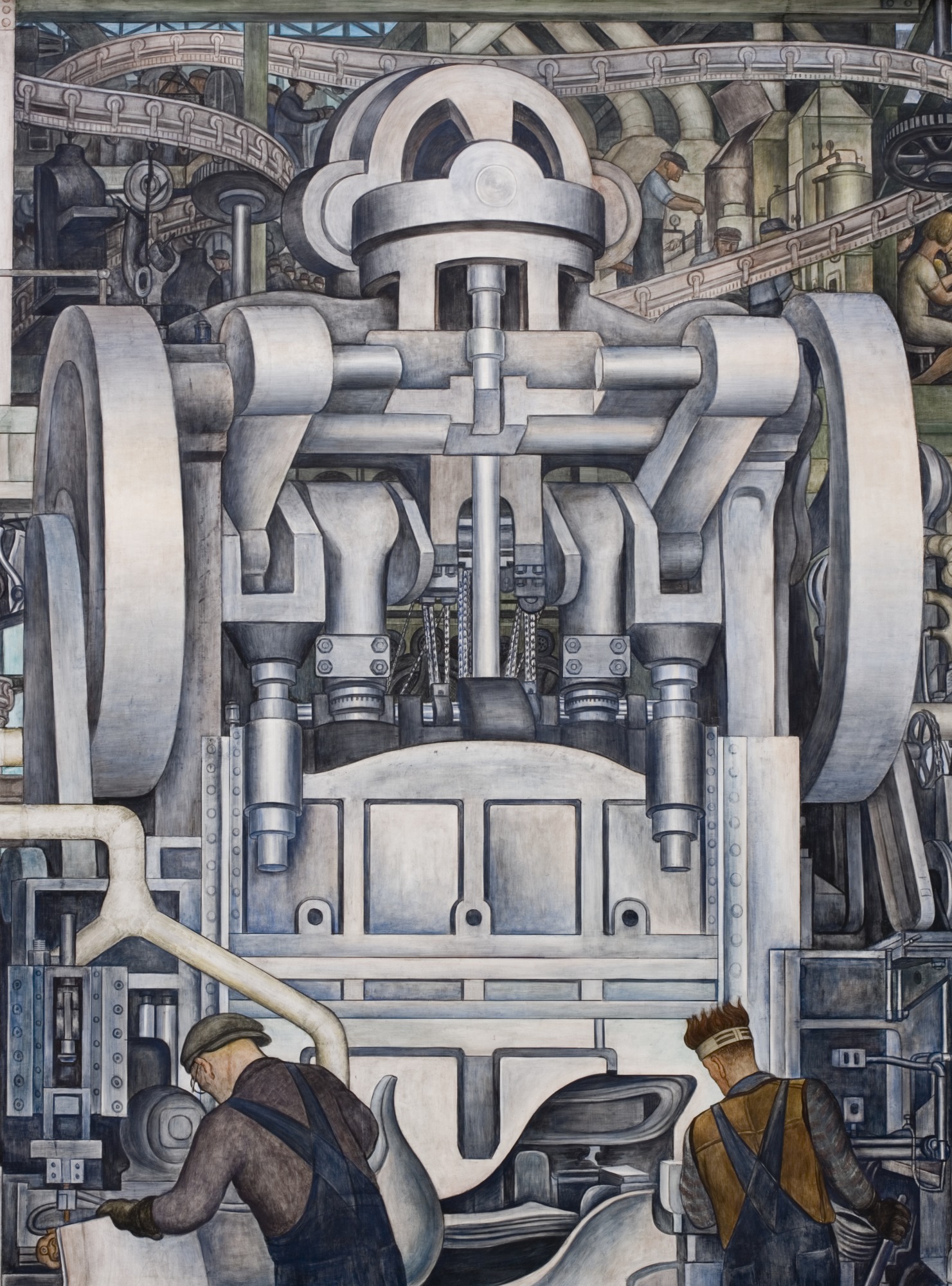

Here workers are dwarfed by the latest automotive manufacturing technology, a press that would create the sheet metal for a body in seconds. A powerful tool, a powerful image.

Although the Detroit frescos are primarily showing man and machine in an industrial landscape, there’s an undercurrent of social commentary in them; hints at the inequality between the capitalist entrepreneurs and the legions of workers who carried out the dream.

In the foreground some worker is using caustic chemicals. The symmetry of the workers in the back was a Rivera trope – Rivera was always orchestrating the workers in his paintings to create a harmonious composition, just like when he had depicted farm workers in Mexico. He also depicts a sense of camaraderie on the line, though personally I know from my father, who, as a Swiss immigrant, worked on the line at the Rouge in the early 30s, it was not so pleasant.

Rivera was conscious of his setting. He even painted particular topics on certain walls to enhance how they would look when the afternoon light came through the museum window; for example, showing the sunlight illuminating the fire in the blast furnace.

As in the Renaissance period, Rivera dutifully painted his patrons into the picture, having Edsel Ford and the Museum Director William Valentiner shown on the assembly line. Edsel is at left, looking a bit apprehensive.

Now that we are in the age of robot manufacture with images of advanced plants like Tesla showing not a human in sight, Rivera’s work becomes all the more poignant.

All images are courtesy of the Detroit Institute of Arts, USA / Gift of Edsel B. Ford. Copyright clearance for Detroit Industry handled by Bridgeman Art Library on behalf of the Detroit Institute of Arts.

I saw these murals in the ’80s and they have stayed with me since. I remember standing before them in awe. When this damn virus is gone I will go back.

Edsel Ford should be given credit here also as he was the real sponsor of the Diego Rivera murals and for also putting a significant part of his family history in his hands. Edsel Ford was also a co-founder of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City and the Detroit Institute of Art in Detroit where the murals are presented and the central works of great importance. During the depression Ford personally paid the salaries of those working at the DIA to insure it’s survival. He studied art and design, educated himself to be a designer and was very well versed in what musems had to offer in Europe and the USA.

Ford, much to his credit, prevented the Rivera murals at the DIA from later being destroyed as they were in Chicago because of his demonstrated communist leanings. Millions of Detroiters came to see what the fuss was all about and the DIA recorded it’s greatest attendance to that date, thus popularzing it’s future.

Artistically the murals are real wonders as the task of a painter to create such gigantic works was a profound and historic effort. The organization of the subjects and the color choices reflect the tasks in the Rouge and all is beautifully coordinated from piece to piece. Aesthetically they are consistant in character and present a continuous vision from smelting to manufacturing just as the process does, even today in the automotive industry around the world. Large murals present unique challenges to the creating artists that involve scale and proportion that are never truly visible until the work is in place to be viewed. Those special judgements and skills have been developed successfully by very few artists throughout history, all creative giants, like Diego Rivera.

Rivera very successfully turned to process to create them, as Henry Ford also did to build the products at the Rouge, the result being it’s huge size. Hopefully the Rivera mural development story that is retained by the DIA will be told some day as it will be very interesting to all who appreciate art of that scale offering I am sure much to learn.

Also of note is the fact that the DIA is currently getting ready to display a retrospective of design by the historic Detroit big three , a show that will highlight the best of design through their times.

The historic Automotive Industry mural in the tower of the Automotive Hall of Fame in Dearborn Mi, should also be noted. It was done by John, (Jack) Gable, a former and very talented General Motors designer who has developed a very successful career as a painter.

DICK RUZZIN

Editor’s Note: Dick Ruzzin is a well known GM designer nd car collector. He bought GM’s Mangusta, the only one built at DeTomaso with a Chevy engine.

Dick Ruzzin’s commentary on a par with the actual artwork and obviously well schooled in industrial history and auto art pieces given his rare Mangusta patronage.

Thank you for the article and the comments.

I am a great admirer of Diego Rivera, having seen his work in Mexico City. However pride of place in my poster collection of Grand Prix posters is the one that was made for the Detroit Grand Prix VIII, June of 1989. It uses the motifs from the mural with the production line and the workers in the caps and clothes pushing a yellow IndyCar down the line. It is quite simply the perfect poster for a race in Detroit, and a marriage of great arts and symbolism.