By Dick Ruzzin

In the 1990s I was Director of Design for General Motors of Europe, involved with all design work for GM, exclusive of North America. We had a design contract with Stile Bertone in Turin Italy and did many interesting advanced design projects there, most never revealed to the public. Included was the OPEL MAXX that was a big influence on the Swatch car.

Designers from Opel Design in Germany would spend time in Italy working with the Italians at Stile Bertone. It would be a gross understatement to say that an assignment at Stile Bertone was highly desirable by my designers.

I would visit Stile Bertone about once a month to review progress on our projects. One day in 1994, upon entering the lobby I was surprised to see a number of small colored sculptures on pedestals. Luciano D’Ambrosio explained that the models represented a very interesting project on which they were working. They wondered if I, representing GM Europe, could help. Little did I know how this new project reflected upon one of Bertone’s most famous and controversial designs.

D’Ambrosio then explained that Stile Bertone had sponsored an engineering student intern from an Italian university who had an amazing electric car project concept – to build a high speed record car that would average a 200MPH speed for 24 hours!

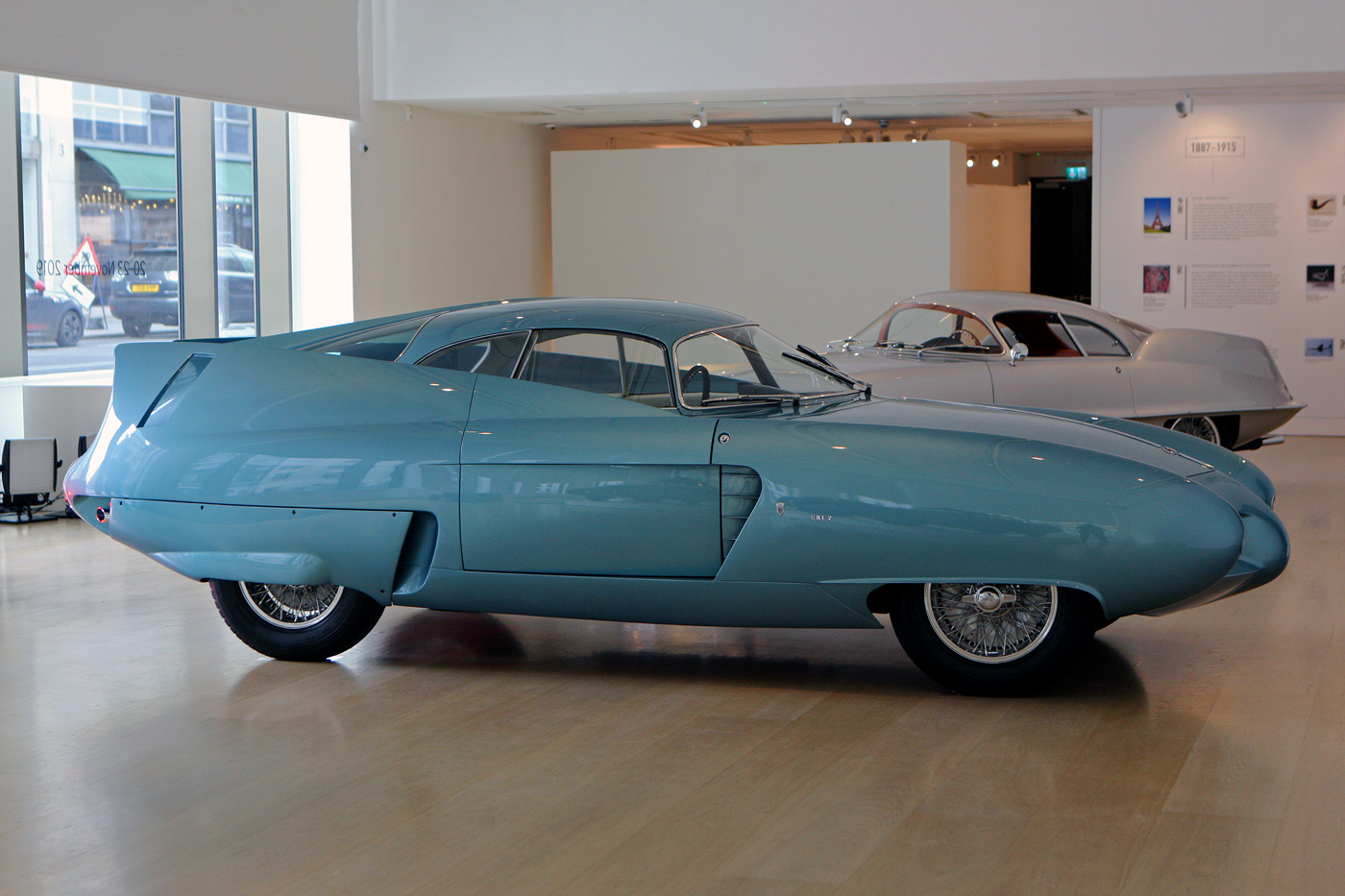

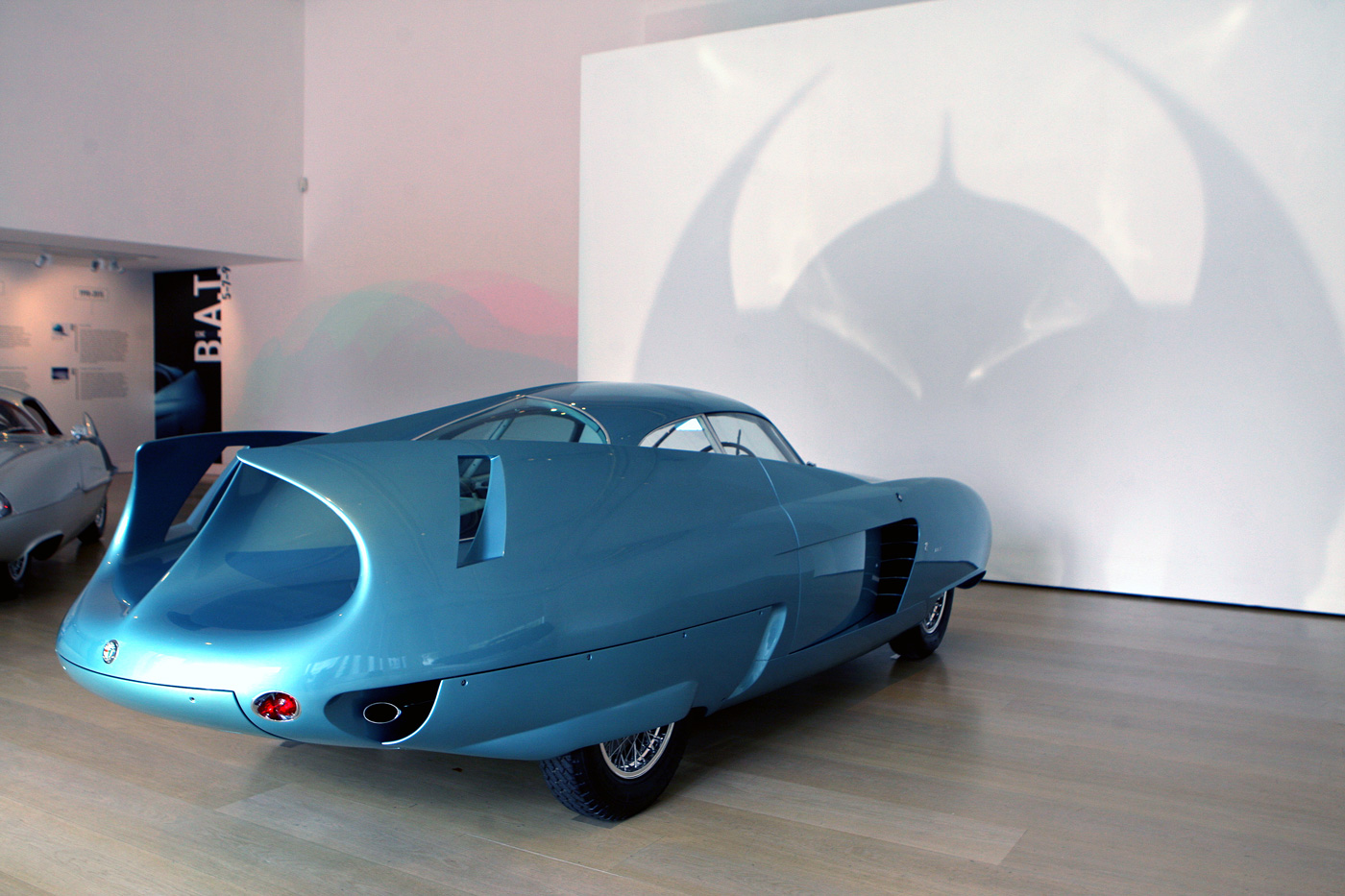

The construction of the car was well under way and Stile Bertone was seeking support in the form of funding. Named the Z.E.R. (Zero Emission Record), it was a very interesting concept, and would have significantly lower drag than the famous Scaglione B.A.T. cars which did so much to enhance the Bertone brand. Nuccio Bertone, then 80 years old, was still interested in environmentally friendly vehicles and had a hand in the 1992 Blitz, an electric sports car. and was very enthusiastic about the project.

I knew immediately that to get a large sponsorship on such short notice was impossible, but I kept that to myself in respect for Stile Bertone and agreed to present the idea to my supervisor at the GM Europe Technical Development Center. To better show the concept I asked for one of the models, so that I could have the Opel DTM racing graphics applied to the model before presentation to the GME management. Funding was refused but that didn’t stop Bertone.

Without our participation Stile Bertone was still able to fund the project and run the car as they were very passionate about it. They did not reach 200MPH for 24 hours but eventually, the car broke the 300 km/h mark and topping out at 303.977 km/h (188.88 mph) and set a world speed record for electric cars. I was told that the drag coefficient number for this car was 0.11, significantly lower in drag than the B.A.T. project, the best of which was B.A.T. 7 with a drag coefficient of 0.19.

Comparisons between the 1954 B.A.T. project and the 1994 Z.E.R. are difficult. The Bertone E car being electric also has some real advantages that lower its drag. Not having a radiator opening is a big plus on this kind of car and the frontal area compared to the overall length is also a big factor. Since the Z.E.R. has a very large turning circle the completely covered wheels also help, as well as the taper in the rear body plan view and the very idealistic smooth and round front end shape.

The biggest advantage however, is the fact that the Scaglione Alfas were very well developed with very little aerodynamic knowledge or tools, compared to what was available by 1995. We quote from Bertone in a Telex to Strother Macminn:

The B.A.T. 5 model was made directly in full size with very few sketches and most of the work directly done at the modelling stage by Franco Scaglione and continuously reviewed by Nuccio Bertone himself. At that time, no wind tunnel tests were executed. In order to get some aerodynamic information, we used the system of fitting on the outside body some wool threads. The cars were then driven on the road at different speeds and the pictures showed the aerodynamic movements of the wool threads.

On other hand, forty years later, the initial shape of the Bertone Z.E.R. would have been developed based on existing knowledge even before entering the windtunnel. It would have then been carefully created based on known and tested data. Then would come the hard work, the test by test refinement that would surgically shave drag points off of the car in the windtunnel.

Generally thought to be Scaglione’s most dramatic interpretation of the B.A.T. theme. For the second go around the engine was set back and lowered the hood line 2.5 inches at the nose. Photo by Jonathan Sharp.

*Thanks to the book, “The Bertone Collection” by Gautam Sen and Michael Robinson, Dalton Watson, 2018.

Very interesting story, Dick.

Roy

Great article Dick. I was always impressed with the ALFA Bat cars and how aero efficient they were without all the modern tools like Computational Fluid Dynamics. Amazing what a bunch of strings taped on a car can tell an engineer!

Bob Berta

Thank you Roy.

Dick Ruzzin

Bob,

The tufts of wool really work but when you see pictures of them no-one ever talks about what they are saying. If you do it enough you start to learn the language, how they wiggle rapidly under positive pressure and how they just lay there wobbling or standing straignt up under negative pressure. It takes a lot of tests to start to understand what is happening but you can also practice by watching cars when rain is just starting to fall and puddling on a cars surfaces. You are driving near them, of course.

On the freeway pull alongside a tractor trailer, a little closer than normal and slowly drive up toward the front of the truck. When you get to the cab’s front door slow to the speed of the truck. Focus on what is happening to the car, you will feel the shock wave coming off the front of the truck, the lighter your car is the more you will feel the body of your car wandering on it’s suspension.

If you pay attention while you are driving, especially in a light car, you will feel the aerodynamic forces at work.

Dick Ruzzin

Another nice read Dick, keep up the good work! Can’t wait for the next one.

Thank you Daniel, Have a great Christmas and stay safe.

Dick Ruzzin

Great project, beautiful solution! Simple efficiency.

However, how could an electric vehicle circle nonstop for 24 hours without “refuelling”?

And if a very large turning circle was chosen, I suppose the car would always turn in the same direction. Then why not adopt an assimetric shape ?

Kohler,

The vehicle had a battery casette that could be changed quickly while drivers were also changed at the same time, I assume.

Regarding symmetry, I have no experience in that scenario but the circle travelled was very large, probably scrubbing off a little speed, 2 or 3 Ks. That allowed the covered wheels. That being the case if there was any aerodynamic advantage to being assymetrical I am sure they would have done it. Maybe it is but I think the actual shape difference would be so small as not to be visible onthe models.

My only experience in documented “speed scrub off” was a one time ride in my 1995 Opel Calibra four wheel drive turbo coupe, lowered and also with a performance chip around the GM Europe test track in Dudenhofen, Germany. The driver was the Director of Advanced Engineering who had also been the Director of the Opel DTM Racing program. On that ride the car achieved a clocked speed of 270KPH. I was told that actual speed on a straight Autobahn would have been 275. They had measured the scrub off for high speed tests. Engineers do that kind of thing.

Dick Ruzzin