From Birdcage to Supercage

By Willem Oosthoek

Dalton Watson Fine Books, 2004

Hardbound, 338 pages

ISBN 185443-205-2

Want a chance to win this book, valued at $140 with FREE worldwide shipping? Be a Premium Subscriber and email me at vack@cox.net.

Review by Pete Vack

All images courtesy the Author and Publisher

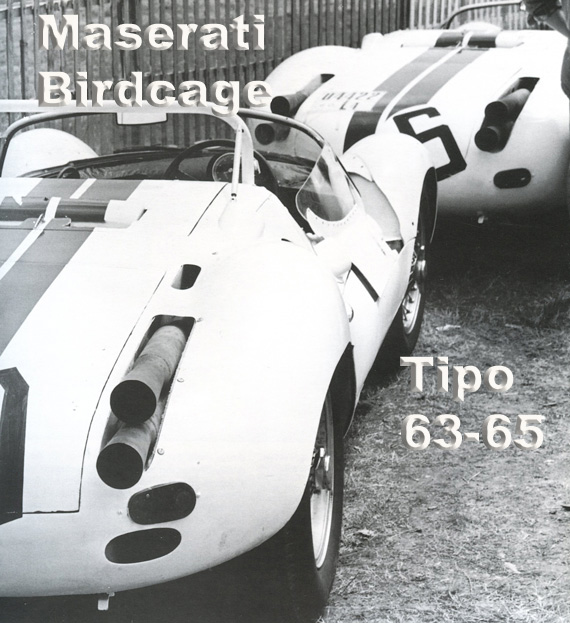

“From Birdcage To Supercage” covers the rear engined Tipo 63-64-65 Maseratis while “Magnificent Front-Engine Birdcages” covers the front engined Tipo 60 and 61s. The two volumes are available in a special slipcase and if ordered together cost only $225 – a savings of $65.

“From Birdcage To Supercage” covers the rear engined Tipo 63-64-65 Maseratis while “Magnificent Front-Engine Birdcages” covers the front engined Tipo 60 and 61s. The two volumes are available in a special slipcase and if ordered together cost only $225 – a savings of $65.

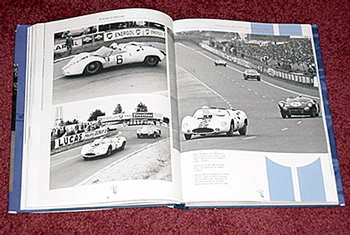

“From Birdcage to Supercage” literally bursts from the pages, casting its considerable content upon the widened eyes of the beholder. The 10 x 13 inch portrait format is huge, and the 350 superb photos are not only enlarged to the maximum extent possible, but most have not been seen in print.

But don’t think of this as a coffee table book, which is generally slang for a potboiler bought at Books-A-Million by a well-meaning relative as a Christmas gift. Willem Oosthoek’s 338 page opus is a serious, in-depth history of the ten little known rear-engined Maseratis which were built from 1961 to 1965.

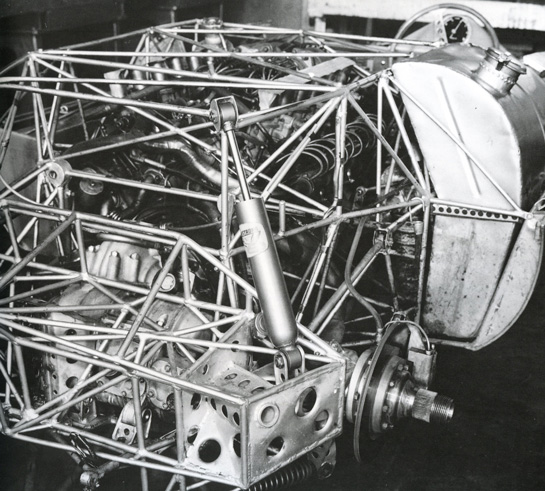

For one brief and perhaps not so shining moment, the Tipo 63, 64, and 65 Maseratis, in both four-cylinder, V-8 and V-12 form, blasted onto the racing scene, creating a great deal of power, noise, and controversy. They featured the most complex chassis ever known to man or machine. That they were known as the “Supercages” was not surprising, as the increased number of tiny tubes needed to support the larger, more potent car made the earlier Tipo 60 and 61 Birdcages look like Tweedy Bird’s old home. It was Maserati’s swansong, the last competition car made by the factory under the Orsis.

Fierce, fascinating, formidable, the rear-engined “Cages” were ignored by the factory, collectors and historians until the early 1990s, when Oostheok, Egon Hofer and others started tracking convoluted history of each car.

The photography and layout deserves special mention. First, there are few photos less than eight inches in width, and a good percentage of the black and white selections are given a full page or larger, treatment. Second, the source, quality, and reproduction, is excellent. According to Oosthoek, “The main body of photos came from three people: Bob Tronolone, Flip Schulke, and Egon Hofer, who had excellent archives with negatives taken by Pete Coltrin. Bernard Cahier came to the rescue for the Nurburgring, and Geoffrey Goddard and my late friend Henri Beroul for Le Mans. Bill Green helped me with Watkins Glen. The Bridgehampton photos came from the Ludvigsen Collection in London and European friends like Michel Bollee, Walter Baumer and Andre Pibarot.” A magnificent cast. The photos and the generous treatment allowed by Dalton Watson are worth the price of admission.

Thankfully assuming a great deal of knowledge on the part of the reader, Oosthoek wastes no time in getting very deeply into the subject, focusing on the rear engined cars, providing only a brief background on the front engined Tipo 60 and 61. For those who are expecting a history of the original Birdcage, look elsewhere.

Thankfully assuming a great deal of knowledge on the part of the reader, Oosthoek wastes no time in getting very deeply into the subject, focusing on the rear engined cars, providing only a brief background on the front engined Tipo 60 and 61. For those who are expecting a history of the original Birdcage, look elsewhere.

Oosthoek chose to organize the material by race rather than individual serial number — which makes sense from a chronological perspective but detracts from the emphasis of the Maseratis. Perhaps this was intentional; for Oosthoek brings forth the entire era, describing the competitors such as Porsche, Ferrari, Scarab, and Chaparral in detail. There is much more here than Maseratis. The rear-engined Maseratis participated in 17 events from 1961 to 1965, and there is a chapter on each event, with complete results and grid positions. Fortunately for us, the Supercages participated in FIA WSCC events, SCCA, the Professional West Coast series, and the Nassau Speedweeks. Oosthoek not only details the fate (and the state) of each Supercage in the particular race, but recounts each race from an overall perspective.

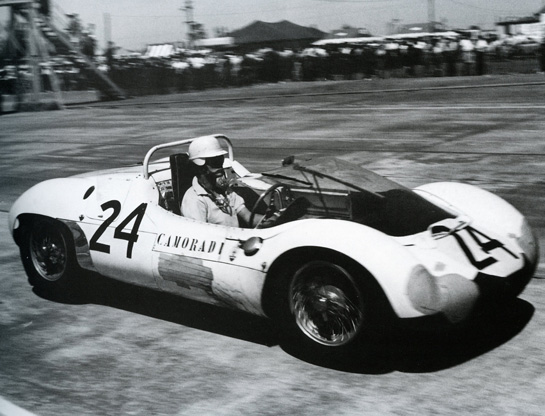

Sebring 1961 was the first test of the rear engined Cage. In this Flip Schulke photo, Masten Gregory waits in the Camoradi entry.

Inserted between the race descriptions are chapters relating to the development of the cars. For example, “Banking on the V12” describes the manner in which the potent 3 liter 310 hp engine replaced the aging four cylinder unit, while chapter 11 discusses the redesign after the 1961 Le Mans event. Thus chronological continuity is maintained throughout, while providing detailed insight regarding the development of the model. It is an unusual structure, but works.

SUPPORT VELOCETODAY BY BECOMING A PREMIUM SUBSCRIBER

Maserati’s racing efforts in the 1960s were supported entirely by independent teams, which makes the story even more complex and interesting. Oosthoek devotes a chapter to those teams, including Cunningham, Scuderia Serenissima, Camoradi and a separate chapter on the Tipo 65 and Colonel Johnny Simone—who has remained a mystery since his untimely death in 1967.

Maserati-T64 chassis from the rear, January 1962 equipped with the V12. Supercage was a fitting description.

Oosthoek pays particular attention to the background. Explaining the successes of the Tipo 61 during the 1960 SCCA season, he notes that the appearance of the Lotus 19 in the hands of Moss and Gurney late in the season, gave notice to Maserati that the days of the front-engined car were over. It was expected that the Italian firm would create a rear-engined car to compete with the likes of the Lotus and Cooper Monaco’s. The simultaneous success of the Maserati 3500 GT in the US made it clear to the Orsis that they should continue to provide independents with competitive cars to race in the US. What wins on Sunday, sells on Monday—

Another Schulke image of the four cylinder T 63 at Sebring. It retired with rear suspension problems.

In the same fashion, he relates the changes which took place in the US, making sports car racing more exciting, and perhaps more popular than in Europe. USAC had created a professional series, the Cal Club continued on its own path, and even the stalwarts at the SCCA saw the need for a professional series of races. Fed up with the high cost and lack of reliability of Italian and British engines, race car owners soon began using the new generation of lightweight American V8 engines, shoehorning them into whatever chassis happened to be lying around the shop. American sports car racing came alive, and would eventually give birth to the Can Am series. But the days of the Ferrari and Maserati victories were not over yet, and added to the spectacle of brawn vs brains.

In addition to providing complete race analysis, Oosthoek has traced the history of each Supercage to date, sorting out the mysteries of serial number changes and false claims. The history of the seven Tipo 63s and two Tipo 64 cars are featured in a final chapter, followed by the race record of each car.

At Road America in September 1961, the Tipo 63 came through for the Hansgen/Pabst T63. This LWB T63, driven by Thompson, Kimberly and Cunningham finished 9th.

Oosthoek has provided a fascinating, in-depth look into a part of Italian and American racing history long ignored, and thoroughly documented the last of the red hot Maseratis. Dalton Watson has published a huge book. We should be very glad that historians like Oosthoek long to write and publishers like Glyn Morris at Dalton Watson are still willing to produce. “Birdcage to Supercage” is highly recommended and a must have for any serious Maserati or Italian racing enthusiast.

Read the in-depth review of the “Magnificent Front Engined Birdcages” Tipo 60 and 61.

Hamilton Vose had a rear-engine Birdcage with a Ford in it at the Daytona 2000km ub ’65. It broke early. He welded up the Panhard rod on our Lancia Flaminia Zagato–gas welding a few inches from the fuel tank. The weld is good to this day.

Pete,

We all have our own special memories from yester year… Flip Schulke accounts for at least a half dozen for me. When we bumped into one and other it was like “an old home week”, unending mattering.

Flip as a photographer was top notch, sadly one of those FL hurricanes did away with the bulk of his archive; dying at such young as deprived all of his vision. He’s always been one of my favorite “shutter clickers.”

Thanks for crediting him with those photographs!

Ciao for now,

Tom