By Jackie Jouret

Photo courtesy The BMW Archive

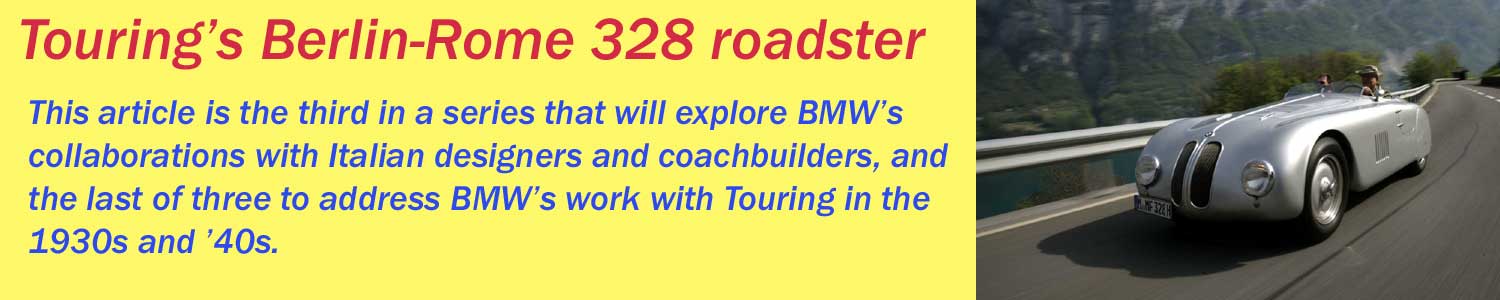

Among the most fascinating races of the pre-war era is one that never took place: the Berlin-Rome race. Announced in June 1937 for the following year, the race had been conceived by Adolf Hühnlein, an early follower of Adolf Hitler, who in 1931 became head of Germany’s National Socialist Driver Corps (or NSKK, to use its German acronym). The NSKK was in charge of all motoring and motorsport activities for the Nazi government, and Hühnlein ensured that German racing was well-supported in service of its propaganda value. A high-speed race on the newly-built freeways connecting the two Axis capitals would be ideally suited to that purpose, and it would allow German and Italian automakers to highlight their technical superiority where aerodynamics were concerned.