By Jackie Jouret

Photos courtesy The BMW Archive

As we saw in the first three installments of this series, BMW had fostered an association with Touring of Milan before World War II put an end to civilian automotive activities in 1941. That association had resulted in the Superleggera coupe that won the 1940 Mille Miglia, a pair of roadsters for which Touring crafted the bodywork to a design by BMW’s Wilhelm Meyerhuber, and a trio of stunning roadsters created for the proposed Berlin-Rome race.

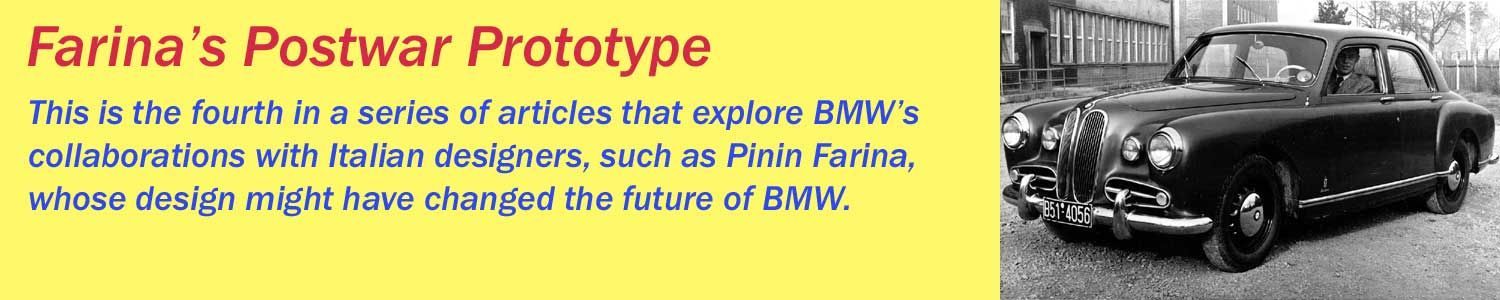

One might have expected the Touring-BMW partnership to have resumed after the war, given the competitive and aesthetic success of those automobiles, but it did not. When BMW began building cars again in 1951, the company turned instead to Pinin Farina for the external proposal that would be weighed against an in-house design for the 501 sedan.