By Jackie Jouret

Photos courtesy The BMW Archive

When it emerged from the destruction of World War II, BMW got back into business, first with motorcycles (in 1948), and then with high-end automobiles (in 1951). That was a logical strategy given BMW’s particular circumstances, but it began to fail by the mid-1950s. Even as the German economy was improving, BMW’s full-size sedans remained too expensive for most buyers. Worse, the motorcycle market was tanking, as riders abandoned two-wheelers in favor of motorcycle-engined microcars, which kept their occupants dry and warm regardless of the weather.

Desperately in need of a mass-market automobile, BMW licensed production of the two-seat Isetta microcar from the ISO company of Bresso, Italy, which had introduced it at the Turin Motor Show in November 1953. A few months later, it was shown at Geneva, where it was seen by BMW executive Eberhard Wolff. Wolff saw ISO’s egg-shaped microcar as the perfect bookend to BMW’s large sedans, and he raced back to Munich to finalize an agreement for production of the car at BMW. ISO was only too happy to provide the tooling, etc., and the company even permitted BMW to improve the car however it saw fit.

BMW’s version—known internally as the Type 100—was launched in April 1955, a little over a year after Wolff saw it in Geneva. In the interim, BMW had swapped ISO’s two-stroke engine for one of its own motorcycle engines, a four-stroke single that displaced 245cc and put out 12 horsepower. Nearly everything else had been replaced, too, from the mechanicals to the sheet metal; apparently, no parts are interchangeable between an ISO Isetta and a BMW Isetta.

Did Giovanni Michelotti provide a design consultation on the Isetta, either at ISO or at BMW? It’s possible, but no evidence has been presented to back up that claim.

The exterior design follows the basic Isetta outline, but it’s more refined in terms of its details, and it appears to have been better-built as well. As to who was responsible for these improvements to the original design by Ermenegildo Preti and Pierluigi Raggi, that’s never been disclosed by BMW. In their definitive design biography, Giovanni Michelotti: A free stylist, authors Edgardo Michelotti and Giancarlo Cavallini state that Michelotti had consulted for ISO on the design of the Isetta. The book doesn’t provide drawings to back up that claim, and the BMW Design Archive doesn’t include any Isetta drawings with Michelotti’s signature even among those that depict the Export and other variants created in 1957. It’s certainly possible that Michelotti consulted on those, however, as he had been working with the Munich carmaker since 1953—via his drafting of the 505 Diplomat sedan built by Ghia-Aigle for BMW—and took on an official role as consulting designer from June 1957.

A free stylist makes no claim whatsoever for Michelotti’s work on a four-seat version of the Isetta, the Type 102 that would be known as the 600 after it launched in 1957. Despite that omission, we can be relatively certain that Michelotti had a hand in this car’s design thanks to a drawing within the BMW Archive.

[Note: The BMW Corporate Archive is the general repository for BMW documents of all types, and as such it contains some design drawings. More drawings are contained within the BMW Design Archive, a separate archive created and is maintained by BMW Group designer David Carp. I’ll refer to both archives throughout this series, and I’ll quote Carp where his research proved determinative.]

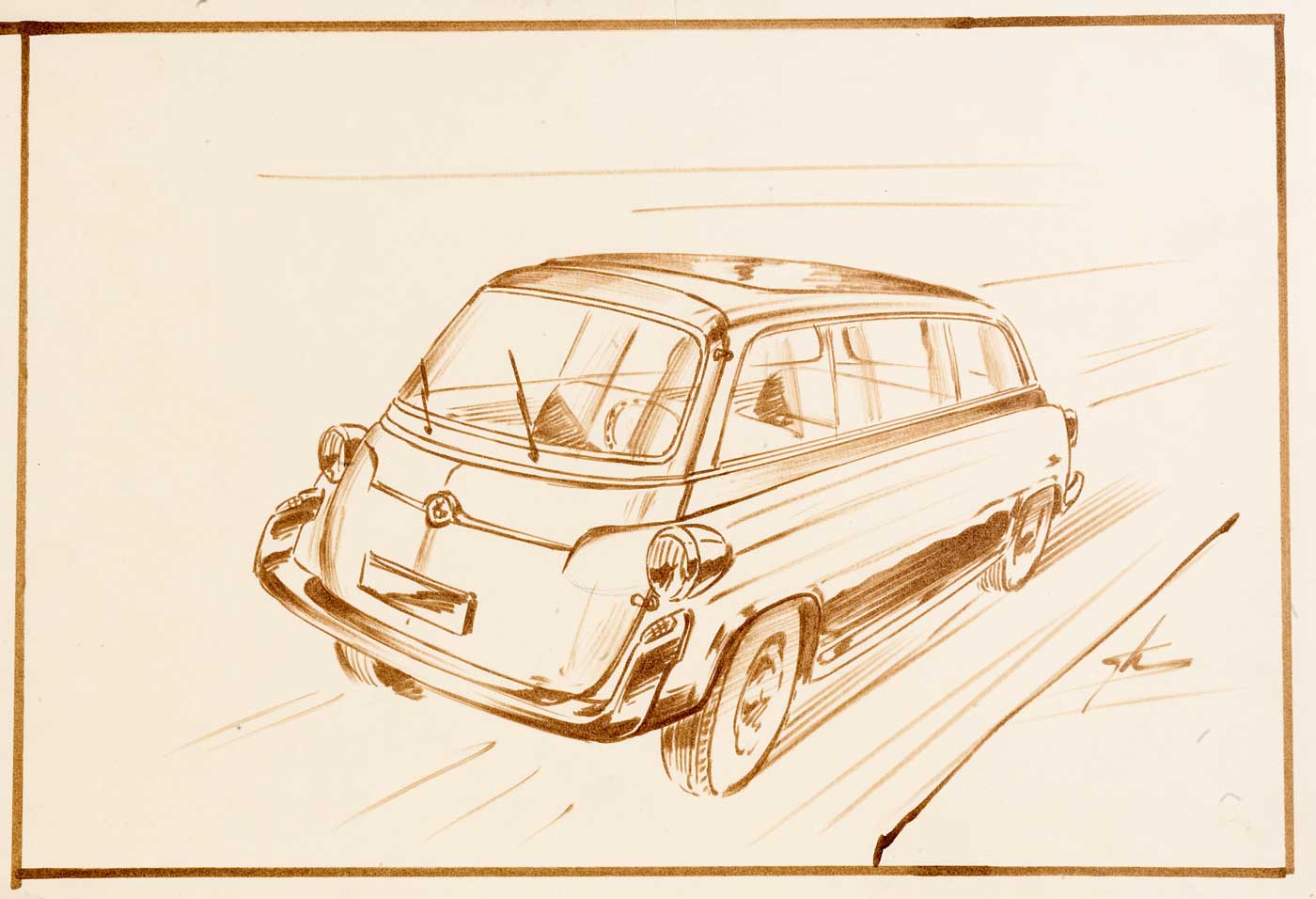

When BMW decided to expand the Isetta with a second row of seats and a more powerful engine, Michelotti sketched a proposal for a redesign of the car’s front section.

The 600 had four seats instead of two, with a second door for rear-seat passengers on its side as well as the front-opening door that it shared with the Isetta. It also had a motorcycle-derived 582cc two-cylinder engine with 19.5 horsepower, and an all-new semi-trailing arm rear suspension that would remain in use by BMW until 2003.

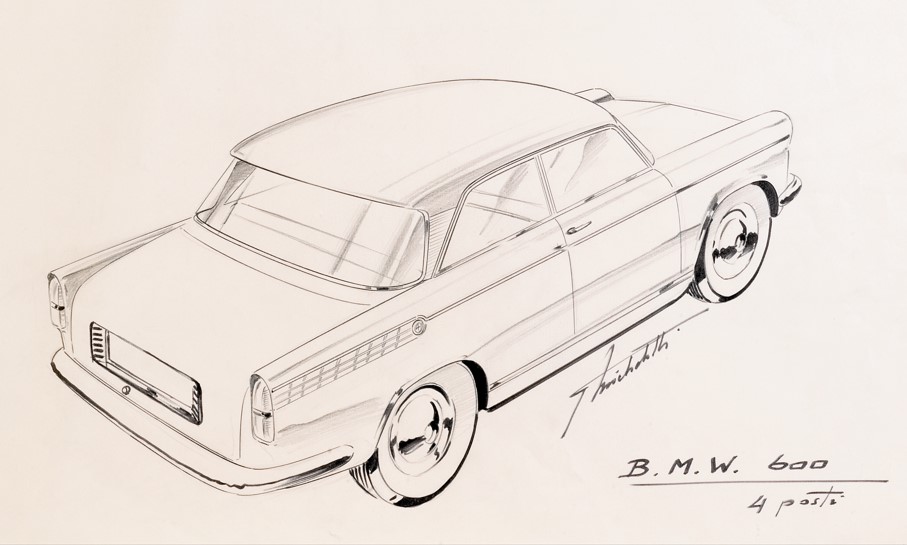

The 600’s design is interesting, though it’s rarely discussed and has never been formally attributed to any particular designer. According to Carp, work on the Type 102 started in 1956. “We have two original renderings by [Albrecht Graf von] Goertz, who was still on board at BMW at that time, and some by Erich Palm, as well as the painted bodyshell of a small scale model of his design.” (The German-born American designer Goertz, as many of you will be aware, penned the 503 coupe/convertible and 507 roadster for BMW, both of which are recognized as classics of their era.)

The BMW Archive also contains a sketch by Michelotti that shows the car from the front three-quarter view, and which looks very much like the 600 as built. Carp thinks that Michelotti was most likely responsible for the design, as early versions of the 600 look very much like what he sketched. The rear of the car, on the other hand, does not. “The more I compare the production rear end of the 600 with our archived drawings, the more I come to believe that Michelotti designed the front half and Palm/[Georg] Bertram designed the rear half.” Indeed, the Archive contains several sketches signed by Palm in which the car’s rear is depicted almost exactly as the 600 was built.

The 600 was not a success, not because it was a bad car, but because customers wanted both doors on the sides. The front door was a known liability within BMW even before the start of production in late December 1957, and it contributed to the car’s early demise in 1959. By then, BMW built just 35,000 examples, far fewer than it had hoped to sell.

As produced, the 600—which retained the Isetta’s front-opening driver’s door—looked very much like Michelotti’s sketch.

Even before the 600 production line got rolling, the BMW board was directing the company’s engineers to develop a more conventional small car, and to collaborate with an Italian designer on its styling. The resulting car would be called the 700, and its design is generally attributed to Michelotti.

Again, however, the evolution of this car was convoluted, mainly because BMW’s scant resources made it difficult for the company to develop new products without revision or interruption.

To understand that process, it’s helpful to consider BMW’s internal “Type” designations, which were assigned to a project that was approved for development as either a concept vehicle or a production model. We’ve already identified the Type 100 as the Isetta, and the Type 102 as the four-seat 600. In between was the Type 101, a rather cute little car that was sketched by Palm as a miniaturized 503, and which was intended to be powered by a water-cooled four-cylinder engine of either 700cc or 800cc; it remained unbuilt.

The Type 103 became an official project when BMW CEO Heinrich Richter-Brohm gave his approval to a proposal from BMW’s Austrian importer Wolfgang Denzel. A successful racer of motorcycles, automobiles, yachts, and skis, Denzel had already built his own sports cars using Volkswagen chassis and engines. In Vienna, he was using the 600 platform to create his own version of a small BMW, one that would be sporty and fun to drive while appealing to the masses.

For its third and final microcar, BMW allowed Austrian distributor Wolfgang Denzel to build his own prototype. Denzel hired Michelotti to design it, and the car met with a favorable response within BMW.

Denzel increased the twin-cylinder engine’s displacement from 582cc to 697cc and fitted a second carburetor to boost output from 19.5 to 30 horsepower. He lengthened the wheelbase from 66.9 inches to 83.5 inches, increased track widths from 48.0 inches front/45.7 inches rear to 50.0 inches front/47.2 inches rear, and upgraded the steering from spindle to rack-and-pinion.

Most important, perhaps, Denzel hired Giovanni Michelotti to design his car’s bodywork. Michelotti began work on the car in September 1957, and his design was finalized by January 1958. The bodywork was crafted in Turin by Vignale, which mated it to the prototype that was ready by early summer 1958.

Denzel called it the WD600, and that’s the car BMW executives saw when they arrived at a secret location on Lake Starnberg, south of Munich, in July 1958. The car impressed a majority of those present, but a few naysayers were reluctant to accept a car created in Vienna and Turin rather than Munich. (It should be noted that some of those naysayers were involved with a similar project being developed within BMW under the Type 104 designation. It too was built atop the 600 platform.)

Seen from the rear, the Denzel-Michelotti prototype displays prominent tail fins, which function as air inlets for the rear-mounted boxer twin engine.

In any case, the Michelotti-designed two-door WD600 was small but stylish, with a sporty aspect that was highlighted by large air scoops to cool the rear-mounted engine. A lack of rear seat space was mentioned, but the car could be built as a sedan as well as the jaunty coupe shown at Starnberg.

By October 1958, BMW had agreed to put a new small car into production, assigning it the internal designation of Type 107. (We’ll leave the Type 105 and 106 aside for purposes of our discussion.) As such, it represented a fusion of Denzel’s Type 103 project with the Type 104 developed in-house by BMW. At BMW’s request, both Denzel and Michelotti continued collaborating with the company on its development.

The Denzel prototype had a trellis frame, but this would be replaced with a load-bearing monocoque body, BMW’s first. The development of the monocoque was led by Fritz Fiedler within BMW, with considerable assistance from the Budd Company, an innovative manufacturer in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (Interestingly, Budd’s Berlin subsidiary had built the bodies for BMW’s very first automobiles in 1929, but that initial collaboration ended in 1932.)

As reported in A free stylist, “Vignale was commissioned to built ten prototypes, but it didn’t have the technical skills to design the chassis,” Michelotti and Cavallini wrote. “In the fall of 1958, close and continuous collaboration was necessary, coordinated by Denzel, between the engineers in Munich and Turin.”

Michelotti refined the coupe’s design with BMW head of body production Wilhelm Hofmeister, and he also worked on the sedan variant that would be produced alongside the coupe. “The coupe/cabrio is 100 percent Michelotti in my opinion,” Carp says, “but I think the 700 sedan shows evidence of the merger of Type 103 and 104, in that it has a percentage of Bertram mixed in.”

Once the third microcar was approved for production, Michelotti worked with BMW’s head of body production, Wilhelm Hofmeister, to meld elements of the Denzel prototype with those of another car designed in-house at BMW. This 1958 sketch shows that process; note that the car is labeled as a 600, as the larger engine displacement had yet to be finalized.

It’s interesting to see how Michelotti modified his design by comparing photos of the WD600 to those of the production 700. The prototype’s smooth sides and slim character line survived, but the front and rear were simplified drastically for production. The quartet of headlights was reduced to a pair, one on each fender, and the central section further lost the pointed nose that would have been harder to stamp than the smooth profile of the production car. At the rear, the dramatic air scoops were eliminated in favor of small tail fins that terminated in vertical taillights, and the engine cover became squarer.

Many if not all of those changes were made to simplify the bodywork for series production, but it’s hard to argue with the result even from the standpoint of style. Very few microcars still look cool by today’s standards, but the 700 holds up rather well, with a timeless elegance conferred by its elegant proportions and superb basic shape.

The coupe is the most stylish, of course, with balanced proportions and a not-too-low roofline that slopes nicely toward the “trunk,” which is actually the cover for the twin-cylinder engine located above the rear axle. The sedan is more sedate, and more practical—still a two-door, but with a taller, squarer roofline that increases headroom for the rear-seat passengers. (A convertible version of the 700 was offered from 1961, designed by Michelotti and built by Baur of Stuttgart with its hardtop replaced by a folding canvas top.)

The 700 coupe was an immediate hit when it was revealed in its final form in June 1959, providing BMW with a much-needed boost during its financial crisis that year.

The coupe was the first to be ready, and BMW was so enthusiastic about the car that the company couldn’t wait for September’s Frankfurt auto show to reveal it to the press. On June 9, 1959, BMW brought 100 automotive journalists to Feldafing, the town on Lake Starnberg where the 600 had been introduced in 1957. That it went over well can be discerned by the smiles on the faces of the assembled BMW executives shown in a photo of the car taken at the launch, and on those of the journalists inside it.

While they were undoubtedly taken with its styling, the journalists also appreciated the car’s performance. The monocoque chassis made the 700 considerably stiffer than it would have been with the 600’s trellis frame, and 66 pounds lighter. It sat lower to the ground by 2.4 inches, and it used the game-changing semi-trailing arm rear suspension that gave it exceptional handling.

Even though it was tiny, the 700 coupe was pitched at families, particularly those whose children were still small enough to ride in the back seat.

Like Denzel’s prototype, the 700 had an twin-cylinder engine with additional displacement, and its 697cc ensured that it still put out 30 horsepower even with a single Solex carburetor, here mated to a four-speed synchromesh transmission.

In 1960, BMW complemented the original 700 with a twin-carb 700 Sport with 40 horsepower, which helped the 700 earn its nickname as the “workingman’s Porsche.” Entire racing grids began filling with 700s, and the cars were entered not only by privateers but by well-known tuners like Willi Martini and even the BMW factory team. In 1960, prewar Grand Prix legend Hans Stuck Sr. raced a 700 Sport to his last hillclimb title.

BMW engine boss Alex von Falkenhausen (with wife Kitty in the passenger seat) races the 700 in a hillclimb in 1961.

The 700 was a success all-around, and BMW sold some 190,000 examples in sedan, coupe, and convertible body styles. What’s more, the 700 effectively saved BMW from bankruptcy in 1959, when the failure of its premium car strategy nearly saw it absorbed into Mercedes. It also ensured further collaboration between BMW and Giovanni Michelotti, though his contract came up for renewal each year nonetheless.

To address the issue of rear headroom, BMW enlisted Michelotti to design a “sedan” version of the 700 with a boxier, more upright roof over the rear seats.

In the next installments of this series, we’ll look at two of the cars Michelotti designed for BMW: one that remained a prototype, and the other that brought BMW firmly into the modern era.

Leave a Reply