By Clyde Berryman

The big day, September 9, came at last. It had a distinctly patriotic theme about it to commemorate the participants and their sacrifices during the war. A crowd of over 200,000 was on hand to watch.

The race director was Charles Faroux. Money raised by the races would go to the Campagne Nationale du Retour and other charitable organizations which sought to help resettle French families torn apart by the war. The curtain-raiser was a 36-lap event for 1500cc cars without compressors which started at two-thirty.

The Coupe Robert Benoist was named after one of France’s most eminent pre-war Grand Prix drivers, the unofficial 1927 World Champion who won every race worth winning that year at the wheel of his Delage. Less known is that Benoist was also a war-time French Resistance hero, recruited into a network of Special Operations Executives (SOE) by his English friend and erstwhile teammate William Grover-Williams (of “Williams” pseudonym fame). Sadly, both would pay the ultimate price in the service of their countries. “Williams” was arrested by the Gestapo on August 2, 1943, and executed. Benoist clandestinely slipped away to England for some special training and returned to France, becoming a key Resistance figure before being captured himself in June 1944. Deported to Buchenwald concentration camp, he was hung there on 12 September.

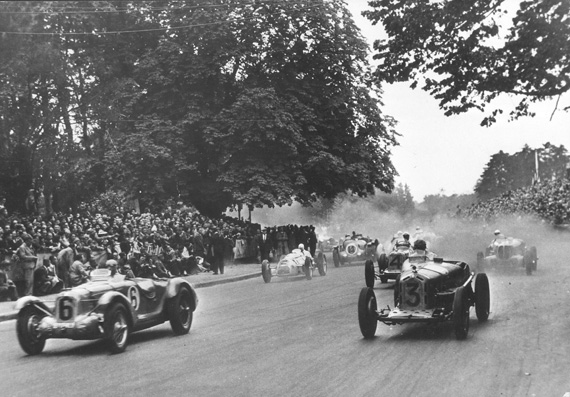

Start of the under 1500 race at the Bois de Boulogne on September 9, 1945. Photo courtesy Christian Huet, Roy P. Smith and Veloce Publishing.

The 1500cc race was overshadowed by the more important races which followed, but it saw a fairly effortless early-career win by car constructor Amedee Gordini at the wheel of the same Gordini T8 sports car which had won the “Indice de la Performance” award in the last pre-war 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1939. Robert Benoist’s widow was quite fittingly on hand at the finish to present the winner’s congratulations to Gordini.

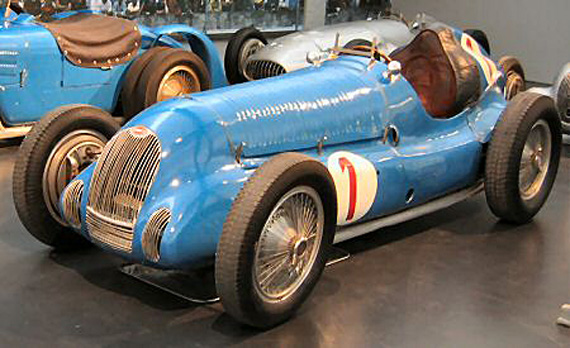

Gordini on the way to a class win at Le Mans in 1939. He would use the same car to win the very first Post-war race at the Bois de Boulogne. Courtesy Graham Gauld

The next race, also a 36-lap affair, was the Coupe de la Liberation for cars between 1500cc with compressors or 2000cc un-supercharged, which started a little over two hours later. In terms of sheer racing excitement, it was unfortunately on a par with the earlier Coupe Benoist. Henri Louveau, a hometown boy from nearby Suresnes who had been a bicycling champion in the 1930’s before turning to car racing, easily won in his Maserati 6CM. Auguste Veuillet came in second a full lap behind in an MG Magnette K3.

What was unusual about this race was the eclectic assortment of cars from vastly different eras which presented themselves at the start. Race organizer Maurice Mestivier was there himself in none other than an Amilcar C6 in which he would go on to finish fifth. In fact, there were no fewer than six Amilcars on the grid! Eugene Martin brought a Salmson; Rene Bonnet (of Deutsch-Bonnet fame) was there with a…DB (what else?), while Mancel Balsa had a Bugatti T39A. Other entries included an old BNC 527 and a 1750cc Alfa Romeo.

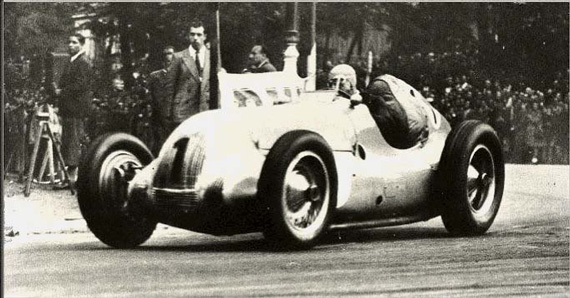

The grand finale was the Coupe des Prisonniers for all cars over 3000cc. As it turned out, this was the race that made it all worth waiting for. There was an element of drama before things even got underway as Jean-Pierre Wimille arrived too late for practice with his hybrid 4.7 liter Bugatti T59/50B. As a result, he was ordered by officials to start from the back of the grid. Already an established name in motor racing from well before the war, Wimille had raced Bugattis in the 1930’s with mixed success, winning second-tier races at Oran and Seichamps (Grand Prix de Lorraine) in 1932 and the Grand Prix d’Alger of 1934.

He denied himself almost certain success when he refused to consider racing for either Mercedes-Benz or Auto Union for political reasons. When war broke out, Jean-Pierre and his champion skier wife, Christiane de Fressange, were recruited into the French underground by Robert Benoist. Both had their share of hair-raising adventures and narrow escapes from the Gestapo, but they were more fortunate than Benoist in surviving the war.

After Paris was liberated, Wimille joined the Free French Air Force and flew with them for the remainder of the war. There is one story in circulation which might help explain his lateness to practice for the Coupe des Prisonniers: Since Jean-Pierre was still officially a soldier in uniform, he had been forced to apply for a special dispensation to leave his unit and travel to Paris for the race! His greatest rival for this event looked to be Raymond Sommer at the wheel of a new 4.5 liter Talbot-Lago T26. Sommer had perhaps an even greater reputation as a racing driver than Wimille at this point in their respective careers.

He had driven mostly Alfa-Romeo’s and Maserati’s in Grand Prix racing, winning at Miramas in 1932 and at Comminges and Montlhéry in 1935. He was a two-time winner of the 24 Hours of LeMans sports classic and ironically, had shared a Bugatti with Wimille to win the French Grand Prix at Montlhéry in 1936. And like Wimille, he too had fought in the French Resistance during the war.

The rest of the grid included former great “Phi Phi” Etancelin and future French talents such as Maurice Trintignant, who was racing the very same Bugatti T35C in which his older brother Louis had been killed in practice at Peronne, and Eugene Chaboud, the best of the seven Delahaye drivers at the start.

One of the latter, Louis Villeneuve, was reportedly so corpulent that he had no choice but to alter the sides of the Delahaye’s cockpit so he could fit in his seat! Just as colorful — and certainly more talented — was Louis Gerard in a Maserati 8CM. Gerard had a passion for beautiful cars which he could afford to indulge, as his wealth came from being an early “slot machine” magnate. He once bought a Delage on a whim and then with his friend Jacques de Valence as co-driver, proceeded to finish fourth at the 1937 24 Hours of Le Mans in his racing debut at age 38! He won the Ulster Tourist trophy in 1938 and would go on to live to the ripe old age of 101. However, this contest was going to be between Wimille and Sommer.

When the flag dropped at 17:45, Sommer not unexpectedly grabbed the lead, but Wimille was about to string together several of those sensational laps we have often come to describe as “lap of the Gods” during the early stages of the race. Charging from the back, he completed the first lap in fourth place. One lap later, he was lying in second. Sommer came roaring around the next lap with Wimille tucked-in firmly behind him.

On lap four, Wimille had found his way past into the lead on which he would proceed to build a comfortable safety cushion right to the finish. It was Jean-Pierre’s day without a doubt. He was absolutely untouchable. At the conclusion of forty-three laps and over an hour of racing, Eugene Chaboud trailed home in third place, three complete laps behind the furiously scrapping Wimille-Sommer duo.

Next: Part 3 looks at the last few races in the Park.

Dear Mr. Berryman: Congratulations on a well documented story on the restarting of racing in Paris. Just like Henri Louveau I have been a proud Suresnois for the last three years. Suresnes is just crossing the Seine, west of the Bois de Boulogne, and on those river banks a few car factories were established like Talbot – Darraq, Zebre and Cyclauto, and just south of there was the Usines Renault in Boulogne Billancourt. If you were to walk north from the Porte Dauphine hairpin, before the Porte Maillot rond point there is a small monument to mark the memory of the first car race in 1905 won by Emile Levassor driving a Panhard et Levassor car with a two-cylinder, 750-rpm, four-horsepower Daimler Phoenix engine over the finish line in the world’s first real automobile race. Levassor completed the 732-mile course, from Paris to Bordeaux and back in only 49 hours. I can send you a picture via e-mail. Congrats again

You are wrong about Sommer’s Talbot in 1945. It was not a “new T26” – they did not appear until 1948. It was the “monoplace centrale” of 1939, known as a T26 because it had the 26CV single cam hemi-head pushrod of which a handful of examples were built pre-war.