Alfa Romeo Tipo 33, The Development and Racing History by Peter Collins and Ed McDonough

2006, Veloce Publishing Limited, Dorchester, England,

ISBN 1-904788-71-8 $79.95 USD

By Pete Vack

A Brief History

The Alfa Romeo T33 was Alfa’s most successful post-war sports race car, yet perhaps the most frustrating for both Autodelta and Alfa race fans. Its ten year life spanned a huge variety of changes in race car technology, safety, and race track venues, and perhaps most significantly, dozens of rule changes deemed by the FIA.

It took eight years to win a World Championship for Makes, and by then no one cared.

The story, in fascinating detail and depth, has now been told by Peter Collins and Ed McDonough in their new book, ‘Alfa Romeo Tipo 33, The Development and Racing History.’ Despite the ups and downs, triumphs and tragedies, Alfa’s last shot at International Sports Car Racing was fun while it lasted. As veteran Alfa driver Arturo Mezario quipped “All races at Alfa Romoe were good, even when they weren’t!”

Born of Satta and Giuseppe Busso the 1967 T33 was so named due to the chassis designation Tipo 105.33…typical for Alfa at the time. What started out as a 2 liter V-8 prototype based on the OSI Scarabeo, (an interesting fact detailed by the book’s authors) the T33 eventually developed into a full monocoque flat twelve 3 liter, and, at the very end, a 2.1 turbocharged flat twelve, never fully sorted out before the suits at Alfa pulled the plug. In fact what is commonly referred to as the Alfa Tipo 33 is actually a multitude of cars developed by Autodelta, Alfa’s racing arm under the enigmatic Carlo Chiti.

The first, the T33, featured a ladder type H frame, with large parallel cross section tubes and a two liter DOHC V8 good for about 270 hp. The T33/2 had a different body and side radiators, and was raced with both the 1995cc V8 and a 2462cc version.

In addition to AutoDelta’s team, there were private entries such as this T33/2, driven here by Richard Pilkington at Brands Hatch in 1976. The same car had won that same event five years before, in 1971!

By late 1969, Chiti discarded the troublesome H frame and designed a monocoque chassis, while the engine was upgraded to a full 3 liters with 400 hp on tap. This was called the T33/3. Although introduced at the 1971 Targa Florio, the T33 TT3 was campaigned actively in 1972. TT meant Telaio Tubolare. Yes, from a monocoque chassis to a space frame. Progress, Chiti style.

In time the V8 had run its course, and for 1973 a new 3 liter flat twelve powered the still space framed T33, the designation being T33/TT/12. This model won the World Championship of Makes in 1975. The last, and most successful 33 variant was the T33/SC/12. The SC meant Scatolato, roughly translated as monocoque, which again won the World Sportscar Championship in 1977.

Carlo Chiti

Autodelta was Carlo Chiti and the T33, despite having roots at Alfa (including the V8, which had first been created in the mid 1950s by Satta’s team), was Autodelta. Chiti’s role in the T33 story is pivotal, dominant, and even in 1975, when the team was largely financed and run by Willi Kauhsen, Carlo Chiti never let loose of the reins. Chiti had his finger in every pie, but like most mortals, did not have enough digits on his hands or feet to control everything effectively.

The authors give Chiti his due, and for the most part, everyone recalled the domineering Autodelta chief with fondness, even kindness. Only John Surtees offered a totally different, negative-but-honest perspective.

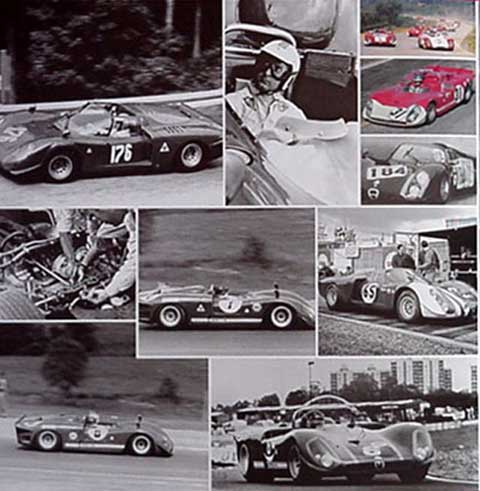

The authors compiled a great number of photos, and those which were not clear enough for reproducing in a larger format were gathered an presented in an appendix.

Chiti was a Tuscan, born in Pistola in 1924. Young and lean in his youth, he graduated from Pisa University in 1951 and joined Alfa Romeo in 1952. In later years, his love for food made him rather rotund, and he earned the nickname “Chitone”, a not-so-vague reference to the Michelin Man.

A warm, humane person whose office was always full of stray cats and dogs, Chiti also had some strange habits. Rather than assiduously track each chassis and keep comprehensive notes, Chiti’s love of astrology led him to name the various cars after astrological signs, a Nancy Reagan-like behaviour which fortunately did no last too long. Still, let the record speak for itself. The T33 participated in over 230 events in its ten year on the track, and won 62, most of which were non-championship (and therefore minor) events. Contrast this to the Ferrari 312P, created to win the sportscar championship in 1972 and did so immediately, winning 10 of 11 events in 1972, defeating the best efforts of the AutoDelta team in the process. Said Janos Wimpffen, Ferrari could do no wrong, Alfa could do no right.

Chiti was above all, like Ferrari, and engine man, often foregoing further chassis development. He solderied on with an ineffective and dangerous tubular H frame for almost four years before designing a monocoque chassis, only to cast it aside in favor of a space frame less than two years later! In the meantime, the engines went from strength to strength and overall, were extremely reliable. In the end, Chiti and his team got it all together and fielded an extremely potent, world class race car which totally dominated the 1977 season. Ironically, by then, there was little competition and the victories were gutless.

The Book

The authors have done a tremendous job tracking the long history of the cars and events, writing much in the fashion of Peter Hull and Roy Slater, who spent years putting together the landmark ‘Alfa Romeo, A History’ (Cassell & Co, 1964), organizing the work by year and race.

What makes the Collins/McDonough effort stand out is the fact that unlike Hull/Slater, they went to great lengths to find and interview almost every living driver who ever drove a T33–and the list is both impressive and long. Included are relevant and revealing comments from John Surtees, Vic Elford, Teddy Pilette, Arturo Merzario, Derek Bell, Jochen Mass, Giovanni Galli, Nino Vaccarella—and dozens of others. The inclusion of their remembrances makes this a very special book, and brings what could be boring racing history into vivid, colorful life.

The problem of chassis numbers and which cars participated in which events remains somewhat inconclusive. As with Ferraris, this poses questions for owners and potential buyers–Alfa T33s are worth anywhere from 200K to 400K USD–yet is is often impossible to ascertain if a particular car raced or placed in any particular event. According to co-author Ed McDonough, “We have some good sources but everything has to be cross-referenced with photos to give satisfactory answers. We believe there is a listing done by Chiti but we haven’t got our hands on it yet. We used a system which required three separate pieces of evidence for us to accept that a car did a certain race. Some of that came from Galli who noted his chassis numbers, and knew when he drove the same car. It is however a minefield and while interesting, tends to muddle the achievements of the cars themselves.

Ed McDonough hustles in a Tipo 33/2, one of the six T33s he reports on in a special chapter. Truly a guy who can write and drive at the same time!

Ed McDonough, that all around guy who drives as well as he writes, has taken on a huge task and done it well, ably assisted by Peter Collins No one else seemed up to the job, one which desperately needed doing, as information about the well known T33 is scarce and usually inaccurate. It is one of those absolutely essential books which will be referenced time and time again. In addition to the ten year racing history, McDonough gets into the cars themselves and offers a chapter on driving a variety of the T33s, plus additional chapters on the T33 Stradales and Concept cars. A lot of new, valuable, and interesting material is packed into this book.

Alfa Romeo Tipo 33, The Development and Racing History will be the main reference for the T33 for years to come, but the authors plan to follow it up with Volume 2, adding even more history to the Alfa race car, and more information on chassis numbers.