By Daniel Cabart and Claude Rouxel

Volumes I and II Part I of a two part review

Review by Pete Vack

All images courtesy of Dalton Watson

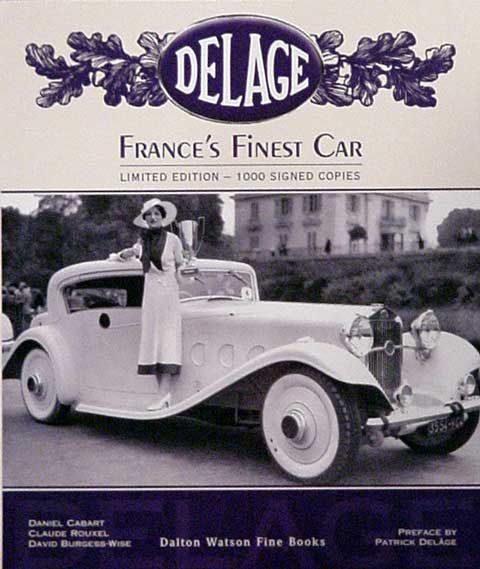

This comprehensive two volume set on Delage is more like a travelogue through history, a fascinating flow of people, posters, catalogues, sidebars, notes, statistics, art and marvelous photography all presented on the highest quality binding, paper and reproduction. In fact, it is almost like walking through a museum of winding passages, with lighted windows full of interesting artifacts and artful displays that superbly illustrate the subject.

The two volume Delage set makes full use of evocative photos, such as this family in their A or B Type Delage in 1906 or 1907. The only difference between the two types was the displacement of the one cylinder engine.

The two volume Delage set makes full use of evocative photos, such as this family in their A or B Type Delage in 1906 or 1907. The only difference between the two types was the displacement of the one cylinder engine.

Pages measure 290mm by 240mm; the text paper is 170 gsm Stora Enso Matt Art. This is a format that allows the space and quality for the presentation of some of the most beautiful car art of the early 20th century, as well as excellent reproduction of outstanding photographs from a wide variety of historical archives. Both volumes with dust jackets fit into a glossy cardboard case. The layout is large, bold and strongly visual that often screams “wait, read me!†or “Pssst! Want some additional facts and figures?†It is a formula that will cause distraction, pleasure, or a bit of both. This is not a criticism, for it is a joy to return to the book and discover something new along the way, a sidebar or photo overlooked.

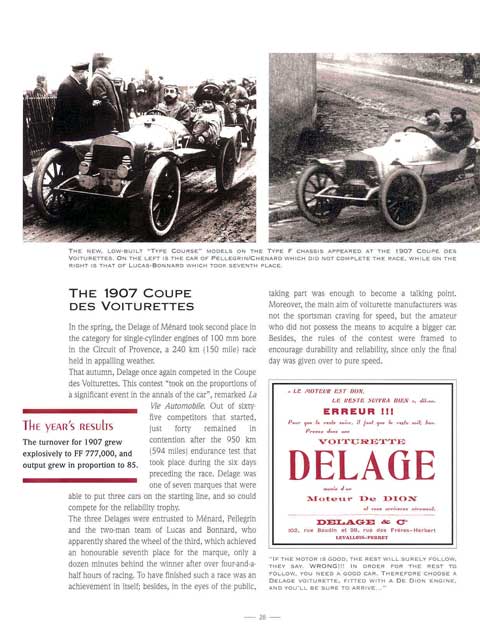

A typical page from Volume One–sidebars, statistics, photos, and text share the page, but pleasantly so.

The authors, Daniel Cabart and Claude Rouxel, may not be well known outside of France, but the English translation and additional text was accomplished by David Burgess-Wise, who has authored over 30 books and is also a Delage owner himself. David has ensured that the English text works smoothly and is easy to follow. Cabart and Rouxel have made use of the two main sources of information about Delage; the diaries of Delâge’s right hand man Augustin Legros, and the work of Paul Yvelin, who previously wrote and published a book about Delage in 1971. Since the publications of the French version corrections have been made and additional pages added to the English version. But as Louis Delâge’s grandson Patrick noted in the preface “a wider view should be taken†and that was achieved by Cabart and Rouxel who finished the Delage book in time for the 100th anniversary of the marque in 2005. Shortly after publication, the original French edition won the 2005 Prix Bellecour and a 2006 Society of Automotive Historians Award of Distinction. There is a bibliography and index, but no footnotes; however most sources are woven into the text.

(A note on the use of a circumflex accent marks over the “a†in Delâge; When referring to the man or family, the accent mark is used; when referring to the car or company, it is not.)

Although there are a few books on Delage, most are now out of print. “Delage: France’s Finest Car†is probably going to be the standard on the marque, at least in English. The chapters are in segments of 3-5 years, the first being 1905-1909, 1910-1914, etc. Volume One, at 373 pages, consists of a combined history of the car, the models, racing, financials, and a surprising amount of material dealing with the people who made Delage what it was. Volume Two is a 155 page compendium of Delage ads, posters and statistics which include all the specifications, numbers built, surviving cars, the Delage racing record, and a variety of Delage information which did not easily fit under the chronological constraints of Volume One, such as “Delage Down Under.â€

The Car

It is not our goal here to provide any kind of in-depth history of Delage; that is the purpose of the two volume set we describe. The following are just a few highlights of the fantastic cars from this distinguished French manufacturer. Part I will deal with the years up to 1920, in Part II we’ll briefly cover the 1920-1935 years, the difference between Delage and Delahaye, and why.

Delage, 1905-1920

Delage history began in 1874, when Pierre Louis Adolphe Delâge was born in Cognac, the son of a “watchman.†At the age of sixteen, young Delâge had been accepted into the Ecole de Arts & Metiers at Angers and graduated three years later with a degree in Engineering. By the time Delâge, who had taken to using the name Louis, was 35, he had founded an automobile assembly company.

Although not mentioned in the book, some have thought that the Delâge family was a bit more upper class than they liked to admit. According to Griff Borgeson (AQ 14-3), the family was able to afford to send young Louis to the Ecole, quite a feat for a mere watchman. Unfortunately, Delâge’s grandson Patrick does not provide any further details.

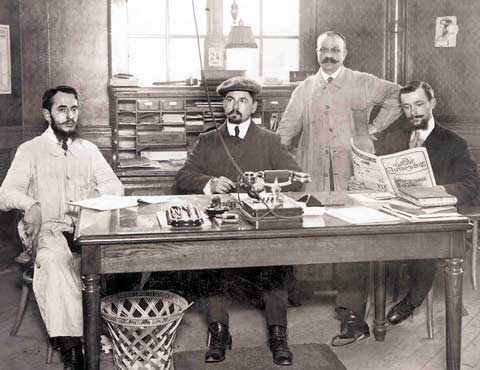

1910; the management team at Delage. From left, Ferdinand Demolliens, Augustin Legro, Schwob, and Michelat.

1910; the management team at Delage. From left, Ferdinand Demolliens, Augustin Legro, Schwob, and Michelat.

After finding a backer and establishing Delage as a company, Louis Delâge consistently found fresh engineering talent at the Ecole de Arts & Metiers, including Augustin Legros, Némorin Causan, Arthur Michelat, Albert Lory, and Charles Planchon. Delâge’s ability to attract and manage the top engineering minds of the day, much like that of Enzo Ferrari, was one of his greatest talents.

Starting in 1905 with a de Dion Bouton single cylinder engine, Delage production cars increased in size, engine capacity, and seating capacity, yet the quality desired by the founder continued to be a defining feature of even its light (voiturettes) cars. They were simple, but well built. Delage supplanted the little one and two cylinder de Dion Bouton engines with four cylinder engines made by Ballot and by 1912 began the design and production of an in-house 2.5 liter six cylinder. The workforce went from three to 552 in 1913, and the Parisian factory moved three times for expansions. By 1913 Delage was building and selling over 1300 cars per year. The models range consisted of small voiturettes to a long chassis limousine.

It was a heady time for Louis Delâge, the son of a watchman. But the best was just around the hairpin.

Racing 1905-1916

From the very beginning, Delâge had been interested in racing his products. A few cars had been entered in the Coupe de Voiturettes in 1906 and 1907, but in 1908, a special race car, the Type ZC, with an engine designed by Némorin Causan won the Coupe des Voiturettes at Dieppe. Delâge was elated but succumbed to pressure from his main supplier, de Dion, to claim that the winning car was actually powered by a de Dion engine. This bit of underhandedness understandably enraged the young and talented Causan, who left Delage in a huff.

Delage ads and posters are plentiful in both volumes. Here, the ad celebrates the victory of Michelat’s Type X at the Coupe de L’Auto des Voiturettes Legeres in 1911.

Delage ads and posters are plentiful in both volumes. Here, the ad celebrates the victory of Michelat’s Type X at the Coupe de L’Auto des Voiturettes Legeres in 1911.

But the victory and a growing profit margin encouraged the construction of another race car, the Type X. The designer who replaced Causan was Arthur Michelat, ex-Panhard Levassor, ex-Clèment Bayard, ex-Hermes, who came to Delage in 1910. Michelat was brilliant; his work for Delage would include twin ignition, four valves per cylinder, desmodromic valves and five speed transmission.

Michelat’s Type X race car was a three liter four with two plugs per cylinder, four horizontal valves per cylinder, lubrication via pressurized oil pump, and a Claudel constant level carburetor. It won the Grand Prix de Voiturettes Légères de Boulogne in 1911.

Michelat was just getting started. Along with Peugeot and Ballot, Delage would build the most advanced racing cars in the world and they would all be designed by Aruther Michelat.

Indianapolis

With the support of journalist W.F. Bradley, two Delages were shipped to the U.S. On May 30th 1914. René Thomas won the Indianapolis 500 at an average speed of 129.06 kph. Thomas was driving Michelat’s Type Y, which had previously won at the Grand Prix de France at Le Mans in 1913. The second Delage placed third. The winning car was bought by an American after the race, just as it was being loaded onto a ship bound to France. Later, it was found and restored by Edgar L. Roy, a great enthusiast who helped found the Vintage Sports Car Club of America. Today it is on display at the Indianapolis 500 Museum.

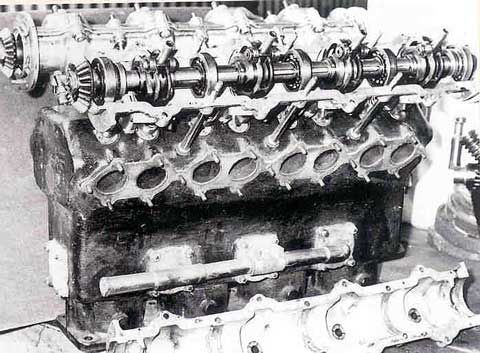

What appear to be camshaft bearing supports are actually the ‘cages’ used for the brilliant desmodromic valve operation on the Delage S.

What appear to be camshaft bearing supports are actually the ‘cages’ used for the brilliant desmodromic valve operation on the Delage S.

The Indy-winning four cylinder, horizontal sixteen valve, five-speed Type Y was ahead of its time, but the Michelat-designed Type S which followed combined all the very latest technologies to create what is considered by many to be the direct ancestor of all today’s cars. It boasted four wheel brakes (plus a transmission brake), the five speed transmission with dual overdrives and metal disc clutch from the Y, a new DOHC head design and the first successful racing application of a desmodromic valve operation.

One of the Type S Delages was entered at Indy in 1916. But the car was totally destroyed on the 61st lap of the event.

One of the Type S Delages was entered at Indy in 1916. But the car was totally destroyed on the 61st lap of the event.

Reportedly only four were built. The S failed to win the all important 1914 Grand Prix de l’ACF at Lyon–it was a Mercedes Benz walkover, a chilling foretaste of what was to come. The next month Europe was at war. Three or four, or perhaps five of the Type S GP cars were sent to the U.S., where in the hands of Barney Oldfield and others, they competed successfully in events from New York to San Diego until late 1916.

In 1986, Griff Borgeson received word that one of the Type S cars had survived two wars and the Depression in Australia. Not only had it survived, but it was in remarkably good condition and had been recently restored. The secrets of the Delage desmodromic valve operation soon came to light some 72 years after the car was first raced, and according to Borgeson, confirmed that the “priority of Michelat and Delage in the successful application of the desmodromic principles to the modern breed of high performance engines is unchallenged.â€

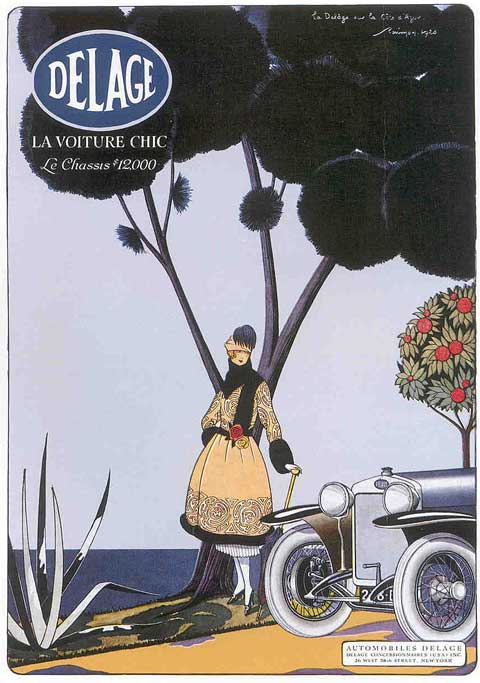

As this ad from the immediate post WWI era shows, Delage was ready for the roaring twenties.

As this ad from the immediate post WWI era shows, Delage was ready for the roaring twenties.

The guns of August 1914 changed everything. The Delage company would make munitions and some vehicles for the war effort. Louis Delâge, rich as the war started, became, at the end of the conflict, very rich. He was ready for the roaring twenties, and the day of the voiturettes would be over, at least for Delage.