Ford, Ferrari, and their Battle for Speed and Glory at Le Mans

By A.J. Baime

Houghton Mifflin , $26.00

ISBN-10: 0618822194

Hardcover; 320 pages, 20 photos

Review by Greg Vack

To be an American in the mid-1960s was to see the world as your oyster. We had the tallest buildings, the best highways, the strongest military, the smartest scientists, the biggest cars, the wealthiest people, and it was just going to keep getting better. Americans could achieve everything they set their minds on and anything else probably wasn’t worth doing anyhow. Go to the moon? Just give us a few years; we’ll be there. Conquer poverty? The president declared war on it and it would soon be taken care of. Get the Red Menace out of Southeast Asia? Just a few more advisors needed to support the South Vietnamese.

While some of those didn’t exactly work out as planned, that realization was still ahead of us. The expectation that American know-how and money would always bring success is part of the zeitgeist of the era described by A.J. Baime in his enjoyable overview of the foray of the Ford Motor Co into European endurance racing from 1963-1967.

Baime, an executive editor at Playboy, did not write this book for the enthusiast audience. The story of the Ford/Ferrari duel has been told many times over the years and in considerably greater detail in books such as John Allen’s “The Ford that Beat Ferrari” and Anthony Pritchard’s “Ford vs. Ferrari”, but that type of detail wasn’t the author’s intent. In “Go Like Hell” Baime seeks to put a human face on the technological battle, spending most of the book trying to get inside the heads of the key players, Enzo Ferrari, Henry Ford II, and Carroll Shelby, as well as drivers Ken Miles and John Surtees.

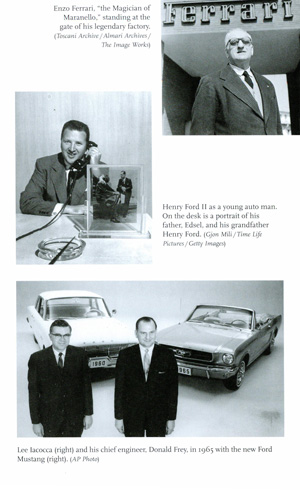

Sample illustrations from “Go Like Hell’.

Descriptions of the breakneck technical advances of the time are certainly there, but carefully abbreviated (particularly on the Ferrari side) to keep the general readers’ eyes from glazing over. Even descriptions of the races, with the exception of Le Mans itself, which is covered in great detail, are very limited.

The book opens with the seemingly requisite description of Levegh’s horrendous accident at Le Mans in 1955, which is not really relevant to the story although the spectre of the danger of motor racing in those times is felt throughout the book. Baime does not get carried away with moralizing about it, but he does feel the need to keep tying in automotive safety, even bringing in Ralph Nader as a side character. He then gives us a picture of the two protagonists, Enzo Ferrari and Henry Ford II, reflected by their reactions to untimely death, Henry to his father Edsel and Enzo to his beloved son, Dino. The author emphasizes how often corporate decisions during this era were still made by single men, with their own strengths, weaknesses, and irrationalities, and it frames the basis of the competition, the infamous failed acquisition of Ferrari by Ford in 1963.

Don’t look for great photography in this book, but it’s a great summer read. Photo from “Go Like Hell”.

However, Baime is careful not to pin the personal vendetta of the slighted Ford against the capricious Italian as the sole reason for Ford’s huge investment in endurance racing, noting that FoMoCo saw Europe as the emerging automotive market of the period, and that it also must be seen in the context of Ford’s efforts to expand market share by winning motor races in North America in NASCAR and USAC as well as the European efforts. Baime ultimately concludes that this worked out pretty well for Ford, based on the continued profitability of Ford’s European operations, although personally, I think Ford got far more bang for the buck from it’s tiny investment in Cosworth, which, of course, resulted in “Ford” being prominently stamped on the cam covers of virtually every Grand Prix winner from 1968 to 1980.

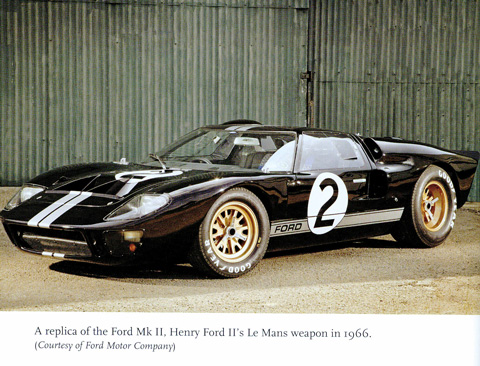

Nearly a third of the book is taken up simply laying the groundwork for the competition. Once we get to Ford’s decision to go ahead with the GT project the book focuses on the personality clashes that cause many of the development difficulties of the Ford team and how they are largely solved by cubic dollars and exotic technologies such as the first CAD based components and on the road computer based sensor and data recording.

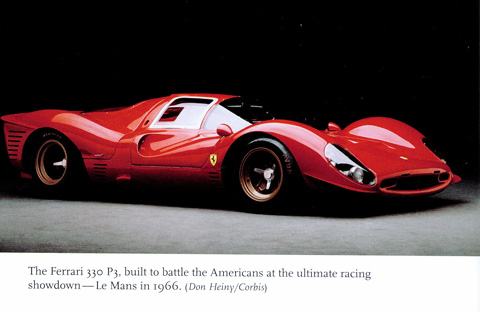

The coverage of Ferrari is more limited, as this is really a book about Ford, not Ferrari, and quixotically centers on the long drawn out Surtees/Dragoni feud that came to a head at the ’66 Le Mans. Surtees seems to be something of a superman to Baime and his replacement by Scarfiotti in the Ferrari lineup is implied to, just maybe, have been the reason that Ferrari finally lost in that event. Many pages are given to describing Surtees’ racing career and even to extensive details of his near fatal accident while practicing in a Lola T70 at Mosport in 1965. In my view, Surtees should really be a footnote to this story. Yes, he was the best in the Ferrari stable during this time, but the effect of any one driver, however talented, on a team as large as Ferrari was not going to make a significant difference. If the author was not going to focus on technical details, why not make the back story for Ferrari be the on-going labor problems plaguing Italy during this period, which severely handicapped Ferrari race preparation, particularly in 1966, which Baime doesn’t even mention? The Surtees/Dragoni story does make for good copy though.

The Ford Mk IV driven by Gurney and Foyt won the 1967 Le Mans, but the Scarfiotti-Parks Ferrari P4 finished second. Photo of the P/3/4 from “Go Like Hell” was taken by Don Heiny, who, coincidentally, is the guy who coined the name “VeloceToday”.

In his descriptions of the Le Mans events themselves Baime writes effectively and in great detail, devoting 18 pages to the 1964 event and 20 pages to the 1965 race. Curiously though, when he gets to the climax of the book, the orchestrated 1-2-3 Ford finish in 1966, he seems to get impatient and rushes through, dismissing the early Ferrari challenges in that race and ignoring the Shelby American/Holman Moody civil war within the Ford camp. Naturally, several pages are spent on the controversial finish where Ken Miles in the lead Ford was instructed to slow down to allow Bruce McLaren to catch up so that a tie for first place could be arranged. As the photos show, he not only did that, but also slowed so much that McLaren passed him just before the finish line. Alas, no more light is shed on just why the notoriously independent Miles gave the race away.

Baime then chooses to end his story with a description of Miles’ still unexplained fatal accident testing the Ford J Car at Riverside a few months later. The 1967 season and the Gurney/Foyt win in the Ford MkIV is relegated to a few sentences in the epilogue. Apparently the author, like Ford, lost interest once the initial prize had been won.

The car that should have won in 1966. The Miles/Hulme GT Mk II at this year’s Kohler Historics at Road America. Photo by Greg Vack.

So will this book add any insight to our understanding of the Ford Ferrari duel? Probably not, although it is admirably researched and footnoted. But if you don’t expect too much, you’ll find Baime tells his story in an accessible, entertaining manner. “Go Like Hell†makes fine summer reading reminding us of a more innocent time when Americans always expected to win.

I thoroughly enjoyed A. J. Baimes book.

I loved the culture clashes that float up through the background of racing, spiraling into that landmark 1966 Le Mans: hot-rodders vs engineers, time vs development, American vs Italian, horsepower vs cylinders, corporate vs casual, global vs national, staid vs flashy, speed vs safety, individual vs team …

There are only a couple of things I have strong issue with; the title isn’t great and should have be more like “Speed, Money & Glory”. Though the inside of the book is well designed, the cover is trash, and could certainly be improved.

I didn’t mind the focus on the Surtees/Ferrari relationship; it added human intrigue to the corporate big picture.

Most of us know this story, and we also know how it ends.

But Baime gives us the behind-the-scenes and the hard to find insights that make it enthralling.

In the interest of full disclosure I published a rival book (Ford GT40 and the New Ford GT) but nevertheless looked forward to reading this book and hope you can find something useful in my opinion. I liked his focus on the people because facts about the cars are so readily available now (such as compression ratio; gear ratios, etc.) ; what is fun to read is what people involved with the team were thinking. I too was disappointed that the author so cavalierly throws away coverage of the ’67 LeMans race compared to his extensive coverage of ’66, and he hardly mentions the fact that the small block GT40s, under John Wyer’s direction, came back and won LeMans in ’68 and ’69 without Ford help. I thought the Surtees battles with Enzo were interesting but would have rather had the same amount of pages devoted to Phil Hill and why he went to the Chaparral team when he had started out with the Ford GT team in ’64. Phil Hill was a complex personality, just as interesting to read about as Surtees and more relevant to this book than Surtees from the American point of view. I liked the author’s salacious revelations about Henry Ford II’s social life (taking up with a blond divorcee while still married)–he researched it more than I did and it’s fun to read how he became “Europeanized” to some extent. I also thought only about half the pictures were new finds, the others I’ve seen everywhere. But the book is a real bargain at the price.

I have yet to read this so can’t comment on Mr Baime’s work, but for a detailed view of the era also take a look at Anthony Pritchard’s Ford vs. Ferrari — the Battle for Le Mans. Zuma 1984, IF you can find a copy. This includes the John Wyer Gulf GT40 years.

BTW, I reckon this was the best time ever for sports car racing, what do you think?

Ford vs. Ferrari, 2nd edition, published by Zuma is available in new old stock form from trueford@aol.com

It covers the LeMans battles from ’64 to ’69 by combining chapters from two different Anthony Pritchard books