Book Review by Pete Vack

In 1969, the Porsche 917 was a scary bit of racecar. High speed stability was not part of the 917’s accessories, and with 630 horsepower and a weight of only 1800 pounds, it was faster than the Formula One cars of the era. When they crashed, they broke in half, right in the middle. According to John Wyer’s chief engineer John Horsman, “The new 917 was extremely unstable and the drivers were unwilling to drive the 917 a second time.”

John Wyer, left, shakes hands with Ferry Porsche in front of a portrait of Ferdinand Porsche. Porsche Archive

By 1970 the 917s were unbeatable. While no doubt Porsche themselves would have resolved the aerodynamic problems that cursed the early cars, it was Wyer and Horsman who got the credit for making the 917 tractable, for in an unusual (for Porsche) partnership forged by Gulf Oil’s Grady Davis, Porsche decided to contract out JWAE (John Wyer Automotive Engineering), late of the championship Gulf Ford GT40s and Mirages, to incorporate the Porsche 917s into his team. The success was as great as the 917s were fast. When it was over, only one driver was actually killed driving a 917, a privateer named John Woolfe at Le Mans in 1969.

Fortunately for us Porsche novices, in his new book, first time author Jay Gillotti lays out the history leading to the 917, as well as a nice chapter on the development of the 917, a project instigated and guided by Ferdinand Piëch and engineer Hans Mezger. The 4.5-liter, flat twelve was based on two of the flat sixes, and posed few problems. The chassis would be an aluminum spaceframe (the last three were magnesium).

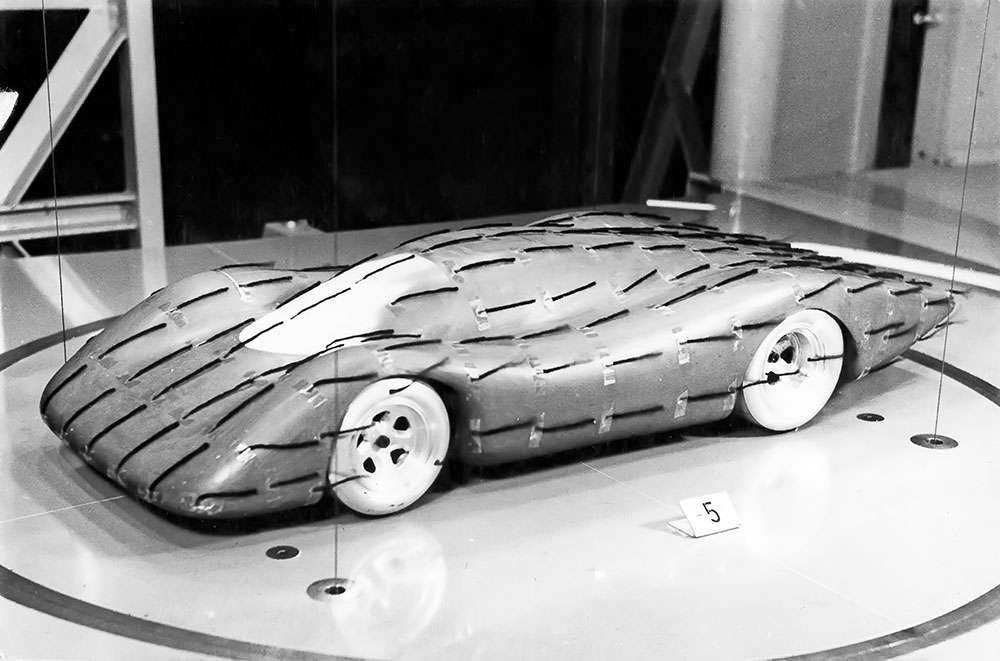

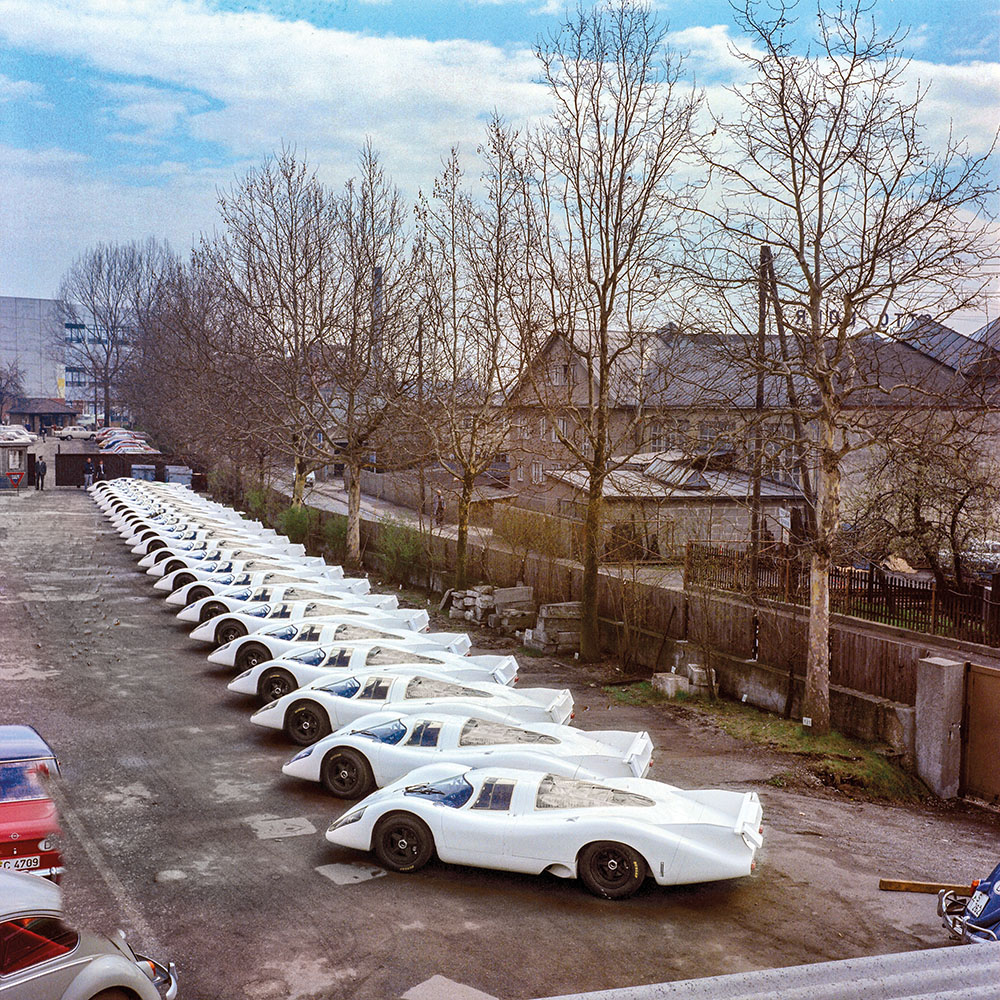

But there would be problems with the design of the body; as smooth as a bar of soap and clean of line, it looked good in the wind tunnel; the first 1/5 scale model test was on July 23, 1968. By the time of the homologation grand show on April 21, 1969, the 917s had sprouted both vertical wings and a small moveable spoiler at the rear. It is unclear how or when those initial aerodynamic devises were added. But they remained that way through the first troublesome year of 1969, until the deal with Gulf had been announced on Septemeber 30, and Horsman began to experiment with a larger, wider rear wing that would prove to make the 917 a manageable, and winning machine. Gillotti details this development with photos and diagrams and it caught our attention.

Why it took Porsche that long to implement downforce aerodynamics is interesting. Porsche engineer Helmut Flegl figured that with the increased speed of the 917, the problem became obvious, unseen with the smaller, slower 908 and 910s from which the 917 was derived. Still, everyone had been experimenting and learning since at least 1962, when Richie Ginther lipped the Ferrari. By ’63 Peter Brock and Ginther agreed that an adjustable spoiler or “wing” might be incorporated one into his initial design of the Cobra Daytona Coupe and fully incorporated it into his P70 Can Am car in 1965. But Brock relates the frustrations trying to incorporate a spoiler or wing in his designs against the wishes of very conservative engineers. It was, after all, hard to give up that slippery bar of soap idea that had originated with the Type 64 Berlin-Rome rally car Porsche designed in 1939. Engineers were conservative, and spoilers, fins, tabs and wings were ugly.

Horsman prevailed. On October 16, 1969, Brian Redman tested the car at Zeltweg with the Horsman tail and continued to take lap after lap, enjoying the car at last. Finally back in the pits, Redman said, “Now it’s a racing car…” At that point the 917s primary competitor, the Ferrari 512, was doomed.

April 21, 1969, the homologation presentation of 25 completed 917s. That had to have shaken up Enzo Ferrari. Porsche Archive

As any Steve McQueen fan can tell you, the 917s just took up and whupped the Ferraris, not only at Le Mans, but everywhere save the exciting Sebring ‘70 when the 917s had front hub problems. For the first time, Porsche achieved the domination in sports car racing in the largest classes. The 917 took Porsche to places they’d never been, and fast.

Jay Gillotti has concentrated only on the chassis that were raced or handled by the Gulf Team in 1970 and 1971, after which the 3-liter rules took effect. This is a chassis number book which is great; but only the chassis as handled by JWAE are in the picture. Little mention is made of the Martini cars, or the Porsche Salzberg Team cars (essentially a Porsche factory team), and of course, one would expect that with the book’s focus. In the Publisher’s Edition (which added another 150 pages and was signed by Derek Bell, Brian Redman, John Horsman and the author), Gillotti does list all known chassis numbers and provides a very brief history of each. Approximately 42 were built with aluminum chassis for endurance racing. A further three magnesium chassis cars were built (051, 052, 053).

In both Editions, Gillotti covers the 917 chassis in detail and discusses another ten chassis numbers by way of incidental connection with JWAE including the Le Mans movie cars. Also in the Publisher’s Edition is a short section on the 917’s opposition, consisting of the Ferrari 512, 312PB, the Matra MS650/660, and the Alfa T33 (the real opposition, placing second to the 917 in the 1971 Manufacturer’s Championship), and the Lola T70. Only 200 copies of the PE were printed and they are almost all gone. Order it now if you want this special copy, which is recommended though more expensive.

Photos throughout are oustanding, both color and black and white. This scene is from Monterey Motorsports Reunion with the 917, chassis 015 taken by Hugues Vanhoolandt.

Though both Martini and Porsche fielded competitive 917s, the Gulf cars were most often the winning cars, taking Porsche to the championship in 1970 and 1971, aided by the Porsche 908 and 910, more suitable to tracks like the Targa Florio. As we have seen, the Ferrari 512s were no match for the Porsches, though they should have been. They clearly meant to achieve their goal of winning the 1970 Le Mans 24 Hours. And, according to Karl Ludvigsen’s The Excellence was Expected, the 917 accounted for 15 of the 24 Championship events won by Porsche between 1969 and 1971. The remainder were won by Porsche 908 and variants.

For each one of the Gulf chassis, there is a separate chapter in Gillotti’s book that includes historical photos, recent vintage race photos, detail shots, race results, and a complete history right up to the present time. The effect is both aesthetically and factually satisfying and as good as it gets when it comes to chassis histories. Gillotti bravely undertakes sorting out and explaining the use of two chassis numbers. For example, chassis 004 was crashed, broke in half, the chassis was then replaced by that of chassis 017, and driven in five more races as 017/004. But the old chassis 004 was rebuilt as a rolling chassis and passed on to David Piper, then eventually to Bruce Canepa who completed restored it and constructed a new body. Therefore, a chapter is devoted to both 004/017 and 017/004.

Food for the McQueen crowd: Actor Carlo Cecchi looks a the remains of chassis 013 during the filming of Le Mans, September 1970. David Piper lost his leg after the accident. Michael Keyser photo.

There are plenty of statistics in the book. The 917 Gulf chassis with the most wins is 034/013 which raced 5 times in 1971, won 4 and finished 2nd once. Next is 016, which in 1970 took first at Brands Hatch, Monza and the Six Hours of Watkins Glen, all driven by the team of Pedro Rodriquez and Leo Kinnunen. Chassis 015 won twice, at Daytona with Rodriquez in 1970 and in 1971 at Keimola Interserie, Kinnunen up. Of note, Rodriguez lost his life at the wheel of a Ferrari 512 in 1971, the little-known Kinnunen died at the age of 73 in 2017.

Needless to say 917s are among the most collectable and valuable race cars today. This Hugues Vanhoolandt photo shows the 917, chassis 031/026, part of the Roald Goethe collection which concentrates on cars run in the Gulf team colors.

Another appendix offers up the Race Data Sheets – clean copies of the JWAE race data information from a number of races, arranged by chassis number. These provide the details of how the car was set up for the event, the weather, oil and gas consumption, drivers, and lap information.

Of course we liked the color photography by VT’s Hugues Vanhoolandt, but overall the book is full of great photography, both contemporary and historical, and typical for Dalton Watson, the layout by Jodi Ellis superb, along with multiple indexes.

Jay Gillotti has done a great job with his first book; we nominate him to be the author of “Porsche 917 vs Ferrari 512” with the same care, detail and enthusiasm he displayed with this book.

Author Biography courtesy Dalton Watson

Jay Gillotti, Originally from Danbury, Connecticut, Jay has lived in the Seattle area for the past twenty years. He began studying motor sport history in high school and worked for his father in a VW-Audi dealership. He has been a fan of Porsche and the 917 ever since seeing Steve McQueen’s film Le Mans as a youngster. After graduating from the University of Connecticut, Jay spent nearly 30 years in the corporate relocation industry before retiring at the end of 2016. He’s a musician and songwriter with self-produced albums available at CDBaby.com/jaygillotti.

Jay was a contributor to motorsport-related books by Michael Keyser (A French Kiss with Death), Christopher Hilton (1982), Brian Redman (Daring Drivers, Deadly Tracks) and Ryan Snodgrass (Turbo 3.0). He is a Porsche Club of America member and contributor to the PCA magazine, Panorama. He has moderated presentations by Brian Redman, John Horsman and Vic Elford for the Porsche Club. Gulf 917 is the result of three decades and more spent researching and gathering information on the Porsche 917, the golden age of sports car racing and the work of JW Automotive Engineering.

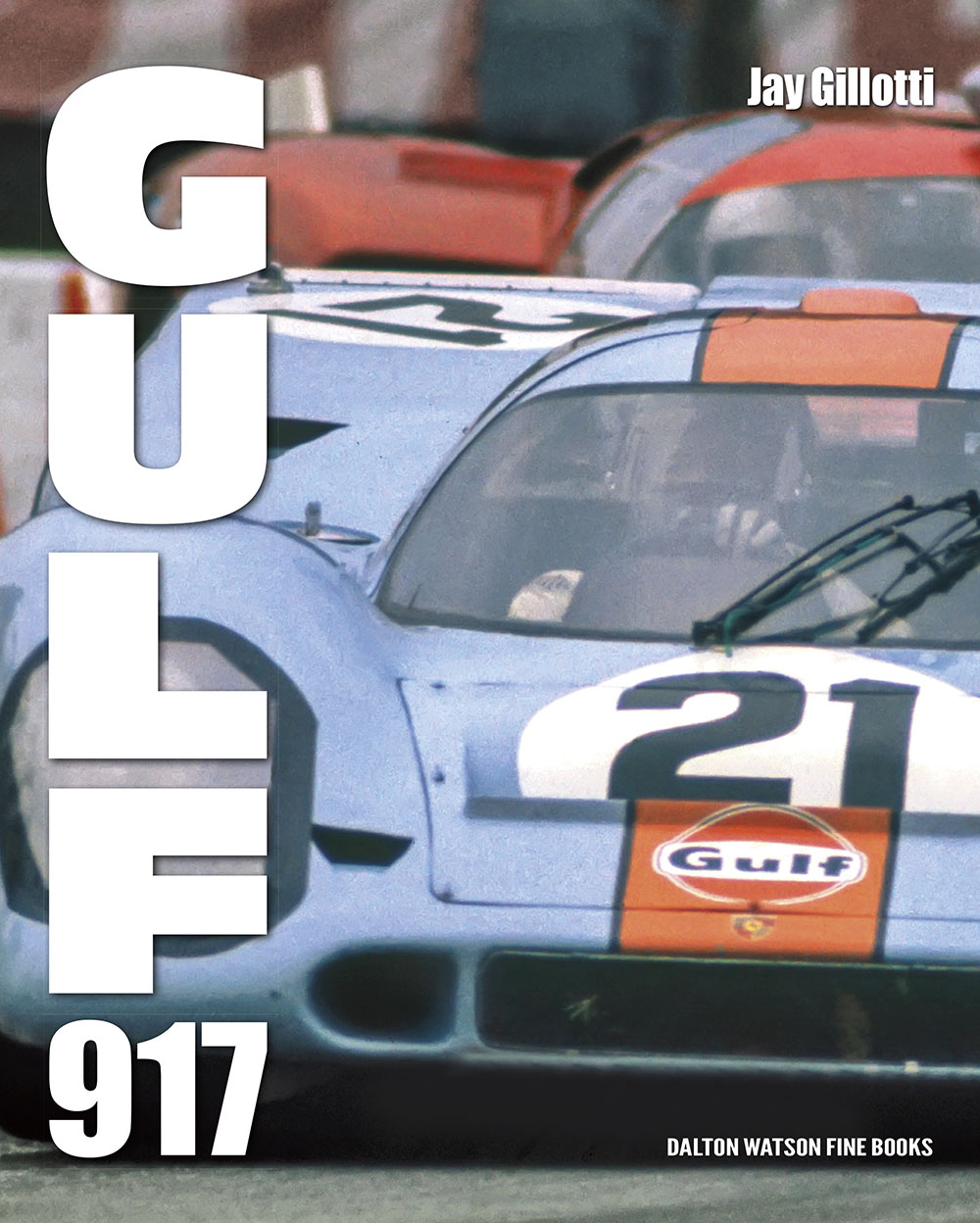

Gulf 917

By Jay Gillotti

Published by Dalton Watson Fine Books, October 2018

Regular Edition

$150 USD

230mm x 280mm

Page count: 496

Images count: 460

Click to Order

Publisher’s edition

$350 USD

230mm x 280mm

Two-volume set with slipcase

200 signed and numbered copies (signed by Derek Bell, Brian Redman, John Horsman and Jay Gillotti)

VOL 1: 496 pages, 460 images, dust jacket

VOL 2: 152 pages, 160 images, dust jacket

Click to Order