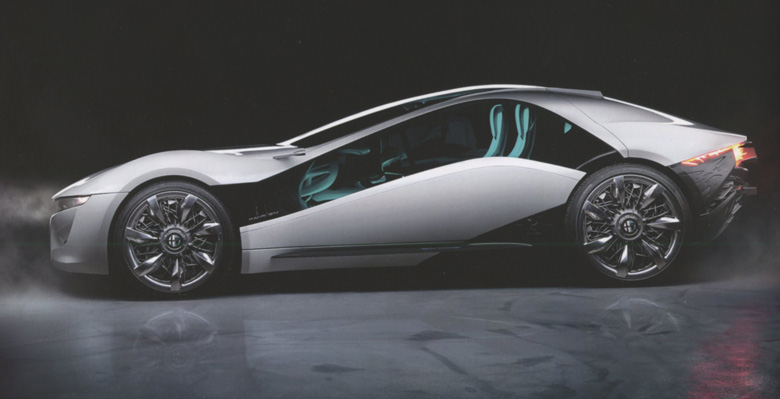

Cream of the crop: Italian design firms still produce wonders, such as the 2010 Alfa Romeo Pandion from Bertone, even if the lead designer was Mike Robinson, an American. The book Italian Coachbuilders includes current design firms as well as those active before WWI.

Review by Pete Vack, comments by Wallace Wyss

All photos from the book

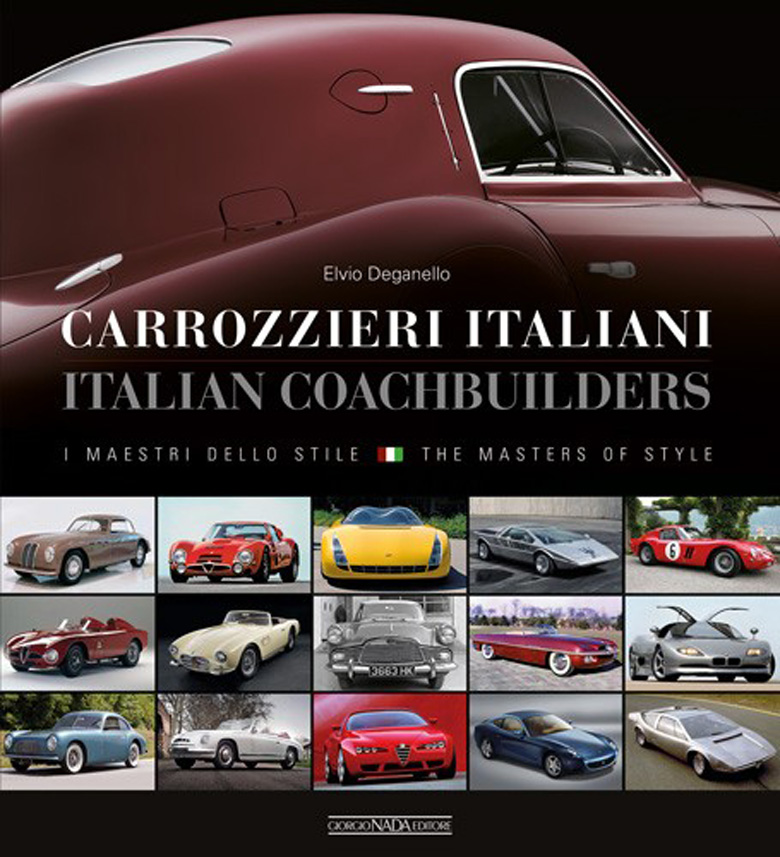

Italian Coachbuilders: The Masters of Style

By Elvio Deganello

408 Pages

1300 Illustrations

10.5 x 11.5 hardbound with slipcover

Text in English and Italian

Publisher: Giorgio Nada

Cost: 70 Euro

Order here from the Publisher

Or at Amazon.com

The body stylists appearing in this book are: Accossato, Ala d’Oro, Allemano, Balbo, Bertone, Boano, Boneschi, Brianza, CA.SA.RO., Canta, Caprera, Castagna, Colli, Coggiola, Coriasco, Ellena, Eurostyle, Faina, Fantuzzi, Filacchione, Fissore, Fona, Fontana, Francis Lombardi, Frua, Garavini, Ghia, I.D.E.A., ItalDesign, Lotti, Maggiora, Mantelli, Marazzi, Mazzanti, Meteor, Michelotti, Monterosa, Montescani, Monviso, Morelli, Moretti, Motto, OSI, Ostuni, Pininfarina, Riva, Savio, Sala, Scaglietti, Scioneri, Siata, Sibona, Sports Cars, Stabilimenti Farina, Touring, Vignale, Viotti, Zagato.

We can’t recall when we were so thoroughly enthused about a book and relentless in our advice to purchase a copy.

Trust us; this is not just another coffee table book about Italian coachbuilders, but as close as we will probably come to a bible. It is 408 pages long with 1300 illustrations in a large 10.5 by 11.5 format and is the most comprehensive, valuable, well-written and well-illustrated book on Italian coachbuilders (in general, not including books on specific coachbuilders). It is written by an Italian whose credentials are impeccable. The author has gone to considerable lengths to achieve the approval of Italy’s most impressive historians and authors and is published by Italy’s leading publisher of automotive books, Giorgio Nada. It is in both Italian and English, with superb translation to English (the best we’ve ever read).

And it is inexpensive. At only $80 USD including shipping at least Stateside, it is the bargain of the year.

The chapters are short. They are concise and not to be considered by any means full histories of an individual firm. Each chapter can’t be but so long, as there are 61 individual coachbuilders covered with ample photos. And that is what makes this book so large, so important, so useful and so good.

On our shelves are many books about Italian coachbuilders, but only one that we are familiar with is anything like Deganello’s opus, and that is the all-Italian language Carrozzeria italiana, cultura e progetto edited by Angelo Tito Anselmi, which lists and very briefly describes 97 Italian coachbuilders in this excellent but slim history from 1978. The authors, however, included many truly obscure firms from before the First World War and added to the total. Deganallo’s effort, on the other hand, concentrates on substantial companies and finds photos to illustrate each one. Nevertheless Deganello includes many of the firms that were most active from 1900 to 1939.

In a very un-Italian style, Deganello’s summary consists of a one page foreward. But in those few words, he describes why era of the Italian coachbuilders existed, to what effect and why they are important, and why they all – virtually every single one – eventually failed.

Monterosa also employed Michelotti, who sketched both of these bodies on a Fiat 600. Constructing these cars kept the Italian coachbuilders financially sound. But you would be hard pressed to find many special bodies Fiats in the U.S..

Clearly the era of the Italian coachbuilders was as Deganello writes, “a unique and unrepeatable phenomenon in automotive history.” Deganello adroitly explains that after World War II, the pressing need of the major European manufacturers to increase their model ranges left coachbuilders the market for special versions, satisfying demand for individual accessories, paint, and options as well as styles. This is something which the larger manufacturers in the world quickly adopted to their own production lines, but for Italy in the 1950s, the coachbuilders were essential.

Deganello asserts that the French were unwilling to do much in the way of coachwork on everyday vehicles, concentrating on the dying luxury car trade; the Germans had few such firms before the war and certainly fewer after, while the British were, aside from Jaguar and a few others, far too traditional despite capable cottage industries.

This left the way for Italian coachbuilders to flourish in a market starved for both cars and individuality, allowing their inherited art and craftsmanship to create thousands of special bodied, often beautiful, designs on not only Fiats but French, German, English, and American makes as well.

However, most of the Fiat special-bodied cars – and they were by far in the majority as that was the bread and butter – were made and sold for the home market. A look through the 408 pages will make it clear to most Americans familiar with the era that most of the Fiat confections never made it to these shores in any numbers during the 1950s. But the Pinin Farinas, Bertones, Vignales that adorned the Ferraris, Maseratis and Alfas we did import to the U.S. had an influence that belied their few numbers and high cost, and made the Italian coachbuilders both famous and, for a while, wealthy. The essence of this particular Italian miracle was Fiat, not Ferrari or Maserati. And, perhaps too much emphasis can be place upon the famous designs, ignoring the more significant economic impact made by the thousands of coachbuilt Fiat 1100s. Outside of Italy, fantastic coachwork was all oohs and ahs; within Italy, it was business and employment.

More can be ascertained from the text itself. For example, the majority of the 61 firms listed had entrepreneurs who were born around the turn of the century. They grew up with the automobile, had vast experience before WWII, and when the good years came in 1947, they were primed and ready to take advantage of the new opportunities. They were not overnight success stories but the result of training and hard work.

A scene from the chapter on Balbo. #10 and 11 are Fiat 1500s from 1949, 12 are Michelotti sketches for the Fiat 1400 and 13 is the realization in 1951 of the 1400 couple. All photos in the book have in-depth captions in both English and Italian.

Another element was that a few of the very brightest designers such as Giovanni Michelotti and Franco Scaglione – were employed or contracted by many of the smaller coachbuilders. In the case of Michelotti, Allemano, Balbo, Viotti, OSI, Stablimenti Farina (who gave Michelotti his start), Vignale, (where he gained fame), and Fissore all used Michelotti drawings. Perhaps no one individual had more overall influence in the postwar era than Giovanni Michelotti.

The boom years were from 1955, when about 20 Italian coachbuilders were producing about 6000 cars a year. By 1965, less than half of that number of firms were producing a far greater number of cars due to further industrialization; Bertone and Pininfarina output alone exceeding 6000.

The Italian coachbuilders almost all died at about the same time – between 1965 and 1980 – from multiple wounds inflicted from a variety of sources. Both Bertone and Pininfarina quickly adapted to the increasing industrialization of coachbuilding, and both succeeded for a few more years than the smaller firms with little or no money for that kind of investment, but today even Bertone and Pininfarina no longer build car bodies.

Deganello writes, “I believe that the Italian people have significantly underrated the incredible story of the nation’s coachbuilders and that even abroad awareness and understanding of the phenomenon is limited.” We think he has that backwards, but in either event, we fully agree with his concerns and his book will go a long way toward increasing the public’s knowledge of Italian coachbuilders.

On the down side, for some reason the book has no index, no bibliography, and no direct documentation of sources when quoting. As the book, it seems to us, is most beneficial to automobile historians and researchers, the lack of these essentials is a sad oversight. That said, the book is a must have, despite these omissions.

We have Wallace Wyss to thank for bringing our attention to this book. Wyss submitted such an enticing review we knew we had to get a copy for ourselves. We think he makes some salient points in his review, from which we quote below:

We scribes who write about Italian design were, before this book, often working in the dark. Oh, we knew the names of various coachbuilders, and could get the easy-to-find stuff (Bertone press pictures, Pininfarina press pictures) but this book goes way beyond the easy-to-find into the truly obscure. The main value of the book, I think, is the rare photos. They contrast, almost jarringly with more recent color pictures. It’s a treasure trove of never-before-seen pictures. Occasionally there is a picture that is spread across two pages like that of the Boano-bodied Lincoln Indianapolis.

Every page is a revelation. And the English text is well written. Even in the first entry you learn more than you’ve read in a dozen articles; “…the 1964 crisis meant Carrozzeria Allemano was too small to be a manufacturer and too big to be an artisan,” thus explaining why the coachbuilder closed its doors.

One of my favorites included here is Fantuzzi, whose prewar stuff they show, plus some of the oddball cars like his prototype Testa Rossa (full fendered-SN 0766) as well as a couple of prototypes for DeTomaso (P70).

Fissore is another old line house where the author begins with the 1950s and works his way up, one of their most famous jobs being the Monteverdi Hai and the Monteverdi Palm Beach. OSI is a mysterious firm that doesn’t get much credit, but it was started by Ghia man Luigi Segre. Frua gets some space, but Frua alas isn’t as well-known because around 1957 he went to Ghia to become head of design and was then fired. He went back to freelancing. Now I didn’t think of Scaglietti as a coachbuilder; I know he was a body repairman when first hired by Ferrari but he was an independent coachbuilder whose main customer was Ferrari.

Another oddball coachbuilder was Sibona & Basano. They banged out the Kelly Corvette, designed by Alfredo Vignale but “farmed out “ to Bassano, who was his son in law. But of course the most magnificent car (in my opinion) of all maybe in the whole book is their Bizzarrini Targa they did for Stile Italia.

Monterosa made woodies too, this one on a Fiat 1100. But in almost all cases, the wood was painted metal.

Carrozzeria Drogo is called Sports Cars not Carrozzeria Drogo and they were another shop that made money rebuilding wrecks until they did their own cars. They did the Ferrari “breadvan”, the ASA GTC and according to this book the Maserati Tipo 151/4 chassis similar to the one Moss raced at LeMans, not to mention work for Tom Meade, the American who re-invented himself as a car designer in Italy. You think woodies, you don’t think Italian but in the Monterosa chapter displays their woody wagons.

All in all, it is a magnificent book and I simply can’t imagine any automotive writer or Italian car restorer or even sports car designer not having this book on their shelf.

Me again. Buy the book, you will be in awe. Go directly to Giorgio Nada or find it on Amazon or Alibris.

When Italians do something, they do it better. A few weeks after Deganello’s book another epochal work was published about Italian coachbuilders: “The Encyclopedia of Italian Coachbuilders” by Alessandro Sannia, a known Italian historian, author and publisher, a member of Aisa and Sah.

The two-tome, large size, slipcased encyclopedia is available in two version: Italian and English (the best English I ever read in an Italian book). It spans over 654 pages with many thousands photos, indexes, and bibliography. Did someone know of coachbuilders in Sicily or Apulia? Here they are alongside the known ones: e.g., Bertone has 18 pages illustrated with 140 photos of different vehicles.

I must agree with the comments of Mr. Vack and Mr.Wyss. Elvio Deganello has created a masterpiece of history, art, and interest. The effort that must have gone into the research for this book is staggering, and the product is fascinating, informative, and a delight to the eye. “Carrozzeria Italiani” is worth more than twice the asking price, and will be prized by anyone who is interested in automobiles. The true shame is that Italian coachbuilding has died a slow and miserable death. There are still designers, but no more builders.

Great article on a fine book,just one nit to pick : forward = opposite of backward,

intro to a book = foreword.

Keep up the good work,

Michel Van Peel