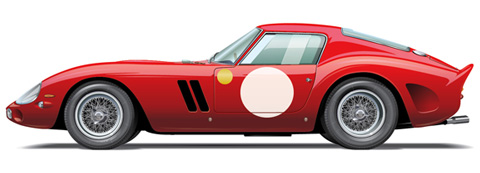

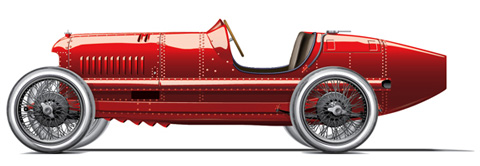

Below drawings by Steven Cavalieri.

A delightful introduction to Italian racing history

Review by Pete Vack

Italian Racing Red’s somewhat simplistic title implies another general potboiler. But a book written and researched by Karl Ludvigsen, author of Porsche, Excellence Was Expected and Mercedes-Benz Racing Cars as cannot be so easily written off.

In only 175 pages Italian Racing Red attempts to review 160 years of Italian racing cars, designers, and manufacturers, an almost impossible, unenviable task. Nevertheless, Ludvigsen has written a book which serves as an introduction for newcomers, yet covers the subject adequately with a surprising amount of interesting insights enough to keep the well informed even better informed. Our opinion of the book went from disparagement to delight after consuming the all-too-short text.

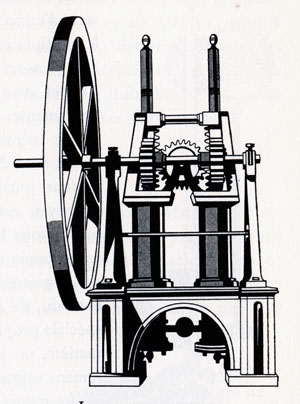

The two cylinder Barsanti/Matteucci

engine of 1857, which preceeded Otto’s

patents by five years.

Starting in the middle of the 19th century, he reminds those who have forgotten, and tells those who did not know, about the Italian role in the invention of the automobile and the internal combustion engine. As Ludvigsen points out, according to historian Lyle Cummins (the son of Chessie Cummins, founder of Cummins Diesel) “Only an act of fate prevented two sons of Italy from being remembered as the founders of the I-C engine industry.” Two scientists working in Florence, Felice Matteucci and Eugenio Barsanti, patented the first working efficient internal combustion engine in London (Patent Number 1072) in 1854 and 1857, far in advance of Otto’s similar engine in 1862 and the four stroke in 1876. Barsanti’s untimely death of typhoid (the act of fate referred to by Cummins) and the failure of Matteucci to series produce the engine allowed Otto to gain the spoils of development and further invention. But it was the Italians, not the Germans, who paved the way for the practical ICE.

Ludvigsen approaches the subject with a human, social and technical perspective. He describes the ubiquitous and talented Ceirano brothers, Giovan and Giovanni, who from 1899 to the 1925, were involved in the construction and or design of a remarkable number of Italian cars, including the Welleyes (Anglo name was pure PR), Fiat, SCAT, Itala and the Spa. A chapter on industrialists at the turn of the century reveals that Turin was notable not only for its craftsmen, but for the discovery of a vein of rich iron ore, located northwest of Turin in the Aosta Valley. The Cogne works not only demanded the installation of an electric grid, but soon were producing high quality steel alloys, “…just what was needed for the crankshafts, gears, and connecting rods of Italy’s racing cars.” Ludvigsen included a sidebar (one of many interesting and informative set-offs) on Pirelli, a firm which came to the forefront after equipping the winning Itala in the Paris-Peking epic of 1907.

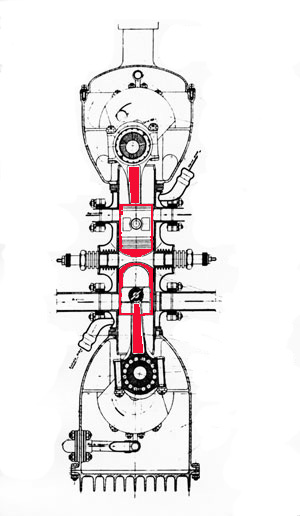

The “Head Knocker” Fiat experimental two

stroke Grand Prix engine. We have taken

the liberty of outling the pistons in red.

Another sidebar of note illustrates the Fiat Type 451, designed for the marvelous but expensive 1.5 formula of 1926. Truly a “boxer” engine, the 451 was a two stroke six cylinder, and within each cylinder were two pistons which met each other head on. This was discarded, and the U12, with three overhead camshafts, eventually powered the last Grand Prix Fiat, the Type 806.

The successful 2 liter 1923 Fiat 805 was designed by Vittorio Jano, who soon left to become Alfa Romeo’s chief engineer (the Jano Alfa P2 would be an 805 Xerox.) Ludvigsen notes that Jano’s name is pronounced “Yarno” as in Jarno Trulli. Whatever the name, Jano had a pronounced impact on Alfa Romeo and the story of Fiat’s racing demise and the rise of Alfa Romeo is well told.

Between the chapters on Alfa and Maserati, “Feisty Independents” takes a look at the lesser known race cars of the 1920s. The 93 hp 1500 cc DOHC supercharged Chiribiri, for example, was Nuvolari’s first four wheel competition machine; you’ve heard of Fiat, but what about FAST, an appropriate acronym for Fabbrica Automobili Sport Torino; the first winner of the Mille Miglia, the OM, was a company that also produced a 1.5 liter DOHC for the 1926 Grand Prix season dominated by the Delage team.

Often overlooked is the San Giusto, a 1924 sports car with a backbone frame much like the Lotus Elan’s, four wheel independent suspension, powered by a rear engined four cylinder air cooled engine and four speed transmission. “A great lost opportunity for Italian motor sports”, writes the author.

Rare photo of Mussolini sitting in an Alfa Romeo P3. Italian Racing Red is full of neat and surprising bits of information, photos and diagrams.

Rare photo of Mussolini sitting in an Alfa Romeo P3. Italian Racing Red is full of neat and surprising bits of information, photos and diagrams.

As the years unfold, Ludvigsen continues to present the material in his unique technical-social manner and manages to throw in even more little known facts or photos (the photo of Mussolini sitting in a P3 is rarely published!). Did Jano really get the idea of back to back fours with a central cam drive from the 1928 Salmson? And wouldn’t we all like to know more about the Furmanik record Maserati of 1938?

Probably for space reasons, don’t look for a great deal of information about Fiat based specials such as Bandinis, Taraschis, and Erminis. Despite an interesting chapter on ‘etceterinis’ in which OSCA, Lancia and Abarth are addressed, most of the wee ones didn’t make the final grid.

While covering the achievements of Maserati, Lancia, and Ferrari in the post war era, the author does not neglect the smaller, but important manufacturers which have ably represented Italy in sports, grand touring and endurance racing up to the present time.

The last chapter which relates the impressive Formula 1 victories achieved by Ferrari in the past ten years. Despite a lackluster season so far, we might recall that Ferrari won the World Championship in 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003 and 2004, and 2007, while as we all achingly watched last year, Massa lost by only one point to Lewis Hamilton.

Cars like the F2 Minardi, here driven by Alboreto, are not overlooked despite the brevity of the book.

Seemingly uneven at times, Italian Racing Red suffers only by the lack of length. The subject could easily fill ten volumes; to have done a credible, interesting and informative job in such a slim volume is remarkable. The only book we can think of which can compare to it Pritchard’s Competition Cars of Italy, and Ludvigsen’s version offers a far wider and more introspective story.

Throughout the text the many rare b&w and color photos are augmented with the excellent profiles of selected cars by Steven Cavalieri. His work is clean, crisp, elegant and captures the essence of the cars. We wish there were more.

There is a detailed index, a bibliography, and most sources are mentioned in the text, eliminating the need for footnotes. Italian Racing Red is the first of a four-book series covering British, French and German cars with similar titles.

But, would we buy the book? For only $47, yes, and we’d bet that it will become a very handy reference book as well. We look forward to the rest of the “color” books as well.

Italian Racing Red

By Karl Ludvigsen

Ian Allan Publishing Ltd. Hershan, Surrey, Great Britian 2008

176 pages, 150 color and B&W photography, Hardback

ISBN(13) 978 1 7110 3331 3

$46.95 USD

Order from: www.Ianallanpublishing.com

This has to be one of your best article ever published. It is very informative. I learned a lot form it and will look for the book.

Thanks, Nick

Thanks for informing us about this book. Please note that some minor slips of the pen appeared in your review: Cerano has to be Ceirano and Cone was the Cogne metallurgical industry.

Another terrific book review that will send me scrambling to add this book to my collection….

Veloce Today is now my favorite reason to sign on to the internet. Keep up the excellent writing!

Mary Ann Dickinson

Pete,

A very good review on a worthwhile addition to an already overloaded bookshelf. One minor correction: The Cummins Diesel founder and his son both bear the same name. It is Clessie Lyle Cummins. C. Lyle Cummins, Jr’s book “Internal Fire” is a standard reference on the history of the internal combustion engine.

For those who would like to know more especially about the racing Fiats, I have just released a book dedicated to the subject: “Fiat en Grand Prix 1920-1930” (sorry… it is in French!). See the following link:

http://www.librairie-passionautomobile.com/Item/13_0748_this.aspx

The book includes all historical and technical details about the 801, 802, 803, 804, 805 and 806 GP cars as well as the 451 two-stroke engine. It also tells in detail the life and involvement of Giulio Cesare Cappa, Tranquillo Zerbi, Vincenzo Bertarione and Vittorio Jano (to be pronounced “Yano”, without an “r”).

Caution: neither Vincenzo Bertarione nor Vittorio Jano were the fathers of any racing Fiat. At Fiat, both of them were only technicians, working on cars designed firstly by Giulio Cesare Cappa and then by Tranquillo Zerbi.