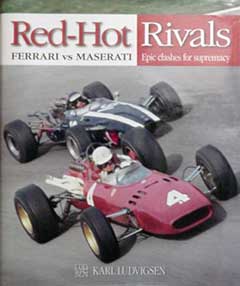

Red Hot Rivals: Ferrari vs Maserati

Epic Clashes for Supremacy

By Karl Ludvigsen, Haynes Publishing, Somerset, England

Hardcover, 336 pages

ISBN 987 1 84425 412 5

$54.95 USD

Book Review by Pete Vack

Nino Farina in the Ferrari battles with the Maserati of Marimon at the 1953 British G.P. Close battles were the norm for the 1952-53 season.

It is amazing, in a world filled with remarkably good books on Ferrari and an increasing number about Maserati, that yet another volume has arrived to dance in what seems like a very crowded ballroom.

Onto the floor comes Karl Ludvigsen, who takes a stab at a subject which is at the same time very obvious and yet almost totally ignored; the longtime, often vicious rivalry between Maserati and Ferrari that took place from 1947 to 1967. What began as a series of articles for “Forza” magazine eventually was expanded into an excellent book.

Long known for his superb mastery of technical subjects (read His Excellence is Expected), Karl embraced the subject with the same youthful enthusiasm and technical expertise as he did 52 years ago in the pages of “Sports Cars Illustrated” when he provided the first complete technical description of a Ferrari Monza. Ludvigsen possesses a deep well of experience and knowledge and uses it wisely. Rarely, if ever, have automotive writers been able to assimilate complex technical information with race results and historical information in one book, one paragraph and indeed, often combining all three into one well-constructed sentence.

Franco Rol’s 4.5 liter OSCA Type G, April 6th 1952 at Turin. The big OSCA could have been a serious threat to Ferrari.

To say that the book is profusely illustrated is an understatement. In addition to the standard Ludvigsen text, he makes good use of his Library, which contains the photograph collections of the great Rodolfo Mailander (see our review of Ferrari by Mailander), Edward Eves, Max LeGrand, and Stanley Rosenthall. Of course many of the photos have been published elsewhere, but many were new to this reviewer, and so intricately tied with the subject even old photos take on a new meaning, helped by long and informative captions. In addition, many photos are rare period color images.

Both a plus and a minus for the book is the chapter layout, which is a model by model comparison, i.e., the 125 F1 Ferrari vs. the 4CLT/48, the 166 SC vs. the A6GCS, etc. to the final chapter which pits the Ferrari 312 against the Cooper Maserati. As Ludvigsen writes in the Preface, “Depicting the rivalry model by model inevitably leads to some chronological overlap.” We used the same organization while comparing the Ferrari-Maserati Sports models for an article for “Viale Ciro Menotti”, and we agree that a model by model comparison is the only effective and interesting way to present the material. Throughout the chapters, Ludvigsen is well aware of potential for repetition and does not let this occur, at least verbatim.

Unlike our brief article, however, Ludvisgen goes everywhere and does everything in his book. He explores every aspect of the competition that started in the early 1930s, when the Maserati brothers first lured Achille Varzi into their camp, then captured the great Tazio Nuvolari’s loyalty in 1933. It was just one of the many factors that led to bad blood between Enzo Ferrari and Maserati. The feud carried over to the Orsi family as well. Ferrari, according to Brock Yates, thought the Orsis were “interlopers on his turf and below his station.” When in 1938 the Orsis bought out Maserati and moved the firm from Bologna to Modena, Enzo must have been beside himself.

The author takes us down unexpected back alleys, and includes comparisons with OSCA as well as Maserati. Having made two enemies, Ferrari then fought a war on two fronts as the Maserati brothers left the Orsis and formed OSCA. Ludvigsen then follows through with a chapter devoted to the OSCA G-Type (G for Gordini, who initially funded the project) which posed a potentially significant threat to Ferrari with a new and innovative 4.5 liter V12; given a little more time and money, OSCA V12s may have defeated the big Lampredi Ferraris. OSCA 2 liter sixes also provided a threat in the Formula 2 events of the early fifties, where Ferrari faced stiff opposition from the Orsi’s Maseratis as well.

Ferrari’s 315S, here at Sebring 1957, at 3.8 liters, was not enough to effectively challenge the 450S. The 4.0 liter 335S was the next step.

Scanning the pages of history, it appears that Ferrari won most of the races, the championships, the fame, and whatever fortune was to be had in those days. Maserati is perceived as the bridesmaid, the second sister, the also-ran who seldom achieved greatness.

Ludvigsen reminds us that Maserati was far from unsuccessful, and that luck had more to do with Ferrari victories than with sheer speed or technical superiority. Ferrari seemed blessed by luck, Maserati plagued by the lack of it. A few Maserati hard luck stories; the core of the company, the Maserati brothers, left in 1947 to establish OSCA; financial problems closed the factory for several months in 1949; after wisely signing Fangio for 1952, the Argentinean had the only serious accident of his career and was out for the entire season, effectively giving the Ferrari of Ascari free reign; the sudden end of the Korean War in 1953 left Maserati with no customers for its machine tools; Stirling Moss, who would always rather drive for Maserati than Ferrari, was signed by Mercedes-Benz in 1955, joining another Maserati regular Juan Fangio; Ferrari was the beneficiary of the Lancia F1 cars in 1956 while Maserati was forced to continue to develop the 250F; and finally, the catastrophe at Caracas in 1957 which ended Maserati’s hopes for the World Championship of Makes. Misfortunes seemed to be part of Maserati’s brief.

Looking back at those years, we recall that Ferrari’s Alberto Ascari seemingly totally dominated the 1952 and 1953 F1 seasons with the superb Lampredi 500 four cylinder. (Ludvigsen had noted in 1956 that the two liter four was developed because Enzo Ferrari was very impressed with the 1950 performances of the four cylinder British HWM, particularly in the hands of Stirling Moss, and he reiterates this in “Red Hot Rivals”.) Ascari’s victories, with all due credit, were accompanied by some of the closest racing in Grand Prix history. After a brief interlude of domination by Mercedes-Benz, the Italians got it on again in 1956 and 1957 in both F1 and sports racing, competing often bitterly for the championships.

Watkins Glen, 1966. Lorenzo Bandini in the 36 valve 312F1. The great rivalry was coming to a close.

Though somewhat abated, the great rivalry didn’t stop when Maserati retired from racing in 1958. Guerino Bertocchi was still very much a part of the Orsi organization, as was a still young and eager engineer by the name of Giulio Alfieri who had joined Maserati in 1953. Even before Maserati was back on its feet financially, (mostly due to the sales of the 3500GT) the pair were plotting for a return to racing, even if it had to be supported externally by the likes of Briggs Cunningham, John Simone, Charles and John Cooper and Lucky Casner. The two and three liter Maserati Birdcages were the last sports Maseratis to provide effective competition for Ferrari, but Ludvigsen also takes a fresh look at the Maseratis which followed the Tipo 61, and comparisons to the successful Chiti designed Ferraris are informative and complete.

For the new three liter Formula 1 in 1966, Maserati designed and built V12 engines to shoehorn into Cooper chassis. John Surtees managed a win with the hybrid at Mexico in 1966 and in January 1967 Pedro Rodriguez won the South African Grand Prix. But it was only half a Maserati and by the end of 1967, the Cooper-Maserati period came to an end. The great rivalry was finally over.

With a Coda chapter, Ludvigsen takes the Ferrari-Maserati war to the very end, when in 1999, Ferrari took control of an ailing Maserati and pumped new life into its rival. We are able to see the struggle from its inception in the 1930s to 2006, when Maserati was brought under the Fiat family.

Not forgotten but attenuated was the U.S. racing scene, which from the early fifties to the mid sixties was a Ferrari/Maserati battleground. A wide variety of Maseratis from the A6GCS to the thundering 450S were hounding the appropriate Ferraris on tracks across the country; Jim Hall, Carroll Shelby, Bob Drake and many more all raced Maseratis and did so very successfully. A subject for another book? Or perhaps such a book might be combined with Ferrari vs. Maserati road cars.

When Ludvigsen first wrote about the Ferrari Monza he stated that “Various early Monzas were bodied by Autodromo”. Ludvigsen noted in “Red Hot Rivals” that Ferrari historian Antoine Prunet “suggests that this [Autodromo] may have been related to the race in which the car made its debut, not to its coachbuilder. He also surmises that Scaglietti may have helped create its body.” Karl Ludvigsen is rarely wrong, but always the perfectionist with a long memory, makes sure the record is set straight, even fifty-odd years after the fact.

Ideally, we’d like to have seen more chapter subdivisions, tables listing the comparative specs of the models addressed, more serial numbers, and perhaps an appendix listing Ferrari/Maserati results in the major races by year. On the other hand, there is an excellent three part index, (Cars and Teams, Circuits and Races, and People) the binding, paper, printing and overall quality of the book is excellent, and there is no doubt in our mind that Ludvigsen’s book is not only a welcome addition to the library but an essential one.