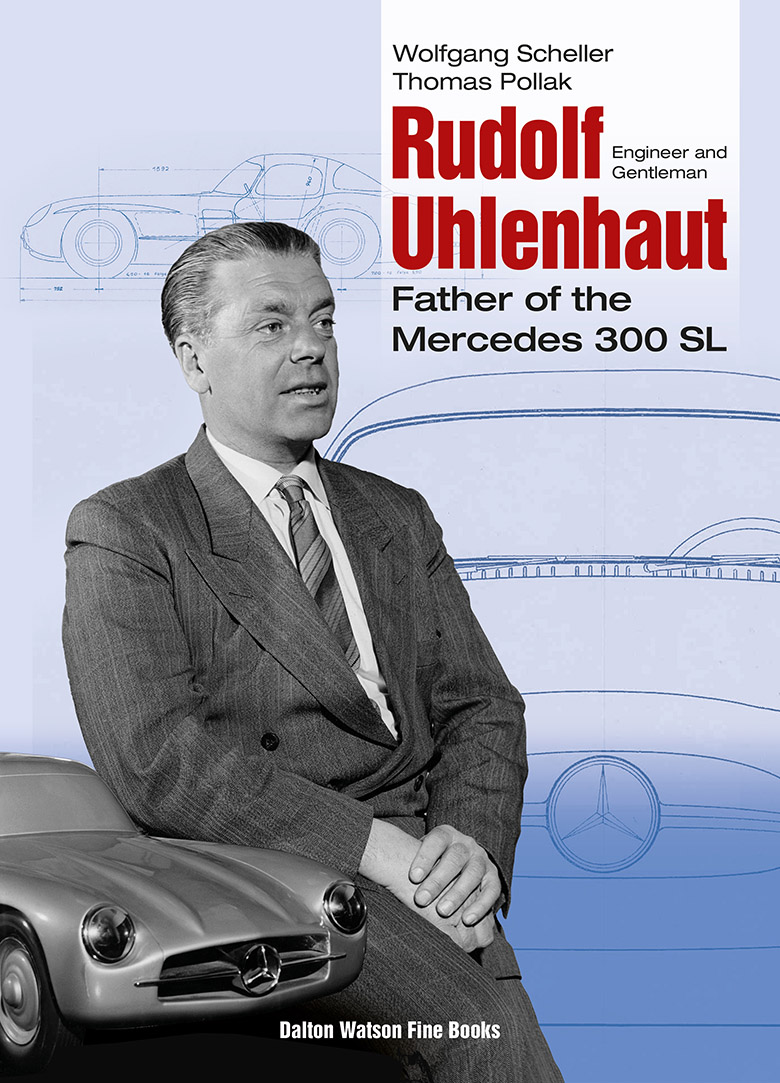

Rudolf Uhlenhaut: Engineer and Gentleman

By Wolfgang Scheller and Thomas Pollak

Translated by Carmen Pollak

Dalton Watson, March 2017

ISBN 978-1-85443-282-7

304 mm by 219 mm 308 Pages, 296 illustrations

Hardcover with dust jacket

US $89 plus shipping

Review by Pete Vack

All photos from the book with the permission of the publisher

Rudolf Uhlenhaut: Engineer and Gentleman by Wolfgang Scheller and Thomas Pollak is the latest book from Dalton Watson Fine Books, a publisher who now seems to be (thankfully) promoting books on automotive personalities. Two recent books were Thrill of the Chase and Marcello Gandini. While Uhlenhaut does not quite measure up to the previous books from Dalton, because of the subject matter, it is a very welcome addition to the library.

Uhlenhaut was a man who excelled at being at the right time and the right place while taking full advantage of the opportunities that lay before him. Half German and half English, he was raised in London, Brussels and Germany, was multilingual, multicultural, extremely well educated, urbane and modest, a quiet family man who loved to sail and ski. During WW2 he worked in the German occupied territories on a variety of Daimler-Benz projects and emerged sane and sound to rejoin the company at Stuttgart in 1948, retiring in 1976. And of course, he was a hell of an engineer.

Of interest to our readers was the fact that many of Uhlenhaut’s years as a test engineer were taken up trying to figure out how to keep the power on the road. Independent rear suspension – in those pre-Chapman years limited to a variety of swing axle arrangements was the answer, but rarely a satisfactory one. The Italians had the same problems, and as Peter Darnall recently suggested, Jano even sent Giovanni Guidotti to Porsche for some much needed advice. ( Read A Most Unusual Meeting).

Test driving racing cars in those days was dangerous, somewhat akin to being an aircraft test pilot. One didn’t know how the machine would behave or what the limits were. Very few drivers could relate those problems to the engineers, who often had another problem; many didn’t drive at all! In 1931 when Rudolf Uhlenhaut was first employed by Daimler-Benz, according to the authors, he was the only engineer with a driver’s license. He made the most of that opportunity!

Fast rising star: An undated photo (circa 1936) of a very young Uhlenhaut in the center of the Mercedes Racing Department. He was only 30 years old when promoted to the position of Chief Engineer in Neubauer’s Racing Department.

Promoted to the Chief Engineer of the Racing Division in 1936, to find out more about how racing cars handled and performed and to be able to evaluate the opinions of the drivers, “I’d have to sit where they did, ” recalled Uhlenhaut. Mercedes was having a totally miserable year with their 1935 W25. The new Auto Union C type and the Alfa 8 and 12 C Grand Prix cars were making life miserable. (Read the 8C 35 Grand Prix Cars ) In August of 1936 Uhlenhaut decided to get behind the wheel of a 1935 450hp Mercedes-Benz W25 at the Nurburgring. “It was a dreadful apprenticeship,” he later admitted. He put in over 300 laps, about 4000 miles, and got to know the car and how it might be improved.

As Karl Ludvigsen pointed out, test driving road and race cars was not unique; Lancia, Chapman, Maserati, (and we add Lefebvre) and others were also race drivers or record breakers. And all were good for the company’s PR efforts. But Uhlenhaut’s record, his successes, his ability to drive any kind of an automobile, combined with his good looks, accessibility, his ability to converse in English and other languages, and shear longevity made his career remarkable.

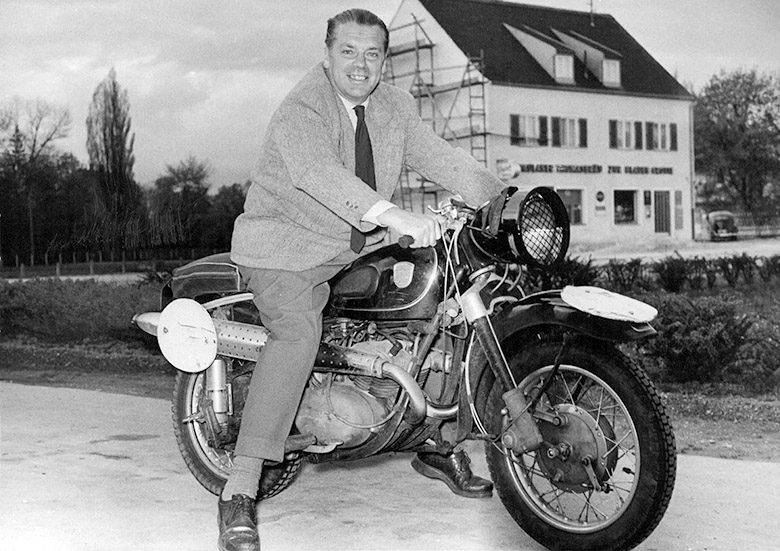

In addition to sailing and skiing, Uhlenhaut loved motorcycles and always preferred to travel on two wheels when possible. Here on his Adler MB 250, 1955.

The authors presented two facets of Uhlenhaut, the man (gentleman) and his work (technical progress).

The Gentleman

In the introduction, the authors admitted the reason there is so little known about Uhlenhaut was due to his ‘discretion about his private life”. And the Uhlenhaut grandchildren respected the fact that Uhlenhaut “did not want a biography to be written about him”. It’s not that he had anything to hide, but he sought to keep the publicity generated by his career (which was ample) and his desire to keep his private life private. And despite his public persona and fame, he was not willing to succumb to the cult of the personality. Yet, we yearn to know more about the man, a desire fed by the publicity and accomplishments he achieved in his roles as a test and experimental engineer.

Fortunately the authors, thanks to the family, were able to provide enough new material to fill a good part of the book. From his childhood in London there are photos of his house, his father (a director at London’s branch of Deutschen Bank), from WW1 in Berlin to the Hansa-Lloyd factory where Uhlenhaut spent his summers as an apprentice, later at the Technische Hochschule in Munich. There are records, photos, graduation documents and insights. There are omissions; although he was a dedicated husband and family man, the authors point out that they did not find a marriage date, or any photos of the marriage ceremony to a legal secretary named Edith Gottschlag in 1935. And, apparently the family stopped short of providing any letters or diaries.

Once employed by Daimler-Benz in 1931 (Uhlenhaut’s technical training must have impressed; he was one of the few new hires in that Depression year) the book’s emphasis shifts to his work at Daimler-Benz and personal information is much less forthcoming.

Technical Progress

What exactly is the job of an automotive test, development, and experimental engineer? What were his accomplishments in this field? Did he have any patents to his name? Did he, for example, actually design the 300SL space frame? To address these questions, the authors have four sections of the book devoted to “Technical Progress”.

The book tells us about the technical innovations and his achievements in the pre war years, his war years living in German Occupied Czechoslovakia and back with Daimler-Benz from 1948 to 1972. To better understand what he was responsible for at Daimler-Benz, from 1936 to 1939 he was the Chief Engineer of the Racing Car Department; from 1949 to 1959 he was the head of the Experimental Department; from 1959 to 1972 Uhlenhaut was a Director of Passenger Car Development. He often noted that the passenger car testing and development was far more difficult than that of the racing car.

After being hired right out of college, Uhlenhaut was immediately involved in the development of the chassis of the T170, the remarkably long-lived Mercedes passenger car that featured four wheel independent suspension. As the authors relate, “He skillfully combined the conventional front axle with two transverse leaf springs with a double joint swing axle in the back…” He was constantly driving and improving on the handling of the car, which had a tendency to oversteer. While he enjoyed oversteer, he also knew that customers would probably prefer a bit of understeer. The experiences gained were directly transferred to the racing cars he would also test and develop.

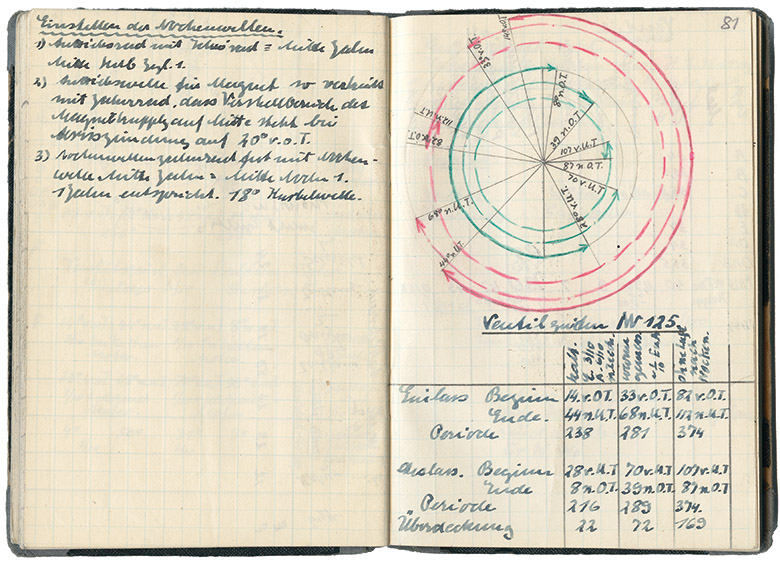

Much of his reputation was gained from the development of the W125. The authors describe Uhlenhaut’s findings and recommendations, which included: Creating an oval tubular frame and extending the wheelbase; a new double wishbone front end; the use of a De Dion type rear suspension; torsion bar springing in the rear with soft settings; increase the horsepower and finally optimize the roll center. A few pages of Uhlenhaut’s note book from 1937 are illustrated and full of details such as gear ratios, engineering diagrams and valve timing charts. His notes are still used today when maintaining the Museum’s collection of Grand Prix cars.

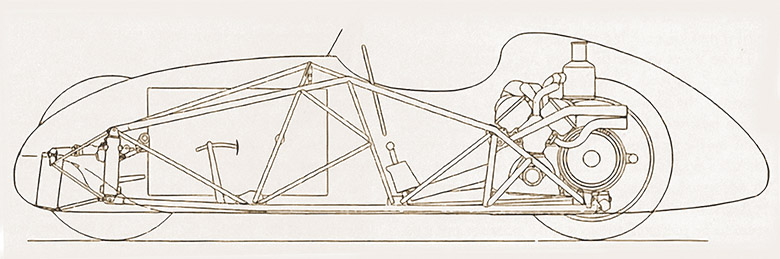

In 1947 Uhlenhaut sketched a small formula car with a 1500 cc transverse engine. It was not built but the space frame chassis was later developed for the 300SL.

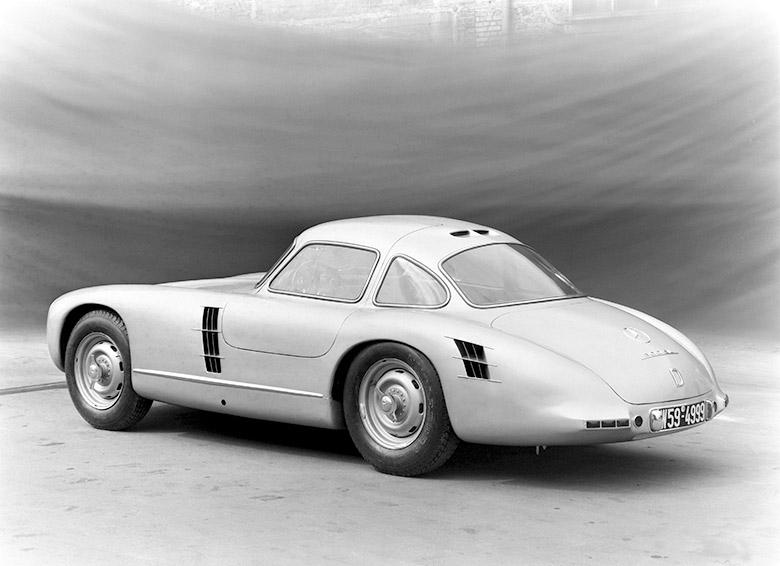

In the post war years, Uhlenhaut helped design and test the 300SL coupe and roadster; his rolling test bed was the Number 11 Mercedes coupe, a cross between the first 1952 racing coupes and the 300SLR. To call him the father of the 300SL would not be incorrect, but he usually left the detail engineering to his team.

Mercedes-Benz 300 SL Coupé Rennsport prototype (Chassis number W 194 011)) used by Uhlenhaut to develop the 300SLR and road-going 300SL.

This type of work would continue through the years on not just the racing cars, but all production vehicles. He was also responsible for creating testing equipment and methods; perhaps his most famous was the emergency avoidance test to measure the ability of a car to avoid an accident. It was standardized and still in use today.

One gets an idea of what the work must entail – Uhlenhaut himself called it a “very interesting job” – but there are few details from 41 years of engineering life; few company memos, detailed engineering drawings, specific improvements with documentation. Perhaps to do so would be rather a bore. The authors have captured the essence of Uhlenhaut, the gentleman and the engineer, but left us longing for more.

In 1965, Diana Bartley interviewed Uhlenhaut and the lengthy and revealing article was published in Esquire magazine. In Volume 45 Number 3 of Automobile Quarterly, Karl Ludvigsen published his article on Uhlenhaut, “A Life Well Lived”. Both were used as source materials by the authors of Rudolf Uhlenhaut: Engineer and Gentleman, but both articles should be read by anyone interested in the life of Uhlenhaut. What sets the book apart from the articles is a bit more in-depth information about Uhlenhaut himself, and the 296 color and black and white photos. They are superbly reproduced and very well captioned.

The book suffers from the lack of footnotes (proper documentation), and an index. Nevertheless, we can recommend this book to anyone interested in Grand Prix racing, sport car racing or just Mercedes-Benz.

______________________________________________________

An interesting related email arrived while we were writing this review. Morry Barmak sent along notice of some fine Uhlenhaut-era Mercedes-Benz art and models. I particularly liked the LO 2750 transporter which also appeared in the Uhlenhaut book. Morry can be found here:

Morry Barmak

COLLECTOR STUDIO – Fine Automotive Memorabilia

72 Scollard St.

Toronto, ON, M5R 1G2 Canada

tel/fax: 416.975.5442

“Gullwing” Morry stands next to this large photographic based artwork which makes for a very powerful & colorful image of the Mercedes 300SL to hang in your office, garage or den! It is part of a sold out exclusive edition of just 8 super glossy photos on aluminum plates. We have just one left! (36×53” / 92x135cm) – see two images below CAN$7495 / US$5625 / £4575 / €5300 + shipping.

We also received some lovely new 1/18 scale 8.5” long metal models of the 300SL coupe and roadster. Choose Strawberry Metallic or Flügeltürer Blue for the Gullwing, or White for the Roadster. CAN$265 / US$199 / £160 / €185 + shipping.

See more Mercedes offering here: http://www.collectorstudio.com/index.cfm/ID/34/SearchResults?criteria=300sl

The best track engineer …. when necessary he was faster than the official drivers : ” stop complaining about the car and show me how you can be faster than me “

Maybe this is just a legend but I like it .

For many years writers have commented on how Rudi was just as quick

as the team drivers, but only hard facts I could find were from my old pal

Denis Jenkinson who reported during session at 1954 German GP, he lapped

at 9:53, while Fangio in the marvelous new Mercedes W 196 just 3 seconds quicker

on a 14 mile course; truly impressive and five years older then Juan Fangio..

Just month later at Monza, DSJ merely reported Uhlenhaut was Very Fast !

Jenks told me he had done the same sort of trick in 1938 at Pescara on course even

longer at 16 miles ! Surprising to me was that Daimler Benz would allow their

chief engineer to put himself at risk.

Jim Sitz

G.P.Oregon

The book suffers not only from a lack of footnotes, but also from a lack of objectivity: As the authors point out numerous times, Uhlenhaut was an “unpolitical person” who “always wanted to be nothing else but an engineer”. They miss to point out that Daimler-Benz was deeply rooted in the Nazi economy, while indeed explaining that Uhlenhaut became director of a Daimer-Benz armament factory in Bohemia during the war after having joined the Motor-SS to be allowed to drive in races. After the war, he was able to escape his (justified) prosecution through the allies thanks to a British friend. To me, this is typical of an opportunist. Trivializing, yet excusing these “details” is unprofessional, if not unforgivable.

ooh the politico-philosophical things i could say…

When we visited Nuremberg our guide told us that after the Second World War, when children asked their fathers what they did in the war, there developed serious rifts in family relationships. I wonder when we’ll ever be free of the consequences some people ignored.

Can anybody out there solve motor racing mystery.?

Weeks after the debut in Mille Miglia, the 300 SL Mercedes

ran in Swiss Grand Prix

BUT, now painted in Green, Blue and Maroon.!

Odd since the factory had no plans to market the car in

production thus no reason to make them appear as

ordinary road machines for sale.

This has always nagged me. Thank you in advance

Faithfully

Jim Sitz

Uhlenhaut was one of those many talented, ambitious little Dr. Faust who were given by a human Mephisto unlimited power to achieve great feats. Ferdinand Porsche was one of them, as were Albert Speer, Ing. Messerschmitt, Werner von Braun and many others who didn’t get the chance of a second, politically cleaned-up life.

Things weren’t that different for Enzo Ferrari or Gioacchino Colombo.

Marvano’s comics serie “Grand Prix” about pre-WW II Motor racing illustrates the ambiguities of those times. Alas, a new generation of Mephistos is coming off age…