Review by Pete Vack

For being the third largest producer of automobiles in France, there is not much ‘out there’ about Simca. A fairly thorough search reveals little aside from a few softbacks covering the later 1100 series, a few repair manuals, and a couple of rather short histories in French. And some French cook named Simca competes in the same Google space.

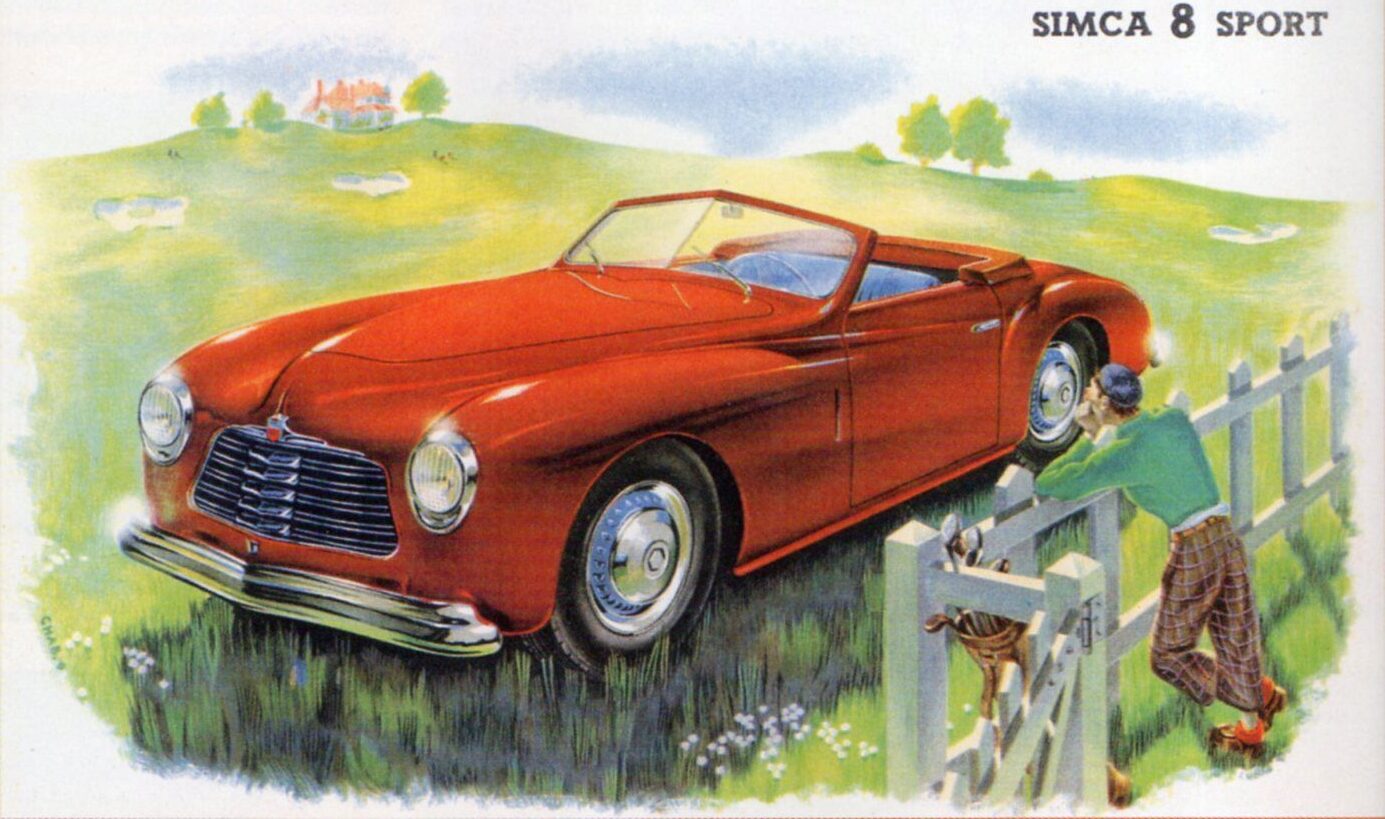

The lack of available books and articles is one reason we (ok, I) just don’t know much about Simcas. Yet we grew up in Simca’s heyday, we knew about Simca Fiats, we cheered on the Simca Gordinis, had friends who owned Arondes (yes, really!) and loved the beautiful Simca Sports convertibles and coupes of the early 50s as well as the later Bertone bodied Simca coupes of the sixties.

But I don’t know what an Ariane is, never heard of it. Or what powered the Vedette. Or what happened to the founder, Enrico Pigozzi, or why the Simca Huit was called the Simca 8. And what did Simca, who manufactured Fiats from parts imported from Italy, do during the German Occupation? And many other things this reviewer did not know are answered by the indomitable David Beare in his latest book, The Simca Story, 51 years of cars, 1933-1984.

This is David Beare’s informal, unique, often rambling books are so full of interesting details and even more, fascinating diversions, from the terrible winter in postwar Europe to the Hartnett, an ill-fated effort to produce the aluminum framed Grégoire in Australia, a post war design already rejected by Pigozzi. These asides are usually deftly woven into the fabric of the even more fascinating history of Simca, the product of one man’s vision and endeavors. He admittedly and wisely makes use of material lifted from his earlier books, and some chapters will be familiar to readers of Stinkwheel publications.

The Simca Story describes every Simca model and variation including the plethora of front engined, rear engined and front wheel drive Simca’s that complicated the Chrysler years. But Beare’s book focuses, rightly so, on the Pigozzi years, from 1933 to 1963.

Like Anthony Lago, Luigi Chinetti and Amédée Gordini, Pogozzi found himself in the Paris of the 1920s…Hemmingway’s Paris, with all the opportunity and adventure and excitement. Pigozzi was sent there by Fiat to obtain scrap metal, so necessary for the expanding production of Fiat automobiles. Soon he began importing and selling the Fiat line of cars, then obtaining completely knocked down Fiats, he assembled them and avoided the tax on imported cars. This would continue after WWII, as Simca gradually created their own cars, dependent only on the Fiat line of engines for a few more years.

Pigozzi never gave up his Italian citizenship, and had to navigate the treacherous political intrigues before, during and after WWII. After the fall of France, Pigozzi’s Fiat Simcas and Simca Fiats continued to be produced during the war years…one of the very few manufacturers to be able to do so. Most of the cars produced went to Germany. After the war, Simca somehow thrived under the PONS plan, and obtained the materials necessary to continue to produce Fiats in France. No one, it seems, was better able to circumvent French laws better than an Italian.

Pigozzi however met his match with Chrysler. In a series of corporate stock moves, Chrysler got controlling interest in Simca in 1963 after taking over the British Rootes Group earlier. The mess they made…finally selling out at a loss to PSA Peugeot in 1978…is well told by Beare, who has no kind words for Chrysler, and with good reason. When Fiat S.p.A. acquired full ownership of the Chrysler Group in early 2014, it was a delicious irony indeed.

But even then the wily Pigozzi engineered a contract with Chrysler that did not…apparently unbeknownst or misunderstood by Chrysler… include the holding company that actually owned the Simca factories and facilities. According to Beare, this enraged the board at Chrysler, who then fired Pigozzi from his position as chairman of Simca, a backfire that surely Pigozzin would have foreseen. He died, a broken man, shortly after his untimely separation from the company he had built.

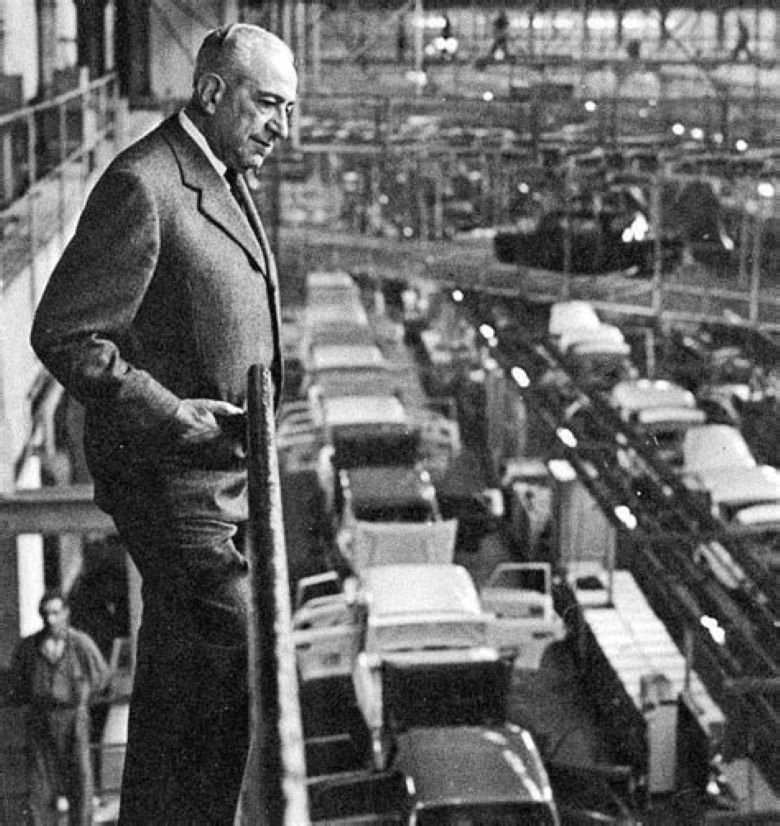

In the 1950s Pigozzi oversaw the gradual separation from Fiat, the buildup of a logical line of models using Simca designed unitary chassis, and expanding sales every year, becoming the third largest car manufacturer in France. It was quite a legacy, a remarkable effort in face of often overwhelming odds. Yet few remember his name or accomplishments.

Beare does that for us. The Simca Story is a very welcome addition to what we know and didn’t know about Simca, and a great addition to David Beare’s already impressive list of books.

Buy it here:

Order Here

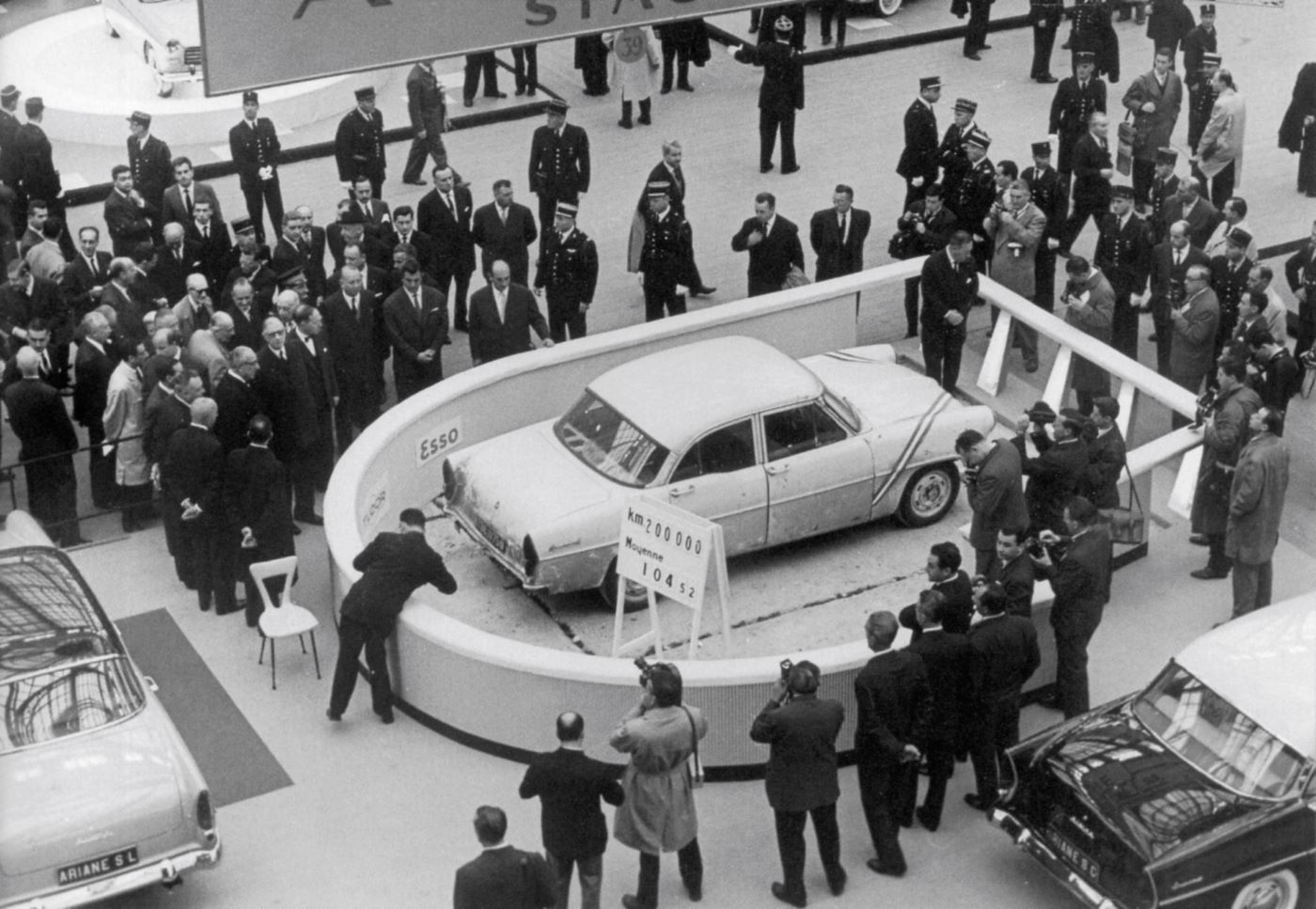

The Simca Story also includes hundreds of colorful brochures and ads, a few of them can be seen below.

Books By David Beare Reviewed by VeloceToday

The Simca Huit was called Simca 8 probably because 8 in French is huite…..

The (undisclosed?) partnership between Simca and Fiat continued well into the 60’s. Check the similarities between the “1000” Simca series and the Fiat 600-850 on the mechanical side and between the same “1000” and the Fiat 1300-1500 as regards the external shape. There’s an interesting thread in an Italian Modelling Forum. Text is in Italian, but pictures have no language…

SIMCA built pretty cars rooted in conservative technology.

For my family, the Ariane meant a huge upgrade from our tiny 4 Chevaux Renault.

SIMCA’s top range was the Beaulieu and Chambord, featuring a lot of chrome, aggressive tail fins, and a greedy front grill.

Their old Ford V8 sounded nice and rounded up the presidential status.

The same engine graced the Versailles and Trianon, smaller models still mimicking the current American design in a low-key manner.

For the baby-booming families of the early Sixties, a smart move was to install the smaller 4-cylinder engine of the compact sedan Aronde in the king-size body of the Versailles.

SIMCA called it Ariane, whose thread guided us along France’s Routes Nationales, Germany’s Autobahnen, and Italy’s autostrade.

With 62 HP SAE, the “Rush” engine with its crankshaft smoothly rotating on four bearings didn’t make a dragster out of Ariane, but it was enough to carry up to 7 passengers at a cruising speed of 120 kph, safety belts not included.

Ariane cost 9.150 Nouveaux Francs when a Jaguar E-Type was tagged at 40.000 NF and a Ferrari 250 GTE at 70.000 NF.

Like Opel’s Rekord model, Ariane symbolized an ever-improving living standard with a naive touch of showing off.

She gave way to a then futuristic and technologically advanced Citroen ID 19, a further step toward modern times!

Ariane’s “Rush” engine’s crankshaft rotated on 5, not 4 bearings!

A welcome innovation allowing higher revs with less vibrations.

Does the book cover the alliance between Carlo Abarth and Simca to create the Abarth Simca sports cars in the early 60s? This collaboration has never to my knowledge been clearly explained or demystified.

The other Simca Google is serving up is Simone “Simca” Beck who was Julia Child’s cookbook collaborator.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Simone_Beck

Another French original.

No, it was not covered in David’s book.

Pete