The Classic Twin Cam Engine

By Griffith Borgeson

Hardbound, 275 pages, black and white photographs and diagrams

Dalton Watson Fine Books Limited, Deerfield Illinois

First Edition, 1979, reprinted 2002

ISBN 0-901564-19-2

No longer in print

By Pete Vack

The case of the classic twin cam attracted the attention of automotive writer Griff Borgeson (1918 -1997) in 1949 with the publication of Laurence Pomeroy’s Grand Prix Car; Borgeson would spend the next thirty years trying to find out who was really responsible for the design of the ultimate internal combustion engine.

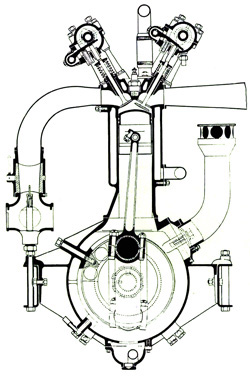

Left, the 3 liter DOHC four valve 1913 Peugeot engine.

Borgeson sought out the old, the rich, the famous and the ones who did not want to speak out in the first place.

Borgeson employed his dogged detectiveness, his skill in French and Italian, his ability to access ancient files in decrepit factories; he sought out the old, the rich, the famous and the ones who did not want to speak out in the first place. He followed the clues, tracked down every lead, gathered the documents, went back and forth to verify opinions. Over the years of chasing this elusive truth, he would become aware of the limitations of the historian, the Rashomon effect, conflicts and variations, vices and vendettas, and finally conceded that a historian, “if he works hard and creatively he can aspire to a relatively valid approximation to the question of What Really Happened.”

What was known and agreed upon regarding the origins of the DOHC engine was this:

*That from 1885–generally regarded to be the birth year of the practical automobile–it took only 27 years for the internal combustion engine to reach its zenith in the efficient, double overhead camshaft layout:

*The design not only exists to this day but has proliferated and multiplied; it is still the norm for Grand Prix cars, although valves springs have been replaced by hydraulics:

*That this specific design originated with the Peugeot Grand Prix car of 1912-13:

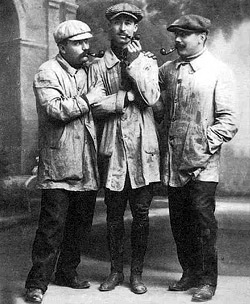

*That the people responsible included race driver Jules Goux, Italian mechanic Paolo Zuccarelli, and another French race driver and organizer, Georges Boillot. None were engineers, yet the design would require a truly gifted and well trained engineer. The threesome hired a Swiss by the name of Ernest Henry (with a y not i) to do the drawings. (The term “Charlatans” came about because the trio of race drivers/mechanic–who had the support of Robert Peugeot–had imposed themselves upon the professional engineering staff at Peugeot and were immediately labeled as imposters by the diploma-laden engineers.)

Sounds good to me, so where was the problem?

How could a team of drivers/mechanics have engineered the fantastic Peugeot engine on their own?

First, Borgeson contended that since the internal combustion engine was a truly significant force of the 20th century. The double overhead cam layout must be even more significant therefore one should ensure proper credit is given to the right people.

Second, over the years, the role of Ernest Henry had been downplayed by the hitherto expert authority W.F. Bradley to the extent that the design was attributed more to the three “Charlatans”, Goux, Boillot, and Zuccarelli, than to the Swiss engineer. “Something absolutely phenomenal happened with the GP Peugeots,” wrote Borgeson himself in 1973, as if a miracle had occurred in the offices of the factory. But there were no miracles, only three mechanics and a “draftsman”…one who merely draws out ideas, and is not an engineer.

The Charlatans. Left, Zuccarelli, Goux, Boillot.

Based on input from the doyens of motorsports history, W.F. Bradley and Pomeroy, in 1966 Griff published his seminal and highly regarded book, “The Golden Age of the American Racing Car”, which traced the evolution and origins of the Miller, Offy and other American DOHC racing engines. In that book, Borgeson gave credit to the design to the three charlatans and a draftsman, seriously degrading the Henry input, towing the line Bradley had made clear time and time again. When asked who was most responsible, Bradley had told Borgeson that Zuccarelli in particular had conceived the radical new Peugeot engine. This despite doubts from Pomeroy, who had nevertheless relied on primary-source Bradley. Unfortunately, Pomeroy died before he could be consulted by Borgeson on the subject.

Hell has no fury like a historian scorned. Shortly after the book was published, Borgeson found and interviewed Rene Thomas, who drove for Peugeot, Ballot, had won the 1914 Indy in a Delage, and knew everyone, including Henry. “The full credit for the GP Peugeots belongs to Henry, and my friend Bradley is absolutely wrong.”

Was the world-famous journalist leading him astray?

Borgeson was confused. “Following the session with Rene Thomas I was frankly angry with Bradley”, Borgeson recalled. Getting back to Bradley, Griff found that for whatever reasons, he was sticking to his guns; Henry was a mere draftsman for the brilliant ideas and concepts of Zuccarelli and friends.

At this point, Borgeson’s own credentials as a writer/historian may have been in jeopardy. Was the world- famous journalist leading him astray? Why were the two stories so different? And how could a team of drivers/mechanics have engineered the fantastic Peugeot engine on their own? In 1973, after years of more research, Borgeson published “The Charlatan Mystery” in “Automobile Quarterly”, V11-3. He brought in new material obtained from French historian Paul Yvelin, Roland Bugatti, and Henry’s son and grandson. But although close, in the end, Borgeson had to conclude that “…we must be content with ‘three mechanics and a draftsman’. These ‘imposters’ reached a certain summit. To displace them from it will take more evidence that has been put forth up to now.”

It seemed like Bradley would have the last say after all. But the publication of “The Charlatan Mystery” brought Borgeson more letters and recollections. In 1977, Borgeson took a fresh look at the Ballot, a rare French race car made immediately after WWI, which had an engine straight out of the Charlatan school of design. He had made more discoveries including a draftsman who had worked closely with Henry at Ballot by the name of Fernand Vadier, determined that Henry was most definitely responsible for the Ballot straight eight, and that the cars were really much more successful than W.F. Bradley had led a wide public to believe.

All of which led to “The Classic Twin Cam Engine”, first published in 1979, and again by Dalton Watson in 2002. A compendium of all that had gone before, often word for word, Borgeson laid out the search for Ernest Henry, and finally, although somewhat at times presumptuously, added new material to debunk the Bradley-inspired theory that the three Charlatans were the geniuses behind the Peugeots.

Ernest Henry, Rest in Peace, finally.

It is, in some respects, a strange book; the first of four parts deals with people and personalities, the chase, the discoveries, and is entitled “The Charlatan Cycle.” It covers Henry’s early training, his involvement with the Peugeots, the Ballot and Coatalen at STD (see Talbot Darracq, The Engines). Then in somewhat chronological order, Part II deals with the European School, tracking the development of the DOHC from Delage to Mercedes Benz from 1919 to 1940. Part III is briefer but deals with the American School, influenced by the Ballot, the Peugeot, and the Miller/Offy. Finally, Borgeson briefly shows us the modern post war twin cam engines used in GT and Grand Prix cars up to 1978. All parts are very well illustrated with both drawings and photographs—all in B&W but very clear.

“In his prime, Griff was one of the truly great auto historians and he forged relationships with the people responsible for important and fantastic automobiles,” said Jonathan A. Stein, an “Automobile Quarterly” editor who worked closely with Borgeson. He was also human, often controversial, never afraid to upset long standing traditions and beliefs, and there were those who complained about his reliance on primary source interviews with subjects who had failing memories, an axe to grind or a reputation to hone. In turn, Borgeson himself had become furious with historian Bradley who had his own ax to grind. Yet Borgeson would write the most touching and sincere biography of Bradley ever published (AQ V20-2). “The Classic Twin Cam Engine” was dedicated to both his wife Jasmine, and “to the memory of William F. Bradley, chronicler extraordinaire, whose role in the automotive history was more important than we shall ever know.”

The dedication could also be applied to Borgeson. “The Classic Twin Cam Engine” stands the test of time; there are no serious challenges to his work on the subject and it remains essential reading for anyone truly interested in French, Italian, Formula One cars, or in fact the cars in your driveway. It’s not an easy read despite being a great mystery story. Borgeson is no Agatha Christie nor claims to be. It skips and jumps and posits and demands the full attention of our grey matter. But it is the enchanting, human story of the internal combustion engine and the 20th century. To know it is to know our passion for the automobile.

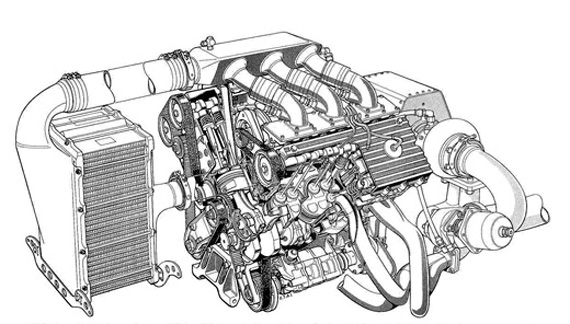

The 1978 1.5 liter turbocharged Formula One Renault V6 developed 510 hp at 10,800 rpm. Renault would take the lead in developing the system of hydraulic valve closing.

Sources

The Classic Twin Cam Engine, Borgeson 2002

The Golden Age of the American Racing Car, Borgeson, 1966

Automobile Quarterly, V11-3

Automobile Quarterly, 15-2

Automobile Quarterly, 16-2

Automobile Quarterly, 20-2

The Classic Twin Cam Engine was one of the first books I bought years ago as I undertook a more detailed understanding of the development of the automobile.

It remains one of my most important volumes, 25 years later, not only on account of the information imparted [and I agree with Pete that it is a challenge to follow] but also because it is a road map for research, inference, deduction and integrity.

The Classic Twin Cam Engine is ideal for long winter evenings, snug in front of the fireplace [with a glass of preferred libation close by, perhaps.] It is a perceptive introduction to gifted, even visionary, personalities. I cannot recommend it more highly.

Great story, and much appreciated. having the backstory makes the Twin Cam book much more understandable. I was lucky enough to spend an afternoon with Borgeson, when he was at the Milwaukee Mile. We spent the day looking at Millers, discussing early engineering, and choosing our favorites. He was fond of the 4WD postwar car..

Your points about his temperamental and passionate writing ring true. His love of Alfa Romeos and Millers shows through in all his work, and his history of Bugatti (influenced by his friendship with Jean Bugatti, I believe) reveals the emotional complexity of his work. He was also a dear friend of Vittorio Jano, and wrote on him well. We owe him a lot.