WE HAVE A WINNER! Nicolas Zart got it right. Read comments after the story.

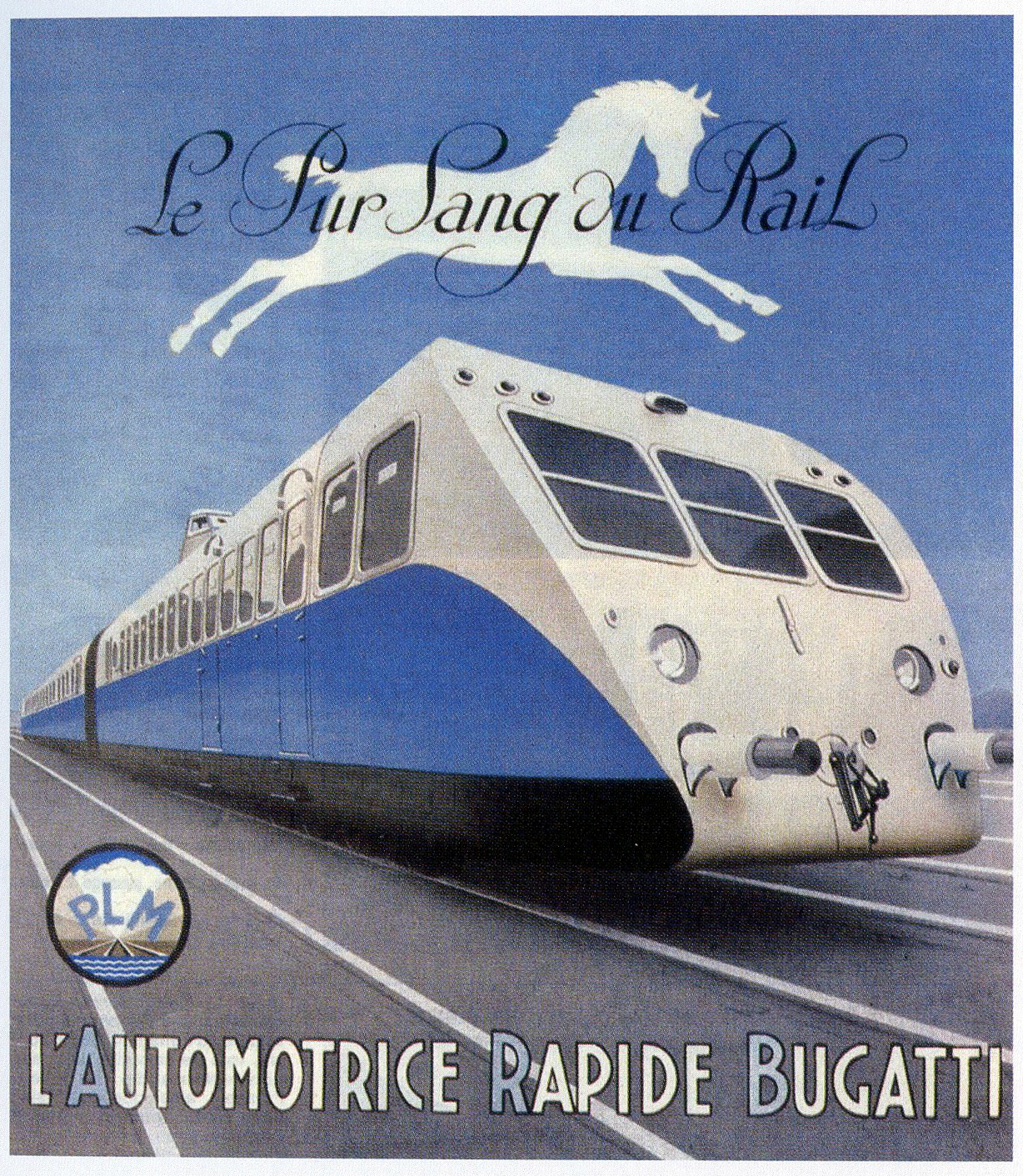

They blew it. In this ad created by Compagnie du Paris-Lyon-Mediterranée the words “Pur Sang” are separated by a space. This is incorrect of course. The first reader to tell us why gets a free year’s premium subscription to VeloceToday.

Review and discussion by Pete Vack

Eric Favre’s book “Automotrices Bugatti, Rail Thoroughbreds” spotlights Bugatti’s railcars

Winter, 1959. The latest issue of SCI was always a godsend, particularly in the dark months. We had been overjoyed to see that shortly after taking over at Sports Cars Illustrated, Editor John Christy had corralled the services of Ken Purdy, who often wrote of things Bugatti. So it was with this April issue that was before me on a March day in 1959; Ken Purdy joined up with Rene Dreyfus to come up with an article, “Knock Down the Wall, S’il Vous Plai’t,” about the Bugatti’s railcar, or automotrice. It was the first time this writer had read of such a venture.

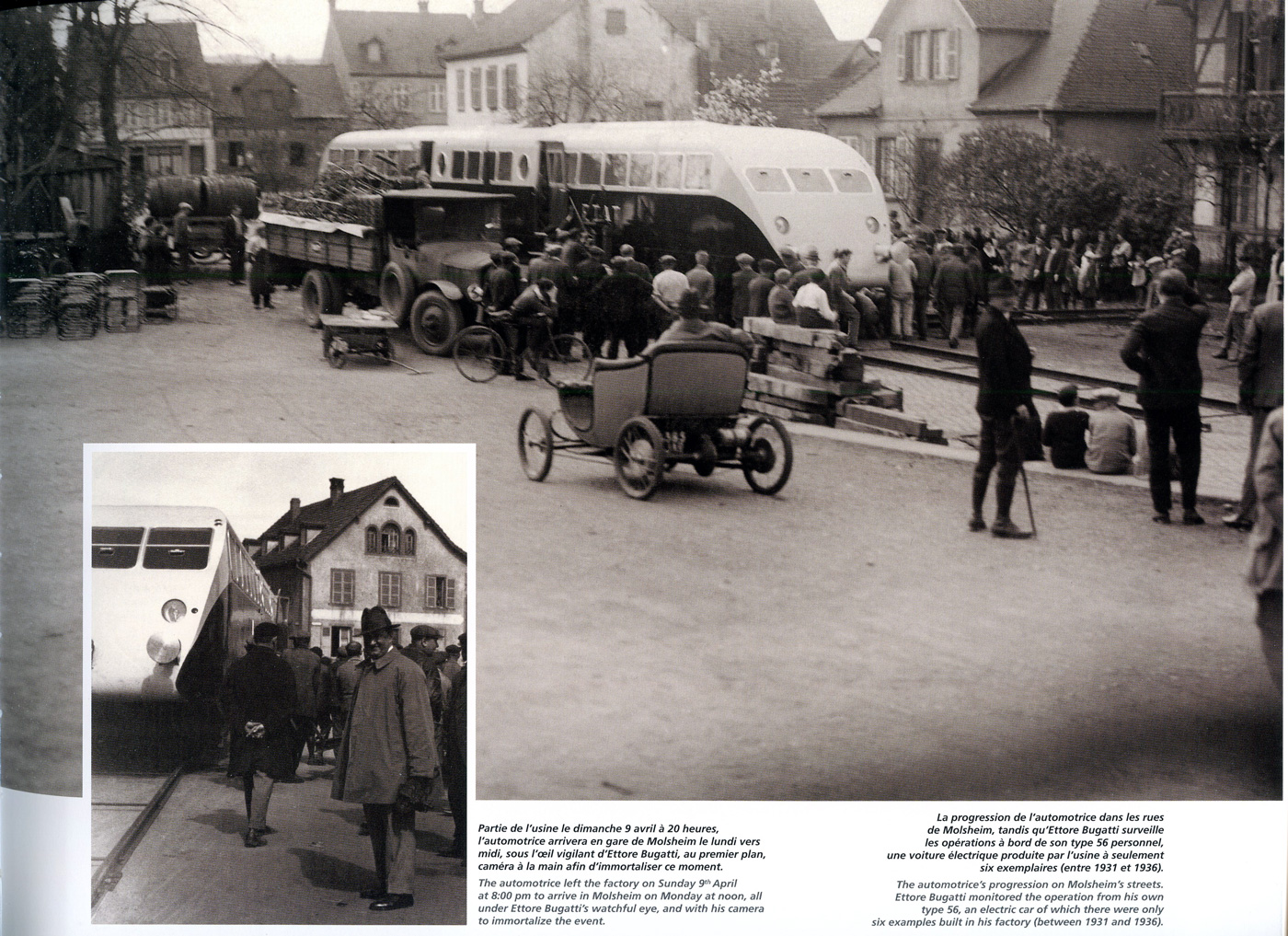

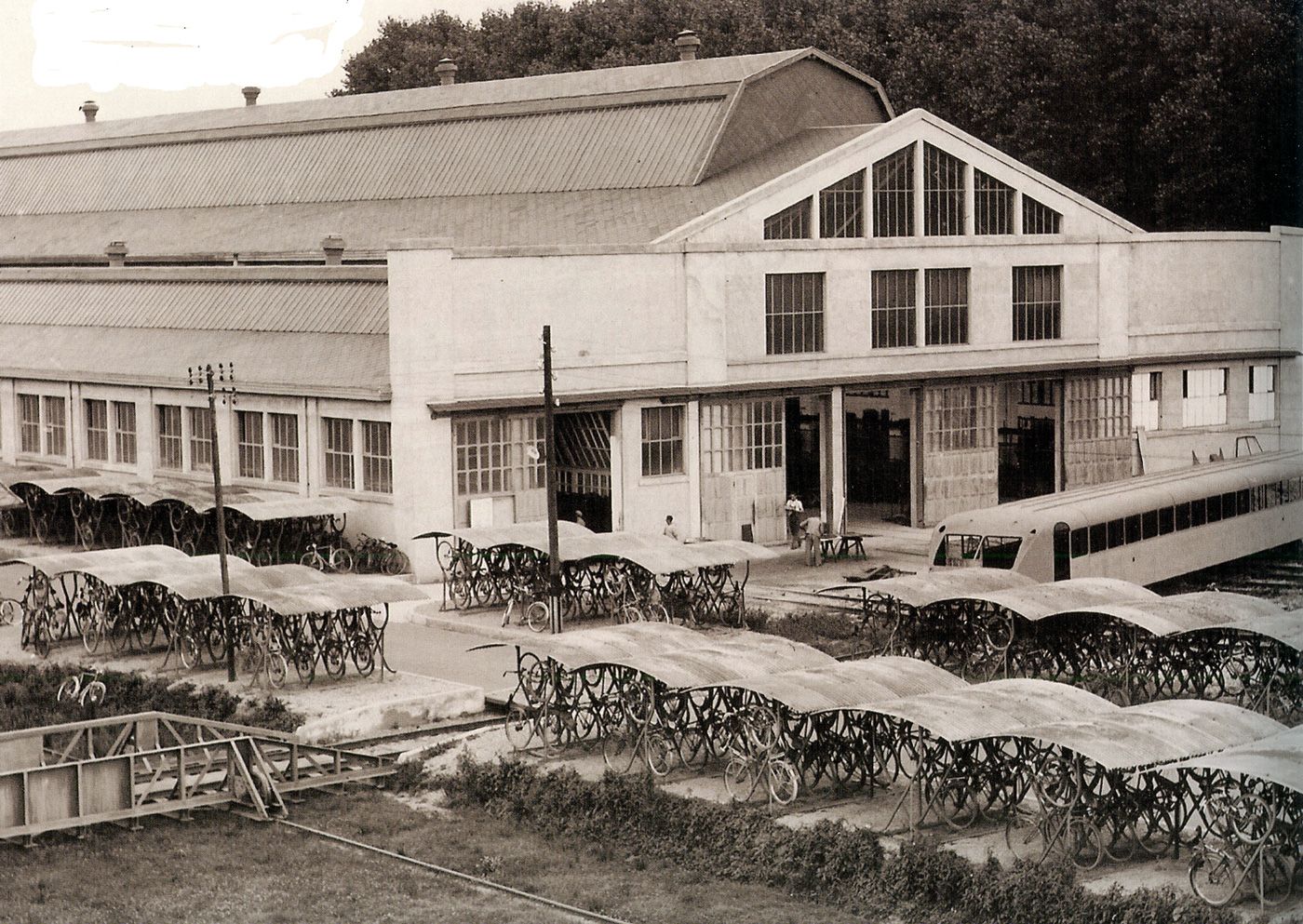

Perhaps the title, daring us to think that Ettore Bugatti had built too large a vehicle for his factory and had to knock open a wall in order to move it outside, ala Henry Ford, made the article unforgettable. And to a certain degree the title was true, but as it later stated in the article, it was only the surrounding factory wall had to be knocked down, in order for the new railcar to be taken…a few rails at a time, to the Molsheim train station.

The first automotrice built by Bugatti had to be moved by hand from the factory to the train station in Molsheim. Ettore Bugatti was there to record the event with his camera, driving his electric T 56 to supervise the move. Rails were placed under the front, the railcar was moved a few feet forward, then the rails picked up from the rear and placed once again at the front. Photo from the book.

A dearth of information

However, while we took note of the Bugatti railcar, it was shelved as a footnote, because in 1959 most of us had a lot to learn about the road cars of Bugatti, which naturally was more important. The magazines and book publishers too, did little to enhance our knowledge of the Bugatti railcar. Of course the British, with their penchant for trainspotting, wrote of the railcar via Bugantics, which published an article, “Les automotrices” by GOP Eaton in the spring of 1961. But issues of Bugantics were few and far between. The Bugatti automotrice faded into obscurity until Eric Favre published his most impressive work which covers every aspect of Bugatti’s railcar adventure.

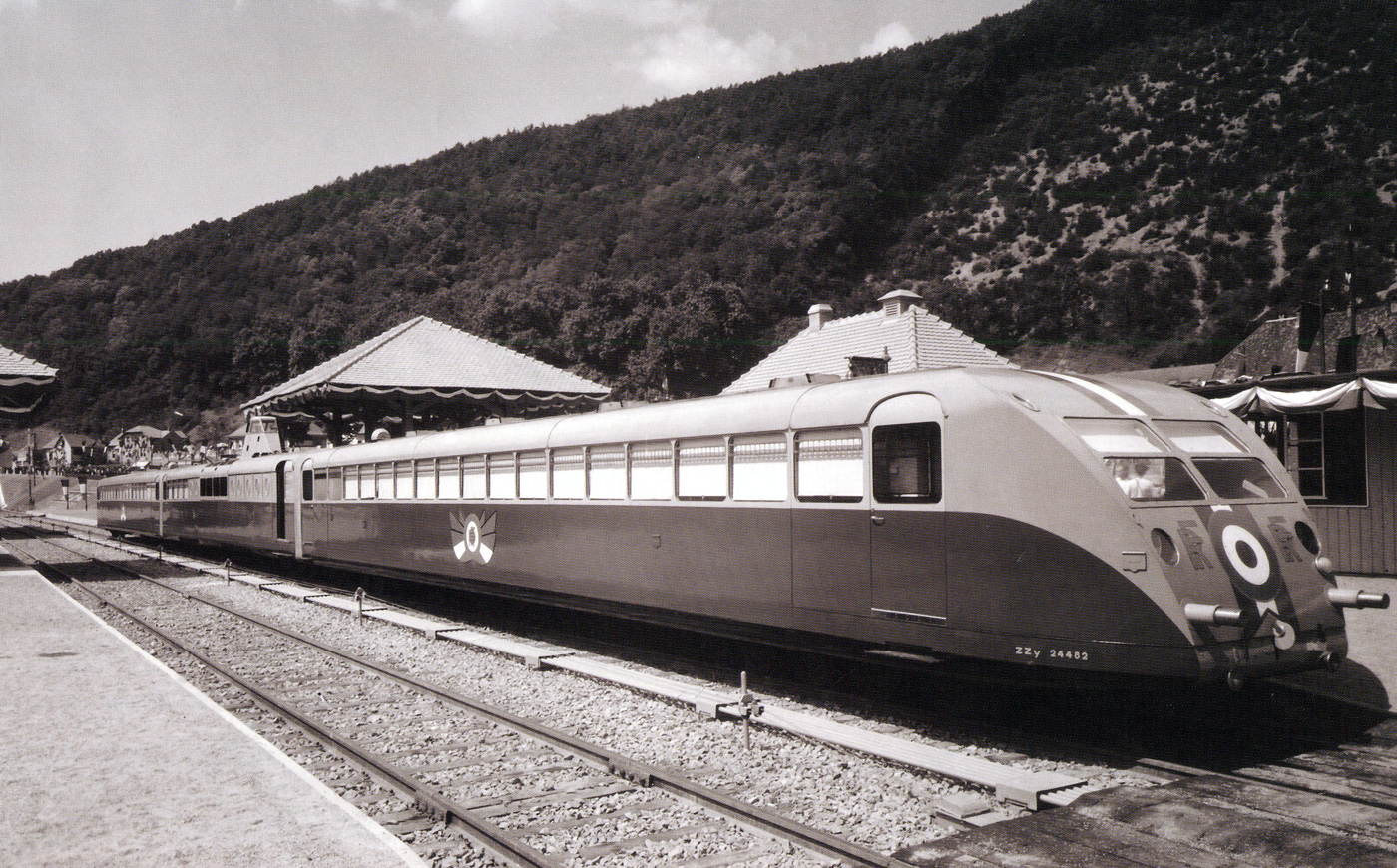

This is the WR 800 (hp) “Presidential” triple in 1937, decorated to transport the President of France from Paris to Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines. Note the height of the cupola.

Then, suddenly, too much!

With the publication of Automotrices Bugatti, we have almost more information than we can process. Author Eric Favre explains everything in detail, from the history of railcars in France, to the organizations that ran the railroads, to Bugatti’s decision to join the ranks of automotrice constructors with Renault, de Dion, Berliet, Michelin, de Dietrich, Delaunay, and later, Hispano Suiza. He explains the different models, many made uniquely for the particular contractor, what they cost, the dimensions, specs, and differences between a WR 800 Presidentiel to a WLG ‘court.’ And did you know that Bugatti designed and built an overhead cam, eight cylinder steam engine as an alternative to the gas eating Royale engines? Eric Favre devotes an entire chapter to the failed attempt. Then, and perhaps the most interesting part of the book, is a long chapter on the mechanics of the automotrices entitled “Inspired by the Automobile”.

Sandy Leith of the American Bugatti Club recalls, “I have an original of this T57 Galibier and Railcar poster here in my house in Chatham on Cape Cod. It was presented to my father (and the whole family!) upon our visit to the Bugatti Factory in 1963. I remember hearing the story that these posters were so plentiful at the Factory that they were frequently used to wrap spare parts when they were sent to customers!”

The Basics

Bugatti’s railcars, referred to as automotrices, were built in two basic versions, one with four 200 hp, straight eight, 12.7 liter SOHC engines and called the WR (Wagon Rapide), and a second model with only two engines, dubbed the WLG (Wagon Léger, or light wagon). Both had many variations as the demand for more seating space meant more cars or units needed to be added to the automotrice. With the twin engine WLG series, ‘modules’ could be added to the basic engine, which was always in the center of the ‘train’. Eric Favre tallied up 69 WLGs and 19 WRs, for a total of 88 automotrices, constructed from 1933 to 1939.

Powered by only 2 Royale engines, the WLG were less powerful than the four engined WGs, but their lightweight design still enabled them to reach 150 kph. Note the shorter cupola.

A unique feature of the Bugatti automotrices was the cupola, always placed in the center as the automotrices could be reversed and run in the other direction, without the need for a railroad turntable to get it pointed in the right direction after a run. But as the lengths increased to accommodate more passengers, the copulas had to grow higher in order for the engineer or driver to see in front of the entire automotrice.

The railcar concept worked well only if they were fast, as fast as the automobile or trucks now competing with the train networks. And to that extent, Bugatti was good out of the box, immediately able to hit 180 kph (111.8 mph) with the 800 hp WR. It was designed to serve first class passengers who could appreciate the time savings between major cities as well as the upper-class panache of the Bugatti name.

As such, the Bugatti automotrices were faster than their competition, and accordingly, more expensive. And they ran on a special fuel, consuming it at an alarming rate, while the diesel powered competitors were more frugal. But business was good, and in fact saved the automotive side of the company from bankruptcy; the company continued to produce the T57 through 1939. From a car enthusiast’s perspective, this alone makes the automotrice adventure well worth a closer look.

A closer look indeed

Bugatti’s railcars were as unique as Bugatti’s automobiles, and they bristled with often unconventional feats of engineering. Eric Favre takes us through the many features in full detail, complete with patent drawings, photos and, in most cases, clear explanations (the text is in both French and English and yet the layout and text are very well done).

In reading the book, we were eager to get answers to a few burning questions:

*Drive train and layout. How were the four engines placed in the chassis, and what was the method of transmitting the power to the ‘bogies’?

*What made Bugatti’s eight wheel four axle bogies special?

*How did the cable operated brakes operate? (Anyone who has ever had keep cable brakes adjusted on a vintage car is likely shaking his head.)

*What kind of transmissions were used? (The Royale engines were simply automobile engines with a limited torque curve.)

*How were four engines and transmissions synchronized? (All multiple auto engine attempts were stymied by the difficulties in linking the controls, so how did they control four engines simultaneously?)

*What were the details of the rubber insulated wheels? (The rail wheels were presumably totally insulated from their hubs. How did this work out, with the brakes being a part of the wheel as well? Better, we hope than the average rubber engine mount.)

*Were Dreyfus, Purdy, Kimes, and Borgeson wrong about those left-over Royale engines?

*How many survived and where are they today?

Next week in Part 2, Eric Favre’s book and plentiful diagrams will help answer these questions. Don’t miss it!

Yes, we recommend the book! Here’s how to order:

Automotrices Bugatti, “Les Pursang” du rail”by Eric Favre

Self published, 336 pages, over 400 illustrations, slipcase

U.S. customers, order direct from Donald Toms, don@bugattibooks.com, 941-727-8667, Florida $165 Post Paid

All others: Price: €99,90 plus shipping costs €8,00 for France (Mondial Relay) and Europe, and €12,00 for the rest of the world.

For further information and to order: favreric@aol.com

Great story! I am looking forward to the second Part!

Because thoroughbred is one word?

The problem with the automotrice rail car art is at the top right of the engine car there are three red signal lights and on the top left there are just two red signal lights.

The Bugatti Railcar has one too many lights on it. There should be only two lights on each side at the top. Not three and two.

After doing a little more research and just “poking around” I found more reference’s to the three and two lighting scheme. So as Roseanne Roseannadanna used to say, “Never mind.”

“Pur-Sang” is correct.

Le pur sang would mean the pure blood.

Thoroughbred is written in French pur-sang.

French language can be so tricky!

Pur sang, or pur-sang, and hat tip Ettore Pursang are perfect for this article.

I’m French, so “pur sang” means pure blood. However, it should be hyphenated. BUT, Ettore being the equestrian enthusiast, Pursang is a horse show he would have loved.

By the way, rail is also one of my passion, particularly that era and the following TEE period. The autocar period was important in many ways. It launched afterward the Trans Europe Express (TEE) lines. These automotrices were important to France. They started linking smaller cities to bigger ones. The Michelines from all the various French railroad companies were being developed and were well adapted to bring people together and connecting cities. They ran mostly on secondary tracks and crisscrossed France whereas the steam 231 and others would haul passengers on the mains lines, arteres, as they were called.

Buggati’s genius was to provide his gasoline engines for a fast and light automotrice. If I recall correctly, they had a gearbox and clutch, unlike the Michelines that ran with visco-couplers and eventually diesel engines to electric motors in the boggies. But see what Michelin did. Make those automotrices ride on tires. The ride was smooth although the total payload on the boggy was limited.

By the way, can anyone recognize what part of France is the automotrice in the sixth graphics? It looks like the South of France but I can’t tell where.

Wrong color.. I visited the Cite du Train in Mulhouse just after visiting the fabulous Cite de l’Automobile in Sept. 2019 . The Bugatti Autorail Rapide ‘Etat’ there was trimmed in red. Pur-sang as stated above needs a hyphen.

The reason why the Automotirce had three lights were because they could be called to ride on foreign networks where they needed am extra light on top of the cab. That’s why the Alsthom CC41000 and BB67000 series had these lights. They were called to travel on those network requiring a different lighting system than the French had.

The horse hasn’t got wings!

Nick, you are correct in that the word ‘pur sang’ in Bugatti vernacular (he registered the word in both France and Germany) would be ‘pursang’ without a space or hyphen. Congratulations!

So how many survive today, ad where are they ?