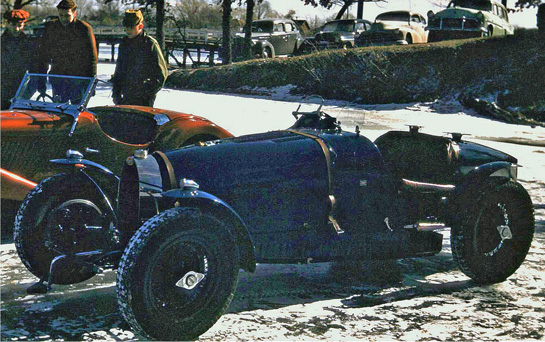

Del Lee in the Bugatti at Lake Orion Michigan. Note the leather strap holding the crank. Photo by Harold Lance

Imagine, if you will, the prototype Bugatti T35 on an ice-covered lake in Michigan. Eric Davison tells the true story of Ettore’s first T35.

There is no doubt in my mind that I grew up in the most fortunate of circumstances. While my family was not wealthy we were comfortable. We had a nice house, three square meals a day and loving parents. What made my circumstances so fortunate was the fact that my dad was an absolute gear head. He loved great cars and he dragged me along on his wonderful adventures into the world of sports cars. He had been born in England and his preference was for English sports cars but all great cars were covered by his enthusiasm. Detroit, Michigan was where he found work as a commercial artist, painting cars and trucks for ads for ads and catalogs for the Big Three.

While “Detroit” was a word that was instantly recognized by most as a euphemism for big, strong and chrome plated automobiles, it was also the home of a small cult of serious car worshippers who by 1948 had banded together to form the Detroit Region of the Sports Car Club of America

Among those early revolutionaries was Harold Lance, a car enthusiast, original Detroit Region of the SCCA member and a Bugatti fanatic. In those days, the early 1950s, you could count on your fingers and toes, the sports cars to be found in Detroit. There were few Bugattis except the beautiful Royale that was owned by Charles Chayne, then the chief engineer of Buick. There was also a Type 37 that had been the property of Edsel Ford. That car was on display in the Henry Ford Museum in Greenfield Village on the Ford property in Dearborn, Michigan.

While Lance was a young army veteran who was just starting a family and could not afford a Bugatti, he had a subscription to the English Motorsport Magazine and spent considerable time scouring the classified ads.

One day, in the June 1951 edition of Motorsport, he found an ad for what was declared to be a Type 37A Bugatti. This particular car had been fitted with a supercharged Brescia engine and the price was only 400 pounds sterling or around $1600.

The ad was so appealing and the price so low (an MG TC had a list price of about $1800) that Harold brought the ad to the attention of Del Lee. Lee, like Lance, was a dedicated car nut. He was an ex-Marine and he looked the part; erect posture, steely brush cut and a hawk-like nose. He was also the owner of a J2 Cadillac Allard that may have been the most beautiful Allard ever. It had Brooklands wind screens, wire wheels with the side mounted spare covered in tailored canvas. It was a knock out and Del Lee was a serious car lover.

But when Lance took the ad to him, Lee knew that he needed to have the Bugatti. It would represent not only a famous racing name and a first for the Detroit Region but he felt that it had unlimited resale value. He bought it but he had to dispose of his beautiful J2 to swing the deal. The first thing he did was to repaint the car. As sold it was red but, as anyone knows, racing Bugattis were blue.

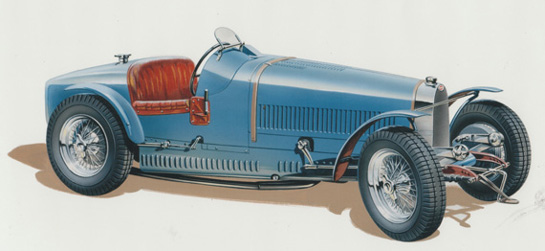

My Dad, ever the artist, painted a picture of Lee’s Bugatti for me for Christmas in 1953. Del Lee really wanted that painting and went so far as to offer my Dad a car to give to me instead of the painting. Any car that I might have been given would be long gone. The painting remains a prized family treasure and hangs on the wall of one of my son’s home.

In those days in Detroit there were few opportunities to compete. Competitions were limited to time trials and rallies. Although the Detroit Region did present a proposal to the city council of Detroit for a race on Belle Isle they were turned down cold.

An early opportunity that Del Lee had to enter his car in competition was in a time trial on the ice at Lake Orion, Michigan. While Lake Orion is now the home of a major GM assembly plant, at that time it was a small backwater resort community about 40 miles from Detroit.

The time trial was scheduled for February. The appointed day arrived and Del Lee and his son bundled themselves in sweaters, jackets, scarves and caps and drove the car those forty miles in the open cockpit Bugatti. That day that must have been close to 15 degrees Fahrenheit. It was an act of supreme automobile enthusiasm. Anyone from that part of the world would understand when I said that it was the kind of weather that chilled the marrow of your bones and made your chin numb. The ice was wind-swept and black glare. Not a fit place for anyone, let alone an open sports cars.

The time trial was to be run, one car at a time around a half mile course on the ice. The start was to be the Le Mans type, in which the driver was stationed about 30 feet from the car. At the starter’s signal, the driver would run to his car, climb in, start the engine and head off around the course. Fastest time would win top honors. Horsepower was not necessarily a desirable asset.

The problem for Del Lee and his Bugatti was that the Bug was brought to life with a crank. The solution was easy but awkward. The hand throttle on the steering wheel was pre advanced and the manual spark control was also put in the starting position. The crank was loosed from the leather strap that held it into position. All Lee had to do was run to the car, spin the crank, vault into the cockpit and off he would go.

The car was in position, the controls set and the starter dropped the flag. Del Lee ran to the car, spun the crank and the little Brescia engine roared to life. Then, as Lee tried to move to the cockpit, he slipped on that treacherous glare ice. It was a comic presentation; his body in almost slow motion with his legs flailing as he tried to regain his footing.

Before he could recover, the engine roared past the red line and exploded with a very expensive noise.

There was not much to be done. The car was trailered back to Detroit and Lee began an exhaustive search for a way to get the car back on the road. A Bugatti Brescia engine is as rare now as it was then and the options for repairing the car were limited to very expensive ones.

It became overwhelming and Del Lee sold the car, broken engine and all to a gentleman in northern Michigan where it sat until it was purchased by a man in Grand Rapids, Michigan who managed to get the car back on the road by installing an MG engine.

A Bugatti with an MG engine is about as worthless as a Bugatti can be and the Grand Rapids owner let it sit and gather dust while he hoped for suitable buyer.

I never did think much more about the car. It was just a funny memory about the fate of an old Bugatti. I had the paining on my wall as a reminder of the Bugatti exploding while a frantic Del Lee slipped and slid almost like a cartoon figure in slow motion towards the cockpit.

In the mid 80s I met Hank Haga. Those familiar with GM lore will remember Hank as a true super star on the design staff, one of those rare GM people who really knew and loved cars. Among great automobiles that he owned along the way were a 250 LM Ferrari and a Ferrari 166 Barchetta. His wife, Ellie, an artist as equally talented as Hank, used a 512 Boxer Berlinetta as her daily driver.

Rather than saving his annual GM bonus, he would buy cars and a Bugatti had long been on his wish list. He learned that there was a strange Bugatti sitting in a barn in Michigan. He searched it out and eventually became the owner of this derelict for the sum of $3600.

Among Haga’s GM duties was that of resurrecting the dull and drab Opel division and from 1974 to 1980 Hank and Ellie lived in Germany while Hank worked his magic on Opel, turning an almost moribund builder of really dull cars into a company that could compete with the best of Europe.

What are the odds of seeing both the prototype Bugatti T35 and the prototype Squire (then owned by Charlie Davison) at a lake in the middle of Michigan? Photo by Harold Lance.

While in Europe, the Hagas approached English Bugatti specialist Hugh Conway about the Bugatti restoration project. Conway’s research turned up some unusual facts. The car was not a Type 37 A Bugatti at all. It was, in fact the prototype Type 35, serial number 4323 and that Ettore Bugatti himself personally driven the car to the 1924 European Grand Prix at Lyon, France where it was utilized as a factory backup car.

The differences between a Type 37 and a Type 35 are enormous and there are no records as to why or how the car was originally converted. The Del Lee Type 37 had wire wheels and a four cylinder Brescia engine and the Type 35 had the beautiful cast aluminum wheels and a straight-eight engine

In any event, a suitable engine was found and the car returned to its original state. To say the least, it was (and is) magnificent.

In 1980 Hank returned to GM in the US and was eventually put in charge of the GM West Coast studio in Thousand Oaks, California where his team worked on creating advanced designs for all of GM.

The Bugatti began to be properly exercised. Hank and Ellie used it for touring through the hills and valleys of the area sometimes with a picnic basket crammed into the cockpit. It is hard to imagine a more suitable place than the canyons of Malibu for Bugatti-ing. Hank soon became a regular competitor in vintage races.

By the mid-eighties I had met Hank while doing advertising for Chevrolet in California. We were both car lovers and I soon discovered that he was the owner of a Type 35 Bugatti.

My partners and I conceived an advertising campaign aimed at making Chevrolet a more socially acceptable automobile in import conscious California. The idea was that no matter how incredible and sophisticated your automotive tastes, there was always a need for a Chevy in your life; a car for the regular chores of everyday life. We were to place Chevys in garages along with highly recognizable classics and photograph them for magazine ads.

I immediately thought of Hank Haga and his Bugatti. I arranged a time with Hank, set up a photographer and proceeded with the shoot which entailed having a Chevy next to his Bugatti in his garage. When all was done, Hank, Ellie and I sat around his kitchen table having a glass of wine and talking cars. The inevitable question arose.

I asked Hank where he found the Bugatti.

“I bought it from a guy in northern Michigan and it had an MG engine in it.”

Boy, did I have a tale or two for him.

Ellie Haga still has the Bugatti and her son has replaced Hank as the driver in vintage events.

Sandy Leith, Bugatti owner and vintage racer informed me that the damaged Brescia engine (#708 from car 2302) had been given to him in March of 1992 by fellow enthusiast Tom Rosenberger. In turn Leith passed it on to Peter Charlap who found a welder who was an artist and the badly damaged crank case was repaired and the little Brescia engine is now back on the track.

Bugattis somehow have a way of connecting themselves with interesting people.

VERY COOL !!!!!! Is that the Squire Dr Simione now owns ?

Big thanks to Eric for another wonderful story about the adventures of Charlie Davison and Harold Lance. Eric’s stories and Harold’s photos continue to provide a nostalgic glimpse into the early sports car world in Detroit.

Thanks for the memories…

What an interesting story, I knew Henry Haga and still have contact with Elly but I did not know all these interesting details. Thank you very much.

There was always an extra mystique attached to a Bugatti that ensured, even in the fifties and sixties when other contemporaries were ‘just old cars’, there was a small but devoted cognoscenti who were ready to accept the challenge. And a challenge it must have been, it would have been easy enough to buy and race a cheap sports car, but just as easy to do priceless damage to such a complex motor. There were many thoroughbreds fitted with more mundane motors during that time, that had to wait for the market to boom before it would be worth anyone’s while to restore them as original. There is a Bugatti 35 still competing regualarly here in Australia with a 1500cc Anzani which has a continuous history.

On another note, we should all be grateful for the research done by the late Conway that has helped identify so many cars and parts and unravelled mysteries, without which it is doubtful so many cars would have survived and been reunited with losts parts.

Wonderful story!

Yes,

A great story. Hank and Ellie were wonderful people, both very talented artistically. Hank was one of the best. I worked for him for three years and can attest to his “car guy enthusiasm and genuine love for cars. I think it took twenty three years to restore the car, Ellie sewed the leather seats and with extra leather made period leather jackets for both of them. Maybe caps too.

Hank and Ellie had a party once, we made gnocchi and meatballs for a lot of people. Zora Arkus Duntov was there and so was the Bugatti. He was explaining to Hank how the engine torque tether worked. I looked over to him and could see that he already knew, but he let Zora go on and on for the rest of us. There were many great car people at Design in those days and there still are, Hank was not the only one but he was one of the most gracious and enthusiastic.

DICK RUZZIN