Review by Pete Vack

Photos from the book courtesy Haynes Publishing

Not what you think, but maybe better

Just heard about a new Haynes repair manual – for the Bugatti Type 35! Finally, now I’ll be able to properly adjust those three valves through the little holes in the cam cover, get a handle on the operation of the multiplate clutch and those clutch actuation levers, set up the magneto correctly and even do an alignment! I could hardly wait to get my copy…

And, when it arrived, did it have all the same information as, let’s say, my Alfa manual? Were there detailed step-by-step instructions on how to tune the carbs and remove the transmission? Were there photos and factory drawings and parts diagrams?

Well, yes and no.

Reasonably, (but reason often is absent when discussing Bugattis) one might not really think that a Bugatti workshop manual would offer the same type of information as a similar manual on a Honda, Porsche or Alfa; a rather farfetched idea. So what then is between the covers?

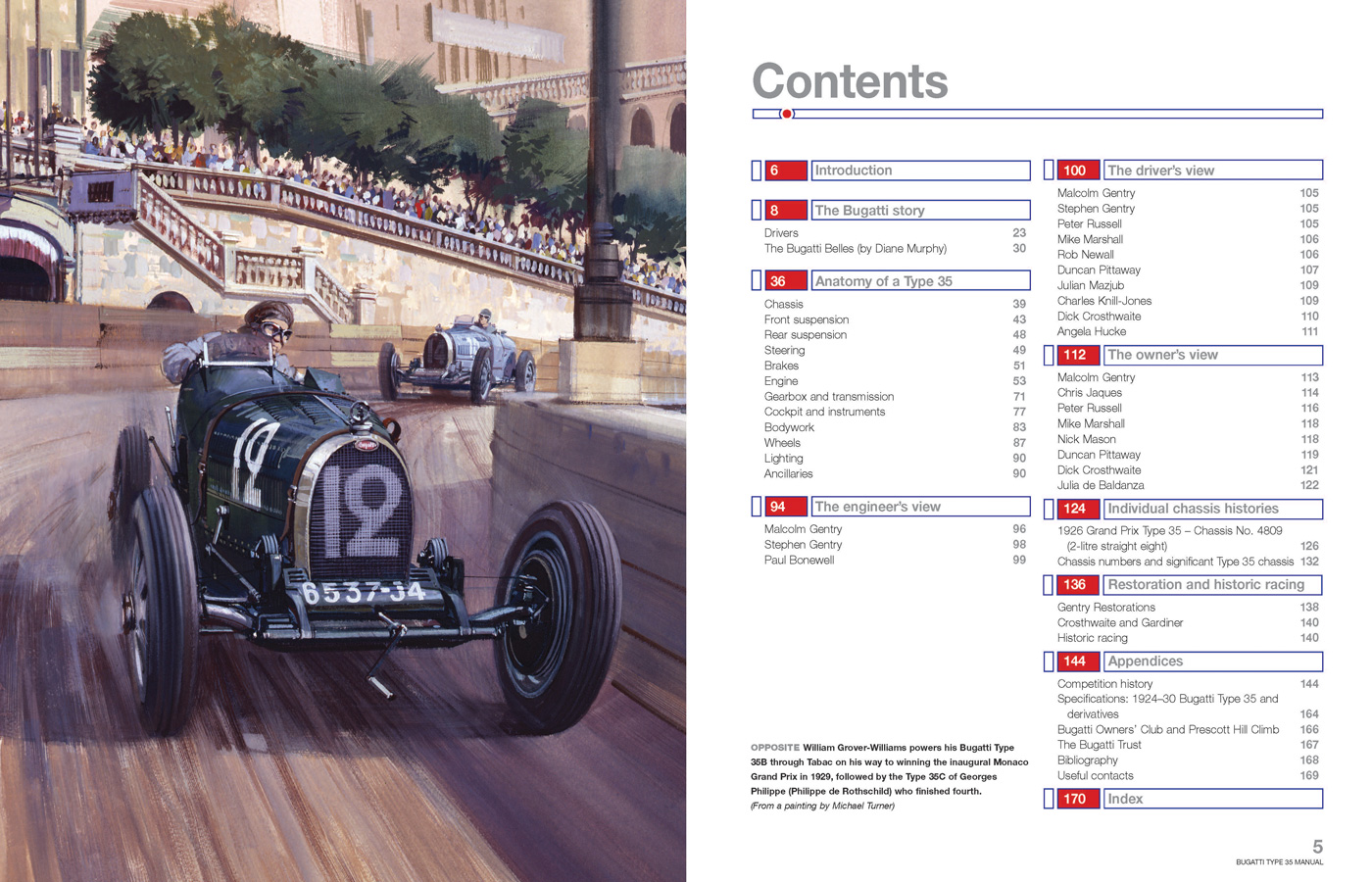

First, this workshop manual is hardbound, with 172 glossy pages, and when first opened one is greeted by a beautiful Michael Turner painting of Williams in his Bugatti T35B winning the inaugural Monaco Grand Prix in 1929. This serves as a deterrent to taking it out to the garage and getting greasy finger prints on the book.

Right off the mark one can see that this is no pulp paged repair manual. The superb Turner painting jumps out of the page.

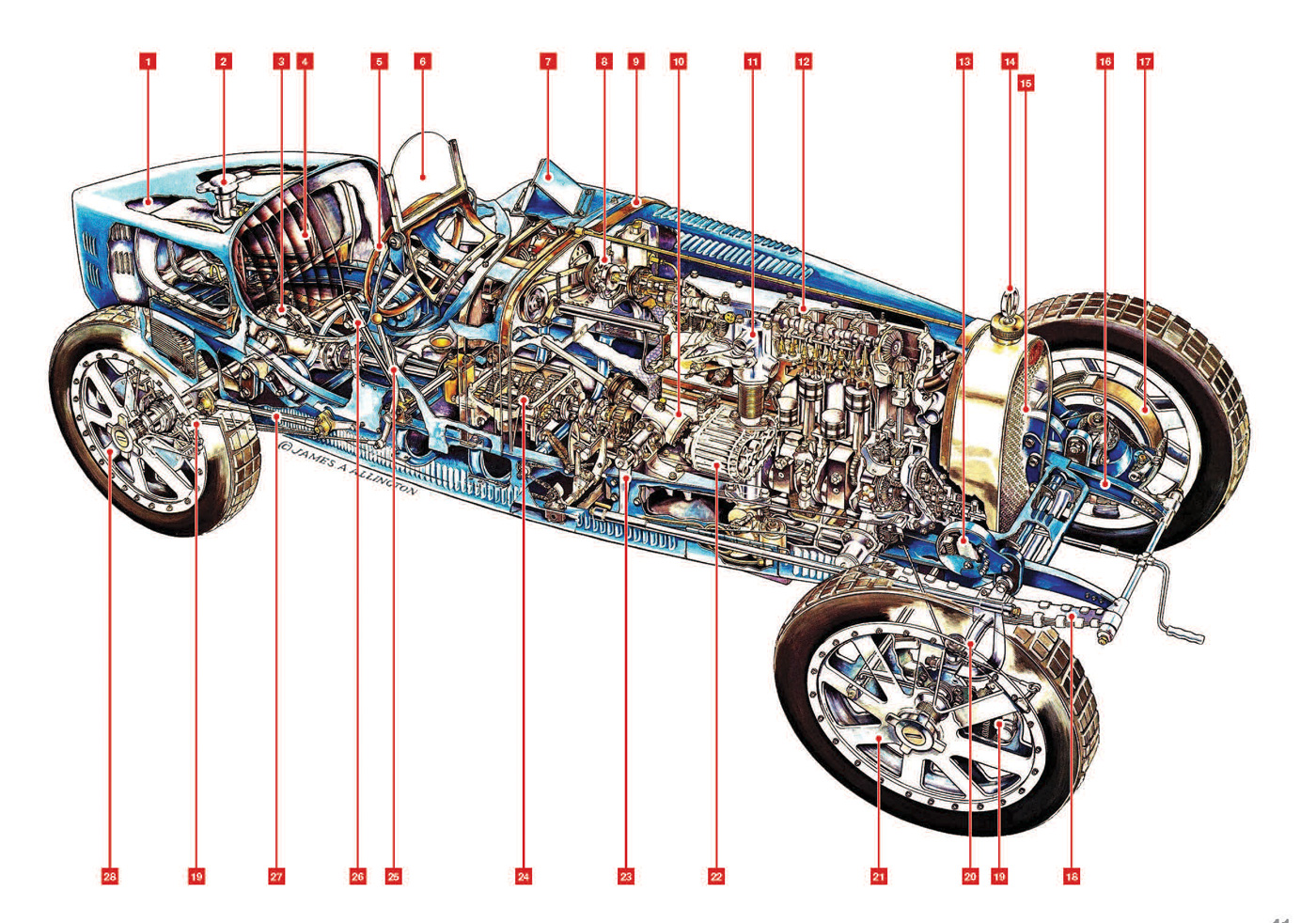

Not a real instruction manual, the heart of the book is a section entitled “Anatomy of a Type 35” and it reveals the technical aspects of the T35 in some depth. The author, Chas Parker, obtained the full cooperation of two Bugatti restoration services, Crosthwaite and Gardiner, and Malcolm and Stephen Gentry, as well as spending a good amount of time at the Bugatti Trust at Prescott. The Trust also provided a great many informative engineering drawings of the Bugatti, and excellent color photos of every part of a Bugatti from the engine to the ancillaries, and describes the operation of each. It may not tell one how to fix or replace it, but the technical detail is interesting, a mechanical guide for those who don’t want to get their hands dirty, or more likely don’t own a Type 35, never have and never will, like this reviewer.

Bugatti restoration articles are abundant in books and magazines, but here, Parker quotes the Bugatti gurus as each mechanical bit is described. For example, the makeup, operation and shortcomings of the shock absorbers are explained; they tell us why the front springs are so important to braking and handling; and did you ever wonder why the coachwork is held to the chassis with special, wired body bolts? Well, I never knew but I do now. The many such insights make the reading worthwhile.

This is all to the good, but often leads to more questions. This is not a criticism; the point is, the book raises questions for each one it answers. And that is the fun of it, for I really got into it, enjoying the more-in-depth searches my curiosity made imperative.

Diagrams and photos of the clutch operation caught my interest. It is a wet clutch — wet meaning the use of paraffin and oil to keep the multiple discs from frying (today the modern clutch disc materials used makes this unnecessary) and is activated by an intricate set of levers. According to the book, the levers keep the discs pressed together but they are also aided by centrifugal force. But what has centrifugal force got to do with the levers I wondered? I went to Google and after looking at a YouTube clip of a similar T37 clutch in operation it eventually dawned on me. Now it’s your turn.

T35 Variants are also included in the scope of the book. Here, a T37 cockpit, note the flywheel and clutch. No magneto showing in the dash of the T37, so prominent in the T35.

Similarly, the complex roller bearing eight-piece crankshaft is photographed and described, but not the actual fitting, and getting each throw exactly right. I failed to find any photos of a Bugatti crankshaft actually being assembled and there were none on the Internet either. Do the individual crank parts have serrations? In the book, Parker quotes engine guy Paul Bonewell, “It’s cottered together…you just have to be aware of how it goes together”. Cotters, huh. Like on a bicycle pedal crank? More searching. Wiki: A cotter is a pin or wedge passing through a hole to fix parts tightly together. Typical applications are in fixing a crank to its crankshaft, as in a bicycle, or a piston rod to a crosshead, as in a steam engine. Bonewell again, “You have to make sure the cotters are good and hard, otherwise they will clearly move…and there’s only one or two people in the country [who] can do that.” Maybe that’s the reason it’s difficult to find photos.

Also interesting and relevant are three sections devoted to looking at the T35 from an engineer’s standpoint, from a driver’s view, and from that of the owners. This is enlightening. The comments from Dick Crosthwaite give us an insider’s view of the design while Malcolm Gentry explains how Bugatti made his own nuts and bolts, none the standard sizes – they tell us why this was done. Ettore comes off not as so much as artist but a realistic, thoughtful designer who used the construction techniques and materials of his day to the best advantage.

An ex-Raymond Mays Bugatti T35, now owned by Chris Jaques, is the subject of a owner’s view, chassis history and vintage racing segment.

Parker talks to ten different men and women who actively race the T35 in vintage events, providing a comprehensive feel for what it is like to drive a Bugatti. He also talks to eight different owners who again provide detailed information about day to day driving and maintenance. This adds to our understanding because there are many different experiences. In general, they all agree that the T35 is a most remarkable machine and most think that the early cars – the unblown 2.0 and 2.3 liter cars – are the best. And they say that one will not be able to get the feel of the car just by driving it on the street, however fast. Like Ferraris, the T35 has to be driven at racing speeds, hurtled through the corners at the limit before it comes into its own.

The book also includes sections about the history of Bugatti, race results, restoration shops and a few chassis histories of individual cars; something for everyone interested in Bugatti. Parker’s partner Diane Murphy did a nice job writing up the sections on the Bugatti family and the two notable female Bugatti race drivers, Helle Nice and Elizabeth Junek.

I didn’t just skim this book or just read every page (as all book reviewers should do); as I said, I got INTO it. And though I’ll never work on one or drive one (but have had rides in a T35), I will never look at one in the same manner again; the book has helped me develop a James A. Allington-eye for seeing through the car and realizing what it is really like deep down inside.

So, did I enjoy this book? Does a Bugatti engine revving sound like ripping calico (no one has ever figured that one out)? You bet. Haynes could do one on every different type of Bugatti and I’d buy every one. Plus the price is right. Highly recommended for the curious among us.

Price $36.95 USD plus shipping

Dimensions: 270 x 210 mm

# of pages: 168

ISBN-13: 9781785211836

ISBN-10: 1785211838

Publication date: Tuesday, 4 September, 2018

Language: English

Author(s): Chas Parker

Order from Haynes:

Order Bugatti T35 manual

Order Ferrari GTO manual

Order Jaguar D Type manual

I graduated from High School in 1961 and having missed my opportunity to marry the Prom Queen (Pat), I got a job as an apprentice mechanic with Overton (Bunny) Phillips at his Bugatti restoration shop in So. San Gabriel, Ca. The job was listed in the classified ad section of Road & Track. I did have experience with Lancia Lambda, Mercedes 540K, Tatra and others by that time. One of the more interesting thing that I learned was how to set up the cottered crankshafts. On assembling the various parts the indexing of the rod journals and alignment of the main bearings is controlled by the angle of the flat on the cotter. Bunny would do a trial assembly on a surface plate and and take indicator readings and make notes for a baseline. Then dissemble the crank and use a surface grinder to change the angle of the flat on the cotter. After a few iterations of this the various journals would be at 90 or 180 degrees to one another as needed. Then the crank can be assembled with all of the bearings, rods, rollers ,etc. in place.This is a simplistic description of the process, but gets the idea across. If you see a Bug roller bearing crank you may notice that it is basically two 4 cylinder cranks mounted end to end and rotated 90 degrees to each other. This straight eight is just two 4 cylinder engines running 90 degrees out of phase with each other. I think this contributes to the distinctive exhaust note.