By Patricia Lee Yongue

Cars and Chicks

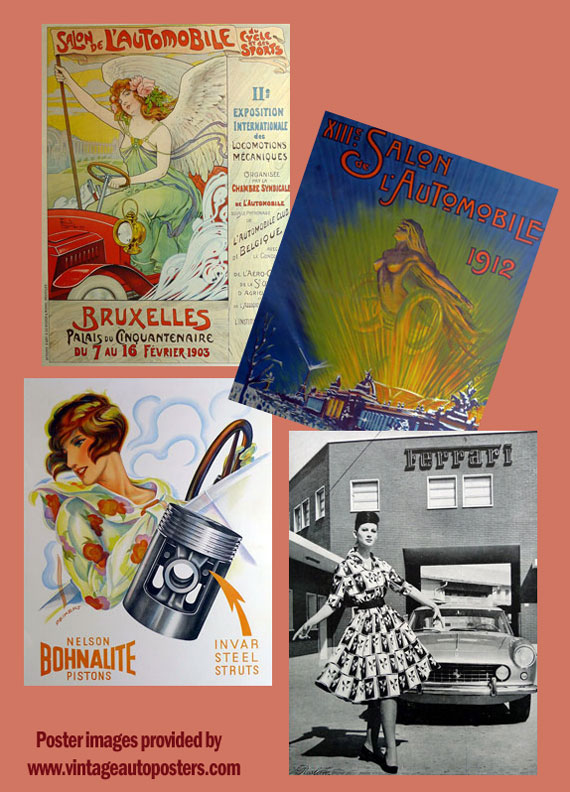

From the most elegant of international auto salons, posters, publicity photos, and magazine ads to the sleaziest of car shows and rags, a fetching female posed by—or slathered over—an attractive automobile remains an icon of Western popular culture. Occasionally, a woman sits behind the wheel and smiles through the side window. Less occasionally, she is depicted actually driving the vehicle. At the fancier shows and salons, she may move with the car by means of turntable. She and the car are assuredly objects of the ‘male gaze.’

Of late, some manufacturers have trained attractive young women to demonstrate the technology and other normally “guy knowledge” of the cars, but pretty girls talking in business-like voice about camshafts, rpms, and torque somehow diminishes the sexual sell despite the “smart is sexy” pitch. In a retro move, Ferrari offered a silent, stiletto-shod blonde-tressed female with a yellow 458 Italia at the 2011 Detroit Auto Show. And, for the most part, whether in print or at show, the non-driving, contextually sexually well-bodied and well-dressed (or undressed) young woman decorating an eminently drivable, beautifully bodied car still drives the marketer’s and, presumably, the target consumer’s desire.

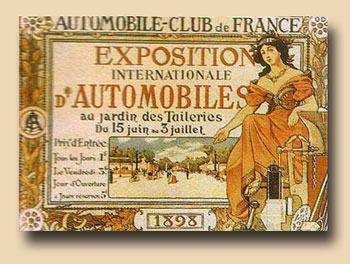

The association of decorative women and cars dates back to the very introduction of the automobile at show. The poster for the opening of the first Salon de l’auto, organized by the Automobile Club of France and held in the Tuileries Gardens in Paris in June, 1898, featured a gowned, wasp-waisted goddess of speed reigning over the exhibit. In a poster for the French constructors A. Teste Moret and Cie Lyon-Vaise, a winged young lady in fancy dress pilots a voiturette encircled by a swarm of speeding flies.

The association of decorative women and cars dates back to the very introduction of the automobile at show. The poster for the opening of the first Salon de l’auto, organized by the Automobile Club of France and held in the Tuileries Gardens in Paris in June, 1898, featured a gowned, wasp-waisted goddess of speed reigning over the exhibit. In a poster for the French constructors A. Teste Moret and Cie Lyon-Vaise, a winged young lady in fancy dress pilots a voiturette encircled by a swarm of speeding flies.

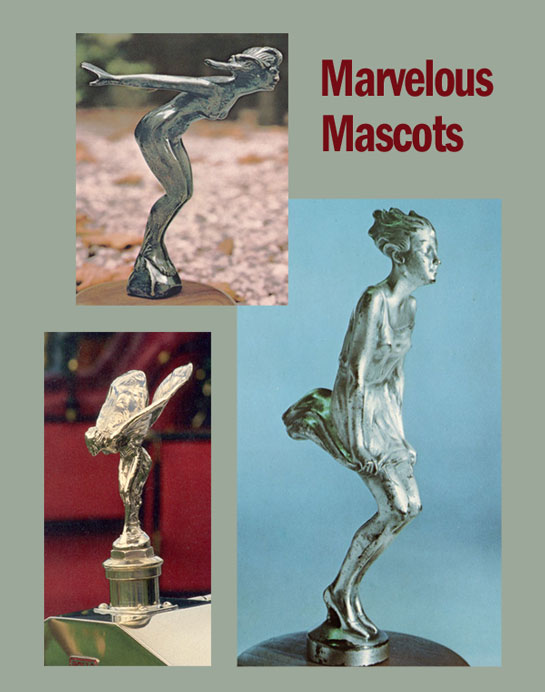

So-called “Siren” (after the fatally alluring mythological figure) ads and sculptures at auto shows entrenched the image of sexual and vehicular seductiveness in the popular mind. Charles Sykes designed Rolls-Royce’s famed hood ornament, “The Spirit of Ecstasy” (aka “Emily” and “The Spirit of Speed”), to commemorate the secret love affair between the second Lord Montagu of Beaulieu and actress/model Eleanor Thornton.

Some examples of popular mascots from 1900-1930. The Spirit of Ecstasy is lower left, credit Steve Purdy. Credit Stanley Rosenthall for nymphs.

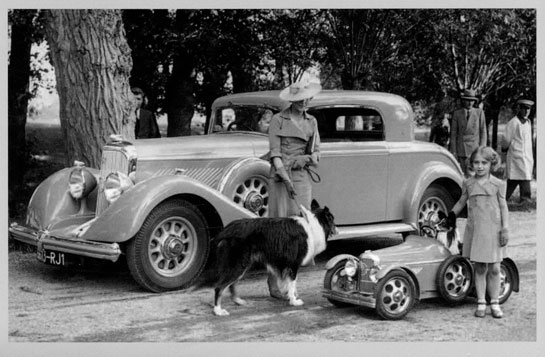

When the automobile became as much a work of art as a novel mode of transportation, during the interwar era in Europe of the grand carrossiers, sophisticated advertisements and posters frequently paired elegant women with elegant cars. British and American ads mirrored the elegance. The luxury coupe, sedan, or roadster, of course, was clearly the focus; yet, the sight and site of a fashionably garbed and attended woman (attended often by a luxury dog as well as or instead of a male companion!) poised to enter a car as passenger seemed to make the car even more desirable as a status symbol.

A photo from ‘CONCOURS D'ELEGANCE’ by Patrick Lesueur. The year is 1934, the car a Panhard 6CS; and the wife of illustrator Alexis Kow is dressed in a pale blue suit by Marry Rouf that matches the car. She is accompanied by her black and white Collie. The Panhard pedal car is by Eureka, the first one going to the Sultan of Morocco.

According to Margery Krevsky, in Sirens of Chrome, female models employed as “product demonstrators” at car shows appeared as early as 1909 in America. Photo images in Dominique Pascal’s Concours d’Elégance de chez nous also depict early French motor cars decked with mounds of flowers and graced by finely dressed women of a range of ages, though some men are depicted as well. Females developed their unique, decorative and sexually seductive intervention at shows largely in the post-World War I years, however, because of a confluence of factors, including the emergence of the New Woman, the yen for luxury and pleasure, the re-alignment of socio-economic classes in Europe, experimental marketing strategies, the democratization of the car, and, for our purposes in the next article, the resourceful practices of André de Fouquières (1875-1959) at le concours d’élégance féminine en automobile.

Cars and Chic

From the motor car’s inception, women of all ages had steadfastly occupied the driver’s seat, though most aristocratic and upper class women inclined toward chauffeured mobility. But after World War I their presence at the helm increased. Motor cars became more familiar and more accessible. War technologies hastened the development of the faster but still luxurious car, and the wealthy grew wealthier. In both Europe and America, young wealthy women, like young men, often waived the privilege of chauffeur driven cars. American women enjoyed the democratization of the car first; they also enjoyed the new trends in fashion imported from Paris usually via New York.

In pre-war years, Paul Poiret and Coco Chanel had begun to revolutionize upper class women’s daywear/informal fashion, he by loosening the harsh, constricting corset (while adding flashy feathers and other flamboyant decoration) and she more radically by introducing fabrics, notably the jersey used during wartime, suitable for graceful ease of movements such as climbing into, steering, shifting, cornering, braking, and getting out of a car. “Referring to the smart little motorcars Albert Dion and Bouton & Trepardoux were marketing, she said, ‘How can such women [dressed in “flounces and laces” and huge tulle-veiled hats] even get into a Dion-Bouton when a Rolls Royce is barely large enough for them?’” (Madsen, Chanel, p. 97).

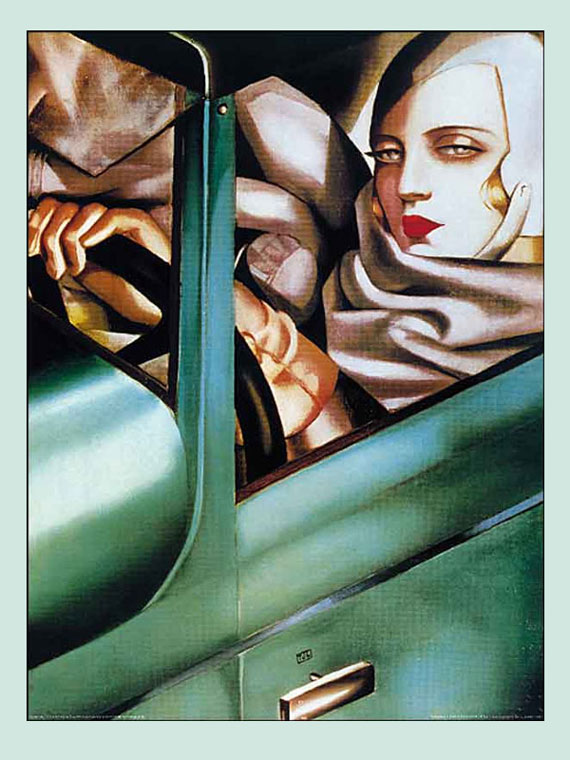

Polish artist Tamara de Lempicka’s late 1920s “Auto-Portrait: Tamara in the Green Bugatti” portrays a sophisticated self-assured young woman, obviously wealthy, in a roadster. Her gloved hand is curled firmly (some viewers say casually) on the steering wheel. Her coif is stylishly capped against the wind, her scarf lavishly compensating for covered tresses, her eyes lowered and sultry. She is mysterious, aloof, even cold, suggestively sexy.

During the interwar period, more and more young women, most from well-to-do families, took to the wheel as race car drivers. Not only because they were “the fairer sex” but also because they were unique in an essentially man’s sport, women drivers consistently drew the crowd’s and the photographer’s attention, much as American Danica Patrick commands spotlight today. Although for the camera they frequently posed demurely by their race cars, like Czech Elisabeth Junek, or jauntily on the cars, like sexy (but not upper class) French Hellé Nice, they were just as often photographed in motion, or grimy-faced after the heat of battle.

During these same interwar years, as auto journalist Catherine Stucki writes in Le Figaro, high society women who declined to race or even to motor in a sporty way (motoring was once deemed a sport) found their own “automotive” niche and way to demonstrate wealth and style. Outfitted in the haute couture of the day, they posed in a glamorous outdoor exhibition starring Europe’s and America’s most exquisite touring/passenger cars and roadsters.

Originally, in the early 1920s, in Paris and at resort areas such as Deauville and Cannes, the women posing at these concours were young models, called mannequins, representing the major couturier houses. By 1919, these live models had replaced in the fashion houses the old wooden mannequins. And just in time. After all, the automobile generated unprecedented mobility; high fashion designed clothes amenable to motion; and, women “want to see how the clothes will move” (Vogue, qtd. in Madsen, p. 97). With the exception of Chanel, oddly, who claimed she found the concours grotesque (Lesueur, CONCOURS D’ELEGANCE fashion designers enthusiastically participated in what became a competition to create a synchrony between the beautifully designed car body, in the hands of the carrossiers, and the beautifully dressed woman, in the hands of couturiers.

By 1934 Tony Lago was at the helm of Talbot France and introduced this striking 'Baby Sport' at the 1934 Paris Salon. Car and model were a harbinger of things to come for Talbot and the concours. Photo from 'CONCOURS D'ELEGANCE, Lesueur.

Anthony Blight, in The French Sports Car Revolution (p.102 ), writes that, at the heyday of the concours coachbuilders enthusiastically participated. In the mid-thirties, for example, three three-liter T150 Talbot-Lagos “stood out . . . in sensational fashion” among the 360 entrants in the concours sponsored by L’Auto held in the Bois de Boulogne: “three beautiful open touring cars, painted and trimmed respectively in red, white and blue. They had been bodied in the Société Talbot coachworks . . . and to present them [Tony] Lago had hired three well known lady drivers, each wearing identical and elegantly tailored outfits [in line with the “wholly” British style of the cars] topped by a dashing beret: Mlle Hustinx in red for her red car, Mlle Lamberjack in white, and Mme Degouy in blue” (p. 101). They won the Grand Prix in their class. So pleased was the theatrically-oriented Lago, that the weekend after the concours he “hired the sumptuous dining room of the Prince of Wales Hotel and invited every leading figure in the French motor industry to a lunch hosted by the tricolor ladies, after which they mounted their T150s again and paraded in the concours sponsored by the Paris evening paper, l’Intransigeant (p.102).

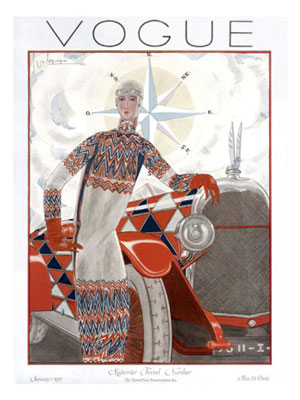

As France worked to rebuild and in fact redesign its postwar economy, which survived a series of financial crises and a growing chasm between the rich and everybody else, marketers paid increasingly more attention to the female consumer. For the 1925 Exposition internationale des arts decoratifs et industriels moderns in Paris, the event featuring the 1909-1939 style later known as Art Deco, artist Sonja Delaunay created a tableau visually and perhaps symbolically merging the automobile and women’s fashion. An example of fanciful Delaunay “simultaneity” had appeared on the January cover of British Vogue. Neither car nor woman appears prepared for movement, but the equivalence of woman and car does have influence.

We might argue that the concours d’élégance féminine en automobile constituted a backlash to the New Woman movement (literally) and a return of women to their passenger/chauffeured and ornamental status before World War I. On the other hand, as the 1920s drifted into the 1930s, the young slender mannequins were joined, or often replaced, by society women, actresses, entertainers, and occasionally race car drivers, of all ages and figures. The 1920s focus on the slim, youthful woman blurred a bit in the presence of, ironically, a more “democratic” aristocrat and celebrity.

The concours d’élégance evolved from marketing strategy in the early 1920s into a ritual social (though still commercial) event through the 1930s. Even though several major fashion houses remained open during World War II, the concours of necessity closed shop until the late 1940s.

The author wishes to thank Michael T. Lynch and Fred Simeone for kindly making research material available.

Bibliography

Blight, Anthony. ‘The French Sports Car Revolution: Bugatti, Delage, Delahaye and Talbot in Competition 1934-1939’. Sparkford Nr Yeovil, Somerset: G. T. Foulis & Co., 1966

Krevsky, Margery. ‘Sirens of Chrome and the Enduring Allure of Auto Show Models’. Troy, MI: Momentum Books, L.L.C., 2008.

Lesueur, Patrick. ‘CONCOURS D’ELEGANCE: Dream cars and lovely ladies’. Trans. by David Burgess-Wise. Deerfield, IL: Dalton Watson Fine Books, 2011.

Click here to order from Dalton Watson.

Madsen, Axel. ‘Chanel: A Woman of Her Own.’ New York: Henry Holt and Company, L.L.C., 1990.

Pascal, Dominique. ‘Concours d’Elégance de chez nous.’ Boulogne: Editions MDM, 1995.

Stucki, Catherine. “Concours d’elégance et . . . volupté.” ‘Le Figaro.’ http://www.sdv.fr/figaro/auto/dossiers/1/art5html.

Wilson, Elizabeth. ‘Adorned in Dreams: Fashion and Modernity.’ Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987.

“Le Concours d’Elégance Féminine en Automobile Organisé par L’Auto, Fémina et L’Intransigeant.” ‘L’Auto Carrosserie.’ No. 106, July-August 1933.

I would put the photographs in a different story than include them with the posters because the posters involve type, font choice, wording, and are revealing of the favorite type styles of the time.

Re photographs I have always had mixed feelings re photographs with beautiful models–because, as a guy who wants to “see the car” first and foremost, it really aggravates me to look at some picture of a rare car and see some model obfuscating something like the car’s wheel, so I can’t see what it looks like. Say with the 206GT Dino prototype I’d rather see the whole car unemcumbered than see it with a model in front of it, no matter how leggy she is. Sorry, ladies! However, in some pictures of ’30s through early ’50s concours I do get a kick out of seeing woman owners with the cars where they attempt to match the color theme throughout, maybe even dying the dog’s hair to match the car.

I also have a question for the authors: did Detroit automakers ever get into posters much? I don’t recall them, and if they did have them, were they vertical or horizontal for the most part? Where would they be used–at the dealership? Do modern automakers still issue posters?

One final comment: Maybe 40 years ago I was visiting a newspaper in Detroit and I stepped into a room that was, it turned out, a giant camera, used for photographing car ads. They had big chunks of glass on the table there and I asked what they were and they said “Lenses to stretch out the car,” and I tried one and it was laughable how you could take a stock picture of a Cadillac and add a couple feet when looking through that lens.

During the 1970’s many publicity photos were taken with attractive lady fashion models and Alfa Montreal’s -these ladies were to become known as Monti girls. There dress symbolized the ’70’s fashion as much as the Montreal did ’70’s car design.

Dale Whitney

about 45 years ago it struck me that with my small collection of lovely cars, photographs of them with lovely young ladies wasn’t a bad idea at all. i was amazed at how easy it was to find models–from art schools to the “friend of a friend.” never took a raunchy photo; told the models they could bring a chaperone if they wanted. one brought her mother who was very pleased at my work. i’m prob’ly the only person with photos of a nude on a le mans piper, lola/serenissima, cooper-mg, even a miniature chaparral h-mod. very pleasant aesthetique memories indeed.