By Paul Wilson

All Photos by Hugues Vanhoolandt unless otherwise noted.

In the late 1930s the fastest, most advanced, most beautiful sports car in the world was the Alfa 8C2900B, or “2.9.” So, of course, I wanted one.

This was back in the 1970s, when many great cars were cheap–one of the Bugatti Royales spent time in a junkyard, for example. But not the 2.9s, which dipped only to the price of a nice house. I was driving a rusty Valiant station wagon, bought for $175 when I was married. A 2.9 was laughably out of reach.

My solution, sort of, was to make one.

Not the whole car, just the body. Bodies on the great prewar classics, like the Alfas, Talbot-Lagos, Bugattis, and Delahayes, were mostly built by independent coachbuilders.

So I thought, why not build on a suitable chassis, with all of the original materials and design themes, the most beautiful body they never made back then, but should have? All the mechanical parts, the instruments, everything supplied by the original maker, could be just the same. It would be a true Alfa, Delahaye, or whatever; as when the car was new, just the body would be non-factory. I would contribute what Ghia, Touring, Farina, et al did back then, only many decades later.

Obtaining the Chassis

So where would I find a stray, neglected chassis from a great classic on which to base my project? I had almost no money, but did have timing and luck. The chassis I chose was the 2.9’s junior sibling, the Alfa 6C2500, which then could be found in scrap yards. They had a classic twincam six, the 2.9’s all-independent suspension, and huge brakes, but they were far more expensive to restore than their value could justify. They were heavy and underpowered, but their main weakness was aesthetic. They came from an awkward period (1939-52) in body design, when lean prewar shapes evolved into bulky, nose-heavy, less attractive forms.

So I bought three derelict 6C2500s. Two were picked over for parts. Nobody, including me, imagined that these mechanical parts, instruments, and hardware would ever be valuable, but the cars were rare, and if sometime I needed a spare part, and didn’t have one on hand, I’d be stuck. The only complete car I dragged home was a homely Ghia cabriolet that had been sitting outside for twenty-odd years without a top. I removed the interior with a shovel. The battered remains of the body went to the recycling center. My total outlay for the three cars was $1000.

Sexy Coupes

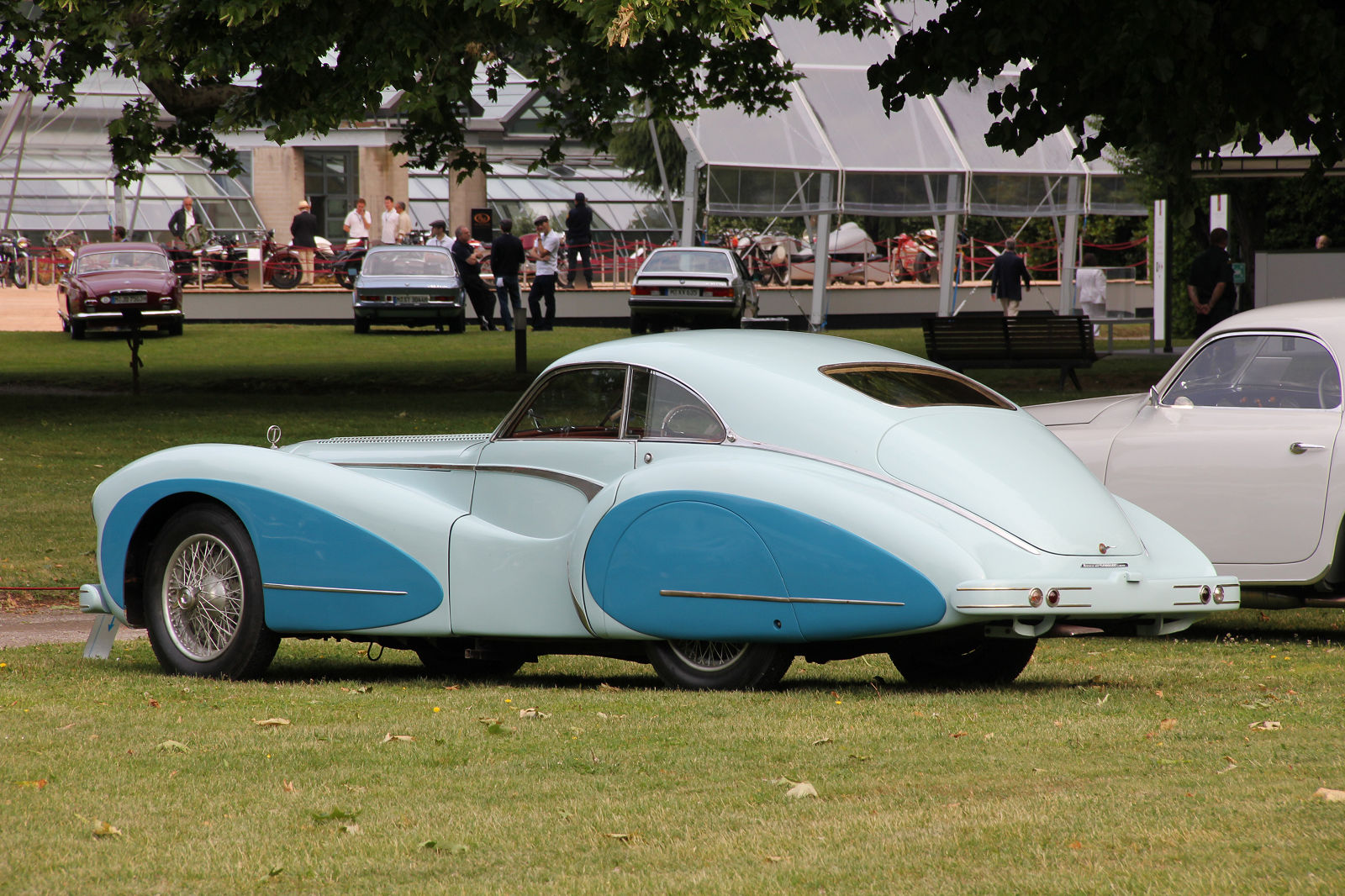

Over the next quarter century or so, as the chassis slumbered in my barn, I dreamed about the project. I imagined myself as an Italian coachbuilder in 1948, with his eye for proportions and design themes, his methods of construction, his materials. The sexiest designs were the teardrop coupes, of which a few, like this Talbot-Lago Grand Sport below, were still built after the war.

They would be more complex to build than an open car, with big doors with roll-up windows and well-appointed interiors. I had no metalworking skills, little mechanical experience, no money or serious prospect of ever having much. I did have time and space, a tolerant wife, and huge optimism. My rules were strict: It had to be a 1948 Alfa, in every detail. However, while the car was to be a correctly restored 6C2500, with everything Alfa supplied to its coachbuilders in period, it could be a synthesis of all the best then available. If I made the body myself, I could make it exactly as I liked. I didn’t have to imitate a feature I didn’t like, if at that time, something better was possible.

After carefully studying the great designs of the era, I decided that none of them got things 100% right. Take, for example, that Touring-bodied Alfa 2.9 coupe I wanted to buy in 1975 with that trust fund I never got. I love its long nose, slinky proportions, and teardrop fenders. And yes, it did win Best of Show at Pebble Beach.

But is it “as close to perfect as anyone will come in combining function and aesthetics,” as style expert Bob Cumberford writes? Even he objects to the squared-off window line that conflicts with the car’s curves, and notes the “wartlike rear lamp cluster, stuck on as though it were an afterthought”.

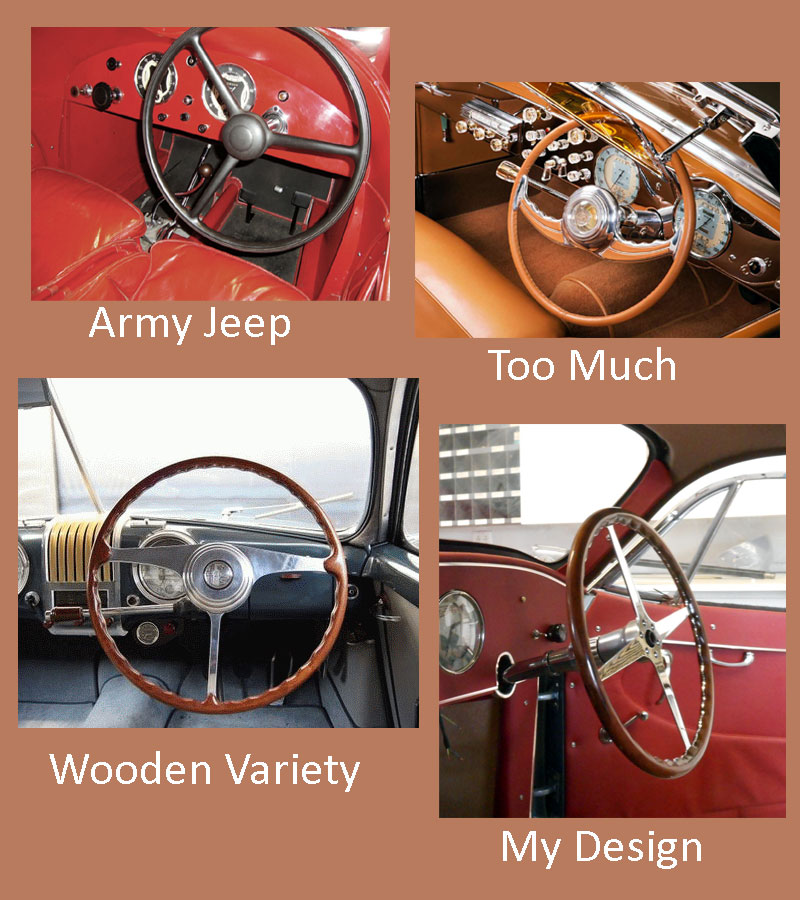

The flat windshield is less racy than a vee. To me, the rear view is high and awkward. And the steering wheel looks like something recycled from an army jeep. Why not a gorgeous wood-rimmed alloy wheel like the contemporary Bugatti Type 57s had?

The Object of My Perfection

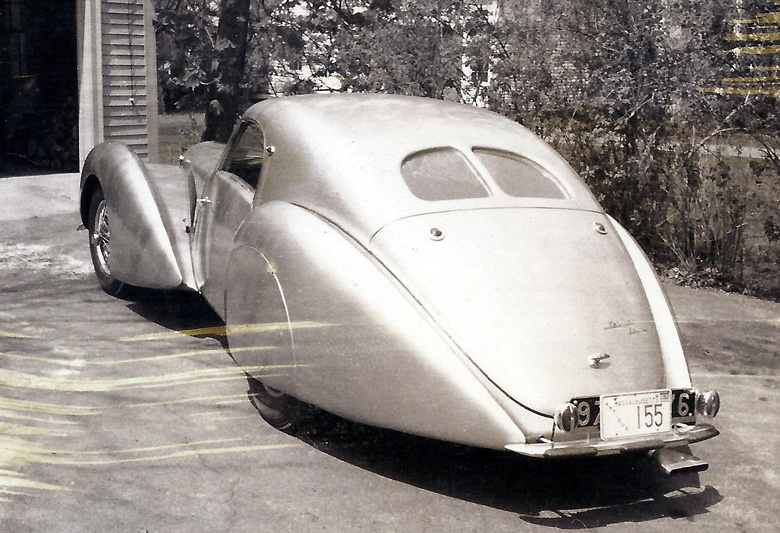

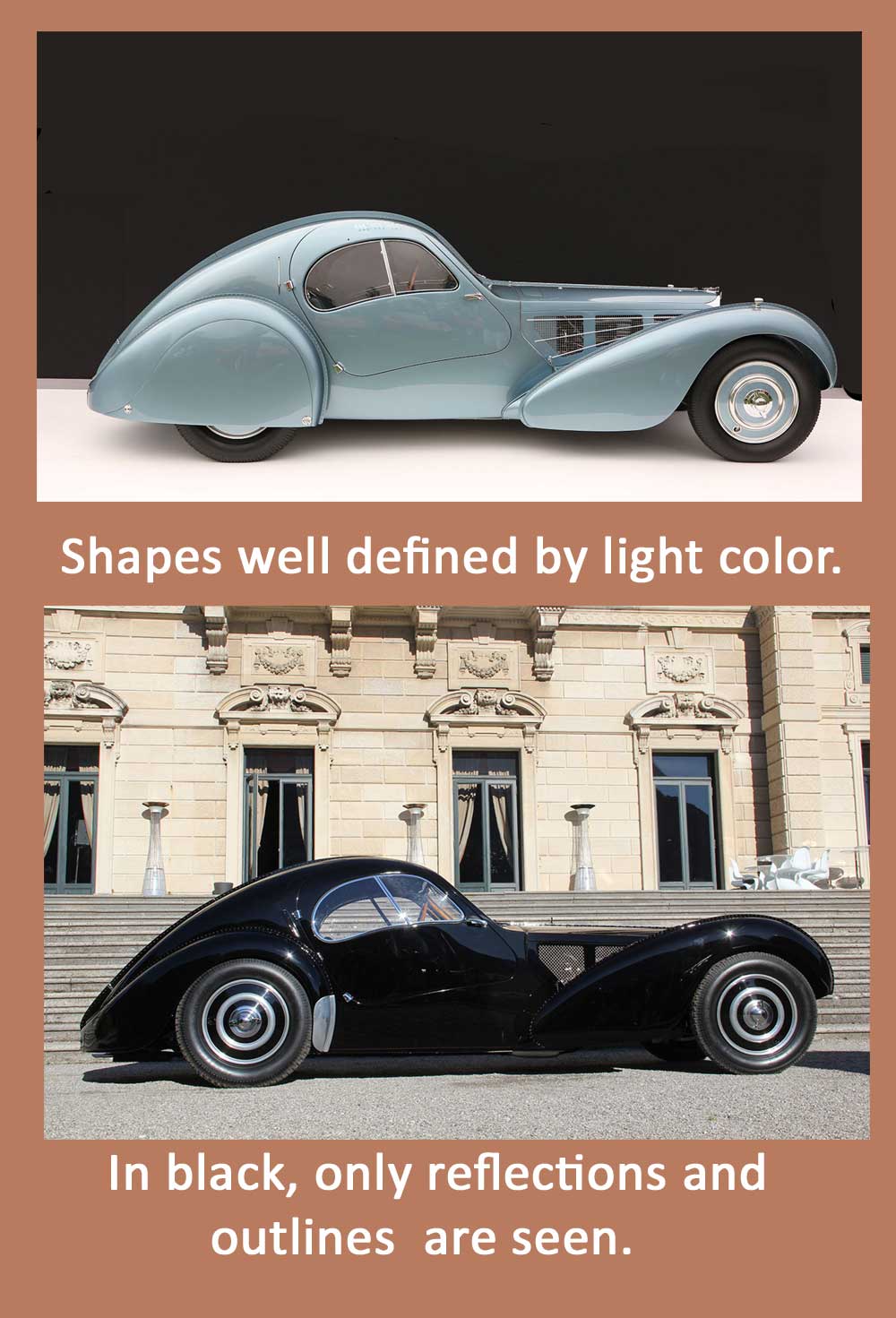

For me the closest to perfection, of the teardrop coupes, is this Pourtout-bodied Talbot-Lago that drove past me one day around 1969 in Boston. I took this picture after following the car to its home. The smooth harmony of those tapering shapes is fantastic. In my Polaroid photo the bumper, taillights, and license plate make a mess, of course. When that car was restored and won Pebble Beach, this aesthetic problem was solved by omitting all this clutter.

It does look better without lights or license plate, but . . . ? A backward step was the restorer’s choice of color. Silver showed every nuance of the form; in dark blue, the shape dissolves in glitter and highlights. All you see is reflections. Black and dark colors make any car look like a diamond necklace, and apparently show judges like that, but if you can’t see the contours of a body like this, you miss the point.

Delicious Delahaye

Another inspiration for my body design was this Delahaye. Chapron made one of these bodies on the V12 chassis in 1939, and a few more after the war. In about 1962 I saw the original car sitting outside, derelict, windows down, with the disassembled engine in the passenger compartment, behind the Clark museum on Long Island.

I wrote to the owner, trying to buy it, but got no reply. The fenders are dramatic, the front and rear are graceful, and nothing about it is weird or exaggerated (except perhaps those front fenders). With a notchback instead of a fastback, it’s not as racy as the Pourtout Talbot-Lago, but still wonderful.

Don’t Forget Figoni

A journalist describing the Figoni et Falaschi Talbot-Lago coined the term “teardrop” for this style of wind-sculptured coupe body. With this subtle light and dark gray two-tone, I think this car is fantastic. From the rear, I don’t like the vestigial fin, the bullet taillights, the excessive chrome trim, or the wing-style bumper. The front view is dramatic and smooth, consistent with the aerodynamic theme.

Atlantic and Atalante

The Bugatti Type 57 is one of the benchmark teardrop coupes. One of the three Atlantics is rumored to have sold recently for $47 million. It’s low and rakish, with a long hood and graceful fenders, but the side window shape doesn’t flow with the rest, the square edge of the hood clashes with the curvaceous aero theme, and the front is an illogical clutter.

The square vs. curved clash also appears on the Type 57SC Atalante: the outlines of the doors and hood are aggressively squared off. I prefer a design where all elements harmonize with the overall theme.

So, I was going to improve on these, was I? That was the idea. Next week, Part 2

I have seen my friend Paul Wilson s coupe as well as the beautiful cabriolet he is building now.

Fantastic work and attention to incredible detail.

What amazing design and workmanship! Paul is talented. His attention to detail is astonishing.

Interesting to read about the design inspiration behind this beautiful C21 retrocreation. It’s a beautifully proportioned machine and the “Going fast while standing still” look is sublime. Thank you, Mr Wilson, for both your foresight in saving all those junk 6C-2500 bits and your stamina in following your dream to reality.

I worked with a fellow in Spokane WA years ago who told me about his father’s 8C2900B. He bought it back in the 60’s , it was drivable and completely original. This took place in the Midwest, I believe Kansas. Long story short, he had it stored in a barn on his farm. One night lightning struck, barn and numerous cars where completely consumed. Afterwards a giant hole was dug and everything buried. Fast forward, one day a knock on his door started negotiations into retrieving the remains. Also buried along with the 2.9 was a pontoon bodied Ferrari that had competed at Sebring. The guy who instigated the retrieval was from Italy. The skeleton remains where uncovered of both vehicles. The serial number plate of the 2.9 offered the ability to reproduce a replacement. It’s been thirty years since I was told this story so I might be mistaken in some details…the rebuilt 2.9 was eventually sold to a person in Japan.

Adding to Jacks story, the Alfa 2.9 was unearthed, restored, and sold at Bill Noon’s Symbolic Motors establishment. The farm was near Clarksville, Missouri, a small town north of St. Louis on the Great River Road (Missouri #79). We stopped there for lunch in the city park, a few other people gathered, and we learned they were preparing for a chili cookoff the next day. One thing led to another, the Budweiser trailer arrived, and we were invited to stay and asses the purity of the brew. Discussing chili cookoffs led to Carrol Shelby’s chili activities, and cars in general. Someone then mentioned the guy with a farm and a bunch of fancy cars. Something clicked and I asked if the barn burned and sure enough, we were in the city where the 2.9 Alfa burned.

Here’s more: https://barnfinds.com/burned-buried-alfa-romeo-8c-2900b-corto-spyder/