Learning from the Americans:Planned Obsolescence and Airflow influence

By Gijsbert-Paul Berk

In 1920, Alfred Sloan was appointed to save the ailing General Motors. As we have seen in part 3, Sloan had learned from contacts with dealers and client surveys that styling sold better than advanced engineering. This was one of the reasons why he engaged Harley Earl to set up an Art and Color department at GM, the first professional in-house styling studio in the world.

To increase the output of GM’s factories, Sloan and Earl introduced annual model changes. The idea was to seduce the public to buy a new model, long before it was economically or technically necessary to trade in their present car. This strategy became known as ‘Planned Obsolescence’.(If you would like to know more about its effect on car design and marketing, read “My Years with General Motors” by Alfred P. Sloan. It was first published in 1963 but second-hand copies are still available from Amazon and AbeBooks.)

The great depression that followed in the wake of the Wall Street Crash of 1929 had grave consequences for the societies in many countries, and thus for the car manufacturers in the USA and – with some delay – of those in Europe. A great number of smaller companies did not survive the economic downturn while many workers became jobless. In Germany and Italy poverty and social insecurity would lead to the rise to power of National socialist and Fascist governments.

At the first signs of economic revival after the 1928 – 1933 depression, the car industry in the U.S. rediscovered its dynamism. It was the beginning of a new era, one of optimism and confidence, and also the era of the so called ‘streamliner’.

The concept car or dream car ‘originated’ in the U.S.A.

One must admit that it was an extremely clever marketing idea; give the public a foretaste of the future by exhibiting a concept – or dream car. One of the first of its kind was probably the rear-engined Briggs Dream Car, designed by the Dutch born engineer John Tjaarda and displayed on the Ford stand at the Chicago Century of Progress Exhibition (1933-1934).

One of the first futuristic dream cars was probably the rear-engined Briggs Dream Car, designed by the Dutch born engineer John Tjaarda and displayed on the Ford stand at the Chicago Century of Progress Exhibition (1933-1934). It must be said that the concept of a rear-engined and aerodynamic car was in itself not new. As we have seen in a previous article, Edmund Rumpler, Emile Claveau and Charles Dennistoun Burney had already pioneered such a lay out and in Czechoslovakia Hans Ledwinka was working on his Tatra T 77.

Around 1934 Mercedes-Benz built a small number of experimental mid-engined prototypes for competition purposes. These Mercedes Type 150s (there was also an open roadster model) were equipped with a four cylinder side-valve engine of 1.498 liters and could reach 125 km/h (78 mph). Their front, like that of the Briggs dream car, foreshadowed the one of the future (KDF) Volkswagen.

GM’s Harley Earl, who can be regarded as the originator of the profession of car stylist, became a firm believer in the use of concept cars for exhibition purposes. For the 1933 Chicago Fair he designed the two-door Fleetwood Aero-Dynamic Coupe for the Cadillac V12. But this was in fact more of a design study for a limited series than a futuristic dream car. But in 1938 Earl unveiled his Buick Y job. This would be the forerunner of many GM concept cars such as the 1951 Le Sabre and of course the legendary gas-turbine powered Firebirds.

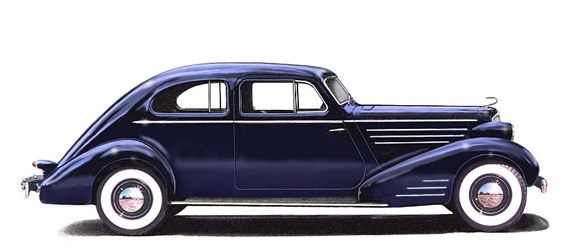

For the 1933 Chicago World Fair, Harley Earl designed this two-door Fleetwood Aerodynamic Coupe for Cadillac. A design study on a 154-inch (392 cm) wheelbase Cadillac chassis for a limited series of cars, it was to be powered by the new Cadillac V16 engine, introduced in 1930. Unlike most other cars of its time, the spare wheel was housed in the trunk. If the fastback rear suggested streamlining, the rather conventional front-end was not very efficient from an aerodynamic point of view. However, its appearance presaged future GM models.

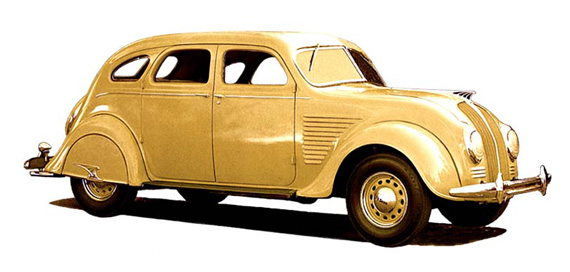

The Chrysler Airflow was not a dream car

Over at Chrysler, streamlining was much the rage. Walter Chrysler wanted to manufacture an aerodynamic car that would ‘slip through the air’. The resulting ‘Airflow’ model was never presented as a concept car.

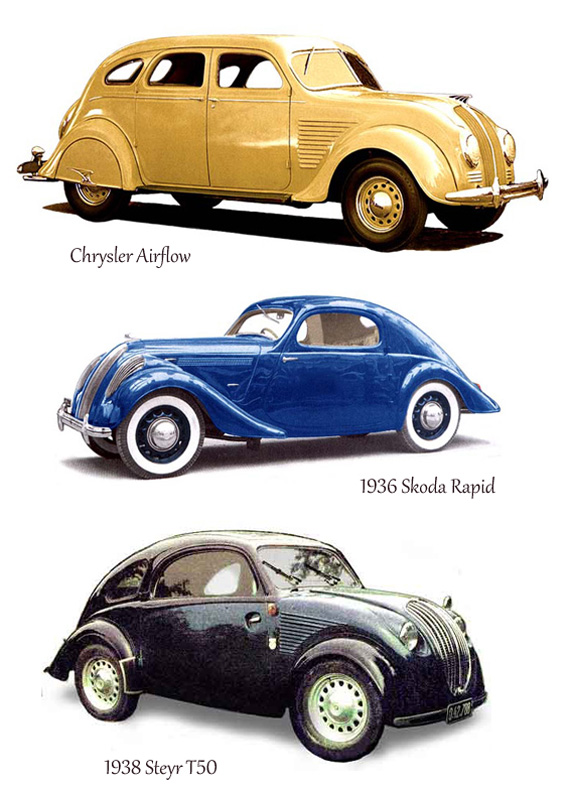

The aerodynamic – but perhaps too futuristic – 1934 Chrysler and De Soto Airflow range (developed by Carl Breer, Fred Zeder and Owen Skelton with some input from the Hungarian aerodynamic wizard Paul Jaray) were serious production models. Unfortunately they were also a serious commercial flop. (This has always amazed this author, because the Peugeot 402, which looks very similar to the Airflow, was quite a success in Europe.) The ‘waterfall grille’ that adorned the front of the Airflow proved very popular with European designers. It was not only used on Peugeots (with the headlights behind the grille) but also on the Adler 2.5 liter Autobahn cruiser, a range of 1935 – 1938 Fiat models, and less well known, the small 1938 Steyr type 50 and the Skoda Rapid Coupé.

Edsel Ford turned a dream into reality

Ford was not idle either. At the request of Edsel Ford, the Briggs Dream Car concept was redesigned by Ford’s in-house styling boss Bob Gregorie, to become the front-engined Lincoln Zephyr and Briggs was awarded the contract to supply its body panels. Gregory would later design the Lincoln Continental Convertible, based on sketches made by Edsel Ford while in Europe.

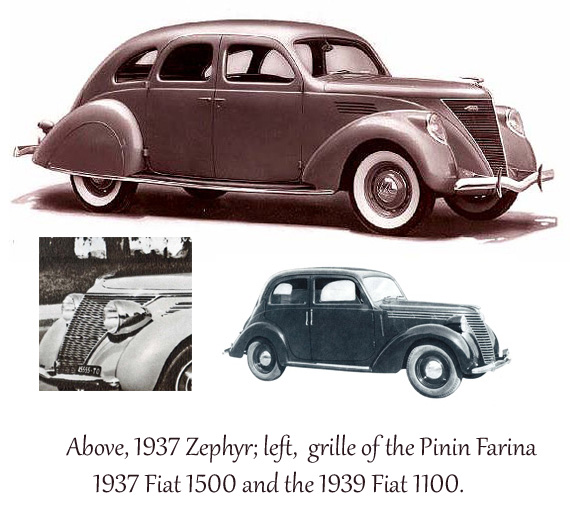

The rear of the 1937 Lincoln Zephyr still shows some of the DNA of the Briggs Dream Car concept exhibited on the Ford stand at the 1933 -1934 Chicago Century of Progress Exhibition. The design of the body of the front-engined Lincoln Zephyr was the work of Ford's in-house stylist Bob Gregory. Gregory had been trained as a yacht designer and the front-end treatment of the Lincoln Zephyr resembled the prow off a boat. Interesting to note that the same design was not only used on the next generation of Ford products, but soon also replaced the waterfall grill on Fiat’s 1100 Ballila, the Fiat 1500 sedan and even Pinin Farina used it on some of his special bodies. Renault, whose styling became more and more Americanized, also adopted the pointed radiator grill.

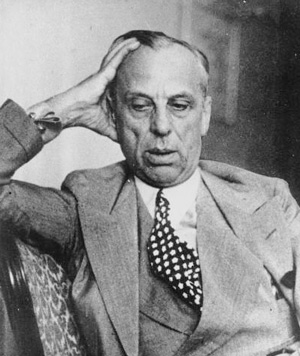

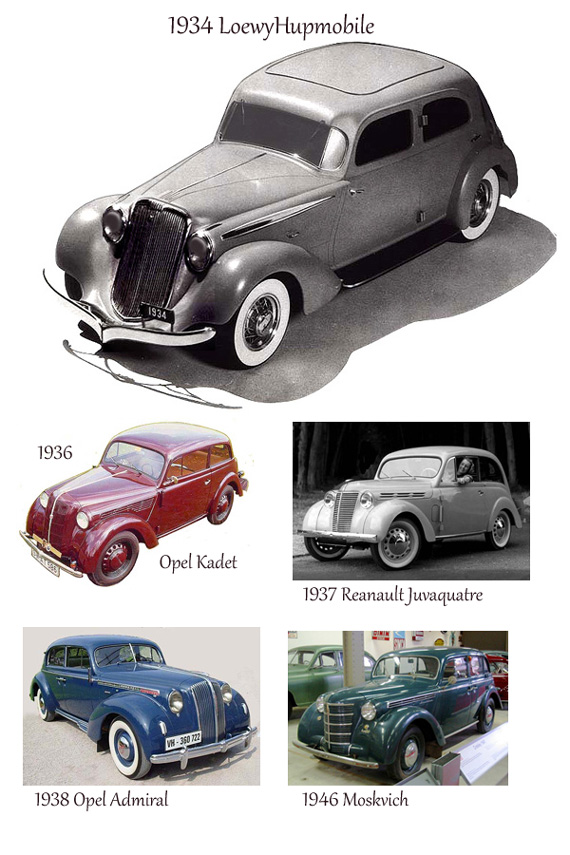

Lowey and the Hup

Although he was born in Paris (France), Raymond Loewy became one of the best-known industrial designers in the U.S.A. He and his associates designed duplicating machines for Gestetner, streamlined locomotives for the Pennsylvania Railroad, buses for Greyhound, vending machines for Coca Cola and the interior of the NASA Skylab. Loewy was also involved in the styling of automobiles. Around 1932 Hupp Motor in Detroit approached Loewy to assist Amos Northup with the design of a new Hupmobile. The result was a mixture of modern streamline and Art Deco. The 1934 Aerodynamic Hupmobile featured a raked front grille, a three-piece windshield (also seen on contemporary French Panhard cars), a smooth rear end incorporating the luggage compartment with an inboard spare wheel, and aerodynamic door handles. But the most original detail was the way Loewy integrated the headlamps in the large hood covering the engine compartment.

Unfortunately the Aerodynamic Hupmobile was not well received by the public and for 1936 it was redesigned to look more conventional.

Was the design, like the Airflow, too advanced for the American taste of that time? There is an interesting postscript to this story. In 1936 Opel, then a German subsidiary of General Motors, introduced its Opel Kadett. That car was virtually a small clone of the Loewy Hupmobile. A year later Louis Renault borrowed the design for his Juvaquatre and in 1938 Opel also styled its flagship Admiral line with a bonnet that integrated its headlights. After the Russians occupied part of Germany they took over the production of the Opel Kadett and called it the Moskvitch.

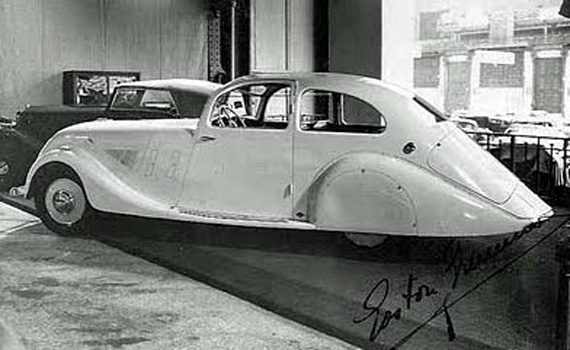

Paul Jarray acted as aerodynamic consultant for various car manufacturers. Here is one of his most impressive designs, a Maybach Zeppelin, as exhibited on the 1935 Paris Motor show. The small window in the windscreen helped the ventilation of the interior.

Meanwhile in Europe, most cars were still shaped by engineers

Whereas the popular American automobiles gradually became larger and more powerful with a smooth six cylinder or a V8, in Europe large displacement cars were still a luxury. High fuel prices and progressive taxes on the cubic capacity of engines forced the leading European manufacturers to concentrate on the design of smaller economical cars.

Another clean aerodynamic design, presumably also by Paul Jaray, this time a special BMW 328 coupé, exhibited at the 1938 Berlin Motor Show.

Most bread-and-butter cars in Europe were still shaped by engineers, sometimes with the help of in-house stylists – for instance Flaminio Bertoni at Citroën and Louis Bionier at Panhard – or independent consultants such as Jean Andreau, George Paulin or George Ham in France and Roy Fedden in the UK.

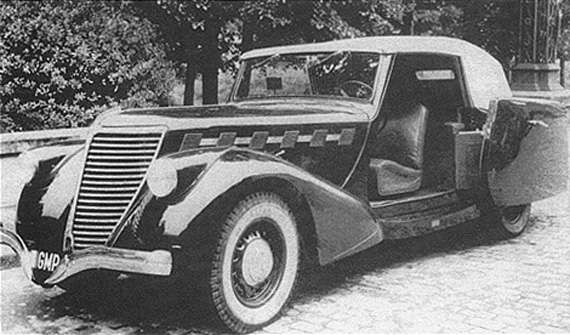

A unique convertible body by Jaqcues Saochik on a 1937 Renault Suprastella chassis. Note the Americanized grille of this large Renault and the pivoting door to facilitate easy entry in narrow parking places. This was a construction patented by the coachbuilder.

Because European manufacturers generally feared that their competitors would discover what their designers were working on and steal their ideas, cars that were not finalized for production were never shown in public. And there went the idea of the concept car in European terms.

After serving in the French Air force during WWI, Gaston Grümmer started a coach building company, catering mainly for the rich and famous. His creations won many prizes at concours d’elegance, in part because he always took care to have them presented by the most gorgeous female models. In the early 1930 ties with the help of Etienne Buneau- Varilla, an aviator friend, he developed the concept for a series of advanced aerodynamic designs that could be mounted on the chassis of various makes. He patented his designs as l’Aeroprofil. Apart from the long sloping tail and enclosed rear wheels, one of the most remarkable characteristic of this design was the way the windows were horizontally divided, the upper part tilted on to the roof. Grummer build several Aeroprofil bodies, One, using a Hotchkiss chassis, made its debut at the 1933 Salon de l’Auto in Paris. Another, on a Delage D8 chassis, went to the States and was exhibited at the New York Motor show in 1934.

In all fairness, car makers in Europe at that time did not really need to produce their own dream- or concept cars. Most of them had a close relationship with specialist coachbuilders. To whom they also often confided the design and construction for small series of bodies for their more sporting or exclusive models. The exhibits of these coach building firms at the various Motor Shows, more than once unveiled interesting or futuristic design trends. But that is another story.

Read Part 1

Read Part 2

Read Part 3

Read Part 4

>

The BMW328 referred to as a Jaray design in fact was designed by Reinhard Koening-Fachsenfeld.

Martin Schröder

Sometime about 4 decades ago, in one of the US foreign car mags, someone editorialized that German cars were both engineered and styled by engineers, American cars were engineered and styled by stylists, but French cars were engineered by stylists and styled by engineers.

It’s probably true that European car buyers were more brave when selecting new car designs. Just think of the post war Citroën DS.

See various variants of the mentioned Peugeot 402 1935-1942 here

https://www.google.dk/search?q=peugeot+402&client=firefox-a&hs=WgM&rls=org.mozilla:da:official&tbm=isch&tbo=u&source=univ&sa=X&ei=FQKVUZWAFsPStAb99ICQDQ&ved=0CCsQsAQ&biw=1366&bih=665

Great article on style. However Gregory, Ford stylist should be spelled Gregorie.

BTW, the annexation of the Russians of the Opel Kadett had nothing to do with the Soviet Union occupying the eastern part of Germany. Opels were produced in the western Part of Germany, Rüdesheim, part of the western allied zone. No, they got the Opel Kadett production machinery as war compensation; they had a train with loco and wagons transporting the hole lot to the prewar Polish/Russian border and reloaded the lot to a Russian wide track train and on to Moscow. The German loco and wagons stayed in the eastern block.

An article on ’30s aerodynamics without the Tatra?? Alas, the whole focus on tapered rear ends was, postwar, proven backward- by Colin Chapman/Lotus, etc. on the track- and such as the ’60s production Alfa Giulia sedan rear cutoff. Focus on the front of the vehicle? Of course.

I think one of the reasons the Airflow was a commercial flop had to do with proportions. When you look at the other two examples that have a similar front end treatment, the Skoda and the Steyr T50, appear to have better proportions, probably because they are shorter. One of the other reasons the Airflow was a commercial failure was in its production method of using a space frame welded to a conventional ladder frame with the body panels welded to the space frame. There were many production problems that resulted in poor fit and late deliveries to Chrysler dealers. It was an early attempt to build a unibody vehicle.

My Grandfather purchased a 1934 Chrysler Airflow when I was about 6 yrs. old and kept it like new until 1950. He allowed me to drive it occasionally. It never got wed except to be washed or if caught in a rain storm and that was very rare. He sold it with 40,000 on it for $800. It had fender skirts, that he took off in the winter just in case of an emergency and chains might be needed. (never happened) The purchaser of the car didn’t get the skirts and they went in the trash. If I had only kept that car.

Tjaarda and others were inspired toward aerodynamic car design by initial work started in 1921 by Austro-Hungarian engineer Paul Jaray, who began testing car models in aircraft wind tunnels. Jaray later used this data to design the streamlined 1933 Tatra 77 built in Czechoslovakia, which remained in production into the 1990s.

Re the Briggs dream car, I heard that before WWII, Prof. Porsche visited Tjaarda and inspected the car and if you look at an early beetle next to the Briggs car, the VW looks like a scaled down version.

Also I have a question about the 1939 Bugatti 57C Prince of Persia car (now in Petersen Museum) , if anybody has ever seen a picture of the car when new, if they know if it had the skirts on it then fore and aft? I figure if it was a copy of the Delahaye 165, it had to, since the Delahaye 165 had them but maybe the skirts didn’t get added until the car was restored in England many decades later.

Dont’ forget the Tucker Torpedo. It was a 1948 model year and was a streamlined, rear engined, four door that captured the American attention when it was revealed. It was designed by my uncle Alex Tremulis. Check out Alex’s career and another of his streamlined creations at http://www.GyronautX1.com. My brother Steve created the site to pay homage to Uncle Alex and the Gyronaut X1. There are many pictures and references to Alex’s storied career in automotive design.