Story by Gijsbert-Paul Berk

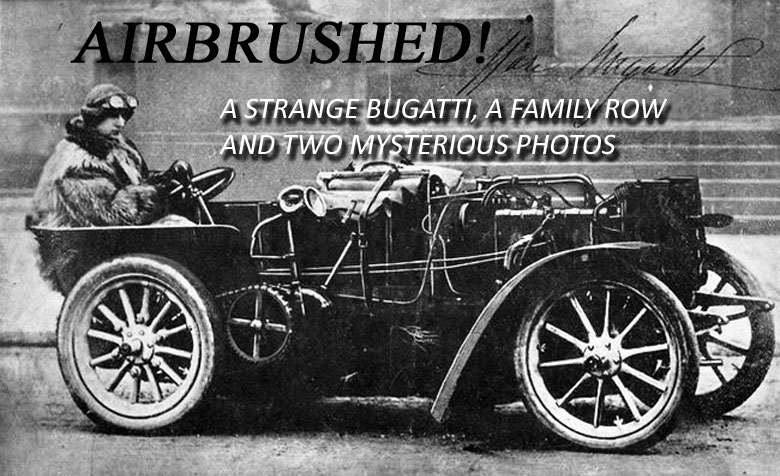

Why did Ettore Bugatti alter this photo?

The story behind them is an eye opener.

French born Eugene De Dietrich was a member of the influential Alsatian family which in 1684 established the foundry and metal working enterprise bearing his name at Jaegerthal, near Niederbronn-les-Bains. De Dietrich et Cie was an important manufacturer of machine tools, railroad material and equipment but also of heating systems and household goods. 1

After the annexation of Alsace-Lorraine by Germany in the wake of the Franco-Prussian War (1870- 1871), the family decided to stay near their factories and safeguard the jobs of their employees. Therefore from 1871 until the armistice of 1918 they became German citizens and their products were ‘Made in Germany’. This meant that they were effectively excluded from the lucrative French market for railroad stock. To compensate, in 1896 De Dietrich decided to diversify into the production of automobiles.

Together with his nephew Adrien De Turckheim, he managed to obtain the manufacturing rights of automobiles designed by the Frenchman Amédée Bollée for their factory at Lunéville. These cars proved to be outstanding and were quite successful in competitions. In the same period, the Niederbronn plant produced a small single cylinder ‘voiturette’ under license from Vivinus of Schaerbeek in Belgium.

Enter young Bugatti

Then, during a visit to the 1901 International Exhibition at Milan, Eugene de Dietrich saw a very smart small four-cylinder motor car. It was designed and built by the 19 year-old Italian Ettore Bugatti. The organizers of the exhibition had awarded his design with a gold medal-or a ‘fine cup and diploma” 2 and this machine had also won an award from the Automobile Club of France. De Dietrich decided on the spot to engage the young designer, but as Ettore was still a minor his father Carlo Bugatti had to sign his contract.

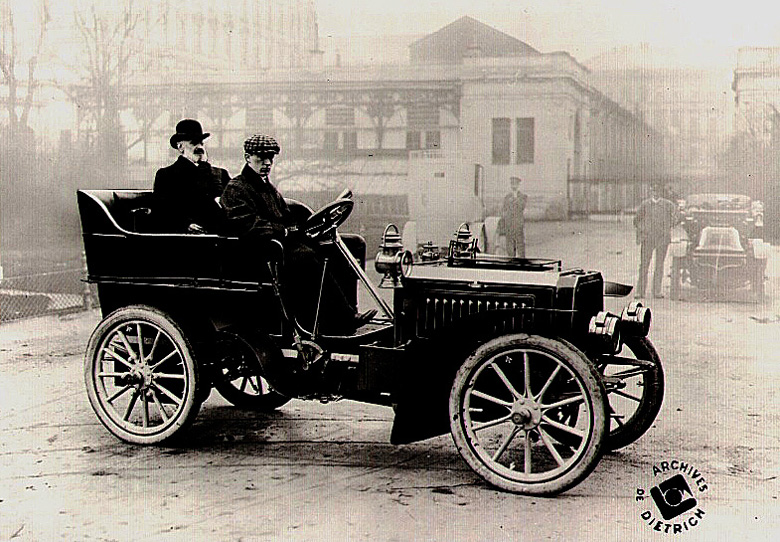

One of the first De Dietrich–Bugattis, with Ettore at the steering-wheel and Baron Eugene de Dietrich in the rear seat.

For such a young man, the contract conditions were very favorable. Ettore would get a retainer of 50,000 francs, 20,000 payable the day he started at De Dietrich. Furthermore, he would get royalties for each De Dietrich-Bugatti sold, which on average amounted to about 10 % of the factory price. And he also had the right to sell these cars directly in Italy.

By June 1902, Bugatti was busy in Niederbronn. He was not only responsible for the design but also for the construction of the cars. For their marketing, De Dietrich had engaged Emile Mathis, the twenty-two year-old son of a hotel owner in Strasbourg. Bugatti and Mathis not only worked well together, but shared a passion for motor racing and became friends.

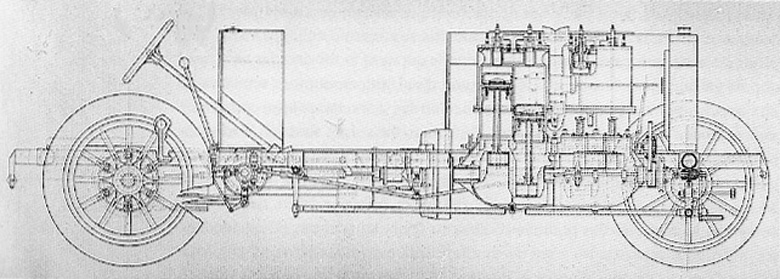

Among the three types of chassis Bugatti designed at De Dietrich was a racing version of the 12,900 cc, 60 HP, also known as the De Dietrich-Bugatti number 5. Its four-cylinder engine consisted of two large cylindrical ‘blocks’ connected by copper water pipes. Each block housed two cylinders of over 3.2 liters capacity (bore x stroke 160 x160 mm). With this powerful machine Ettore wanted to participate in the 1903 Paris-Madrid road race. However, to his bitter disappointment the organizers refused to let him start. The reason was that Bugatti had installed the seats of driver and co-driver very low and at the extreme rear end of the vehicle (in fact behind the rear axle) and the officials were convinced that the driver could not see well enough over the luggage and engine in front of him to have a clear view on the road ahead.

A drawing of De Dietric-Bugatti 60 HP ‘Course’ chassis. Why did Ettore chose the unconventional seating position, practically behind the rear-axle? Was it to enable him to sit lower or did he want extra weight at the back in order to improve the traction of the rear wheels on the road, like today’s ‘Dragsters?’ (Illustration courtesy ETAI Paris, France)

Their decision may have saved Bugatti’s life and that of his co-driver who was presumably going to be Mathis. The fateful 1903 Paris-Madrid was run on public roads and there were so many accidents, injuring and even killing participants and bystanders, that the French authorities ordered the organizers to cancel the race at Bordeaux and had the surviving cars return by rail.

Exit young Bugatti

In the meantime, in 1902 Adrien De Turckheim had (without consulting Eugene de Dietrich) arranged a partnership with Léon Turcat and Alphonse Méry of Marseille. Their objective was to build the powerful and sporting Turcat-Méry cars in the factory at Lunéville. In due course this activity would lead to the creation of Lorraine-Dietrich automobiles, a make that survived until 1935.

But Eugene de Dietrich apparently did not agree with his nephew’s initiative. In 1905 he decided to stop the production of automobiles at Niederbronn. At the same time the Lunévile activities were spun off as a separate limited company: the ‘Société Lorraine des Anciens Etablissements De Dietrich et Cie de Lunéville.’ However, according to Griff Borgeson, who had seen a letter of dismissal in the Uwe Hucke collection, Bugatti was terminated because his cars were unreliable.2

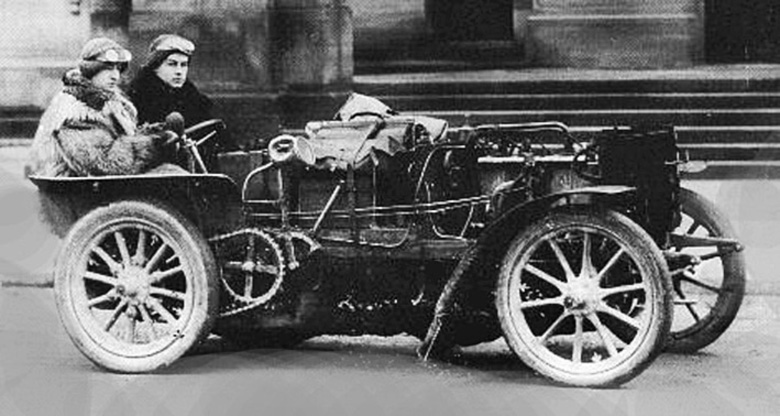

Another photo of the 1903 Paris-Madrid car. The mid-section of the chassis could be used for tires, luggage or even passengers. Clever, but the officials of the Automobile Club de France refused to let him start with the car.

Whatever the reason, Ettore Bugatti and Emile Mathis had to find new employment. Mathis was eager to establish his own enterprise and he asked Bugatti to join him. He rented a small workshop at 54 Faubourg de Pierre in Strasbourg and arranged for a big room for Ettore to put his drawing board at his father’s Hotel de Paris. The financial arrangement between Bugatti and Mathis was straightforward: Emile (or his father) would finance a prototype up to a maximum of 15,000 francs. The target cost price of a chassis was set at 10,000 francs. Ettore was to receive 2,000 francs per car for the first twelve. His royalties would diminish at a sliding scale as the volume increased.

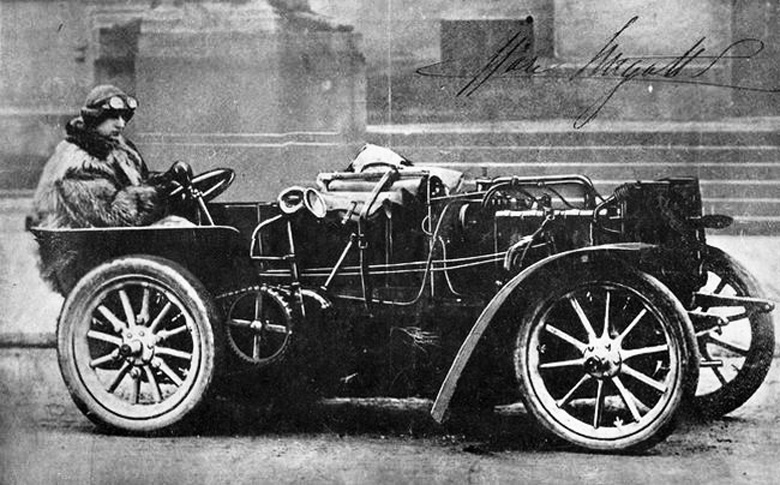

The original photo of Ettore Bugatti, with Emile Mathis as passenger, during a trial run with De Dietrich-Bugatti, designed for the 1903 Paris-Madrid race.

Assisted by a young mechanic by the name of Ernest Friderich, they developed the Ettore-designed Mathis-Hermès (Sysème Bugatti). About 25 of these cars were built by the Société Alsaciemne de constructions Méchaniques (SAM) at Illkirch-Graffenstaden, of which a few were even sold in Belgium and Great Britain.

Unfortunately their collaboration did not last very long. Mathis wanted to expand his ‘Mathis Palace’, a car dealership representing Fiat, De Dietrich, Panhard-Levassor and Stoewer, as he was primarily interested in marketing cars. But Bugatti wanted to build automobiles simply because he was fascinated by ‘la belle mécanique.’ In 1906 Bugatti and Mathis went their separate ways and the friendship eroded into animosity. By that time Bugatti detested Mathis, Said his son Roland Bugatti, “He was one of those people who want all the credit.” 3

That is probably the reason why the two photos are different. When in 1909 Ettore Bugatti needed the illustration of his 1903 De Dietrich racer for his Curriculum Vitea he asked the photographer to airbrush out the figure of Emile Mathis.

Postscript: In 1918 Emile Mathis resumed building automobiles on a large scale. By 1927 his company already produced 20,000 cars a year, which placed it in fourth position among the French manufacturers. When in 1932 France – like the rest of the Western world – experienced an economic recession, and selling American cars in France became problematic because of the high import duty, Ford and Mathis entered into a joint venture under the name of Matford SA Française, The Matfords were in fact locally assembled versions of contemporary American and British Fords, adapted to the French market. Production ended in 1940, when the Germans again occupied Alsace-Lorraine.

As everyone now knows, Ettore Bugatti became an icon in his own right.

Notes

1 Eugene de Dietrich never regained his French citizenship. He passed away eleven months before the Armistice of November 1918, when Alsace-Lorraine was returned to France.

2 See Borgeson, page 41

3 Borgeson, page 46

Sources

‘Bugatti Magnum’ by Hugh Conway and Maurice Sauzay, published in 1980 by E.P.A. Paris

‘L’Epopée Bugatti” by L’Ébé Bugatti, published in 1966 by Edition La Table Ronde and Action Automobile, Paris

‘Bugatti by Borgeson’ Griffith Borgeson, Osprey 1981

None of the photographs illustrating Gijsbert-Paul Berk’s article does in fact show the envisioned 1903 Paris-Madrid contender. The actual car is only shown in the drawing captioned “drawing of De Dietric-Bugatti 60 HP ‘Course’ chassis”.

The better reference for information about Bugatti – De Dietrich’s 1903 Paris-Madrid contender is Michael Ulrich’s: THE RACE BUGATTI MISSED (Monsenstein & Vannerat, Muenster 2005; ISBN 3-86582-085-9).

Dick,

Thanks for the note. I’m looking for a copy of that book now. Seems that we might have been repeating old errors, and we’d surely like to correct them!

Pete