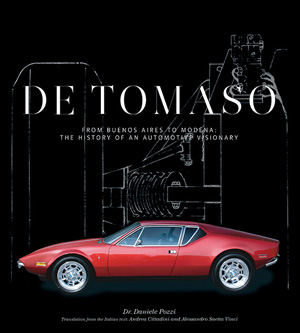

DE TOMASO From Buenos Aires to Modena: The History of a Visionary in the Automobile Industry

DE TOMASO From Buenos Aires to Modena: The History of a Visionary in the Automobile Industry

By Dr. Daniele Pozzi

Translation from the Italian text by Andrea Cittadini and Alessandro Saettta Vinci

280mm x 310mm

240 pages

Over 200 images (drawings, historical photos, photos of car models)

Now Available!

Dalton Watson Fine Books 2015

Our Price: $79.00

Shipping Costs: FREE SHIPPING TO USA AND UK. Shipping to all other countries will be charged one flat rate for first item, additional books in the same order are shipped for no additional s/h charge.

Review by Pete Vack

All photos from the book and used with permission

This is a review of the latest book published about the De Tomaso legacy. There are only a few good books about De Tomaso and this is one of them; nicely packaged, well done and priced right at only $79.00 including shipping to U.S. and the U.K. And we can recommend it; there are a few mistakes, a couple of clumsy translated sentences but not anything to complain about aside from perhaps the unwieldy size of 11 by 12 inches and lack of notes, bibliography and index (all too common today). Anyone who owns any of the myriad of De Tomaso cars will want to add this book to their meager collection. So, there is no need to read the below review, just click here and get it while they last.

However, if you want to know why, despite this promising new book, we still know next to nothing about the successes and failures of one of the most enigmatic, dynamic, romantic motoring alliances in history, then continue.

The lives of Haskell and de Tomaso are no doubt worthy of examination and study. In 1991 Wallace Wyss wrote a book on De Tomaso, but it was not the last word on the subject.

Therefore when the new book from Dalton Watson, “De Tomaso From Buenos Aires to Modena: The history of an automotive visionary” was recently published, we hoped for a singular, definitive book on the subject of the De Tomaso family and fortunes.

While the origins of the Mangusta design may still be in question, there is no doubt the book displays excellent photography by Gio Martorana of the gold prototype Mangusta.

The original text is by Dr. Daniele Pozzi, who is a Professor of Economics at the University of Cattaneo. So the credentials were on hand for a scholarly work with a great deal of research, first person interviews as well as secondary sources of information. For the Dalton Edition, the text was translated by Andrea Cittadini and Alessandro Saetta Vinci, and is very well done. The format is large at 280 cm by 310mm with 240 pages and 220 illustrations, and the quality is up to the exacting standards of Dalton Watson.

In the introduction, Pozzi states his goals for the book. “There was a unique vision for this book because the cars of de Tomaso had to be seen in a new and wider perspective. This is why a historian who specializes in the economic and social impact of companies and a photographer interested in sheer beauty rather than clinical technique have been chosen to produce it.”

And true to his foreword, Pozzi and photographer Gio Martorana do exactly that. But between the pages of beautiful photos of selected De Tomaso cars, there is a wealth of information and a general history of the firm and many business deals of Alessandro de Tomaso.

De Tomaso matured as a race car constructor and automobile manufacturer in the early 1970s, seen here at a press conference with the new F1 car and driver Piers Courage. The Mangusta would soon follow, but the F1 venture did not succeed and Courage lost his life at Zandvoort.

Much of the book is devoted to the years between 1970 and 1993. Pozzi expertly takes the reader through the very complex, difficult and confusing era that ranged from the introduction of the Pantera to the final days when de Tomaso negotiated the sale of Maserati to Fiat. Pozzi well understands the many forces that were at play in Italy (and the U.S.) in those years. He explains the relationship between Ford, Iacocca, Ghia, Vignale and De Tomaso. He discusses in some depth de Tomaso’s attempts to save both Benelli and Moto Guzzi at a time when sales of motorcycle were falling and the Japanese were producing superior goods. Pozzi also relates the industrial strife caused by both the unions and the oil crisis of the 1970s and how it affected the many companies de Tomaso had purchased (often for next nothing). There was so much going on at so many levels and yet de Tomaso, perhaps because he was adept at dealing with multiple projects, saved a lot of jobs for Italy, even though he was forced to lay off workers from time to time. The last minute creation of the Maserati Bi Turbo (the rush would soon cause quality issues) literally saved Maserati (and Innocenti) and allowed it to live another ten years until Fiat took over the marque. Santiago de Tomaso reveals that in the early 1980s, Lee Iacocca, de Tomaso and Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs Giulio Andreotti once met to discuss a deal for Chrysler to buy engines from Fiat or Alfa Romeo. It did not pan out, but ironically anticipated the eventual sale of Chrysler to Fiat.

The Dynamic Duo

Pozzi’s focus is not the history of the de Tomaso family and we must take that into consideration. However, there are new interviews with Isabelle Haskell de Tomaso, Tom Tjaarda, Gianfranco Berni and son Santiago de Tomaso.

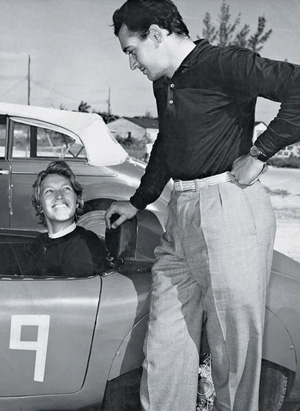

In some ways, the marriage of Isabelle Haskell and Alessandro De Tomaso reflected the industrial marriage of Ford and De Tomaso, and later Chrysler and Maserati.

In some ways, the marriage of Isabelle Haskell and Alessandro De Tomaso reflected the industrial marriage of Ford and De Tomaso, and later Chrysler and Maserati.

Isabelle and de Tomaso, from the book.

This strange, exotic, unlikely pairing played up the long tall, attractive American heiress with the dark, mercurial but often brilliant Argentinian. But perhaps their marriage on March 9, 1957 was more like a business arrangement. In a caption to the wedding photo in the family album, Isabelle wrote the words “The company was founded on March 9, 1957.” Hmm, what could this have meant?

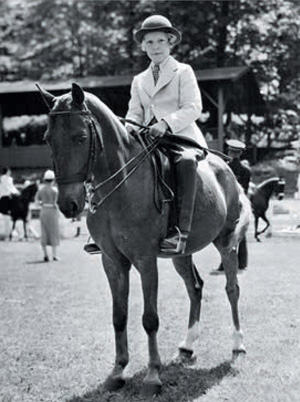

Yet unlike the automotive marriages between Ford, Chrysler and a variety of Italian companies, amazingly the union lasted until the death of Alessandro in 2003 at the age of 74. As of this writing, Elizabeth Isabelle Haskell de Tomaso is still alive and well in Red Bank, New Jersey, tending to her beloved horses and dogs.

Pozzi, thanks to some interviews and a few unpublished photos from the family, provides just enough information to whet the interest for both Alessandro and Isabelle. Both led fascinating, dangerous, privileged yet often difficult lives.

De Tomaso in Argentina

Half Spanish half Italian, de Tomaso was not born into Italy’s motor valley. He was literally a foreigner, not from Bologna, Modena, Milan or Turin but born to a wealthy and politically active family in Buenos Aires in 1928. De Tomaso worked at a variety of jobs including a gaucho or cowboy on the family ranch. His interest in cars came after the war. A photo provided by the de Tomaso family to author Pozzi shows a young de Tomaso sitting behind the wheel of a modified Bugatti. The caption reads “De Tomaso in one of his first races in Argentina in the 1940s.” The Bugatti intrigued us. Consulting Bertschi and Iacona’s “Bugattis in Argentina” we find no mention of de Tomaso but we do find the car, a Type 38 Bugatti owned after the war by famous race driver Roberto Mieres and driven in several events around Buenos Aires. It is instantly recognizable because of the MG T-type tail section. De Tomaso is not listed as a driver, however.

The book’s caption reads only that this is de Tomaso during one of his first races in the 1940s. However, the car is a Bugatti Type 38 owned by his friend Roberto Mieres. No confirmation has been found to the effect that de Tomaso actually raced the car.

Another key to de Tomaso’s early attempts at racing came from the book by Wallace Wyss, who relates the story about de Tomaso driving an Alfa for a one lap tryout in 1951 and gaining the nickname “El Insano.” The Alfa owner was Schwelm Cruz, a famous Alfa driver of the era. Again hitting the books and consulting ‘Alfa Romeo Argentina” by the same duo of Bertschi and Iacona, we find that the Alfa Monza 2.3, s/n 2311209 was driven by Schwelm Cruz in several events in 1951 at the Autodromo de Buenos Aires. It is fairly obvious that de Tomaso was hanging in good company, even though he probably did not actually drive in any races.

During that time de Tomaso also married (into another rich family) and had three children (one of which is Santiago). Then in 1955, de Tomaso suddenly left his wife, family and presumably fortune and headed east to Modena where he planned to race a Maserati sports racer with Carlo Tomasi. He met Isabelle Haskell, there to pay the bill on her 150S, having quickly graduated from a Fiat powered Siata to the Maserati. According to Haskell, the one-time Bugatti T38 owner Roberto Mieres was with Alessandro when the couple met at the Maserati factory and actually introduced Isabelle to de Tomaso. It was love at first sight.

Alessandro’s son by his first marriage, Santiago, was instrumental in keeping the firm going after de Tomaso’s untimely stroke in 1993. Here Santiago is seen driving the 1965 F3 car which is in the family collection.

Follow the money

But of course as the legend goes, there was no money on either side. In 1958, Alessandro went to work as a mechanic and or driver at OSCA. Perhaps both, but he was indeed turning out to be a very fast driver and often participated in events with fellow OSCA pilot Colin Davis. After their marriage Isabelle was a driver, pit crew and bookkeeper as the various De Tomaso enterprises took shape. In the rare interview with Haskell, Pozzi quotes her as saying “My family surely didn’t support me on a financial level and that part was difficult. And it got even tougher when we were married and living off the wages from the races.” Pozzi failed to ask how Haskell, when she was an accountant at Embassy Travel, was able to afford a new Maserati 150s.

Or perhaps Pozzi did ask more pointed questions and the answers were not forthcoming. Had he asked her in what year she was born, that may not have been answered either for despite a good search through our books and the Internet, we still have not come up with a birthdate.

Or perhaps Pozzi did ask more pointed questions and the answers were not forthcoming. Had he asked her in what year she was born, that may not have been answered either for despite a good search through our books and the Internet, we still have not come up with a birthdate.

As a youth, Isabelle loved horses. She still does.

She has always been shy, private and unwilling to open her life to anyone and although often helpful, she shares little. There are few if any articles, books or notices about her life; Carl Goodwin did a chapter about her in his excellent book “They Started in MGs” but he did not actually interview her. Her notable driving achievements both in the US and in Europe were ignored by both “Fast Ladies” author Jean-Francois Bouzanquet and Todd McCarthy in “Fast Women”, presumably because they could not find enough information about Haskell to generate copy. Numerous authors and journalists have found access difficult. There is no Wiki page for Isabelle, and even the Wiki entry for Alessandro is only one paragraph. If this is so, it is because that is the way the family wants it.

Cuban kidnapping capers

Pozzi relates the story of de Tomaso’s eyewitness account of Fangio’s kidnapping on the night before the Cuban Grand Prix, but gets the year wrong as 1957 instead of the correct year, 1958. While that may be a typo, Pozzi mentions the role played by de Tomaso during the kidnapping, (he was there and restrained at gunpoint while Fangio was taken) but instead of quoting Alessandro’s well done and detailed police report, he quotes instead one of the actual revolutionaries who wrote of the kidnapping in a 2005 memoir. De Tomaso’s unabridged report and a full account of the kidnapping are found in Joel Finn’s excellent book “Caribbean Capers”. Nor was de Tomaso entered to drive a Maserati 150S in the event as suggested by Pozzi; no 150S Maseratis were entered nor was Alessandro anywhere in the entry list.

Pozzi also wrote that playboy Porfirio Rubirosa died at the age of 40 when his Ferrari 330GT hit a tree. However, a quick check revealed that Rubirosa died on July 5, 1965, at the age of 56, when he crashed his silver Ferrari 250 GT into a tree in the Bois de Boulogne.

And we may never know

There are new interviews with Isabelle Haskell de Tomaso, Tom Tjaarda, Gianfranco Berni and son Santiago de Tomaso. Unfortunately they are all too brief and provide few new insights.

The Deauville was powered by the Ford V8, and designed by Tom Tjaarda. This is a one-off station wagon built for Isabelle and it is still with the family.

Alessandro was not independently wealthy, but was a driver, mechanic, designer (without an engineering degree), idea man, administrator, executive and a very shrewd business man. He reported to no one and no doubt worked as hard or harder than any of his peers. From an immigrant in 1955 Alessandro de Tomaso eventually owned or had control of Maserati, Innocenti and Benelli motorcycles, not to mention his own firm of De Tomaso automobiles, which produced the Vallelunga, Mangusta, Pantera, Deauville and Longcamp, and kept producing cars until 2004. And for him, the end came very unexpectedly with a severe stroke in 1993 which disabled him. Would he have written his memoirs, or asked someone to write a biography or history of his factories and race cars? Perhaps, we’ll never know.

Most of us are familiar with the Vallelunga coupe, but this is the rarely seen Vallelunga sports racer.

De Tomaso did not divulge much personal information about his life, leading to much guessing and conjecture. So Pozzi begins with a tabula rasa which remains a tabula rasa.

So it goes for his cars. No serial numbers (How many Longchamps were built?). No production numbers, not even complete tech specs. Perhaps smartly, Pozzi gives short shrift to the many dead end prototypes and Isis cars De Tomaso produced in the first ten years. Wyss covers most of these and a wild mess it is, from rear-engined OSCAs to Alfa-engined Coopers and everything in between.

The Longchamp was another De Tomaso aimed at the luxury car market. The Tjaarda design could be considered a coupe version of the Deauville to compete with Mercedes.

In the end, we can’t blame Pozzi or others who came before and will come again for not getting the whole story. And this is sad, for it is a great story, with so many battles both won and lost, so much at stake, so much Italian (and American) car history. The blame lies directly with the main characters; they wished to build racing cars and win races, to be the head of major car companies and be factors in the Italian car market. And so they were. But for whatever reasons, they either left little or no trace (factory documents, financial statements, serial number records, sales records, tech info, personal information, letters, diaries, inter office memos, telegrams, etc.) or will not share such information if in fact it does exist.

History is written by scholars whose subjects leave comprehensive details of their lives and accomplishments, good bad or mediocre. For all that the de Tomasos accomplished, which obviously is a lot, apparently they are not concerned about how history will remember them.

Sources

Caribbean Capers, the Cuban Grand Prix races of 1957, 1958, 1960, Joel E. Finn, Racemark, 2010

De Tomaso, the man and the machines, Wallace Wyss, Adler Publishing, 1991

Alfa Romeo Argentina, Bertschi and Iacona, Whitefly, 2005

Bugatti Argentina, Bertschi and Iacona, Whitefly, 2007

Italian Sports Cars, Winston Goodfellow, MBI, 2000

I vaguely remember reading an interview with De Tomaso in one of the popular car magazines back in the early 90s. De Tomaso was asked why he had chosen not to use antilock brakes on the Chrysler TC (relatively new technology back then, but was available on select Chrysler vehicles). His response; “Antilock brakes are for people who don’t know how to drive cars.” Sounds like Enzo and his statement that aerodynamics are for people that don’t know how to build engines. Definitely two men that did things “their way.”

i have a few pix i took while with dick irish visiting detomaso in ’68. one shows a flat-4 engine lying alone on the very clean shop floor. the man showing us around smiled and put his finger to his lips when i took the photo. i wonder what it was to be used for.

@ toly arutunoff

This one ?

http://www.barchetta.cc/All.Ferraris/images/5535/v54564_56452_1963.jpg

source : http://www.finecars.cc/en/editorial/article/news/museo-de-tomaso/index.html