Commentary By Brandes Elitch

Last week (February 7th), two different cars were listed for sale on eBay Motors. While they appear to have nothing in common, these two listings raise some important questions. The first, item 220734001769, was a 1952 Ferrari 212 Pinin Farina coupe. To quote from the listing, “212 body in great condition, mounted on a metal dolly with wheels to roll around…it is unbelievable…you could fit an American engine and chassis and have a half million dollar look at the country club. The chassis and engine was used to build a beautiful 212 Touring- bodied barchetta.”

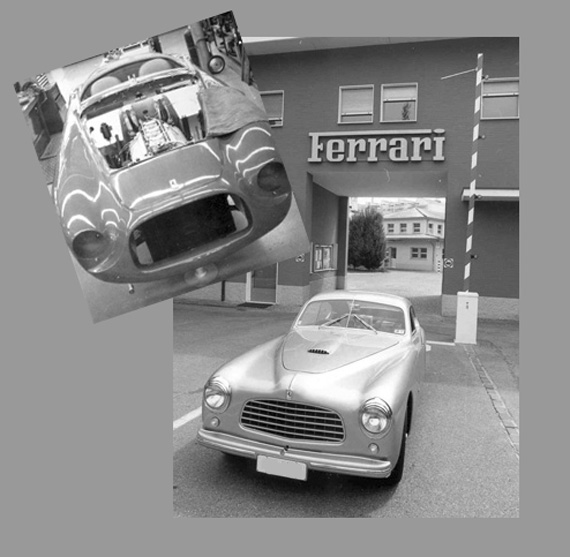

Now, this is no ordinary Ferrari, if indeed there is such a thing. The 212 was an evolution of the 166, fitted with a slightly larger version of the Colombo V12 motor. It is historically important because the 212 series is the first Ferrari designed and built by Pinin Farina. The very first Ferrari with a Pinin Farina body was 0177E, a convertible. Up to then, neither man would approach the other to solicit working together; a meeting was negotiated halfway between Maranello and Torino so that they could come to an agreement. The 212 was in production for only 2 years, and eighteen were constructed with bodies by Pinin Farina. Of course, the early Ferraris are the most desirable, perhaps not to a poseur, but to a real collector.

I was curious about how such a thing could come to be, and so I asked the most authoritative source in the US on Ferrari history, Mike Sheehan. The car was originally sold in Florence, then went to Australia, and then, from 1956-1989 was in New York City. In 1990, it was listed in the Ferrari Market Letter (FML) for $385k. Four years later it was relisted for $225k by the same seller, with a 250 GT Boano motor. In 1997, it was listed at another auction, and not sold at $81k. In 1998 it was sold to DK Engineering, in England, and in 2000 Brian Classic is listed as the owner. In 2005 it was reported that it was rebodied as a barchetta. In 2009, the barchetta is sold for $440k at auction. Finally, the most recent information states: “The engine from s/n 0259 EU is with s/n 0112 E as a spare. The chassis has a fake barchetta body and Boano engine #0553.”

Now, put this aside for a moment, and let’s consider another listing, a Delage D8, one of the greatest cars of the classic era. There was quite a story connected with the listing, implying that the owner found the car, seemed somewhat unfamiliar with what it really was, but acquired it and towed it home with his Saab. The tantalizing picture of this magnificent vehicle on the web shows it sitting forlornly in the side yard, covered with snow. It appeared to be a very unlikely story, the Delage in the barn, except for one thing: the price. It was offered on eBay for one million dollars. But then, a strange thing happened. Comments started appearing on the web that things were not as they seemed. Quickly, the seller cancelled the original ad, and then posted a second ad, with a price of $750k. He stated in the second ad that “now he has had his fun,” and that the original listing was a hoax.

I have researched this story, and concluded that it wasn’t just the ad that was a hoax. The seller stated that the original body was scrapped because it was beyond any hope of repair. Members of the Delage Club in England, and the British Register, created by Peter Jacobs, have a different story, with pictures to prove that this is not true. It turns out that this seller also broke another very sound and totally original Delage D6/70 (s/n 51540) in New Zealand, to fit a counterfeit body. I wonder what would have happened with this listing if the Internet audience had not revealed the true story? After reading two of these stories in one week, you might be tempted to ask, “What is going on here?” Or, to quote William Bendix, “What a revoltin’ development this turned out to be!”

Let me make a couple of points, and then you can draw your own conclusion. First, this is about money, big money. It is not about saving a car from being parted out or creating a car out of a bare chassis. Second, the Classic Car Club of America addressed this issue early on, and concluded that while it is perfectly acceptable to rebody a car in a completely authentic and historically correct manner, it has to be the original body, not cutting up a sedan to make a Boy Racer, a common practice amongst the Bentley Drivers Club, or cutting up a Cord 810 sedan to make a coupe, something that the factory never made in the first place. Last month, the CCCA had their annual meeting in Palm Beach, and the attendees were treated to a tour of a private collection in Boca Raton. The owners had replicated not just a car, but a seemingly accurate copy of the front of the ACD Administration building (now a museum), even bringing back the correct stone from Indiana for the façade. I was stunned. Inside were two circa 1934 Cadillac V-16 cars with spectacular coachwork. Actually, they were new bodies constructed by Cadillac “restorer” Fran Roxas. In this case, the story we heard was that they were built from coachbuilders sketches made around 1934, sketches that were never translated into a real car in the first place, until now. Yeah, right.

Many examples abound. When the Ferrari GTO was featured at the Monterey Historic weekend, I heard someone comment, “Of the original 39 cars made, all 45 are here this weekend!”

Now you might say that this is not so bad, because a more desirable car has taken the place of something which was sacrificed. But what was sacrificed? The answer is: honesty, authenticity, and originality, the very essence of what makes antiques and works of art collectible in the first place. Should a “restorer” touch up an Old Master painting because he thinks he can “improve” it, or make it more desirable? Of course not. Now you might ask, “What about hot-rods?” Look, it’s not the same thing. These cars (the great majority of which are T, A, B, or late thirties Fords) were made to a price in massive volumes. At one time, there was a Model T, Model A, or Model B Ford on every block in the country. How can you compare this to a 212 Ferrari, particularly given that each and every single one of the 82 cars had a custom body made by hand out of sheets of aluminum, and a handmade, custom interior? The answer is obvious: you can’t.

Automobile restoration is first and foremost about preservation, not fakery. But just to show that all is not black and white, here are two examples. First, take a look at the modern replica C-type and D-type Jaguars being turned out in England. These cars are titled as new cars, and indeed they are. They use authentic Jaguar running gear, and original cars are not sacrificed to make them. I’ve seen a few at the Essen Techno Classica show, and they look about as close to the real thing as I can imagine. As long as they are not misrepresented, why not? The second example pertains to what happened when Maserati withdrew from F1 racing. A British restorer bought up all the spare 250F parts from the factory, and he had almost enough to make a handful of additional cars, which he did, being careful to always reveal their real provenance. In this case, we should be grateful that this happened. But we should not be so quick to admire fakery, no matter how well it is done.

Fortunately, resources are available to help make an informed decision. Many single marque clubs, like the Delage Club of England, have club historians or members who can provide details about the previous history of a car. The CCCA has specialists in most marques that they recognize as “Classic,” a term they have trademarked. And when it comes to Ferraris, there is one place to go: Mike Sheehan. All you have to do it to click on: www.ferraris-online.com / to subscribe – it’s free. Thanks, Mike. As they say in nuclear arms negotiation, “Trust, but verify.”

Excellent story, except that you should have given credit to the web site where widespread attention was first brought to both the Ferrari and the De Lage, and which hosted many of the comments which outed both cars for what they were:

www. bringatrailer.com

Very good article shedding some light on a negative aspect of our car hobby. I have been around the car hobby since the 1950’s and have encountered many shady characters not averse to bending the truth and some in my own family. I have followed the examples that you cite during their travels in the internet and was glad to see them get some exposure. This behavior is not unique to the collecting of cars, but rears it’s head in most any upper end collecting hobby. I hope the marque clubs can expose as much as possible about this lying and fakery. It casts a cloud over all of us.

Randy Reed

Thanks Brandes. I too followed the story on bringatrailer.com and it looks like this time the good guys won. I’m sure there will be more trickery in the future given the piles of cash some of these historic vehicles trade for. We must always be vigilant.

It’s not the modifying that is irritating – an owner can do whatever he wants with his car – it is the misrepresentation.

So now what do you do with these cars (or half of a car, or whatever)?

Here is the translation, courtesy Brandes Elitch–Ed.

“This is a subject that people feel passionately about, and the author has

done a good job of segmenting the discussion in 3 categories. What I hope

to add, as much as it is practical, is to put things in perspective for the

time when these cars were new. To better understand, we have to remember

that when cars were new (up to around 1935), people had custom bodies built

for special cars, and kept a car for ten years or so. After a few years,

cars were “modernized” with some changes, or even completely re-bodied, even

going so far as to convert a coupe to a cabriolet. Even racing cars were

subject to this kind of transformation. For example, when rules required

that the fenders meet the hood, around 1951, most of the Talbot GP cars were

rebodied, some by Motto. Certain Bugatti type 57 cars were also rebodied,

at least one Atalante, which was accessorized with chrome accents, in the

period 1937-9. Many single seater racecars were converted to coupe or

roadster bodies between 1945-55, but lack of funds made this contingent on

getting tires and fuel, which made them seem new for another 3 years.

Sometimes, the factory contributed to the confusion; we know that Ferrari

allowed replica cars to be produced, under his name, for ten years, before

finally seeking legal injunctions. And then, the press reported a few years

ago that Caroll Shelby still had a few untitled Cobra chassis which he

wished to use to produce another run of cars. Another category is the

re-construction of very limited production cars (say 2-4 cars produced)

where the originals no longer exist, for example the 1923 ACF de Tours

Voisin GP car, the Matra MS 680 driven by Pescarolo which was destroyed in

an accident, the unique AC Cobra coupe, and several others. But now we have

arrived at the construction from scratch of cars that were never made in the

first place. One example is, after 30 years, an Aston Martin DB4S

cabriolet. Or what about the small series of Ferrari Daytona cabriolets

that Luigi Chinetti made by cutting up the factory coupes? In these two

cases, I didn’t personally verify if these cars were made by the factory.”

Here comes the nit-picker: The untitled Cobra 427 Cobra chassis that you allude that Carroll Shelby had have pretty much

been described as being from a more modern era (i.e. not from the 1960s when he was originally producing cars as Shelby-American on Imperial Highway) in expose articles by Paul Dean

in the Los Angeles Times. I would describe them more as replicas. The Ferraris that Chinetti ordered made into spyders from coupes were 275GTB/4s, called “NART” spyders. Although not regular Ferrari “catalog” models they have soared in value and are now worth more than the coupes they sprang from, especially when there is a famous name to be found in the owner list, such as Steve McQueen.