By Pete Vack

Or, get it from don@bugattibooks.com, 941-727-8667.

Bilingual

English

Français

Format 240 x 290 mm

Pages 416

ISBN 978-2-8151-0611-5

€150.00

Literally, the Roaring Twenties

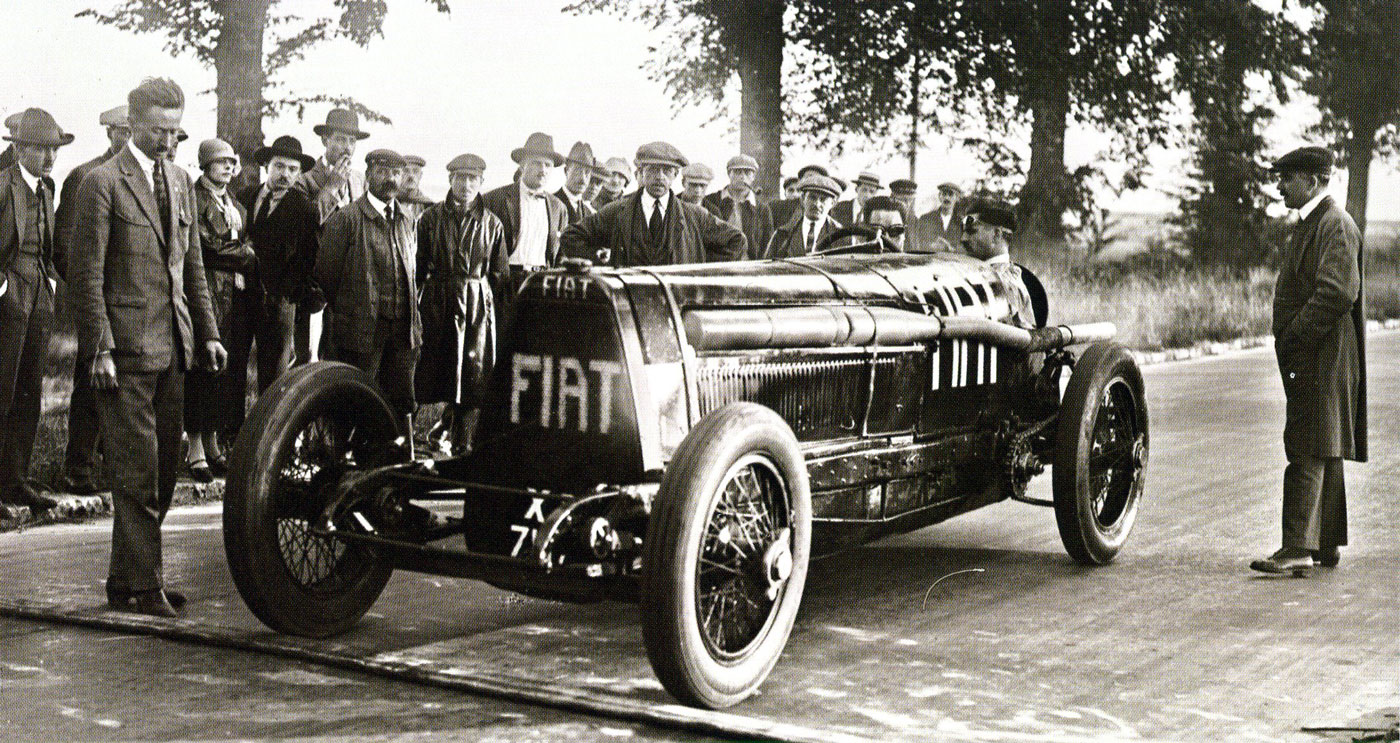

In the past few weeks, we have been re publishing a series of articles by Gijsbert-Paul Berk about the epic 1923 French Grand Prix at Tours. His excellent coverage highlights this era which saw the introduction of supercharging, streamlining, the dominance of the DOHC engine and the participation of factory teams from Delage, Sunbeam, Fiat, Bugatti, Voisin and Rolland-Pilain.

It was an exciting, vibrant era of major technical achievements that is often ignored. Perhaps one reason was that the twenties were a confusing time in Grand Prix history. To better understand Daniel Cabart/Sébastian Faurés’ excellent work as reviewed here, let’s take a look at the development of Grand Prix racing in the 1920s:

*From 1914 through 1920, there was no top echelon racing in Europe (racing continued in the U.S.).

*The 1921 season was run to a 3 liter formula, which saw the Duesenberg win at Le Mans.

*For 1922 through 1925, the Grand Prix de l’ACF reduced the displacement limits from 3 liters to 2 liters, with a minimum weight of 650 KG and two seats. It saw competition between Fiat, Sunbeam, Delage, Alfa Romeo and Bugatti.

*For the 1926 to 1927 seasons, the limit was reduced to 1.5 liters supercharged and was dominated by the Delage 15S 8.

*1928 through 1933 were the years of the Formula Libre, during which Bugatti and Alfa won many races.

Despite the few official Grand Prix events (nothing like the 22 or so we have today!) the factory entries were in a hot horsepower race. In only six years Grand Prix car horsepower doubled, and this even after a loss of 500 cc (but increased supercharging) as the 2 liter limit was reduced to 1500 cc.

Into this amazing arena stepped Louis Delage, confident that his designers, engineers and drivers could compete with his lofty rivals. Delage re-entered racing in the early twenties and retired his cars in 1928 as world champions. It was not easy nor always successful, but a great ride, which makes a great book.

Cabat has previously written about Delage; with Claude Rouxel he wrote Delage, la belle voiture française (ETAI 2005), later translated by David Burgess Wise under the title Delage, France’s Finest Car published by Dalton Watson; in 2017, along with Christophe Pund, Cabart completed Delage, Champion du Monde, which focused on the 1926-1928 Grand Prix seasons and the all-conquering Delage straight eight Grand Prix car. Sébastien Faures, on his side, has been the author of Fiat en Grand prix (ETAI 2009) and Lorraine-Dietrich (ETAI 2017). Last year, co-writing with Sébastien Faurès Fustel de Coulanges, Cabart brought to press Delage, Records and Grand Prix, illuminating the racing and record cars built from 1922 to 1925 as reviewed here.

“Our latest book is the result of my nearly 40 years of collecting pictures, archives, researches in period press aimed at paying tribute to this exceptional man: Louis Delâge,” wrote Cabart. But the team of Cabart and Faures has proven very effective. According to Cabart, “Although about 90% of the material came from my archives, the writing is really a ‘four-hands’ writing. Faure’s cleverness and engineering knowledge has been absolutely essential to the quality of this book, mainly regarding the mechanical aspect of the text.”

Another Landmark Book

Although limited to a discussion of Delages in competition, this latest book is one of the most important of the most recent books about this fascinating era. In a comprehensive and interesting fashion, the authors write of the drivers, owners, designers, mechanics associated with Delage, and then illustrates the text with outstanding photos from each event. There are engine diagrams, full explanations of the modifications and operation, charts and graphs as well. It is in depth, covering not only the Grand Prix cars but the sports and record cars built and raced in the 1922-1927 timeframe.

By his own account, Cabart’s three books rank alongside Grand Prix Bugatti (Conway), Sunbeam Racing Cars 1910-1930 (Anthony S. Heal), Fiat en Grand Prix 1920-1930 (Sébastien Faurès Fustel de Coulanges), and The Magnificent Monopostos- Alfa Romeo Grand Prix Cars 1923-1951 (Simon Moore). Cabart’s efforts have certainly shed light on the significant accomplishments of Delage both on and off the track. It need not be said that if you have any of the above books, you will both enjoy and need all of Cabart’s works.

Delage, Records and Grand Prix is part of a trilogy and therefore on its own is not easy to understand without having read at least France’s Finest Car, which covers the same ground but provides the big picture. We found ourselves refreshing our knowledge of both Delage and the races of the era via Cabart’s first book. If France’s Finest Car can’t be obtained, a relatively complete history with plenty of useful charts and lists can be found in Automobile Quarterly V14 2 from the second quarter of 1976. Here, Griff Borgeson’s study takes up half of the edition. Borgeson used many of the same sources as does Cabart, but conducted many relevant interviews with principals who were still alive at the time. It makes up in clarity what it lacks in depth.

Delage was a great marque well before WWI and was very successful on the track. After being founded in 1906, a year later a Delage finished second in the Coupe de Voiturettes, then winning the 1908 Grand Prix des Voiturettes. The Delage type Y won the French Grand Prix in 1913, and to top it off won the 1914 Indianapolis 500, René Thomas’ greatest win. A return to racing was eagerly anticipated. After WWI, Louis Delage wanted to make sure that his company prospered during the postwar boom. His lineup of cars seemed to cover the market, and the company prospered. Delage had always supported racing and continued to do so throughout the twenties. At the same time there was a plethora of models and engines emanating from the Delage camp from four cylinder sidevalve units to DOHC sixes and the ultimate Delage engine, the 2LCV 2 liter DOHC V12, at the time the smallest V12 ever built. Cabart and Faures’ latest book serves up only the competition cars built between 1922 and 1925 in depth.

In addition to René Thomas, who served as a driver and team manager, the authors tell us the story of Delage’s chief designer, Charles Planchon. As we can see from the list below, Planchon was very busy and very creative in his two years with Delage until he got fired (the authors squelch the oft-repeated statement that Planchon was a cousin of Delage). Albert Lory took over and refined the V12 into its championship form as well as penned the 15 S 8.

A list of the basic competition cars/engines and their designers as covered by the book:

1922 DE 2.1 Liter four, sidevalve, Charles Planchon

1922 GS 5.1 liter six, with special 6F head. Toutée, Michelat

1922 DF 2 seat racecar, used GS six cylinder with 6 F head

1922 DG 4 seat racecar, DF six tested in wind tunnel

1922 2LC 2 liter Grand Prix car, four cylinder, SOHC?, Planchon

1922 2LS (Sport) four cylinder with a 6F type head

1923 GLGS Gran Sport, DOHC six Planchon

1923 DH 10.7 V12 pushrod, record car, Planchon

1923 2LCV 2 liter DOHC V12, Grand Prix racer, Planchon, Albert Lory

Organization

Logically, the book is in chronological order, which after a brief review of the pre war Delage race cars and a chapter on René Thomas and Charles Planchon, begins with the 1922 racing season and discusses the origins of the various race cars, the GS, DF, DG and 2LC, and the races in which they participated. And since those cars continued to be competitive in non-championship events from 1925 on, the book covers the years from 1925 to 1928 as well. But the Championship years of 1926 and 1927 with the 1500 cc straight eight is not included, being the subject of the earlier book. Could it have been arranged in a more helpful fashion? Perhaps, but given the wide subject matter and multiple designs, probably not. There is simply a great deal of information to impart, from race reports to record runs to Grand Prix races, drivers, and engine specs. However, there is a good bibliography, footnotes, and a decent index. Rare for this type of work, a chapter at the end of the book reveals what happened to the cars and where they are today, if known.

We would be remiss if we did not mention the excellent translation to English by Reg Winstone. Complimenting this translation is the layout work of Sophie Jauneau, who has already produced the previous Delage, Champion du monde. Unlike many bilingual books, the French and English texts are paged opposite, with French on one page and the English on the other, without overruns or page confusion. Most remarkable! Photo selection and reproduction are also outstanding.

If, as we are, you are a fan of that era, have an abiding interest in the development of the Grand Prix car, or are a French car enthusiast, don’t pass on this book. Prices on these types of histories are high, but a quick look on Google for any of the books mentioned here will reveal that those prices rise significantly, or in some cases, as with Simon Moore’s The Magnificent Monopostos, the books can’t be found at any price.

Delage in the 1920s: Numerous engines, multiple chassis, many classes

Grand Prix

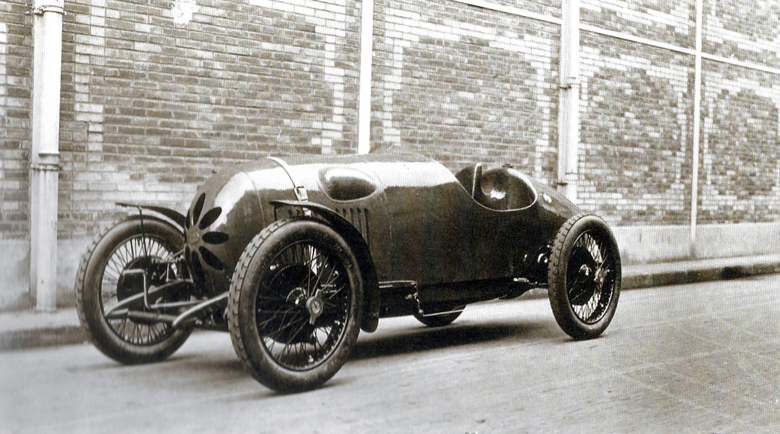

A two liter four cylinder engine powered this 1922 Delage 2LC, built for the French Grand Prix. Though not successful, it led to the development of some of the fastest and most complex Grand Prix cars of the era.

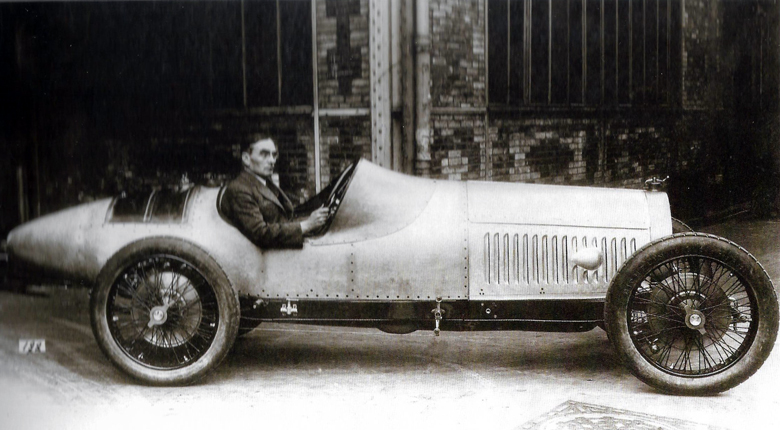

Engineer Charles Planchon with the first iteration of the Delage DOHC two liter V12. The 2LCV was a mechanical masterpiece and the smallest DOHC V12 built to that date.

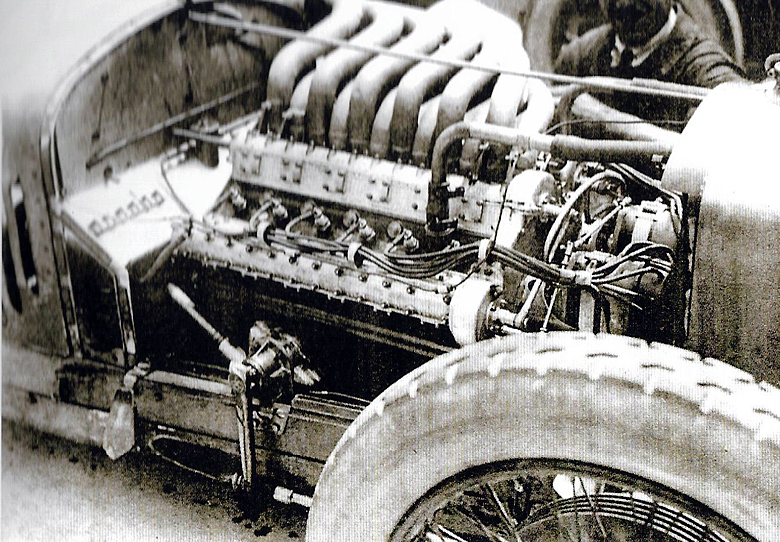

The combined talents of Planchon and Albert Lory were responsible for the 1925 supercharged V12 Delage. The complexity of the engine is obvious, and yet the twin superchargers are hidden from view, beneath the magnetos.

The Land Speed Record

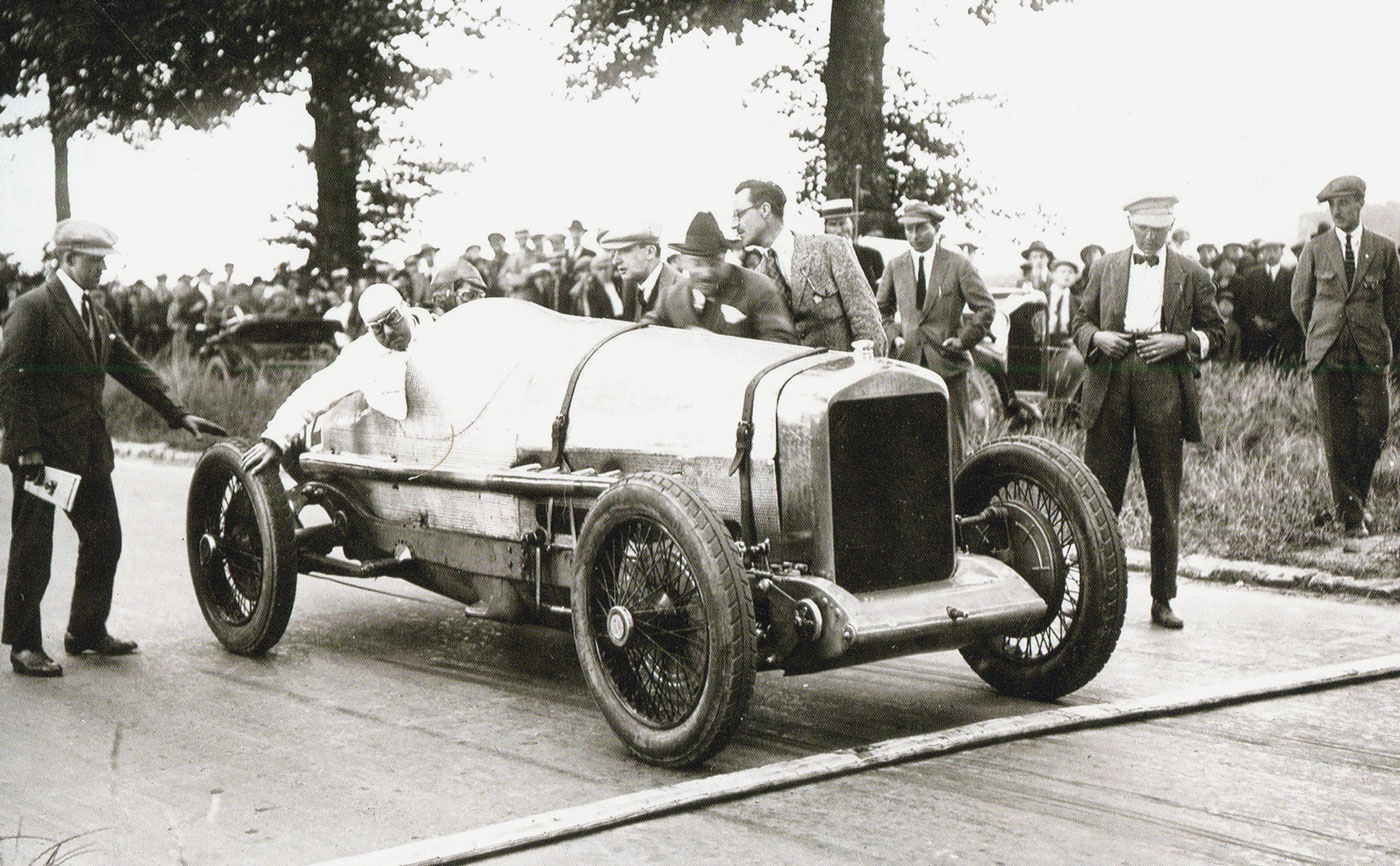

But may forget that at Arpajon, France, on July 6th, 1924, the Land Speed Record went to the huge V12 Delage. Thomas is beginning his record run of 230.634 km/h.

Hillclimbs and speed events

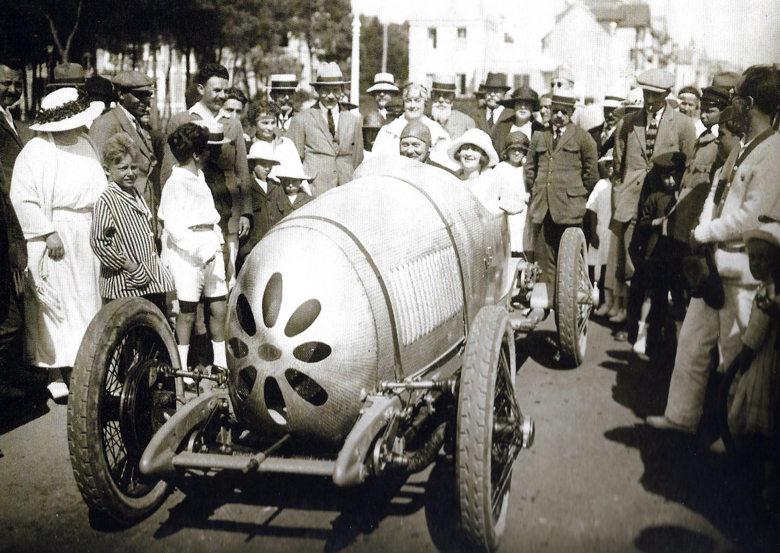

One of the most successful of all Delage race cars was the DF, here seen winning its class at a speed meet at the beach in La Baule, August, 1922.

Dear Pete :

A glorious work indeed ! Please note the book is available this side of the pond from yours truly. Perspicacious enthusiasts should contact me via email at

don@bugattibooks.com or 941-727-8667.

All best, Don