Franco-American Love Story

By Philippe Defechereux © 2008

To read Part I, click here.

To read Part III, click here.

Our tale of the extraordinary love affair between a small French car maker, Deutsch-Bonnet, and an American father-son pair, tied to the birth and future success of the Sebring Twelve-Hours, continues in this issue.

We now tell the story of the unusual, challenging and politically-charged circumstances under which the first Twelve Hours were run, the sparkling success of this great dare; then the first life of the Deutsch-Bonnet HBR5 Cotard Coupé, which originally raced at Sebring in 1959, only to be left “mummified†in a wooden sarcophagus in New Jersey for nearly 30 years starting in 1963.

Deutsch-Bonnet HBR5, chassis #1057 at the Le Mans Vintage 24 Hours event in 2002. Powerplant is race-tuned Panhard flat twin 850cc engine. Skip Cook at the wheel. Photo © J-E Descombes (www.sportmeca.com).

Once the deal between Sebring and Deutsch-Bonnet was sealed in late 1951, Bill Cook could play his other trump card. The Grumman test pilot and racing aficionado was also a master at public relations; this would prove critical for the Sebring race, now scheduled by the FIA on their international calendar for March 15, 1952. Indeed, to quote Alec Ulmann: “We set out to beat the drums early in the year. Bill Cook rendered great help in getting the publicity of the Race started in the New York papers.

Alec Ulmann and Bill Cook shake hands over a D.B. which had just arrived in New York. Photo courtesy of Edward Ulmann.

Deutsch-Bonnet and Sebring Become Big Winners

“When the two Deutsch-Bonnet cars arrived on the [liner] Ile de France, he and I met the boat and were photographed while the cars were unloaded. This made the News and the Mirror and Cholly Knickerbocker had a few quips in the Mirror about the great International Society Event which was to take place in Florida.” [John] Perona’s El Morocco became the social center of the race, as he proudly displayed the first Sebring poster, showing the “Noon to Midnight” motif. These were the chosen times for start and finish.

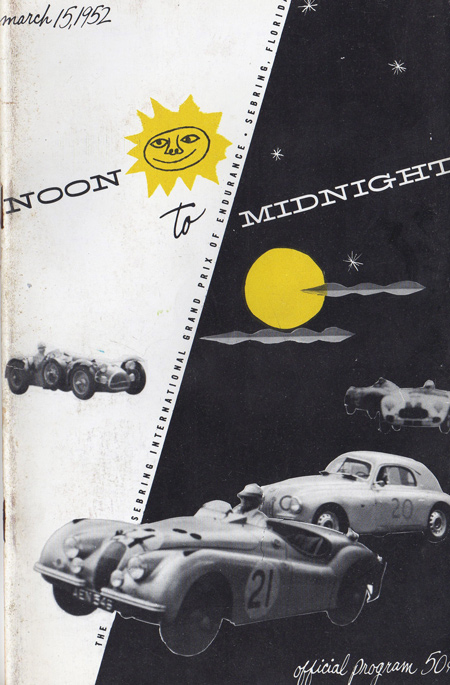

Original cover of the first Sebring Twelve Hours (1952).

Courtesy Edward Ulmann.

The first Twelve Hours of Sebring race was held as planned on March 15, 1952. For perspective, this was a mere two years after the International Grand Prix (Formula 1) Championship was first established. Unlike the inaugural race, this event would be run under the same rules as Le Mans: the overall winner would gain victory on overall distance.

The Index of Performance would also be a highlight with rich rewards. When the green flag was dropped, 32 participating cars were lined up, Le Mans style, along the start/finish straight. There were Ferraris, Jaguars, Frazer-Nashes and, of course, several MGs.

The start of the 1952 Twelve-Hour Race. A field not exactly like Le Mans, yet. Courtesy Edward Ulmann..

Among these were the D.B. barquettes number 24 to be driven by Bill Cook and René Bonnet and the number 25 to be driven by Wade Morehouse and Steve Lansing, both from the New York region. Morehouse, a mechanical engineer for Fairchild Aircraft in Long Island, was a close friend of Bill Cook’s. The race was hard-fought. About mid-way, the D.B. number 24 developed a clutch problem and was disqualified in the pits on a technicality. Bill Cook, always publicity conscious, reassigned René Bonnet to be co-driver of the number 25 D.B. barquette.

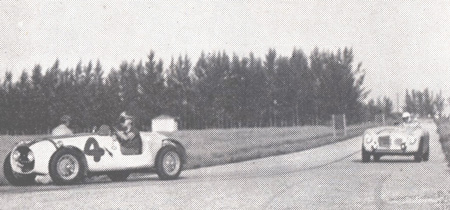

The M.G. Special of David Ash, co-driven by John van Driel, leads a Siata roadster. They finished 6th. Courtesy Edward Ulmann

By the end of the twelve hours, a two-liter Frazer-Nash driven by Larry Kulok and Harry Gray had beaten the rest of the field, including a competitive 3.5 liter Jaguar, to take overall victory. Most important to Alec Ulmann and Bill Cook, the remaining D.B. had finished seventh overall and won the Index of Performance.

Deutsch-Bonnet barquette at Sebring, 1952. Wade Morehouse at the wheel. That is the car that won the Index of Performance and helped change racing history in America. Justwood photos.

This proved to be the most critical item for Sebring’s future. Alec Ulmann again: “The Deutsch-Bonnet victory, though not exactly front-page caliber in the U.S., created a furor in Europe and, especially, France.” Said the conservative newspaper L’Equipe, “René Bonnet and his D. B. Panhard are the best ambassadors for the French automobile industry.” In addtion, Marshall, Solex and Dunlop took full pages of advertising to announce their win.

The D.B. barquette number 24 in the pits. Hobart Cook standing by. The car dnf’d. Courtesy Edward Ulmann.

Wade Morehouse, interviewed from his home in Oakland, CA for this article, remembers the exhaustion and exhilaration of the finish as if it had happened the day before: “I was very close to the Cook family and both Bill and I had bought an MG TC from the same Long Island dealer. I wanted to do well at Sebring as it was so important to Bill.

“Steve Lansing started the race with a short stint, then I took the wheel for about five hours, until I was relieved by René Bonnet. I drove the last two hours in great discomfort; leaded gas vapors were leaking into the cockpit and I was suffering from some sort of lead poisoning. When I crossed the finish line and realized we had won the Index, I felt an memorable mixture of wild joy and great pain.â€

The Ehrman/Wilder 2088cc Morgan leads the Morehouse/Lansing D.B. into a turn. The D.B. would finish 7th overall, two places ahead of the Morgan, despite an engine displacement of only about a third the size (745cc). Sebring Archives.

The cast was set. In 1953, the Sebring Twelve Hours were officially sponsored by Shell Oil and became an official event in the FIA list of endurance races counting for the world championship. A major European team, Aston Martin, decided to participate. The American Le Mans tested Cunningham team would also be there. In total, there were 63 entries, including two more D.B.’s aiming for the Index of Performance. Sebring was now almost on a par with famous endurance races such as Le Mans, the Targa Florio, the Mille Miglia, or the Tourist Trophy. This instantly made the SCCA look very small. Alec Ulmann, Bill Cook and their friends had made the impossible happen.

Deutsch-Bonnet victory celebration at Sebring 1952. From left to right are Hobart “Bill†Cook, Wade Morehouse, René Bonnet (behind the trophy), René’s wife Billy, René’s brother and their French mechanic. Courtesy Edward Ulmann.

A Cunningham C4R driven by John Fitch and Phil Walters won the race. Again, the D.B. driven by Bonnet-Morehouse won the Index of Performance. Bill Cook was still the team’s major sponsor. The Aston Martin team did well, but not well enough. They would come back, along with all the most famous teams of the next fifty years. To this day, the Twelve Hours of Sebring are still a major international racing event.

D.B. HBR5, Chassis #1057 – First Life

By the end of 1958, Deutsch-Bonnet racers had accumulated both a large number of fans and a collection of great victories; besides the 1952 and 1953 wins in Florida, they had won the Index of Performance at Le Mans and the Tourist Trophy in 1954; The Tourist Trophy again in 1955; Le Mans again in 1956.

Deutsch-Bonnet barquette that raced at Le Mans in 1958 and finished 12th overall driven by Laureau/Cornet. Courtesy Mr. Vincent diPierro.

The marque’s reputation was splendid; business was good and new models, barquettes or coupes, kept rolling off the little factory, all superbly streamlined by Charles Deutsch. By 1957, the two partners decided a thoroughly new model was warranted, with only the Panhard engine remaining a constant. This new Deutsch-Bonnet became known as the HBR5 and would prove to be the company’s most successful model ever. It was a coupe fiberglass body anchored to a central tube chassis with the front suspension featuring a double transverse leaf spring and shock absorbers, while the rear suspension had a strut and trailing arms design with telescopic shock absorbers.

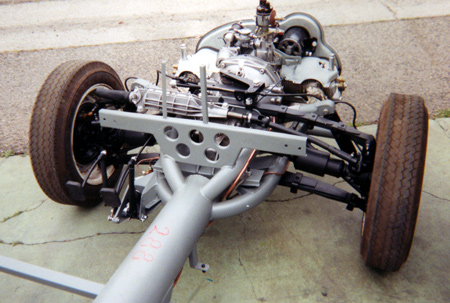

Deutsch-Bonnet HBR5 (chassis 1057) front suspension and engine details. Courtesy Arthur B. Cook..

The Panhard twin-cylinder boxer engine could be a 750cc or an 850cc version, depending on the owner’s wishes or race circuit characteristics. A total of 420 HBR5’s would eventually be built, all but five with a fiberglass body built by Chausson, then the largest car body maker in France.

Road & Track, in an article featured in their December, 1957 issue, said: “Summed up, the 851cc Deutsch-Bonnet coupe is a well-made, comfortable car which can readily be used as a dual-purpose machine. … the competitive-minded driver is virtually assured of a trophy in class H production. And where else these days can you ‘buy’ a few trophies for so little?†The stated U.S. price in that article was $3,850.

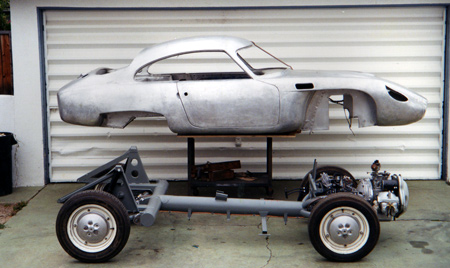

The car that is the central feature of this article, chassis #1057, was built in late 1958 and was one of the only five sporting an aluminum body. Each of those five bodies was designed and made by French carrossier Cotard in Bourg-en-Bresse (eastern France); and had unique minor aerodynamic details of their own. All five, however, followed the overall “fastback coupe†shape and dimensions of the fiberglass-bodied HBR5.

Deutsch-Bonnet HBR5 (chassis 1057) central-beam chassis design and Cotard aluminum body. Courtesy Arthur B. Cook.

The wheelbase measured 7 feet while the dry weight was 1,170 lbs (530 kilos) and, at 7,000 rpm, this small-bore powered car could reach an amazing top speed of 112 mph in overdrive (850cc engine). The D.B. contract with Cotard was originally intended to be a long term affair, but for some reason it was terminated after just five bodies were built. This makes these five cars quite unique.

Howard Hanna of Pennsylvania was the first owner of chassis #1057, which he pre-ordered from Deutsch-Bonnet to be powered by a 850cc engine. He was a D.B. enthusiast and decided to aim for the 1959 SCCA class H championship, starting with the Twelve Hours of Sebring on March 21, 1959. For that race, he teamed up with friend Richard Toland; they both became, officially, part of a three-car “Factory Team,†which also would include two 750cc barquettes to be driven by Paul Armagnac/Gerald Laureau and Bill Wood/H. Derrier. The coupe was assigned racing number 57, the barquettes number 59 and 58, respectively. The main competition for class H would come from Lotus Elites, Fiat Abarths and OSCAs.

Howard Hanna in a Deutsch-Bonnet HBR5 GT coupe with a fiberglass body by Chausson.

As the race proceeded, Hanna/Toland were doing well until lap 82 – just about mid-race – when they were forced to retire. Still, the Armagnac-Laureau barquette did win both its class and the overall Index of Performance. It was another great day for Deutsch-Bonnet fans; Howard Hanna went on to win the 1959 class H championship, while another D.B. team won the Index of Performance at Le Mans yet again that same year. The little factory from Champigny-sur-Marne was now geared up to produce some 15 cars per month, a number unthinkable five years earlier, before the first win at Sebring. The 5.2-mile track was now a famous international venue also; Alec Ulmann and Bill Cook had succeeded beyond their wildest dreams.

Rare photo of D.B. chassis #1057 at Nassau in 1962, one year before it met its demise, never to race again for almost three decades. Courtesy Arthur B.

In late summer of 1960, Howard Hanna sold his aluminum D.B. coupe to an east coast acquaintance, David Darrin. This gentleman from New Jersey raced the car in numerous SCCA events, the last one being the then famed “Nassau Speed Week†of 1963, a series of races run under the tropical sun just when New York and Boston were in the dead of winter getting ready to usher in the New Year.

There, chassis #1057 met its seeming demise. Darrin blew the engine but shipped the car back to New Jersey, trusting it to his long-time mechanic Jay Fisher for possible repairs. Fisher eventually acquired the car and, in an attempt to put it back into racing shape, disassembled it. Either from lack of funds, or interest, or both, Fisher eventually ended with the various parts, from the biggest to the smallest, all packed into crates and cartons. There they stayed for roughly thirty years, until Raymond Milo, a dealer in rare European vintage cars, bought it from Fisher in 1998.

Deutsch-Bonnet HBR5 chassis #1057 just after its death in 1963 due to a blown engine; it would be resurrected almost three decades later. Courtesy Arthur B. Cook.

Now a party interested in buying a bunch of crates containing the randomly arrayed parts of what had by then become an obscure little French racer needed to be found. An automotive journalist of high repute and California connections was going to be the spark for chassis #1057’s second life, proving that reincarnation does happen, at least in the world of automobiles.

Next: Part III. The near-miraculous resurrection D.B. chassis 1057 and its memorable run at the Le Mans Classic in 2002.

Hi Philippe –

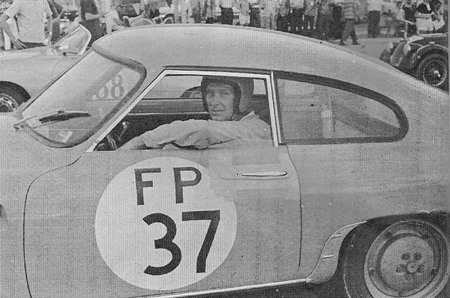

I very much enjoyed your DB articles as I am in process of completing the restoration of HBR-5 Coach chassis #1028. In fact, I have strong reason to believe that my car is that shown with Howard Hanna at the wheel (FP#37) in part 2 of your DB series. Several areas of minor damage to the car in the photo match the “before” condition of my car perfectly. Also, mounted on the rollbar were the remains of a 1961 PA inspection sticker; Hanna was from Philadelphia.

I would love to find out more definative proof that would confirm my car’s early history. If you have some good sources on SCCA east coast race history and/or DBs, I would be very grateful.

Thanks,

Rich

Laguna Beach, CA

Very interesting…I’ve just stumbled upon the three-part DB article. I met Skip Cook very briefly at Watkins Glen when he was shaking down #1057…I didn’t know that it was originally my dad’s car. (My dad was East Coast distributor of DBs, and was SCCA Champ three times with DBs – and a fourth time with Ray Heppenstall driving his car.) I vintage raced a Matra DJet from ’99 thru ’01, and then a ’69 Alfa GTV for ’02 and ’03. The most interesting picture to me is in Part II: my dad is working on his new Rene Bonnet in the next pit stall, and what is obviously an engine/trans crate has been transported from the dock by the Bug in the foreground. (My dad is currently the oldest continuously-owned Volkswagen dealer in the U.S. – since 1951.) If I can share any info. with any of your authors or readers, I’ll be happy to do so!

Jim Hanna

Malvern, Pa.

jim@ybh.com