Before his second run for the LSR in 1964, Donald Campbell thought he had had it. But then, “I suddenly looked up and there was my father reflected in the windscreen as clearly as you are sitting there now…”

Why a story about the LSR Bluebirds in VeloceToday, one that has no Italian or French connections? Jonathan Sharp is our writer and our connection, as he not only has several Alfas but has a superb story to tell about the short and heroic life of Donald Campbell, including an exclusive story about the Campbell’s wallet, retrieved from his XKE right after the fatal accident in 1967 and never been on public display. A great story is a great story, whatever the country. Ed.

Story and Photos by Jonathan Sharp

Donald Campbell and the LSR

On Friday the 17th July 1964, after four years of struggle, Donald Campbell, CBE, finally broke John Cobb’s 1947 Land Speed record speed of 394.20 mph, driving his Bristol Proteus Gas Turbine powered Bluebird CN7. His friend Craig Breedlove had gone faster but his J47 Jet powered Spirit of America was considered by the governing body to be a tricycle, and more importantly, was not wheel driven so did not at the time meet the rules laid down.

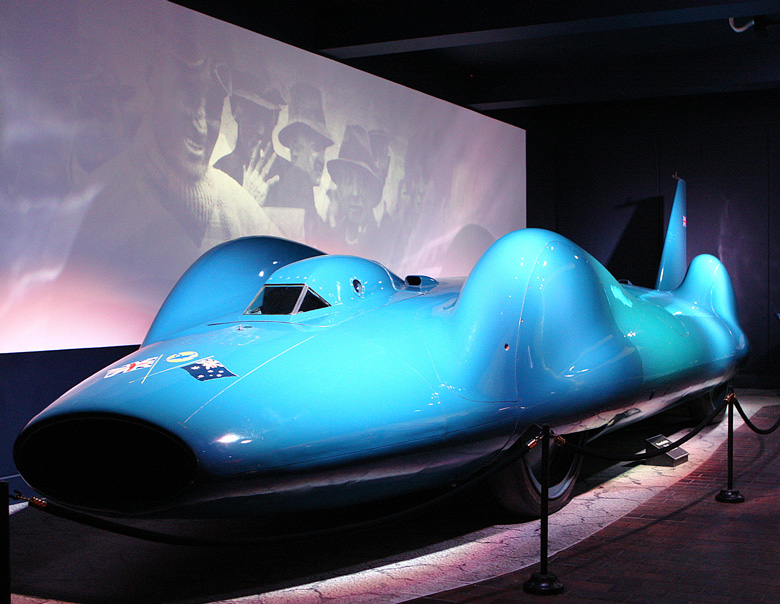

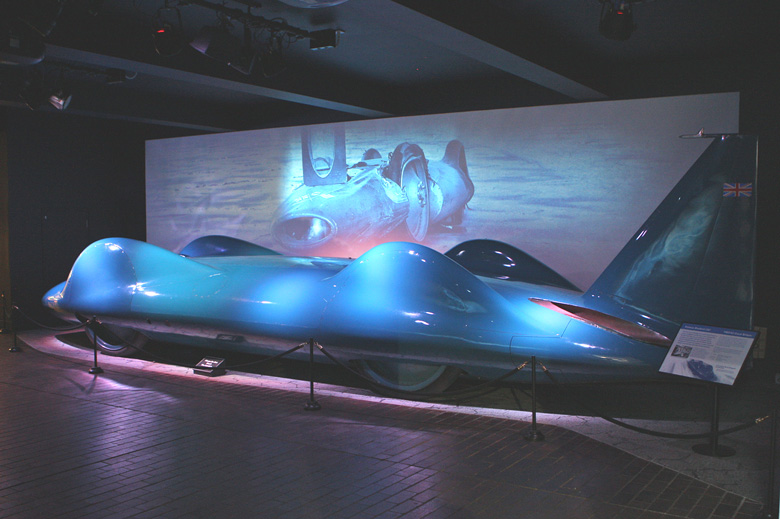

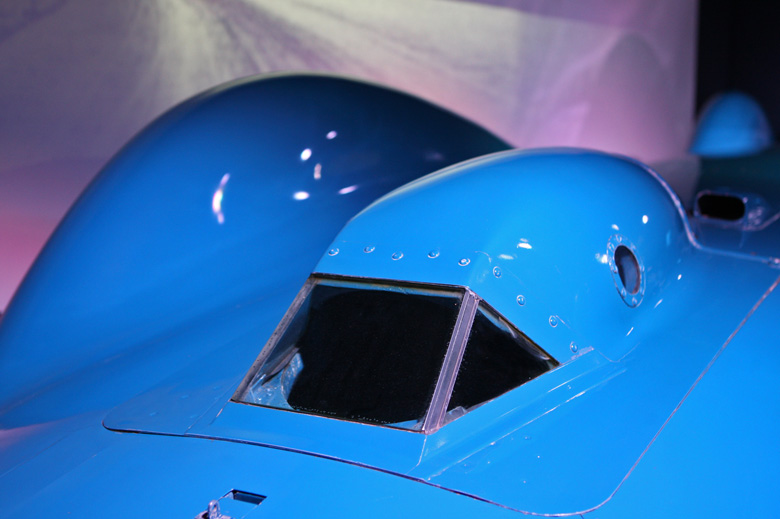

Donald, the son of speed King Sir Malcolm Campbell, had already broken the water speed record 6 times in his Jet powered Bluebird K7 hydroplane before deciding to switch his attention to breaking the Land Speed record. Bluebird CN7 was designed by brothers Lew and Ken Norris of Norris Brothers Ltd and approximately 50 British companies were involved in, or supported, the construction process. By September 1960 the car was ready so Donald and his team traveled out to the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah where trial runs duly commenced. On the 16th September at an estimated speed in excess of 300 mph Donald lost control. Bluebird flew for about 200 yards, then bounced three times before sliding to a halt. Considering the violence of the accident Donald sustained relatively minor injuries, the most serious being a fractured skull. Donald vowed to try again. On hearing this Sir Alfred Owen (BRM) offered to rebuild the car “…if Campbell has the guts to have another go I’ll build him a new car”. So strong was the construction of Bluebird that nearly 80% of the car was incorporated into the rebuilt car which now featured a tail fin and a more substantial metal and Perspex canopy.

When Leo Villa and Ken Norris finally made it to the scene of Donald’s crash they found the 4500 hp Bristol Proteus engine still purring away totally unaffected by the violence of the crash. CN7 had a designed top speed of between 475 and 500 mph. Power was sent to all four of the 52 inch wheels and tyres especially designed and built by Dunlop. The construction of the body of the car was like that of integral egg box.The internal framework of beams were constructed from an immensely strong yet light material which was formed from two sheets of high duty non corrosive alloy between which was sandwiched a light corrugated alloy foil similar to an honeycomb which was then Araldite bonded under high pressure. The accident scene is displayed behind the Bluebird at the National Motor Museum at Beaulieu.

In late 1962 the car was again ready. Donald had by then decided that a new course was required. BP, one of his backers then set about looking around the world for a new site. From their selection Donald choose Lake Eyre in South Australia, a vast dry salt pan in a very remote location approximately 700 kms north of Adelaide. It very rarely rains on Lake Eyre but when Donald turned up in 1963 the heavens opened. It happened again later in the year and again in 1964. Most of his backers had pulled out of the project by then, so Donald was mainly using his own money to fund the attempt. On the morning of the 17th July, 1964 the weather had improved but the course was still far perfect.

Here is the rev counter from Donald Campbell’s CN7 Bluebird Land Speed Record car. Note the MPH markings around the edge.

At 7.20 am Donald set off, his average speed through the measured mile was 403.10 mph. The team fueled up and checked the car and then changed the wheels. 38 minutes after coming to a halt the car was ready for the return run needed to secure the record. Leo Villa, Donald’s friend and mechanic happened to look over at the car and noted that Donald was sitting in the cockpit staring up at the windscreen, his face had suddenly lost all signs of the tension and strain which had built up over the previous four years. Leo then shouted from the booster truck “We are ready skipper…“ to which Donald answered “Fine” and a few moments later was on his way. The track by then was in a terrible condition, at mile three the track had already disintegrated during the first run and Bluebird’s wheels broke through the surface of the salt and were running in ruts up to four inches deep and filled with water. It was now or never. Donald powered on through with the rough salt shredding lumps of rubber from the tyres and the underside of the car running on the surface of the lake. Bluebird was taking a terrible pounding as she broke through the timing beam. Donald’s speed on the return run, identical 403.10 mph, he had finally done it, the record was his. (Donald also made an award winning film about the Australian records, called “How Long a Mile”.)

At the time of CN7s construction Smiths Instruments were working on the design for a head up display for use on forthcoming fighter aircraft. Such was the prestige of the project to the nation and the high level of backing and support offered to the project by British industry that it was decided to fit this new system to the cockpit of CN7. This would allow Donald to view his speed and acceleration on the windscreen rather than having to look down into the cockpit. Donald was a very superstitious man and he hated the colour green. The head up display was duly fitted and when Donald tried it out for the first time at the public presentation event at Goodwood he straight away order its immediate removal. Nobody had thought to ask Smith’s what colour the display on the windscreen was; it was green.

Donald Campbell and the WSR

Having previously suffered a stroke Sir Malcolm Campbell passed away at his home Little Gratton at 3 minutes to midnight on the 31st December 1948. In his book Into the Water Barrier Donald Campbell describes sitting at a great square flat topped desk in the book-lined study talking of little Gratton with Goldie Gardner, an old family friend, on a cold and windy day in March 1949. They were sipping whisky from the last bottle in the house and discussing Sir Malcolm, his memorial service and the upcoming auction of his effects. Goldie mentioned to Donald, “Have you heard what Henry Kaiser has just said?“

”No, what did he say ?“ asked Donald.

”That he is going to take the water speed record back to the States.” Goldie went on. ”Kaiser has built a speed boat with a twelve cylinder 3000 hp Allison engine. It’s an aluminium boat and it is said to have cost $150,000. Guy Lombardo is running it on the Potomac river, and he’s after the old man’s record.”

When Goldie had left Donald sat back in his father’s favorite arm chair and thought about Goldie’s final remark. “Suddenly I felt angry, the next moment I was thinking I’ll have a crack at improving the record myself. To hell with Kaiser. We’ll give him a run for his money” After the war, Sir Malcolm had converted Blue Bird K4, his second water speed record boat, to Jet power around a De Havilland Goblin engine. After lengthy discussions with Leo Villa Donald decided that as he believed that as they still retained the three Rolls Royce R Type engines, and as he wanted to go after the record as soon as possible, it would be best to have K4 converted back to R Type power. The work to convert K4 back to piston power was to be entrusted to Vospers.

That was when Donald first hit trouble which was to become a recurring theme. Sir Malcolm’s last will and testament had dictated that all of his estate was to be sold, with the money going into trust. Donald and his sister Jean were allowed to buy any items for the estate that they wished for a nominal fee. Donald chose to purchase the Blue Bird LSR Car and K4. The three R Type engines and the running gear that Sir Malcolm had used had been stored at Thompson and Taylor’s at Brooklands so Donald and Leo drove over to Brooklands to collect them only to be told by Ken Taylor that “…your father sold all that gear.”

“He – what?”

“He sold it all with the first Bluebird Boat (K3) about a year before he died. The whole lot was sold to a car dealer, I think he paid about £150.” Ken then gave Donald the dealers phone number. Mr Simpson, the dealer drove a hard bargain knowing that K4 was of no use without the gear so Donald was forced to buy the engine, propeller and V drive and K3 that Sir Malcolm had sold to him for £750 plus give him the Blue Bird record car.

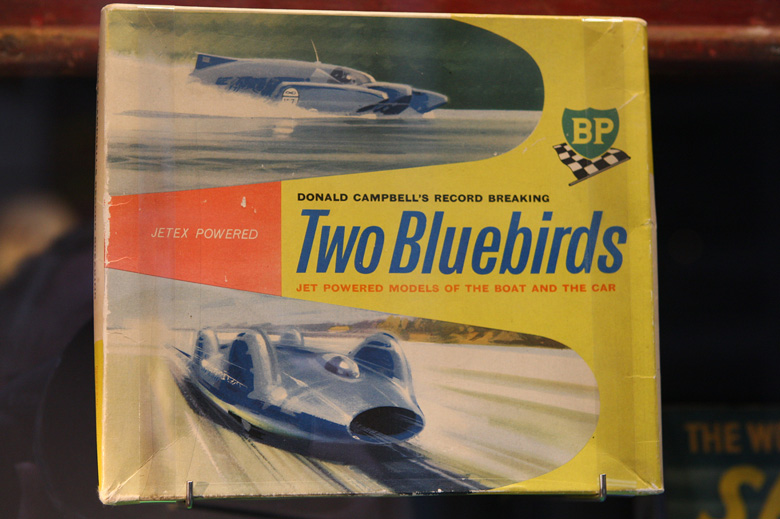

Health and safety were not an issue in 1960. To celebrate Donald Campbell’s Water Speed records and forthcoming Land Speed record exploits, British Petroleum offered this Bluebird CN7 Car and K7 Hydroplane Jetex micro rocket powered plastic model set as a promotional item that was available from BP petrol stations during 1960.

By the summer of 1949 Donald and his team had made it to Coniston Water and on the 19th of August Donald decided to go for the record. On his return run a small cap on the front of the gearbox came adrift spraying Donald with hot oil but he kept his foot down and finished the run. The team had just started to investigate the damage when the time keepers ran over and told them that he had broken his father’s record. Celebrations were to be short lived as half an hour later the time keepers had to admit that an error had been made and he had in fact missed the record by 2 mph. As the gearbox had almost seized up, the team decided that no further runs could be made and headed home to fix the boat before returning for another try. By June 1950 they were back at Coniston. It was whilst they were there that they learnt that the American Stanley Sayers’ boat Slo Mo Shun had pushed the record up to 160.32 mph. On the 7th August Donald took K4 out for a run. On his return leg at 145 mph he managed to cook the engine due to the water cooling scoop at the rear of the boat lifting clear of the water surface. The engineer Reid Railton, who had been in the States when Slo Mo Shun had broken the record, then arrived at Coniston where he told the team that Slo Mo Shun was a “prop rider” which uses the propeller as the third point of suspension. K4 was a three point hydroplane. The team then decided to return home and start work on having K4 converted to a prop rider. The work was carried out by the Norris Brothers and by September 1951 the team was back at Coniston. The now prop riding K4 was proving to be a much much faster, but then Donald’s bad luck struck again. At about 170 mph, and with the speed climbing ever faster there was an almighty crash, like a bomb going off, Bluebird began to bump and slide all over the place before finally coming to a halt thankfully right side up. She had hit a submerged log and was taking in water. She sank about 25 yards from the shoreline. She was recovered the following day but was too badly damaged to be repaired.

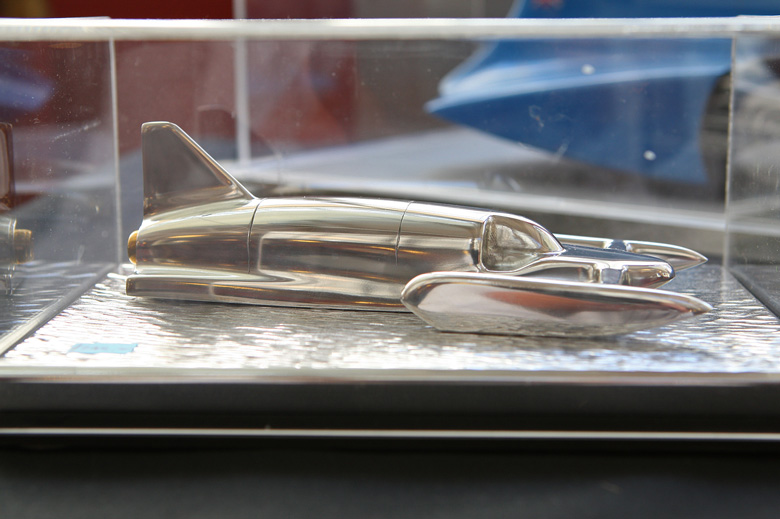

This is a model of Bluebird K7 in her final 1966/67 configuration. Her original power plant was the Metropolitan Vickers Beryl jet engine that had been fitted into the experimental Saunders Roe SRA 1 Jet flying boat, the fastest flying boat in the World. The Beryl produce 3750 lbs of thrust which had ultimately pushed Bluebird K7 up to 276 mph. To break the 300 mph barrier Donald decided that he would need more thrust so chose to fit Bluebird with the lighter and much more powerful 5000 lbs Thurst Bristol Siddeley Orpheus engine of a type fitted into the Fiat G91 and Folland Gnat aircraft. Donald managed to obtain a time expired Folland Gnat aircraft which in addition to providing the engine also provided the vertical tail fin.

Donald’s attention then turned to the design of K7, the jet powered Bluebird. With the K7, Campbell would break the Water Speed Record seven times, raising the record from 202.32 mph in 1955 to 260.35 mph in 1959.

On the 31st December 1964, late in the afternoon, Donald broke his own water speed record with a speed of 276.33 mph, also in Australia. He was therefore the only man ever to break both the land and water speed record in the same calendar year. His attention then turned to the construction of Bluebird CN8, a rocket powered car designed again by the Norris brothers with an estimated top speed of 850 plus mph.

But he wanted to make one more attempt to break his own water speed record. On the morning of the 4th January 1967, on Conistion Lake in England Donald’s luck finally ran out. At 08.51 am on his return run trying to push K7 past 300 mph. About 200 yards before the end of the measured kilometer, at a speed of about 328 mph Bluebird broke free of the water, completing a horrifying and yet gracefully 360 degree loop before plunging back into the lake. Donald died instantly.

*He was not the first nor the last to die attempting to break the Water Speed Record. See addendum below.

The story of Campbell’s Wallet

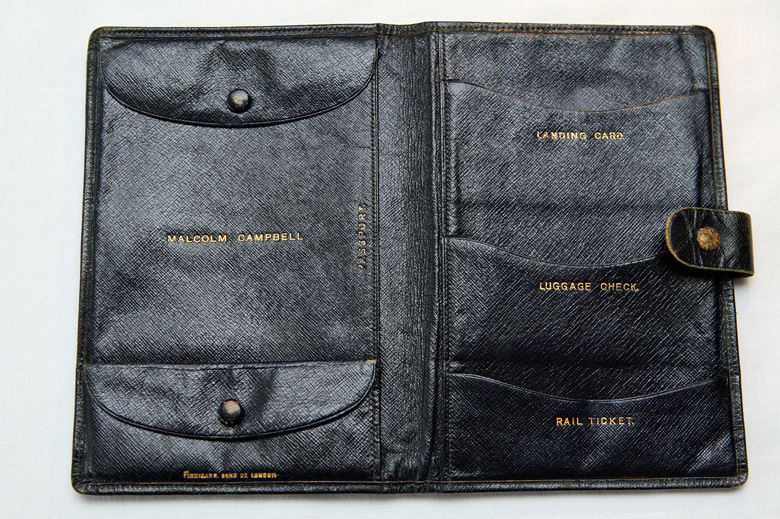

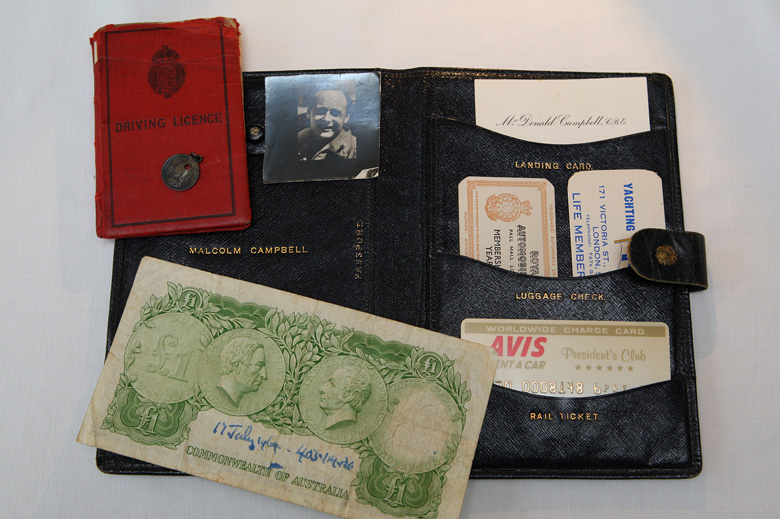

Campbell’s wallet originally belonged to Sir Malcolm. Considering how far this wallet has traveled whether it be on board the Cunard liner Berengaria with Sir Malcolm, or on board the SS United States, or a Boeing 707 with Donald it hardly shows any sign of wear.

Dating from the golden age of ocean liner travel this travel wallet was made by Finnigans of Bond Street London for Donald’s father Captain (later Sir) Malcolm Campbell during the 1930s. Upon Sir Malcolm’s death the wallet was used by Donald. Donald had left the wallet in the glove box of his E Type Jaguar before setting out on his final run. Since that time, the wallet has been in private hands and never before seen by the public.

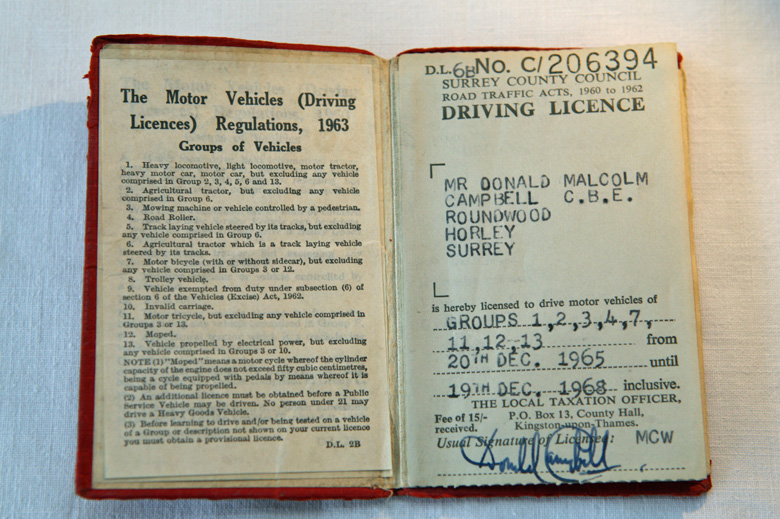

Campbell’s driving licence. He had recently moved from Roundwood to Priors Ford in Leatherhead but presumably would have waited until the licence needed renewing in December 1968 before changing the address.

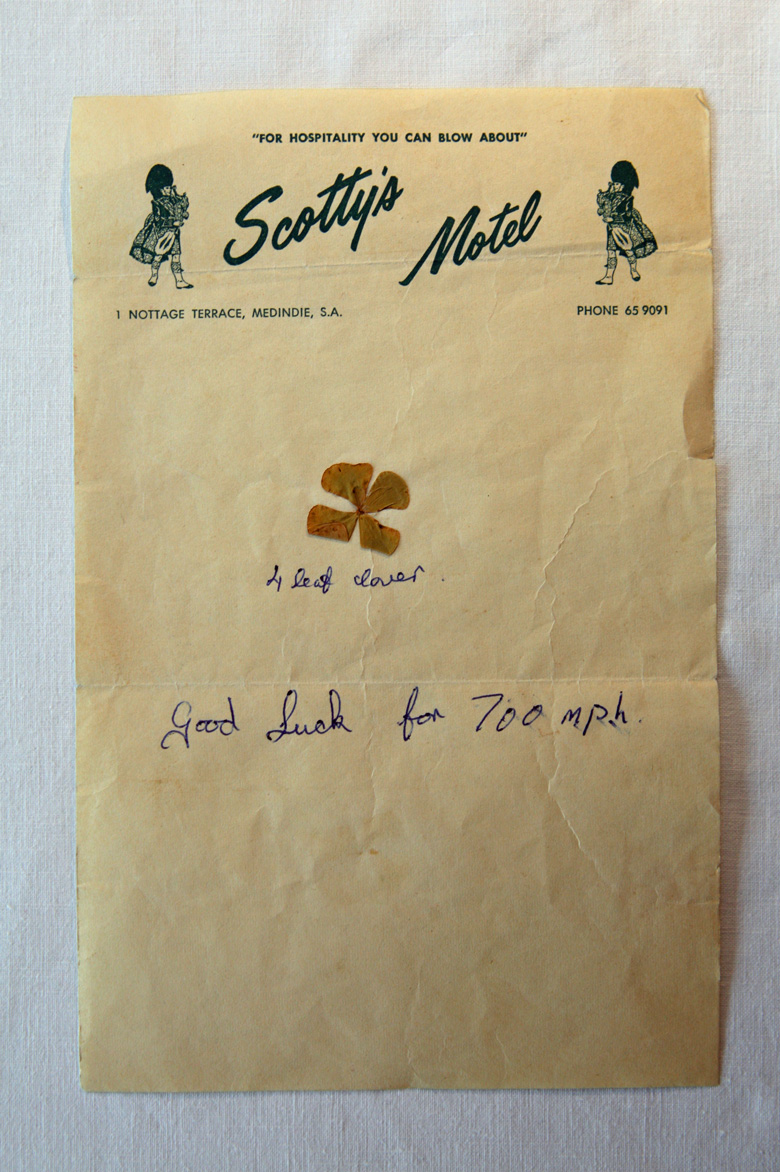

A good luck note from the motel Campbell was staying at during the time of his final Land Speed Record attempt in Australia.

The wallet contained Donald’s driving licence, RAC club membership card, His business card, Royal Yacht Association card, A plastic Avis Presidents club card which he had yet to sign, a lucky penny, a note with a four leaf clover attached to it from the owner of Scotty’s Motel wishing Donald good luck in his quest for 700 mph, and an Australian £1 note on which Donald has written 17th July 1964 403.10 mph.

It will be alright, boy

Always influenced by his great father, Donald no doubt had him in mind when attempting the LSR in 1964. Builder Ken Norris recalled that in the evening whilst the celebration party was going on around them he asked Donald what had happened in the cockpit before he started his return run through the rutted salt. Donald replied “I nearly killed myself. I was so near going out of control it wasn’t even funny, and when I was sitting in the cockpit at the end of the run I really thought I had had it. For I knew the second run would be worse. I saw no hope at all. I suddenly looked up and there was my father reflected in the windscreen as clearly as you are sitting there now. I even recognized the white shirt and flannels he used to wear. For a few seconds he looked at me, smiling. Then he said, ‘Well boy. Now you know how I felt that time in Utah when the wheel caught fire in 1935. But don’t worry’, he added, ‘It will be all right boy.’”

Malcolm’s Legacy

By the early 1930s the British speed kings of Sir Henry Segrave and Sir Malcolm Campbell had become hugely famous. Each new record speed being commemorated, with the speed king’s being granted Knighthoods, and various items being produced for the public to buy. Here is a tea service produced by Paragon China to celebrate Sir Malcolm Campbell’s 1932 record of 253.97 mph in Blue Bird.

In 1910 Malcolm Campbell began racing cars at Brooklands. He christened his car Blue Bird, painting it blue, after seeing the play The Blue Bird by Maurice Maeterlinck at the Haymarket Theatre. Note that Malcolm called his cars Blue Bird, while Donald used Bluebird.

Malcolm Campbell’s 350 hp Blue Bird at the 2016 Festival of Speed. The Blue Bird is normally displayed at Beaulieu. Malcolm broke the land speed record for the first time in 1924 at 146.16 mph (235.22 km/h) at Pendine Sands near Carmarthen Bay in a 350HP V12 Sunbeam; Campbell broke nine land speed records between 1924 and 1935, with three at Pendine Sands and five at Daytona Beach.

Blue Bird made its first record runs back on Daytona Beach in early 1935. On 7 March 1935 Campbell improved his record to 276.82 miles per hour (445.50 km/h) but this led to the Bonneville Salt Flats of Utah. This time the young Donald Campbell accompanied his father. On 3 September 1935, the 300 mph barrier fell by a bare mile-per-hour, that being 484,955 km, crowning Sir Malcolm Campbell’s record-breaking career on land.

I took this shot of Tonia Campbell Berne and Don Whales at Brooklands on the 17th July 2014 at a small celebration on the 50th anniversary of Donald breaking the land speed record. Tonia was Donald’s third wife and widow. During the Australian adventures with the car and boat she was known by the team as Fred. Don Wales is the grandson of Sir Malcolm and a record breaker to boot being the driver of “Inspiration” the British Steam record car, He is also the holder of the Guinness world record for a ride on lawn mower having clocked up an average speed over the measured mile of 87.833 mph on Pendine sands, a place his Grandfather knew well, having broken the Land Speed record there three times during the 1920s. The car between them is Donald’s Aston Martin.

*The Deadly Chase for the World Speed Record Addendum from Wiki

On 13 June 1930 Sir Henry Segrave piloted Miss England II to a new record of 158.94 km/h (98.8 mph) average speed during two runs on Windermere, in Britain’s Lake District. Having set the record, Segrave set off on a third run to try to improve the record further. Unfortunately during the run, the boat struck an object in the water and capsized, with both Segrave and his co-driver receiving fatal injuries.

John Cobb, was hoping to reach 320 km/h (200 mph) in his jet-powered Crusader. A radical design, the Crusader reversed the ‘three-pointer’ design, placing the floats at the rear of the hull. On 29 September 1952 Cobb tried to beat the world record on Loch Ness but, while travelling at an estimated speed of 338 km/h (210 mph), Crusader’s front plane collapsed and the craft instantly disintegrated. Cobb was retrieved from the water but had already died of shock.

Two years later, on 8 October 1954, another man would die trying for the record. Italian textile magnates Mario Verga and Francesco Vitetta, responding to a prize offer of 5 million lire from the Italian Motorboat Federation to any Italian who broke the world record, built a sleek piston-engined hydroplane to claim the record. Named Laura III, after Verga’s daughter, the boat was fast but unstable. Travelling across Lake Iseo, in Northern Italy, at close to 306 km/h (190 mph), Verga lost control of Laura III, and was thrown out into the water when the boat somersaulted. Like Cobb, he died of shock.

Until 20 November 1977 every official water speed record had been set by an American, Canadian, Irishman or Briton. That day Australian Ken Warby broke the Anglo-American domination when he piloted his Spirit of Australia to 464.46 km/h (288.60 mph)[7] to beat Lee Taylor’s record. Warby, who had built the craft in his back yard, used the publicity to find sponsorship to pay for improvements to the Spirit. On 8 October 1978 Warby travelled to Blowering Dam, Australia, and broke both the 480 km/h (300 mph) and 500 km/h barriers with an average speed of 511.12 km/h (317.6 mph). As he exited the course his peak speed as measured on a radar gun was approximately 552 km/h (345 mph).

Warby’s record still stands as of 14 February 2015. There have only been two official attempts to break it, both resulting in the death of the driver.[10]

Lee Taylor tried to get the record back in 1980. Inspired by the land speed record cars Blue Flame and Budweiser Rocket, Taylor built a rocket-powered boat, Discovery II. The 40-foot (12 m) long craft was a reverse three-point design, similar to John Cobb’s Crusader, albeit of much greater length.

Originally Taylor tested the boat on Walker Lake in Nevada but his backers demanded a more accessible location, so Taylor switched to Lake Tahoe. An attempt was set for 13 November 1980, but when conditions on the lake proved unfavourable, Taylor decided against trying for the record. Not wanting to disappoint the assembled spectators and media, he decided to do a test run instead. At 432 km/h (270 mph) Discovery II started to become unstable. It has been speculated that it may have hit a swell. Whatever the cause, the boat’s unstable lateral oscillations caused the left float to collapse, sending the boat plunging into the water. The cockpit section with Taylor’s body was recovered three days later. The cockpit had not floated as intended and Taylor drowned as a result.

In 1989 Craig Arfons, nephew of famed record breaker Art Arfons, tried for the record in his all-composite fiberglass/Kevlar Rain X Challenger, but died when the hydroplane somersaulted at 483 km/h (301.875 mph).

There’s an excellent book with many rarely seen photographs, “Donald Campbell, Bluebird and the Final Record Attempt” by Neil Sheppard, which covers his attempts for the Water Speed Record.

After Campbell was killed the British rock group Marmillion released “Out of this World” on their album “Afraid of Sunlight.” The almost eight minute track was about Campbell and his final attempt and death at Coniston Water.

Thanks for the details on Little Gatton (not Gratton)?

Thank you for a another wonderful VT article….I’ve always been fascinated by the Campbell’s pursuit of the LSR and WSR and was at Beaulieu when they ahd the “For Britain and For The Hell of It” display. I know that Tonia had spent some time in Palm Springs as few years ago. For the Blackhawk Museum’s Speaker Series we’d welcome the opportunity to have a Campbell member talk about the life & times of both Donald and Malcolm Campbell if anyone can connect us with them.

Good to hear from you! There are also some chilling videos of Campbell’s fatal accident on youtube, but we’ll let the readers search at will.

One of the wheels from the Bluebird is on the wall of Duttons Garage , a classic and and luxury car dealer in Melbourne Australia , they run a video on an old TV of his time in Australia

Hi Pete:

Good story on Donald Campbell. I should mention that a Canadian, Art Asbury held the world record for exploits on water for a time, a very short time, like a week in the unlimited hydroplane Miss Supertest II. Apparently, she was a dangerous craft, very unstable at speed. Art cautioned his friend Bob Hayward (By the way three times Harmsworth Trophy winner in unlimited hydroplane racing) that he had better be careful running her in a race on the Detroit river. “That bitch will kill you,’ he warned. Bob went out in Miss Supertest II and did indeed kill himself when she barrel rolled – I think during qualifying. Bob had raced Miss Supertest III to various victories but for some reason, Miss Supertest III was unavailable. I met Bob a couple of times as he was my father’s bowling buddy.

Hi, Little Gatton near Reigate is close to where I had my stable house in which Richard I’Anson rebuilt my “Lyon” Bugatti. Sir Malcolm died at Little Gatton House on New Year’s Eve 1948. Years later, when the balance of his household effects were auctioned, I purchased a collection of horse brasses and hand coloured prints, and in fact still have them here in California, but minus my inglenook fireplace around which to display them. Thus they are in storage, waiting to go to a suitable timbered and thatched cottage. All the best. Peter Giddings. P.S. Blue Birds, the story of the Campbell dynasty by Gina Campbell is a fair read. Peter Giddings